“It will profoundly change the Senate.” “It will benefit media-savvy members, forcing the retirement of those uncomfortable with new technology.” Such concerns were commonly heard in the 1980s, as the Senate debated bringing television cameras into its Chamber. They also echoed complaints heard 60 years earlier, when the new medium was radio and the question was, “Should Congress go on the air?”

World War I produced significant advances in radio technology, and by 1920 radio pioneers were exploring its entertainment and public service potential. In 1924 Senator Robert B. Howell of Nebraska, a former chairman of a national radio commission, became the first to formally propose that the Senate broadcast its proceedings. A few years later, North Dakota’s Gerald Nye called for a 50,000-watt “superpower station” on Capitol Hill to produce an audible Congressional Record. When research indicated that a whopping $3.3 million would be needed to implement such a plan, the proposal died, but it wasn’t just sticker-shock that killed the idea.

As the Senate considered radio coverage, many wondered if senators would have an audience. Some debates “arouse as much public interest as a championship prize fight,” commented a skeptic in 1927, but no one “wants to listen to the monotonous dronings that make up the typical legislative day.” Others argued that the Senate just wasn’t ready to take such a bold step into the modern world. “The chief drawback here is the attitude of the Senate itself,” explained a New York Times reporter in 1929. “Most of its members are . . . constitutionally opposed to the idea of broadcasting its proceedings.”1

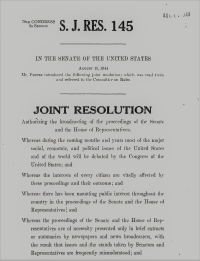

The idea surfaced again in 1944, following the successful radio broadcasts of the Democratic and Republican Party conventions. On August 15, Florida senator Claude Pepper introduced a joint resolution calling for radio coverage of congressional debate. If the people of the country “could by the marvel of the radio . . . be witnesses of the deliberations of their Representatives and Senators in Congress,” Pepper said, “I believe it would be in furtherance of the democratic process.” Two weeks later, Representative John Coffee of Washington introduced a nearly identical bill in the House of Representatives. In Pepper's efforts to advance his joint resolution, he challenged his colleagues to consider the optics of not moving forward with the times. "If we don't broadcast the proceeding some time and keep step with the advance of radio," he argued, "the people are going to begin asking whether we are afraid to let them hear what we are saying. It's their business we are transacting." Nevertheless, Pepper's and Coffee's efforts also failed. "The idea of putting Congress on the air might appeal to many a U.S. citizen," Time magazine declared, "but to most Congressmen the idea is nightmarish."2

Finally, in 1945, Congress hit the airwaves with Congress on the Air, a weekly program broadcast at 8:00 p.m. on Sundays. Competing against the popular Fred Allen Show and the mystery series Crime Doctor, the half-hour program featured members of Congress discussing major issues of the day, such as the October 9 debate between New Mexico senator Carl Hatch and Alexander Wiley of Wisconsin on the proliferation of atomic weapons. A modest success, this program fell far short of gavel-to-gavel coverage of Senate action but did lead to other suggestions. “Congress in Action,” for example, was a proposal to air Senate floor debates every Wednesday. Such programming could be very popular, argued proponents, allowing constituents to listen to congressional sessions the way they did baseball games, Frank Sinatra’s voice, or Jack Benny’s jokes. But radio-shy members wondered, who would decide the topic of debate, and how would they avoid just putting on a show for the listening public?3

Although the proponents of radio failed in their attempts to broadcast floor proceedings, they had more success with committee action. Radio microphones became a familiar sight in congressional hearings by the 1940s as resistance to radio coverage diminished, but the change in attitude came too late. By then, a new phenomenon had captured the American imagination, and discussions of radio broadcasts from Capitol Hill soon fell victim to the excitement over television.

"A new synthesis of legislative process and mass media is in the making and seems only to wait upon the appropriate catalyst," political scientist Ralph M. Goldman predicted in 1950, "for the elements to be combined are many and the inertia to be overcome is great." Indeed, change did eventually make its way into the Senate Chamber. “Today we catch up with the 20th century,” Majority Leader Robert Dole told the C-SPAN audience on June 2, 1986, as Senate television coverage began. “No longer will the great debates in this Chamber be lost forever.” No doubt, that’s exactly what Nebraska’s Robert B. Howell had in mind—way back in 1924.4

Notes