Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the historic records of Senate committees highlighted in this month's “Senate Stories.”

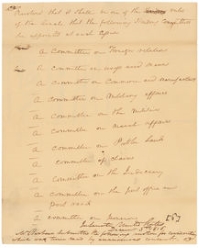

In December 1816, the Senate established its first permanent standing committees. Prior to that time, the Senate had relied on ad hoc or temporary committees to sift and refine legislative proposals, to consider nominations and treaties, and to fulfill other constitutionally designated rights and responsibilities. The demands of a growing nation and a war with Great Britain prompted the Senate to revise its procedures. On December 10, 1816, senators approved a resolution to establish 11 permanent standing committees with jurisdictions over designated areas such as finance, foreign relations, military affairs, commerce, and the judiciary.

The records of these early ad hoc and standing committees, and all subsequent committees, represent the majority of official Senate records preserved and housed at the Center for Legislative Archives at the National Archives and Records Administration. This large collection of archived Senate committee records offers ample evidence of the important work done by each committee.

The Center for Legislative Archives preserves the oldest and most historically significant congressional records in its Treasure Vault, including records created during the First Congress, which convened in 1789. Along with the first Senate Journals, there are bills, war and censure resolutions, petitions, presidential messages, nominations, and proposed constitutional amendments. The simple, handwritten 1816 resolution creating the standing committees is among these precious documents. The fact that these documents were gathered and preserved long before the creation of the federal archives system makes their survival all the more extraordinary.

The following Senate documents from the Treasure Vault highlight the work of three of the Senate's original standing committees: Pensions, Commerce and Manufactures, and Judiciary. Each document captures a moment in time while providing a window into the operation of Senate committees as constitutional government-in-action.

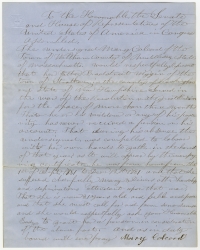

Petition from Mary Colcord, 32nd Congress (1852)

In 1818 Congress passed a pension bill to provide financial support to Revolutionary War veterans. The oversight of this support (sometimes the only form of income for veterans and their families) was managed by the Committee on Pensions, one of the standing committees created in 1816. The committee’s archival records include applications like this one submitted to the Senate in 1852 by 81-year-old Mary Colcord. To document the service of her father, Bradstreet Wiggin, during the Revolutionary War, Colcord submitted the handwritten diary of Samuel Leavitt, a contemporary of her father from the same New Hampshire town who had served in the same company. The diary records Leavitt's service in the New Hampshire militia in 1780. It was given to the committee by Colcord presumably as evidence of her father's service, although she indicates that her father served during a different year. Consequently, the Senate’s archival collection has been enriched by this rare and historic record detailing a common soldier’s experience during the Revolutionary War. Although Colcord's claim, submitted more than 70 years after the war ended, was ultimately rejected by the committee, Congress did continue to pay Revolutionary War pensions as late as 1906.1

Following a congressional reorganization in 1946, the Senate moved the management of all war pensions to the Committee on Finance. In 1970 the Senate formed a Committee on Veterans Affairs and consolidated the oversight of all veterans’ issues, including pensions, under the jurisdiction of the new committee.

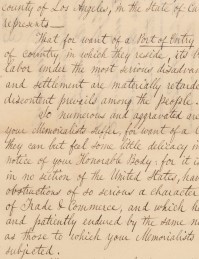

Memorial of Inhabitants of Los Angeles County, California, praying for establishment of a port of entry in that county, 31st Congress (1850)

The importance of commerce in national affairs led to creation of the Committee on Commerce and Manufactures in 1816. Regulating commerce is an expressed congressional responsibility, so it is not surprising to find among the committee’s papers this memorial, a form of petition, of the residents of Los Angeles County, California, part of the newly acquired Mexican Cession region, asking for the establishment of a port of entry in that county. This document, dated July 1850, was referred to the Commerce Committee amidst the debate over the Compromise of 1850, which resulted in establishing statehood for California that same year. Rapid progress in technology, communication, and commercial development in the 19th and 20th centuries prompted the Commerce Committee to split into various smaller committees to handle an ever-expanding legislative and oversight caseload. Two legislative reorganizations, in the 1940s and 1970s, consolidated most of these committees under the jurisdiction of today’s Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

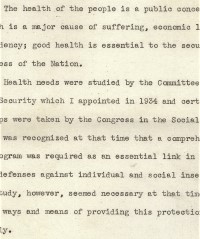

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s message regarding national health, 76th Congress (1939)

On January 23, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a four-page presidential message to Congress calling for the creation of a “national health program … to make available in all parts of our country and for all groups of our people the scientific knowledge and skill at our command to prevent and care for sickness and disability.” Presidential messages, including the annual State of the Union Address, serve as vehicles for the president to raise urgent matters with Congress. The subjects of public health and health care assistance reflect the expansion of the role of the federal government in response to the national crisis of the Great Depression. Perhaps because of the references to science and economic loss, as well as the interstate nature of the proposed program, the message was referred to the Committee on Commerce.

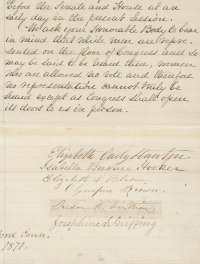

Petition from Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and others, 42nd Congress (1871)

The First Amendment grants individuals the right to petition Congress to redress grievances or to seek the assistance of the government. Petitions allow ordinary citizens to express their views to their elected representatives. Managing these petitions became the responsibility of Senate committees, including the Judiciary Committee, which was established as a permanent committee in 1816 to oversee the courts, judicial proceedings, and constitutional matters. This petition is typical of thousands received by the committee supporting woman suffrage. It is particularly noteworthy because it includes the signatures of leading suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony who ask that they “be permitted in person, and on behalf of the thousands of other women who are petitioning Congress … to be heard … before the Senate and House.” Suffragists first testified before a Senate committee in 1878 and continued to do so until the Senate passed the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919, which granted female suffrage upon ratification in 1920.

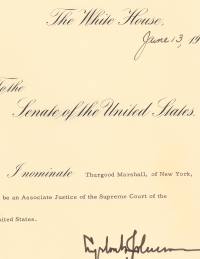

President Lyndon B. Johnson's nomination of Thurgood Marshall to be associate justice of the Supreme Court, 90th Congress (1967)

The Senate has the constitutional power to advise and consent on presidential nominations, and Senate committees play an important role in that process. Before the 1860s, the Senate considered most nominations without referring them to a committee for review or investigation, although the Judiciary Committee did consider some nominees as early as the 1830s. In 1868 the Senate adopted rules to provide for more routine referral of nominations to "appropriate committees," but investigations of judicial nominees were rare. By the early 20th century, the Judiciary Committee had become much more integral to the nomination process, and by the mid-to-late 20th century, nominees were regularly testifying before the committee. This featured record of the Judiciary Committee, President Lyndon B. Johnson's 1967 nomination of Thurgood Marshall to be an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, documents the historic appointment of the first African American Supreme Court justice.

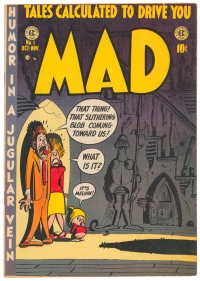

First Issue of MAD magazine, from the investigative files of the Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, 82nd Congress (1952)

The creation of standing committees enabled the Senate to better pursue its implied constitutional powers of oversight and investigation to inform legislation or to bring attention to important matters. Since World War II, congressional investigations into allegations of wrongdoing, fiscal mismanagement, national security, corporate malpractice, and social and economic issues of concern have resulted in better legislation, taxpayer savings, consumer protections, and stronger ethics laws. In most cases, standing committees serve as the Senate's principal investigative arm, but the Senate also has entrusted this responsibility to special and select committees.

The broad and extensive nature of these investigations has created an archival record that includes an interesting and unusual assortment of documents and artifacts. Among these is a collection of early 1950s comic books and youth publications, including 12 of the first 13 issues of MAD magazine. Popular films like Nicholas Ray’s 1955 Rebel Without a Cause dramatized public concern about wayward youths and juvenile violence, prompting a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee to launch an inquiry. That investigation explored the role of popular culture, including publications like MAD magazine, in shaping adolescent behaviors and attitudes. The subcommittee continued to investigate the issue of juvenile delinquency for many years.

Illinois senator Everett M. Dirksen once remarked that “floor debate on a bill can be likened to an iceberg…the top shows, but the major part is underneath. The work of the committee is the large part that is not seen by the public.”2 The archived records of Senate committees reflect the behind-the-scenes work of senators and staff. They demonstrate the routine, the historical, the touchingly personal, and even the whimsical nature of committee work. Through these records we gain a better understanding of the history of the Senate and the ever-evolving work of Congress.

Notes