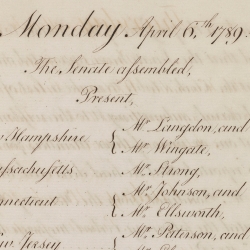

| 202404 6Treasures from the Senate Archives: The Long Journey to Quorum

April 6, 2024

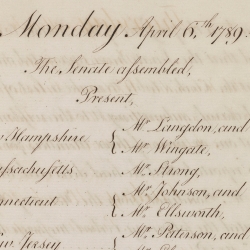

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress. This year’s collection of treasures from the Senate Archives along with correspondence from manuscript collections tells the story of this very event—the Senate’s long journey to a quorum in the late winter and early spring of 1789.

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress. This year’s collection of treasures from the Senate Archives along with correspondence from manuscript collections tells the story of this very event—the Senate’s long journey to a quorum in the late winter and early spring of 1789.

The Framers of the Constitution included a formula for its ratification. As stated in Article VII: “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution.” When the necessary ninth state—New Hampshire—ratified the Constitution on June 21, 1788, the Congress under the Articles of Confederation began the transition to form a new federal government. On September 13, that soon-to-expire Confederation Congress issued an ordinance giving states authority to elect their first senators and set the convening date for the First Federal Congress—March 4, 1789. As it turned out, that was the easy part.1

When the convening date arrived, the First Congress was to meet in the newly refurbished and renamed Federal Hall in New York City to count the electoral votes for president and vice president, inaugurate the winners, and proceed with its business. Writing to his wife that momentous day, Pennsylvania senator Robert Morris described the dramatic transition taking place in the city: “Last Night they fired 13 Canon [sic] from the Battery here over the Funeral of the Confederation & this Morning they Saluted the New Government with Eleven Cannon being one for each of the States that have adopted the Constitution,” he wrote. (Rhode Island and North Carolina had not yet ratified the Constitution.) “[R]inging of Bells & Crowds of People at the Meeting of Congress gave the air of a grand Festival to the 4th of March 1789 which no doubt will hereafter be Celebrated as a New Era in the Annals of the World.” The New York Daily Advertiser reported that “a general joy pervaded the whole city on this great, important and memorable event; every countenance testified a hope that under the auspices of the new government, commerce would again thrive … and peace and prosperity adorn our land.”2

The exultation soon transitioned to disappointment, however, when both houses fell short of reaching the quorum required by the Constitution to conduct their business (30 representatives and 12 senators). Only 13 of the 59 representatives and only 8 of the 22 senators from the 11 states were present to offer their credentials (certificates of election) and be sworn in. "The number not being sufficient to constitute a quorum, they adjourned," reads the first entry in the Senate Journal.3

“We are in hopes these Numbers will Appear tomorrow,” an optimistic Morris wrote. News reports were likewise hopeful. “It is expected that a sufficient number to form a quorum will arrive this evening. Should that be the case the votes for President and Vice-President will be counted to-morrow,” the New York correspondent to the Massachusetts Centinel explained. In the subsequent days, the ongoing delay diminished such confident expectations and tested the patience of an anticipative country, including the punctual group of eight senators. Day after day, these senators appeared in the Senate Chamber only to be disappointed, harboring growing concerns of the government’s inability to operate.4

The image of a government paralyzed by absenteeism was all too familiar. The Confederation Congress had encountered similar problems, and in its final months, that legislature remained practically powerless to conduct business due to a lack of quorum. Thus, when only eight of the senators elected to the new federal government under the Constitution presented themselves on March 4, many feared a continuation of the old difficulty. "The members of the First Federal Congress who were on hand in New York on the appointed first day of the session were anxious to avoid any image of impotence caused by the lack of a quorum,” one historian explained. “They hoped that the new government could begin its work promptly, conveying an impression of the seriousness of their attention to duty to the expectant public." When a quorum failed to materialize over the next few days, those who had arrived pleaded with their missing colleagues in a letter. "We apprehend,” they wrote, “that no arguments are necessary to evince to you the indispensable necessity of putting the Government into immediate operation; and, therefore earnestly request, that you will be so obliging as to attend as soon as possible."5

Frustration and resentment grew as another week passed, and another, and still no quorum. “We earnestly request your immediate attendance,” they implored the absentees on March 18. Pennsylvania senator William Maclay complained in a letter to his friend Benjamin Rush, “I have never felt greater Mortification in my life[;] to be so long here with the Eyes of all the World on Us & to do nothing, is terrible.” In a later letter he added, “It is greatly to be lamented, That Men should pay so little regard to the important appointments that have devolved on them.” Members of the House of Representatives were likewise discouraged. “I am inclined to believe that the languor of the old Confederation is transfused into the members of the new Congress,” Massachusetts representative Fisher Ames wrote. “We lose credit, spirit, every thing. The public will forget the government before it is born.”6

The senators grew hopeful when Senator William Paterson of New Jersey appeared on March 19, followed soon thereafter by Richard Bassett of Delaware on the 21st and Jonathan Elmer of New Jersey on the 28th. Now 11 strong, they were still one man short of a quorum. Bassett earnestly wrote to his absent colleague, Delaware senator George Read, expressing concern that the House would reach a quorum before the Senate:

Where the Twelfth Member is to come from is not yet known, unless you can be prevailed on to Move forward—The Members of the Senate are very uneasy, and press me Exceedingly to urge the Necessity of your Making all Possible Dispatch in coming forward, as it is apprehended next week will bring forward a Sufficient Number of the other Branch to proceed, and they wish not to have the fault lain at our Door.7

Charles Thomson, who had been the secretary of the Continental Congress and was serving in a similar capacity during this interim period, also made a plea to Read, writing that he was “extremely mortified” that Read had not traveled to New York with Bassett, and expressing his fears that the delay would fuel opposition to the new government:

Those who feel for the honor and are solicitous for the happiness of this country are pained to the heart at the dilatory attendance of the members appointed to form the two houses while those who are averse to the new constitution and those who are unfriendly to the liberty & consequently to the happiness and prosperity of this country, exult at our languor & inattention to public concerns & flatter themselves that we shall continue as we have been for some time past the scoff of our enemies.…What must the world think of us?8

Despite the frustrations, blame, and admonishment, there were some well-founded and justifiable reasons for the delayed arrival of members, the most significant of these being the challenges of wintertime travel in the 18th century. The trip from Boston to New York City typically took six days, but during the winter, that journey could take two weeks or more. Senators navigated treacherous roads in wagons or sleighs and often were forced to seek refuge at nearby farms when conditions grew too dangerous. “There was no possibility of conveying [us] in February to new-york, by water or on wheels,” complained Massachusetts representative Elbridge Gerry. Senators from Maryland or Virginia endured weeks-long travel on horseback or in rickety coaches, braving cold and icy waters at five separate ferry crossings. Southerners, traveling mostly by sea, faced the greatest hazards of all. One southern member was delayed for weeks when his ship foundered off the Delaware coast.9

In addition to arduous weather and travel conditions, there were personal and political reasons for the delayed arrival of members of the new Congress. George Read, who finally arrived on April 13, was likely delayed due to sickness, as he later wrote that he had been unwell during this time. Correspondence from this period reveals that several others were delayed by illness, including Senator Elmer and Massachusetts senator Tristram Dalton. Politics also played a role. New York’s state legislature was deadlocked over candidates for months and did not send senators to Federal Hall until July 1789.10

On April 1, the attending senators’ fears were realized when the House became the first of the two chambers to achieve a quorum. Five days later, on April 6, the necessary 12th senator finally arrived, Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee. The Senate then turned to the important business of helping to formalize the new national government by declaring the winner of its first presidential election. “Being a Quorum, consisting of a majority of the whole number of Senators of the United States. The Credentials of the afore mentioned members were read and ordered to be filed,” the Senate Journal reads. “The Senate proceeded by ballot to the choice of a President [pro tempore], for the sole purpose of opening and counting the votes for President of the United States.”11

Thankfully, the inauspicious beginning of the First Congress’s first session would not be repeated, as subsequent sessions saw some improvement in punctuality. In January 1790, at the start of the second session, a more experienced Senate reduced its convening delay to only two days. Finally, at the beginning of the third session in December 1790, the necessary quorum appeared on time and the Senate got down to business as planned. With the new government firmly established and transportation and infrastructure gradually improving, summoning a quorum would prove less of a challenge for future Congresses.

Notes

1. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904–37), 34:523, September 13, 1788.

2. Robert Morris to Mary Morris, March 4, 1789, and New York Daily Advertiser, March 5, 1789, included in Charlene Bangs Bickford et al., eds., Correspondence: First Session, March–May 1789, vol. 15 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 15–16.

3. Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., March 4, 1789.

4. Robert Morris to Mary Morris, March 4, 1789, and Massachusetts Centinel, March 14, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:15–17.

5. Charlene Bangs Bickford, “‘Public Attention Is Very Much Fixed on the Proceedings of the New Congress’: The First Federal Congress Organizes Itself,” in Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1999), 139; Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, March 11, 1789. Various Papers 1789–1982, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

6. Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, March 18, 1789. Various Papers 1789–1982, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; William Maclay to Benjamin Rush, March 19, 1789 and March 26, 1789, and Fisher Ames to George R. Minot, March 25, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:78, 126, 134.

7. Richard Bassett to George Read, March 21, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:86.

8. Charles Thomson to George Read, March 21, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:90–91.

9. A good description of the hazards of travel to New York at this time is included Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:19–22; Elbridge Gerry to James Warren, March 22, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:92.

10. William Thompson Read, Life and Correspondence of George Read: A Signer of the Declaration of Independence, with Notices of Some of His Contemporaries (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Company, 1870) 473; "New York’s First Senators: Late to Their Own Party," National Archives' Pieces of History blog, accessed March 26, 2024, https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2014/07/26/new-yorks-first-senators-late-to-their-own-party/.

11. Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., April 6, 1789.

|

| 202401 31The Evolution of the Response to the State of the Union

January 31, 2024

Each year, before a joint session of Congress, the president fulfills his or her constitutional duty to "from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient." Today’s State of the Union Address follows well established protocols and rituals, but one aspect in particular—the opposition response—is a modern practice that has evolved to address a problem faced by Congress in its earliest years.

Each year, before a joint session of Congress, the president fulfills his or her constitutional duty to "from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient." The ceremony that we know today as the State of the Union Address follows well established protocols and rituals, but it has evolved a great deal since 1790, when President George Washington delivered his first annual address to Congress. One aspect in particular—the opposition response—is a modern practice that has developed to address a problem faced by Congress in its earliest years.1

In January 1790, as members of both the House and Senate gathered to begin the second session of the First Congress, President Washington wrote to John Adams (who as vice president also served as president of the Senate) that he wished to address both houses in a joint session as soon as they reached a quorum. The two houses achieved quorums on January 7 and informed the president they were ready to receive his message. On January 8, the president arrived at Federal Hall at 11:00 a.m. and proceeded to the Senate Chamber, where, accompanied by a few of his personal aides, he delivered his address to senators, representatives, and cabinet members. In his brief speech, Washington congratulated Congress on the “present favorable prospects of our public affairs,” highlighted the progress of the young nation, and made policy suggestions, including calling for the establishment of a national militia and a uniform system of currency.2

After Washington departed Federal Hall and representatives returned to their chamber, the Senate appointed a committee “to prepare and report the draft of an Address to the President of the United States, in answer to his Speech delivered this day to both Houses of Congress, in the Senate Chamber.” In keeping with the traditional ceremonial exchange between British Parliament and the King, both the Senate and House had offered a formal response to the president’s first inaugural address in April 1789, and both chambers prepared to follow that same practice with Washington’s annual message. Not all senators agreed, however, as to how the Senate should respond to the president’s speech. According to Pennsylvania senator William Maclay, South Carolina senator Pierce Butler thought that “the Speech was committed rather too hastily” and “made some remarks on it.” When Vice President Adams called Butler to order for his criticism, Maclay wrote that Butler “resented the call, and some Altercation ensued.”3

A few days later, the committee presented a draft response to the Senate, which assured the president that the Senate would address each issue that he mentioned, point by point. Maclay, who was becoming a staunch opponent of the Washington administration, objected to the response. He called it “the most Servile Echo” he ever heard, and while the Senate did amend some sections of the original draft, Maclay complained that many clauses were passed without roll-call votes, leaving opponents to accept them “in silent disapprobation.” Meanwhile, the House of Representatives followed the same procedure, meeting to collaborate on a response, a process that proved both “time-consuming and contentious.” Once the House and Senate finally approved their drafts, each body then agreed to wait on the president en masse at his residence to present their responses in person. Following these formal presentations, the president then delivered his own responses.4

The ceremonial spectacle of these proceedings struck some members as obsequious and unnecessary, including Maclay, who worried that the response could be considered by the president’s administration as a tacit approval of its policies. “It was a Stale ministerial Trick in Britain, to get the Houses of parliament to chime in with the speech, and then consider them as pledged to support any Measure which could be grafted on the Speech.” A foreign observer who witnessed both the president’s speech and Congress’s responses noted that the exchange “looked completely like that practiced in England between the King and Parliament” except for the fact that “the next day not one voice was raised in the two Houses to attack any part whatever of the address.” The opposition remained silent.5

As partisan factions developed during Washington’s administration, the process of drafting and agreeing to a single institutional response became impractical. Washington interpreted the Constitution’s directive “from time to time” to mean once a year, and every president since Washington has followed this precedent. This meant that year after year, both the Senate and House spent days, and sometimes weeks, during Washington’s presidency tediously debating their respective responses paragraph by paragraph, arguing over word choice and overall tone. In addition, those in the Senate minority remained frustrated with Senate responses that supported administration policies and ignored dissenting views.

In December 1795 Washington delivered his annual address at the first session of the Fourth Congress, six months after the Senate had convened in a special executive session to consider the controversial Jay Treaty. The Senate’s rancorous debate over the treaty had deepened the partisan divisions among senators, with the majority pro-administration Federalists supporting it and anti-administration Democratic Republicans voting in opposition. The Senate approved the treaty for ratification by the slimmest margin. In his speech, Washington referred to the treaty, declaring that the “summary of our affairs, with regard to the Foreign powers between whom and the United States controversies have subsisted . . . opens a wide field for consoling and gratifying reflections.”6

The treaty’s opponents felt neither consoled nor gratified. When the draft of the Senate’s response included similar praise for the treaty, the Democratic-Republicans objected. Virginia senator Stevens Thomson Mason argued that referring to the treaty in this way served only to rekindle animosities among senators. “The minority on that occasion were not now to be expected to recede from the opinions they held then, and they could not therefore join in the indirect self-approbation which the majority appeared to wish for.”7

Virginia senator Henry Tazewell not only objected to the passage about the treaty, but he questioned the practice of a congressional response altogether, asking “what had given rise to the practice of returning an answer of any kind to the President’s communication to Congress in the form of an Address? There was nothing . . . in the Constitution, or in any of the fundamental rules of the Federal Government which required that ceremony from either branch of the Congress.” Tazewell’s observation was true, but many in Congress clung tight to the pageantry and ceremonial trappings of the executive-legislative exchange.8

Despite the protests of the Democratic-Republicans, attempts to remove the offending passages from the Senate’s response failed. The Senate then approved what was essentially the majority’s response to the annual address on a party-line vote of 14-8. While responses to Washington’s remaining annual addresses and those of John Adams do not appear to have been debated quite as intensely, the strong Federalist majorities in the Senate of that era meant that the minority voice remained unheard.9

When Congress moved from Philadelphia to the newly created capital city of Washington in the District of Columbia in 1800, the tradition of the executive-legislative exchange continued. President Adams presented his final annual address to Congress in person at the Capitol, and both the Senate and House presented responses to the president at his new residence. Unlike Philadelphia, however, where Congress Hall was a mere block from the president’s residence, in the District of Columbia the President’s House was more than a mile from the Capitol, making the trip less convenient. This was one of the reasons given by President Thomas Jefferson in 1801 when he chose to send his message to Congress in writing. He further suggested that the Senate and House need not prepare their official replies:

The circumstances under which we find ourselves at this place rendering inconvenient the mode heretofore practiced, of making by personal address the first communications between the legislative and executive branches, I have adopted that by message, as used on all subsequent occasions through the session. In doing this I have had principal regard to the convenience of the legislature, to the economy of their time, to their relief from the embarrassment of immediate answers, on subjects not yet fully before them, and to the benefits thence resulting to the public affairs.10

For the rest of the 19th century, and into the 20th, presidents followed Jefferson’s example, and Congress stopped officially replying to the president. The annual message to Congress became a lengthy report that laid out the activities and financial needs of the executive branch and included policy recommendations and a summary of foreign affairs. This was the case until 1913, when Woodrow Wilson announced that he would read his annual address to Congress in person.

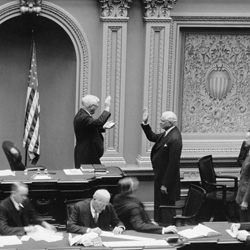

Wilson understood the power of public opinion in pressuring Congress to support his agenda, so he tailored his speech to appeal to a much wider audience—the American public. He kept the address short but visionary, hoping to persuade and move his audience through emotional rhetoric. According to press reports, Wilson’s in-person performance was a “triumph.” His successors continued the tradition of in-person delivery, and the State of the Union Address became a platform that elevated the priorities of the president and his party. Even more so than during the nation’s founding era, members of the opposing political party found themselves without a formal role to play in the annual event. The advent of television in the 1940s and ʼ50s and the shift of the speech delivery from daytime to prime time in 1965 further expanded the reach of the president’s message, prompting minority leadership in Congress to finally develop a coordinated response. In 1966 Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen and House Minority Leader Gerald Ford recorded a 30-minute rebuttal which aired on major television networks a week after the president’s speech. The opposition response was born.11

Today, the opposition response is broadcast live immediately following the president’s speech. It has become an integral part of this annual ritual, anticipated and discussed almost as much as the address itself—thanks in part to social media platforms. No doubt the Democratic-Republicans of the early 19th century would have appreciated this innovation. What began in the Senate and House as congressional responses expressing the approbation of the president’s majority party has evolved into an opposition response by the other national party, reflecting the complexity of both party politics and executive-legislative relations and demonstrating the delicate balance of power between discordant forces in our system of government.

Notes

1. U.S. Constitution, Article II, section 3.

2. Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 2nd sess., January 8, 1790, 102–4.

3. Ibid., 104; Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., 20, 22–23, 26–27; Kenneth R. Bowling and Helen E. Veit, eds., Diary of William Maclay and Other Notes on Senate Debates, vol. 9 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 180.

4. Bowling and Veit, Diary of William Maclay, 181; “A ‘Troublesome and Greatly Derided Custom’ — Answering the Annual Message,” History, Art, & Archives, United States House of Representatives, Whereas: Stories from the People’s House, https://history.house.gov/Blog/2016/January/1-12-LyonResponse/, accessed January 19, 2024.

5. Bowling and Veit, Diary of William Maclay, 181; Letter from Louis Guillaume Otto to Comte de Montmorin, January 12, 1790, in Charlene Bangs Bickford, Kenneth R. Bowling, Helen E. Veit, and William Charles diGiacomantonio, eds., Correspondence, Second Session: October 1789–14 March 1790, vol. 18 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 196–97.

6. Annals of Congress, 4th Cong., 1st sess., 11.

7. Ibid., 15–16.

8. Ibid., 21.

9. Ibid., 22–23.

10. Senate Journal, 7th Cong., 1st sess., December 8, 1801, 156.

11. James W. Ceaser, Glen E. Thurow, Jeffrey Tulis and Joseph M. Bessette, “The Rise of the Rhetorical Presidency,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 11, No. 2 (Spring, 1981): 158–71; “Wilson Triumphs with Message,” New York Times, December 3, 1913, 1.

|

| 202309 15Constitution Day 2023: The Senate’s Last Framer—Rufus King

September 15, 2023

Of the 55 delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787, 19 later served in the U.S. Senate, including New York senator Rufus King. Like other consequential individuals whose participation in America’s founding crossed over into the new federal republic, King’s experience as a framer later informed his efforts to implement the Constitution as a member of Congress. King served in the Senate longer than any other delegate to the Philadelphia convention—the Senate’s last framer—and became a respected and often outspoken elder statesman.

Of the 55 delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787, 19 of those constitutional framers later served in the U.S. Senate, including New York senator Rufus King. Like other consequential individuals whose participation in America’s founding crossed over into the new federal republic, King’s experience as a framer later informed his efforts to implement the Constitution as a member of Congress, bringing knowledge, continuity, and stability to the new government. A member of the Massachusetts delegation to the Constitutional Convention, King subsequently moved to New York and became one of the first two senators to represent that state in 1789. He went on to serve in the Senate longer than any other delegate to the Philadelphia convention—the Senate’s last framer—and became a respected and often outspoken elder statesman.

As historians have explained, the individuals chosen to attend the federal convention that resulted in the creation of a “partly federal and partly national” constitutional system “were not mere ‘theoretical’ politicians who were engaging in government for the first time.” They “were experienced veterans, many of whom had already been able to see the variants of democracy play out within their own states,” while others “knew firsthand the frustrations of governing” under the Articles of Confederation that preceded the constitutional government. This was certainly true of Rufus King.1

Just 32 years old when he attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787, King was already considered, as described by fellow delegate William Pierce of Georgia, a “man much distinguished for his eloquence and great parliamentary talents,” who “ranked among the Luminaries of the present Age.” Trained as a lawyer, he entered Massachusetts politics with service in the state’s general assembly before becoming a delegate to the Continental Congress. Taking leave of his post to attend the Philadelphia convention, King was present at every session and took notes—a valuable resource for historians. Considered “among the most capable orators” at the convention, his contributions were significant. He served on several major committees, including the important Committee on Postponed Matters and Committee of Style, which were charged with finalizing the document as the convention was ending. As historian Richard Welch concluded, King was “surely one of the most prominent members of the Convention at large.”2

After the ratification of the Constitution, when the First Congress convened in 1789, the 34-year-old King became the youngest senator of the time. King “came to the Senate with a record of solid achievement,” historian Roy Swanstrom explained, and he “was consistently among the most active Senators in committee work.” During his first Senate term, King played a key role in the creation and approval of the Jay Treaty, co-authoring with Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Chief Justice of the United States John Jay a series of published essays in defense of the controversial treaty with Great Britain. He also proved influential in establishing the First Bank of the United States and was elected one of the first 25 directors of the bank in 1791.3

In 1796 President George Washington appointed King to be minister to Great Britain, a position he held until 1803. Upon his return to the United States, King spent a decade out of public office before again being elected to the Senate in 1813. By this time, King was the “only senator who had sat in the body while Washington was President,” and was one of only two framers still serving in the Senate—along with New Hampshire’s Nicolas Gilman. When Gilman died in 1814, King became the last framer of the Constitution still serving in the Senate.4

Specializing in matters of finance and foreign relations, as well as maritime law, commerce, and public lands, King’s expertise was widely respected by his contemporaries. His skillful oratory often impressed his congressional colleagues, including a young, newly elected New Hampshire representative named Daniel Webster, who hailed King’s speaking ability as “unequalled.” When the Senate established its standing committee system in 1816, King was assigned to two of the most important panels—Foreign Relations and Finance. “In the years to come he would apply his knowledge and experience” to that committee work, noted a biographer, and “in debates and roll calls on the Senate floor, he was a watchdog, sniffling out signs of wastefulness and partisan aims.”5

By the time the Senate tackled the difficult issue of the Missouri crisis in 1819 and 1820, King was a respected elder statesman. His status was tested, however, when the question of expanding slavery in new western states threatened to disrupt the delicate balance between slave states and free states, especially in the Senate, where states were given equal representation. King insisted that Congress had a right to exclude slavery from new states. This position alienated colleagues of slaveholding states but bolstered support in the northern states. King’s speeches rallied opposition to the proposed compromise that sought to admit Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state while prohibiting slavery in the territories north of the 36º 30' parallel.

King had consistently opposed the expansion of slavery throughout his career. While serving in the Continental Congress in the 1780s, he had introduced a resolution providing that there should be neither "slavery nor involuntary servitude" in the Northwest Territory, language that was ultimately incorporated into the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. During the Constitutional Convention, foreseeing the growing divide between slave and free states, he had expressed doubts about the three-fifths compromise that determined the method by which enslaved Americans were to be counted for purposes of taxation and representation. Although King had accepted the three-fifths compromise as a necessary concession to slaveholding states in order to gain adoption of the Constitution, by 1803, when the purchase of the vast Louisiana Territory raised new possibilities for the expansion of slavery, he believed that the three-fifths provision was one of the “greatest blemishes” on the Constitution.6

In 1819, as senators debated the issue of expanding slavery into Missouri and other western states, King stood in opposition, drawing on his participation in the constitutional debate over the three-fifths compromise to frame his argument. “The equality of rights, which includes an equality of burdens, is a vital principle in our theory of government,” he explained, “and its jealous preservation is the best security of public and individual freedom.” He maintained that “the departure from this principle in the disproportionate power and influence, allowed to the slave holding states” through the three-fifths compromise, “was a necessary sacrifice to the establishment of the constitution,” but such a compromise was no longer acceptable. “The effect of this concession has been obvious in the preponderance which it has given to the slave holding states over the other states.” He continued:

Nevertheless it is an ancient settlement, and faith and honour stand pledged not to disturb it. But the extension of this disproportionate power to the new states would be unjust and odious. The states whose power would be abridged, and whose burdens would be increased by the measure, cannot be expected to consent to it; and we may hope that the other states are too magnanimous to insist on it.7

King’s Senate speeches were printed and distributed as a pamphlet, fueling the already heated debate over slavery’s possible westward expansion. Given King’s status as a veteran statesman, the publication received much attention. According to historian Robert Ernst, “The speeches became a center of acrimonious controversy.” The pamphlet “has largely contributed to kindle the flame now raging throughout the Union on that question, and which threatens its dissolution,” John Quincy Adams (then serving as Secretary of State) wrote in his diary. “A whirlwind of anti-Missouri feeling swept over the North,” noted historian Homer Hockett. “Mass meetings were held and resolutions passed in open opposition to the extension of slavery into the new states,” commented historian Joseph L. Arbena, who wrote that “King appeared to be the source of much of this agitation.” His speeches and “ideas formed the bases for many of the essays, memorials, and speeches presented in support of his stand.” Observing King’s influence over the Missouri debate, Boston journalist and author William Tudor wrote to King in February 1820: “I have been convinced that it is chiefly owing to you that the nation has been awakened to examine its consequences.” Describing King’s fervor in the Missouri debate, Adams concluded, “King has made a desperate plunge into it, and has thrown his last stake upon the card.”8

While King’s speeches strengthened the opposition to the Missouri Compromise, they also stirred suspicions about the veteran senator’s motives. Critics, particularly those in favor of the compromise, accused King of using the crisis for his own political gain and to realign the parties around the issue and establish himself as a leader of a new party. Adams rejected such notions, arguing, “There is not a man in the Union of purer integrity than Rufus King.” Historians have tended to agree with Adams. “Although he would have welcomed a new political alignment of northern Republicans and the few remaining Federalists,” wrote Ernst, “there is no credible evidence that he plotted to bring this about, nor was he motivated by personal ambition for power.” Nevertheless, the suspicions cast upon King’s motives aided in diminishing the effectiveness of his influence upon the debate, contributing to the ultimate failure of his position.9

Despite the controversies of the Missouri crisis, King remained a respected and trusted public figure. In 1821 the Senate elected him as chairman of the influential Foreign Relations Committee—despite the fact that he was in the minority party, one of only four remaining Federalists in the Senate. Even those who had been disappointed by King’s position in the Missouri debate continued to hold him in high esteem. One admirer, Virginia representative John Randolph, remarked, “Ah, sir! only for that unfortunate vote on the Missouri Question, he would be our man for the Presidency. He is, Sir, a genuine English gentleman of the old school, just the right man for these degenerate times; but, alas! it cannot be.”10

King was both an ardent Federalist and an esteemed national leader whose link with the past, and particularly to his role as constitutional framer, garnered an admiration that eclipsed partisanship. “A venerable Senator, he was a sort of ‘Mr. Federalist,’" Ernst observed. Even as the Federalist influence declined, Ernst continued, “Rufus King's reputation as an elder statesman brightened.” His service in the Senate, which continued until 1825, extended well beyond any of the other 19 delegates to the Constitutional Convention who later became senators. A Massachusetts colleague, Harrison G. Otis, assessed the importance of King’s continuing service. “You prevent a great deal of mischief and keep in check the framers of crude projects and cunning devices,” Otis stated to King in 1823, adding, “whoever writes your epitaph…may be able to say that you continued many years at your post, the last of the Romans.” Rufus King, elder statesman, was the Senate’s last framer.11

Notes

1. John R. Vile, The Men Who Made the Constitution: Lives of the Delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2013), xx; David O. Stewart, The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007), 25.

2. “Notes of Major William Pierce on the Federal Convention of 1787,” The American Historical Review 3, no. 2 (January 1898): 325; National Park Service, Signers of the Constitution: Historic Places Commemorating the Signing of the Constitution (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976), 180–81; Richard E. Welch, Jr., “Rufus King of Newburyport: The Formative Years (1767–1788),” Essex Institute Historical Collections 96, no. 4 (October 1960): 267.

3. Roy Swanstrom, The United States Senate 1787–1801: A Dissertation on the First Fourteen Years of the Upper Legislative Body, reprinted as S. Doc. 99-19, 99th Cong., 1st sess. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1985), 45, 271–72.

4. Robert Ernst, Rufus King: American Federalist (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), 322.

5. Ernst, Rufus King, 327, 353.

6. Welch, Jr., “Rufus King of Newburyport,” 248; Joseph L. Arbena, “Politics or Principle? Rufus King and the Opposition to Slavery, 1785–1825,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 101, no. 1 (January 1965): 64–65; Robert Ernst, “Rufus King, Slavery, and the Missouri Crisis,” The New York Historical Society Quarterly 46, no. 4 (October 1962): 364.

7. Rufus King, The Substance of Two Speeches, Delivered in the Senate of the United States, on the Subject of the Missouri Bill, (Philadelphia: Clark & Raser, printers, 1819), 6–7, Library of Congress collection, accessed on August 29, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/item/09020866/.

8. Ernst, “Rufus King, Slavery, and the Missouri Crisis,” 367; Charles F. Adams, ed., Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1875), vol. 4, 517, 526; Homer C. Hockett, "Rufus King and the Missouri Compromise,'' Missouri Historical Review 2 (April 1908): 216; Arbena, “Politics or Principle?” 72; Charles R. King, ed., The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King: Comprising His Letters, Private and Official, His Public Documents and His Speeches (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900), vol. 6, 272.

9. Adams, Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, vol. 5, 13; Ernst, “Rufus King, Slavery, and the Missouri Crisis,” 382.

10. Ernst, Rufus King, 384–85; William Cabell Bruce, John Randolph of Roanoke, 1773–1833: A Biography Based Largely on New Material (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1922), 612.

11. Ernst, “Rufus King, Slavery, and the Missouri Crisis,” 373–74; Ernst, Rufus King, 407–9.

|

| 202304 4Treasures from the Senate Archives: Legislative-Executive Relations

April 4, 2023

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the selection of historic records featured in this month’s “Senate Stories,” which highlight the complex relationship between the Senate and the president.

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the selection of historic records featured in this month’s “Senate Stories,” which highlight the complex relationship between the Senate and the president.

Among the foundational principles of the U.S. Constitution is the separation of powers. In establishing three distinct branches of government—legislative, executive, and judicial—the Constitution divides authority to create the law, implement and enforce the law, and interpret the law. At the same time, many powers exercised by one branch may be shared with another. This system of checks and balances invites both compromise and conflict among the branches, especially between the legislative and executive, and prevents the consolidation of power in any single branch. For example, the Senate’s “advice and consent” is required for executive functions such as nominations and treaties. Conversely, the president has the power to veto legislation; however, Congress may overturn the veto with a two-thirds majority of those present and voting in both houses.1

The constitutional structure that provides for checks and balances is expansive and complex by design, generating an interdependence between the Senate and the executive branch that, combined with transient political interests, has historically demonstrated moments of high conflict as well as examples of great cooperation. This collection of historic documents from the Senate’s archives highlights the collaborations and the struggles that have defined the relationship between the Senate and the president. Each document, while capturing a specific moment in time with unique political conditions at play, also provides a broader view of the constitutional system of government in action, specifically the foundational principle of separation of powers and the complex system of checks and balances.

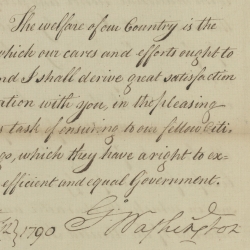

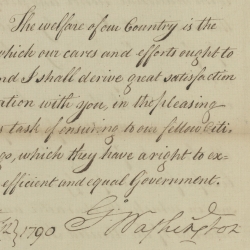

George Washington's First Inaugural Address, 1789

When George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the United States on April 30, 1789, he delivered this address to a joint session of Congress, assembled in the Senate Chamber in New York City’s Federal Hall. While this first occasion was not the public event we have come to expect, Washington's speech nevertheless established the enduring tradition of presidential inaugural addresses. Early presidential messages, including inaugural addresses and annual messages (now known as State of the Union addresses), are included in Senate records at the National Archives.

Although noting his constitutional directive as president "to recommend to your consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient," Washington refrained from detailing his policy preferences regarding legislation. Rather, on the occasion of his inaugural, he stated his confidence in the abilities of the legislators, insisting, "It will be…far more congenial with the feelings which actuate me, to substitute, in place of a recommendation of particular measures, the tribute that is due to the talents, the rectitude, and the patriotism which adorn the characters selected to devise and adopt them."

Message from President Thomas Jefferson to Congress Regarding the Louisiana Purchase, 1804

Treaty powers are among those shared by the president and the Senate. The Constitution provides that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur" (Article II, section 2). In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson's administration negotiated a treaty with France by which the United States purchased the vast Louisiana Territory. Questions arose concerning the constitutionality of the purchase, but Jefferson and his supporters successfully justified the legality of the acquisition. On October 20, 1803, the Senate approved the treaty for ratification by a vote of 24 to 7. The territory, which encompassed more than 800,000 square miles of land, now makes up 15 states stretching from Louisiana to Montana. In this congratulatory message to Congress dated January 16, 1804, President Jefferson reported on the formal transfer of the land to the United States and referenced the December 20, 1803, proclamation announcing to the residents of the territory the transfer of national authority.

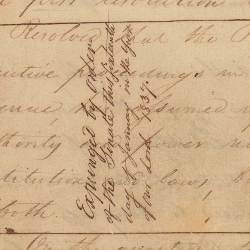

Page from the Senate Journal Showing the Expungement of a Resolution to Censure President Andrew Jackson, 1834

The March 28, 1834, censure of President Andrew Jackson represents a notably contentious episode in the executive-legislative relationship. For two years, Democratic president Andrew Jackson had clashed with Senator Henry Clay and his allies over the congressionally chartered Bank of the United States. The dispute came to a head when President Jackson, who had opposed the creation of the Bank, ordered the removal of federal deposits from the Bank to be distributed to several state banks. When his first Treasury secretary refused to do so, Jackson fired him during a Senate recess and appointed a new Treasury secretary, who carried out his orders. Senator Clay and his allies, who supported the Bank, believed that President Jackson did not have the constitutional authority to take such action, and they found the explanation given for moving the federal deposits “unsatisfactory and insufficient.” Clay introduced the resolution to censure the president, charging that Jackson had “assumed the exercise of a power over the Treasury of the United States not granted him by the Constitution and laws.” After extensive debate, the censure resolution passed. Jackson responded by submitting to the Senate a 100-page message arguing that the Senate did not have the authority to censure the president. The Senate again rebuffed the president by refusing to print the lengthy message in its Journal.2

Over the next three years, Missouri Democrat and Jackson ally Thomas Hart Benton campaigned to expunge the censure resolution from the Senate Journal. In January 1837, after Democrats regained the majority in the Senate, Senator Benton succeeded. On January 16, the secretary of the Senate carried the 1834 Journal into the Senate Chamber, drew careful lines around the text of the censure resolution, and wrote, “Expunged by order of the Senate."

President Abraham Lincoln's Nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to be Lieutenant General of the U.S. Army, 1864

Like treaty powers, the Constitution requires that the Senate serve as a check on the president's nomination authority. The president nominates federal judges, members of the cabinet, and military officials, among others, whose nominations are confirmed with the advice and consent of the Senate. This remarkable document dated February 29, 1864, representing a critical moment in the Civil War, is President Abraham Lincoln's nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to be lieutenant general of the U.S. Army, at the time the United States’ highest military rank. Previously, only two men had achieved that rank—George Washington and Winfield Scott—and Scott’s had been a brevet promotion. To facilitate Grant’s nomination and ensure his superior status among military officers, Congress passed a bill to revive the grade of lieutenant general and authorize the president "to appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, a lieutenant-general, to be selected among those officers in the military service of the United States . . . most distinguished for courage, skill, and ability." The Senate confirmed Lincoln's nomination of Grant on March 2, 1864.

Letter from President Woodrow Wilson to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, 1919

A unique event in legislative-executive relations occurred on August 19, 1919, when President Woodrow Wilson offered testimony before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations on the Treaty of Versailles, then under consideration by the committee. The meeting, convened in the East Room of the White House, stood “in contradiction of the precedents of more than a century,” the Atlanta Constitution reported, noting the rarity of a president offering testimony before a congressional committee.3

The Treaty of Versailles ended military actions against Germany in World War I and created the League of Nations, an international organization designed to prevent another world war. President Wilson had led the U.S. delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and had been a principal architect of the treaty. For months, Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Henry Cabot Lodge had encouraged the president to seek the advice of the Senate while negotiating the treaty’s terms, but Wilson chose to negotiate on his own. Personally invested in the treaty’s adoption, the president hand-delivered it to the Senate on July 10, 1919, and urged its approval for ratification in an unusual speech before the full Senate.

Under Senate rules, the treaty went to the Foreign Relations Committee for consideration, which held public hearings from July 31 to September 12, 1919. Among the most vocal critics of the proposed treaty was Lodge, who was also the Senate majority leader. Lodge opposed several elements of the treaty, particularly those related to U.S. participation in the League of Nations. On behalf of the Foreign Relations Committee, Lodge asked Wilson to meet with the committee to answer senators’ questions. With this letter, President Wilson agreed to Lodge's request and proposed the August 19 date at the White House.

Ultimately, Lodge’s committee insisted on a number of “reservations” to the treaty, but Wilson and Senate proponents of the treaty were unwilling to compromise on terms. Consequently, on November 19, 1919, for the first time in its history, the Senate rejected a peace treaty.

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, 1973

Under the Constitution, the president is permitted to veto legislative acts, but Congress has the authority to override presidential vetoes by two-thirds majorities of both houses. This document provides a comprehensive example of these constitutional checks and balances in action. In 1973 Congress passed S.518, which sought to abolish the offices of the director and deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget and reestablish those positions with a new requirement that they be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. The bill’s proponents argued that because these positions had evolved to wield significant power, they ought to be subject to Senate confirmation.

President Richard Nixon vetoed the bill on May 18, claiming it to be unconstitutional. “This step would be a grave violation of the fundamental doctrine of separation of powers,” Nixon stated. While the Senate achieved the necessary two-thirds majority to override the veto, the House did not, and Nixon’s veto was sustained. Congressional efforts to override Nixon’s veto were recorded by the secretary of the Senate and clerk of the House of Representatives on the reverse side of the bill.

The system of checks and balances set forth by the Constitution is a complex one, creating a legislative-executive relationship that is sometimes adversarial and at other times cooperative, but always interdependent. Illustrating the Senate's broad-ranging responsibilities and the integral role the Senate has played in this constitutional system, these treasured documents from the Senate’s archives help us to gain a better understanding of the conflicts and compromises that have historically defined the relationship between the Senate and the president.

Notes

1. Matthew E. Glassman, "Separation of Powers: An Overview," Congressional Research Service, R44334, updated January 8, 2016, 2.

2. Senate Journal, 25th Cong., 2nd sess., March 28, 1834, 197.

3. “Wilson Meets Senators in Wordy Duel,” Atlanta Constitution, August 20, 1919, 1.

|

| 202209 17Constitution Day 2022: Treatymaking Power and George Washington's Visit to the Senate

September 17, 2022

The Constitution states that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur." This defines how consent is given but does not explain how the Senate offers its advice. Many framers envisioned the Senate as an executive council that would discuss a treaty with the president as it was being negotiated. When President George Washington visited the Senate for that purpose in 1789, however, it became clear that the framers’ view might not prevail.

Constitutional Foundations of Treatymaking

When the framers of the Constitution considered the question of treatymaking at the Federal Convention held in Philadelphia in 1787, they originally proposed giving the Senate the sole power to make treaties. As the debate ensued, however, objections arose to depositing the full scope of this complex diplomatic power within the legislative branch. Ultimately, the framers decided that treatymaking would be a concurrent power, shared by the executive and the legislative branches. Article II, section 2 of the Constitution states that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur."

In this shared responsibility, the Senate would check presidential power, give the president the benefit of its advice and counsel, and safeguard the sovereignty of the states by providing each state with an equal vote in the treatymaking process. The president would represent the national interest in treatymaking and allow for unity and efficiency. As Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist, No. 75, the treatymaking power “seems…to form a distinct department, and to belong properly neither to the legislative nor to the executive. The qualities elsewhere detailed, as indispensable in the management of foreign negotiations, point out the executive as the most fit agent in those transactions; while the vast importance of the trust, and the operation of treaties as laws, plead strongly for the participation of the whole or a part of the legislative body in the office of making them.”1

While the Constitution defines the manner in which consent is given by stipulating that two-thirds of senators present must agree to a treaty, it does not explain how the Senate should offer its advice. “This bare grant tells us…merely that they were the joint possessors of this great power,” one scholar noted. The Constitution’s “elasticity in details…left to successive Senates and to successive presidents the problem and the privilege of determining under the stress of actual government the precise manner in which they were to make the treaties of the nation.”2

The Senate as Executive Council

Many of the framers of the Constitution expected that the Senate would meet with the president in the manner of an executive council to confer about the details of a treaty as it was being negotiated. When the Senate began to consider treaties in 1789, however, it soon became clear that the framers’ view might not prevail. A formative event took place on Saturday, August 22, 1789, at New York City’s Federal Hall when President George Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox visited senators in their Chamber “to advise with them on the terms of the Treaty to be negotiated with the Southern Indians.”3

Senators of the First Congress and President Washington were well aware that every action they took established precedents, and they often showed great thoughtfulness and foresight in their proceedings. Such was the case with the question of handling communications between senators and the president regarding the Senate’s advice and consent powers. Specifically, should that communication be in writing or in person? It was actually the first Senate rejection of a presidential nomination (also requiring the Senate's advice and consent) that precipitated a careful discussion about the form of communication with the president. On August 5, 1789, the day the nominee was rejected, a motion had been made that the Senate’s “advice and consent to the appointment of officers should be given in the presence of the President.” The Senate then appointed a committee of three to confer with President Washington “on the mode of communication proper to be pursued between him and the Senate, in the formation of treaties, and making appointments to offices.”4

The committee met with the president twice, on August 8 and August 10. “In all matters respecting Treaties,” Washington asserted in the first meeting, “oral communications seem indispensably necessary—because in these a variety of matters are contained, all of which not only require consideration, but some of them may undergo much discussion—to do which by written communications would be tedious without being satisfactory.” Given the necessity of an in-person meeting, Washington then posed several questions as to where such meetings should take place and what protocol should be followed. “If in the Senate Chamber,” for example, “how are the President and Vice President to be arranged?”5

Washington made additional assertions in the second meeting on August 10. In exercising its powers of advice and consent, Washington noted, the Senate “is evidently a Council only to the President”; therefore, “not only the time but the place and manner of consultation should be with the President.” He made an important distinction between the consideration of nominations and treaties, however, stating that treaties were “perhaps as much of a legislative nature” as executive, and so there would be occasions when the president should visit the Senate Chamber in person to make his propositions regarding the terms of a treaty. “The inclination or ideas of different Presidents may be different,” Washington predicted, suggesting the Senate needed to be flexible in the process by which it provides its advice and consent.6

In its report, the Senate committee agreed with the president. Like Washington, the committee also predicted “that the opinions both of the President and the Senate as to the proper manner may be changed by experience.” The committee’s resolution, adopted by the Senate on August 21, 1789, provided for the president to meet with the Senate in its Chamber. On the same day this resolution was adopted, Tobias Lear, President Washington’s secretary, delivered a message stating the president would meet with senators the following day “to advise with them on the terms of the Treaty to be negotiated with the Southern Indians.”7

President Washington Visits the Senate

When President Washington and Secretary Knox arrived in the Senate Chamber on Saturday, August 22, they presented the Senate with a series of questions related to upcoming treaty negotiations. The official record of this proceeding, included in the Senate Executive Journal, offers little insight into what happened in the Chamber that day, merely summarizing the issues and listing seven questions regarding instructions to the commissioners who would negotiate the treaty. According to the Executive Journal, the first question was postponed and the second was answered in the negative. Secretary of the Senate Samuel Otis recorded in his journal that a motion was made to refer the remaining questions to a committee, but Washington thought it improper, and the motion was rejected. The Executive Journal indicated that the Senate ultimately postponed consideration of the remaining questions until the following Monday.8

The only other contemporary account of Washington’s visit to the Chamber that day comes from the diary of William Maclay, a Pennsylvania senator who was a frequent critic of the president. Maclay stated that the meeting was awkward and tense. He noted that the reading of the president’s treaty propositions was drowned out by the noise of Manhattan traffic, making it difficult for senators to grasp the details. “Carriages were driving past and such a Noise, I could tell it was something about Indians, but was not master of one Sentence of it,” he complained.

When the president’s first question, regarding relations with the Cherokees, was put before the Senate, “There was a dead pause,” Maclay noted. “Mr. Morris whispered (to) me, we will see who will venture to break silence first.” Maclay continued, “I rose reluctantly indeed…, it appeared to me, that if I did not, no other one would. And we should have these advices and consents ravish’d in a degree from Us.” Maclay called for the reading of related treaties and other documents, arguing that the Senate had a duty to be fully informed on the subject. Casting his eye on Washington, the Pennsylvania senator noted the president “wore an aspect of Stern displeasure.” As the discussion continued, Maclay concluded that “there appeared an evident reluctance to proceed.” He suggested to Pennsylvania’s Robert Morris that the issues be referred to a committee. “My reasons,” he wrote, “were that I saw no chance of a fair investigation of subjects while the President of the U.S. sat there with his Secretary of War, to support his Opinions and over awe the timid and neutral part of the Senate.”

When Morris moved to have the matter referred to a committee of five, some senators “grumbled some objections,” with South Carolina’s Pierce Butler arguing that the Senate was sitting as a council and that “no council ever committed anything.” Maclay then gave a speech in support of a committee. (“I thought I did the subject justice,” he added in his diary.) As he sat down, Maclay recorded, Washington “started up in a violent fret,” exclaiming, “‘This defeats every purpose of my coming here!’” According to Maclay, Washington “soon cooled, however, by degrees,” and while he objected to the referral to committee, he indicated that he would accept a postponement until Monday. After the motion for a committee was withdrawn and the Senate agreed to postpone, Maclay wrote, the president withdrew “with a discontented Air” and a “sullen dignity.”

Maclay, a vocal opponent of the growth of centralized government power, interpreted the encounter as a contest over the Senate’s equal power in treatymaking. “I cannot now be mistaken,” he wrote in his diary, “the President wishes to tread on the Necks of the Senate…he wishes Us to see with the Eyes and hear with the ears of his Secretary only…And to bear down our deliberations with his personal Authority and Presence.” If the Senate did not take its own counsel and study before offering its advice, Maclay worried, it would contribute little to the treatymaking process and surrender its vital constitutional role. “Form only will be left for Us,” he lamented. “This will not do with Americans.” Maclay was disappointed that a committee was not appointed to consider the issues at hand, but the agreement to postpone offered the Senate the opportunity to study and debate the issues before providing its decision.

Washington returned to the Senate Chamber on Monday and, according to Maclay, “wore a different aspect from what he did Saturday. He was placid and Serene and manifested a Spirit of Accommodation.” The president watched as the Senate proceeded with its “tedious debate” of the remaining questions.9

Washington never again returned to the Senate in person to ask its advice and consent. From then on, he would communicate with the Senate only in writing. Despite the concerns that Maclay confided to his diary, there is little evidence to suggest that Washington intended to intimidate the Senate with his presence or to pressure senators into adopting a particular set of negotiating goals or instructions. Nevertheless, the unwieldy process of Senate deliberation, and perhaps senators’ insistence on studying the issues independently, seems to have discouraged the president from returning to the Chamber. He chose afterwards not to meet with the Senate as an “executive council” as had been envisioned. In the years that followed, Washington’s administration kept the Senate abreast of information related to the formation of treaties, but the president did not consult the full Senate in detail on treaty negotiations, although he did at times consult key groups of senators. When Washington pursued the most contested treaty of his administration, the Jay Treaty with Britain, he worked with a select group of supportive senators to determine the goals of the agreement and secure its approval in the Senate.10

It would be up to future presidents and senators to continue to shape the practice by which the Senate fulfills its constitutional duty of advice and consent. Some presidents have sought advice from the Senate on particular treaties, and a number of presidents have named individual senators to negotiating teams to help build support among their colleagues for the administration’s proposals. For the most part, however, senators have been left to assert their influence in the treatymaking process after a president submits a treaty for their approval. Presidents continue to conduct treaty business with the Senate in writing, although Woodrow Wilson broke with precedent in 1919. He presented the Treaty of Versailles—the peace agreement following World War I that he had personally helped to negotiate—to senators in the Chamber and urged its approval. While the Senate has approved the vast majority of treaties submitted, it has also required amendments and reservations to win that approval and has rejected or failed to act on treaties that did not garner enough support.

The Constitution established the framework of a new federal government, but it was not long before elected officials were confronted with difficult choices about how to exercise the powers it designated, especially when, as in treatymaking, those powers were shared between branches. The August 22 encounter between President George Washington and the Senate during the First Congress became an early milestone in the evolution of those shared powers. As the Senate’s committee report noted, the manner in which the Senate and the executive would put the Constitution’s treatymaking powers into operation would inevitably "be changed by experience."11

Notes

1. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Treaties and Other International Agreements: The Role of the United States Senate; A Study Prepared for the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, by the Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 106th Cong., 2nd sess., January 2001, S. Prt. 106-71, 2, 28; Alexander Hamilton, “The Federalist No. 75, [26 March 1788],” Founders Online, accessed August 31, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0227. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 4, January 1787–May 1788, ed. Harold C. Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962), 628–33.]

2. Ralston Hayden, The Senate and Treaties, 1789–1817: The Development of the Treaty-Making Functions of the United States Senate During Their Formative Period (New York: Macmillan, 1920), 2.

3. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Treaties and Other International Agreements, 2, 27; Message of President George Washington Requesting that the Senate Meet to Advise Him on the Terms of the Treaty to Be Negotiated with the Southern Indians, August 21, 1789, Anson McCook Collection of Presidential Signatures, 1789–1975, Record Group 46, Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

4. Senate Executive Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., August 5–6, 1789, 16.

5. George Washington to Senate, August 8, 1789, George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks 1754–1799: Letterbook 25, April 6, 1789–March 4, 1791, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, accessed August 31, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mgw2.025/?sp=73&st=text.

6. George Washington to Senate, August 10, 1789, George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks 1754–1799: Letterbook 25, April 6, 1789–March 4, 1791, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, accessed August 31, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mgw2.025/?sp=75&st=text.

7. Report of the Committee Appointed to Confer with the President on the Mode of Communication Proper to be Pursued Between Him and the Senate in the Formation of Treaties and Making Appointments to Offices, August 20, 1789, (SEN 1A-D1) Record Group 46, Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Senate Executive Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., August 21, 1789, 19; Message of President George Washington Requesting that the Senate Meet to Advise Him on the Terms of the Treaty to Be Negotiated with the Southern Indians, August 21, 1789.

8. Senate Executive Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., August 22, 1789, 19–23; Secretary of the Senate Journal on President George Washington's Visit to the Senate Regarding the Treaty with the Southern Indians, August 22, 1789, Record Group 46, Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

9. Edgar S. Maclay, ed., Journal of William Maclay, United States Senator from Pennsylvania, 1789–1791 (New York: D.A. Appleton and Company, 1890), 128–33, accessed February 28, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/collections/century-of-lawmaking/articles-and-essays/journals-of-congress/maclays-journal/.

10. Hayden, The Senate and Treaties, 103–6.

11. Report of the Committee Appointed to Confer with the President, August 20, 1789.

|

| 202112 3Beer by Christmas

December 3, 2021

The Christmas season often brings a sense of joyous anticipation as people celebrate the holiday, enjoy family gatherings, and eagerly await the opening of gifts. Would that special “something” be under the tree? In 1932 that “something” on many people’s wish list was beer.

The Christmas season often brings a sense of joyous anticipation as people celebrate the holiday, enjoy family gatherings, and eagerly await the opening of gifts. Would that special “something” be under the tree? In 1932 that “something” on many people’s wish list was beer.

The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in December 1917 and ratified by the states in January 1919, banned the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” To enforce the amendment, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act (named for its sponsor, Representative Andrew Volstead of Minnesota), in October 1919. Passed over a veto by President Woodrow Wilson, the Volstead Act defined an “intoxicating beverage” as anything that contained more than .5 percent alcohol. While much of the campaign against alcohol in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had focused on hard liquor, the act’s strict definition also outlawed beer and wine.1

After a decade of Prohibition and the challenges of enforcement—even in the halls of Congress—American politicians in the 1920s split between the “drys,” who wanted to maintain Prohibition, and the “wets,” who wanted it repealed. Both political parties were internally divided over the issue and for more than a decade refrained from adopting a national stance on the question of alcohol. In 1932, however, with the nation suffering through the Great Depression, the Democrats adopted a party platform that supported repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment and modification of the Volstead Act to allow for the manufacture of beer. The Republicans stopped short of endorsing repeal that year—their party platform stated the issue “was not a partisan political question”—but did support altering the amendment to allow states to decide the issue for themselves.2

With Franklin Roosevelt’s victory in the 1932 presidential election and Democratic majorities elected to the House and Senate, many believed that the end of the Prohibition Era was imminent. The election had been largely a referendum on economic issues, but popular majorities throughout the country had expressed support for legalizing alcohol again. In the November election, nine states voted to repeal their Prohibition statutes, and two others approved referenda supporting national repeal. Elected officials, including Louisiana senator Huey Long, began to state optimistically that Congress might deliver “beer by Christmas.” Throughout the country, beer producers, pubs, and taverns quietly made preparations in anticipation of serving beer by December 25.3

As Congress returned for a lame-duck session in December, which would last until March 4, 1933, the “wets” arrived in Washington ready to act. Speaker of the House John Nance Garner, soon to be Vice President Garner, made repeal of the Prohibition amendment the first order of business, but on December 5 Garner’s resolution fell six votes short of the necessary two-thirds majority. The “drys” had won that round, but the “wets” did not concede defeat. “Congress will legalize some sort of beer before Christmas,” Garner announced.4

House Democrats had already held meetings in November before the opening of the session, including with President-elect Roosevelt, and scheduled committee hearings for December 7 to consider a beer bill. Representative James Collier, chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, drafted a bill to legalize beer containing less than 2.75 percent alcohol, which he deemed “non-intoxicating.” Collier’s bill also provided for taxation of beer sales, which allowed supporters to emphasize that legalization would provide badly needed revenue to the federal government in the face of growing budget deficits. Beer producers urged the House to increase the allowable alcohol content to 3.2 percent and promised that they could employ 300,000 people and provide the government with $400 million in revenue over the next year.5

Despite a sense of urgency, the House committee did not report the bill until December 15, and another week passed before the House passed the bill on the 22nd. The prospect of “beer by Christmas” was now in the hands of the Senate. Could the Senate act quickly enough to make the Christmas deadline?6

On December 23, the Senate referred the Collier bill to the Judiciary Committee. Since it included a beer tax, the bill also went to the Finance Committee. With time running out, Republican senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut—who had just lost his re-election campaign and was now a lame-duck senator—attempted to bypass the committees and get quick action. Bingham had introduced his own beer bill at the start of the previous session of Congress. The Committee on Manufactures had considered his bill but reported it to the full Senate with the recommendation that it not pass. Despite the adverse report, the bill was still available on the Senate calendar. Believing that the political situation had changed, Bingham moved to call up his bill. He intended to amend it by substituting the bulk of the Collier bill for his, predicting the amended bill would promptly pass the Senate.7

When Bingham made his motion to proceed to his bill, however, Democratic Leader Joseph Robinson of Arkansas—soon to be majority leader—applied the brakes. Would any beer, even 3.2 percent beer, be constitutional under the Eighteenth Amendment, Robinson pondered? He insisted that the decision required more careful attention and should not be made with “undue haste.” As the popularity of repeal grew nationwide and Democrats prepared to take the majority on March 4, partisan gamesmanship was also at play. Robinson charged the Republican Bingham of attempting to “embarrass” and upstage the Democrats. As one reporter wrote, “The Democrats let it be known that they had no intention of letting a Republican lame duck steal both the show and the beer bill.” Consequently, Bingham watched his motion fail by a vote of 23–48. Frustrated, he complained that America wouldn’t see beer even by Valentine’s Day.8