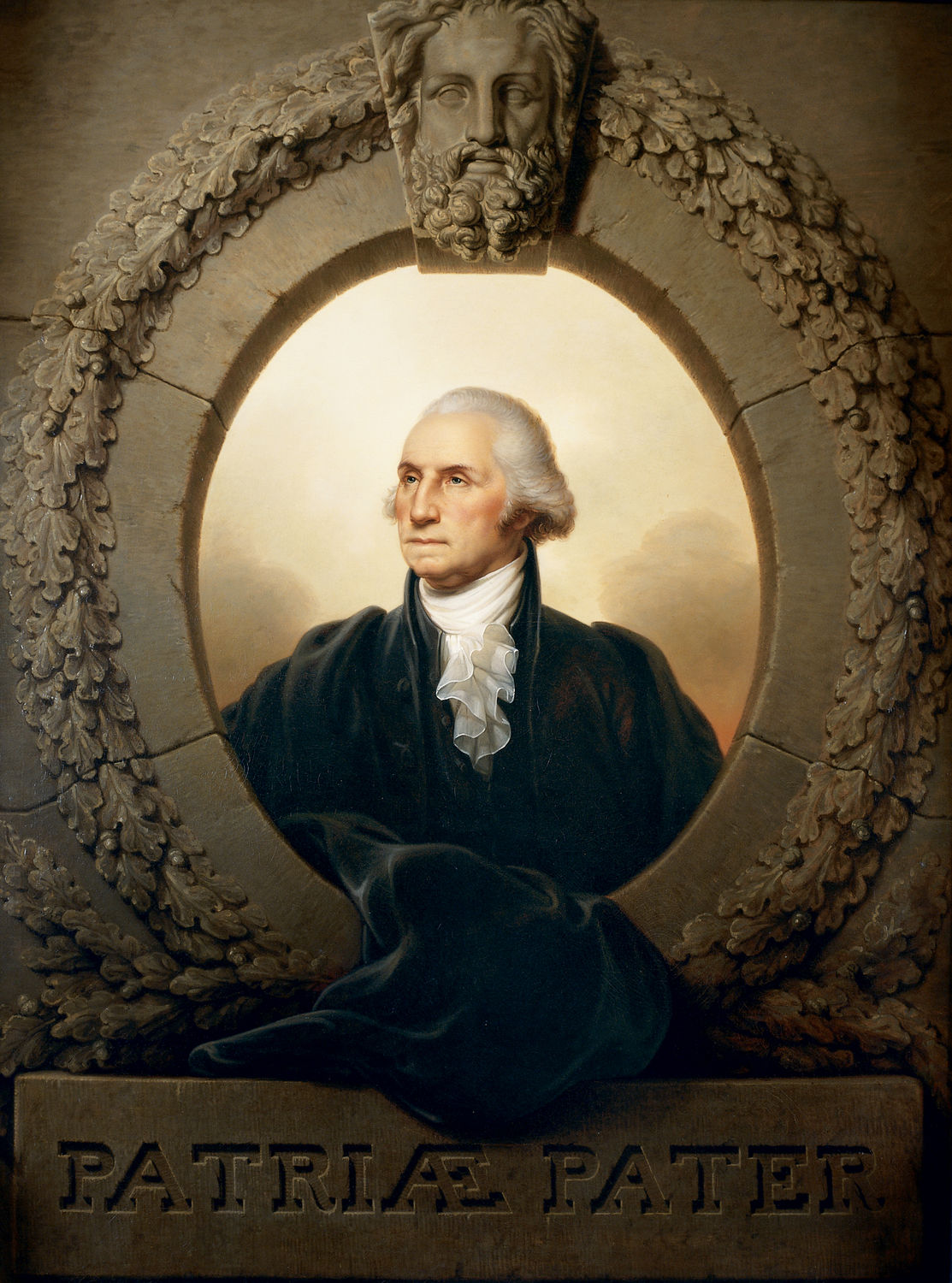

| Title | George Washington (Patriæ Pater) |

| Artist/Maker | Rembrandt Peale ( 1778 - 1860 ) |

| Date | 1824 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | Sight: h. 71.31 x w. 53.81 in. (h. 181.1274 x w. 136.6774 cm)

Framed: h. 89.25 x w. 71.75 x d. 8.75 in. (h. 226.695 x w. 182.245 x d. 22.225 cm) |

| Credit Line | U.S. Senate Collection |

| Accession Number | 31.00001.000 |

In 1795, at the age of 17, Rembrandt Peale painted a life portrait of George Washington during the president’s second term. This rare opportunity had been arranged by Rembrandt’s father, Charles Willson Peale, who had already painted Washington from life more often than any other artist. While the elder Peale painted beside him (“to calm my nerves”), Rembrandt created a rivetingly realistic head of the president. [1] For the sittings with Washington, the Peales alternated with portraitist Gilbert Stuart—the Peales painted Washington one day and Stuart, the next.

The younger Peale was never fully satisfied with his resulting life portrait, though he soon produced 10 copies from it. The intention behind the sittings had been, in fact, to supply the young artist with a model that could serve for future replicas. But unlike Stuart, who painted his “Athenaeum” head of Washington the following year and replicated it more than 70 times, Rembrandt Peale soon stopped copying his life study.

A quarter century after the 1795 effort, Peale set out to create a new portrait of Washington that would show his “mild, thoughtful & dignified, yet firm and energetic Countenance.” In his privately printed essay, “Lecture on Washington and his Portraits,” the artist recounted “repeated attempts to fix on Canvass the Image which was so strong in my mind, by an effort of combination, chiefly of my father’s and my own studies.” [2] Visits to France (1808–10) had exposed him to the neoclassical style then fashionable in Paris, and these ideals thenceforth competed with the innate realism that informed his earlier work. In 1823, following the highly successful tour of his huge allegorical painting, The Court of Death, Peale began contemplating a new project: an image of George Washington that would, he hoped, become the “Standard likeness” of the first president. [3] To realize this likeness—to invent it, really—he reviewed paintings of Washington by John Trumbull, by Gilbert Stuart, and, of course, by his own father, as well as the famous sculptural portrait by Jean-Antoine Houdon. This last he considered the finest of all portraits of Washington, an opinion still widely held. Peale decided that a composite of the best likenesses was most likely to result in the icon he hoped to produce.

Confining himself to his studio for three months, he painted in a “Poetic frenzy.” [4] When completed, the portrait was given the blessing of the elder Peale, who, Rembrandt reported, judged it the best he had ever seen. Rembrandt Peale had invented a composition that presented the hero in a symbolic manner, blending portraiture with history painting. He settled on a format roughly twice the size of a standard portrait, within which he painted a strikingly illusionistic stone oval window atop a stone sill engraved with the legend “PATRIAE PATER” (Father of His Country). The window is decorated with a garland of oak leaves, and it is surmounted by the “Phydian head of Jupiter” (Peale’s description) on the keystone. The oak was sacred to Jupiter, and it also had a long Christian tradition as a symbol of virtue and endurance in the face of adversity. Within this “porthole,” as it was soon dubbed, Peale placed the bust-length figure of Washington with an extraterrestrial background of clouds and shadows. Not just a simple sky, it has the effect of placing Washington, if not precisely in eternity, then (in Thomas Jefferson’s words) in “everlasting remembrance.” [5]

Peale’s extraordinarily difficult problem had been how to use the best sources to reinvent an image of Washington that could mediate among them. He stated publicly that he had based the new image on his 1795 portrait, his father’s portraits, and Houdon’s portrait. Rembrandt was flattering his father: Only the last of the elder Peale’s seven different likenesses of Washington, painted beside his son in 1795, has any similarity to Rembrandt’s work, and then perhaps mainly in the elegant ruffled shirt. In fact, Rembrandt scarcely consulted his own youthful effort. It was the Houdon of 1785 that prevailed, and this was the most appropriate source, because it showed a still-vigorous Washington in retirement after the War of Independence but before the rigors of the Constitutional Convention and his presidential service. This revivified heroic Washington is firmly linked to the real world by his black cloak, which tumbles out of the window onto the sill, while the hero himself remains in the ethereal space behind it.

But Peale’s neoclassical idealism went further than Houdon’s, and he subjected Washington’s features to what one writer has called “a puffy articulation of the planes of the face,” a stylization that suggests pinches of modeling clay. [6] At the same time, the idiosyncratic particulars that marked Houdon’s rendering of such passages as eyebrows, the bridge of the nose, and hair are erased or superseded by regularity, and the head is bathed in a strong light that glosses the features with the sheen of perfection. Washington’s nose is made still more Roman and, indeed, it invites comparison with the nose of Jupiter above, which in turn reminds viewers of Washington’s godlike status in the hearts of his countrymen. The result is an undeniably forceful presence, not Washington exactly, but the idea of Washington.

“Mild, yet resolute” was Chief Justice John Marshall’s summation of the likeness–and it does possess immense dignity and venerable nobility. [7] It manages to belong to two realms, the reality of the fictive stone framework in front of Washington and the timeless world behind him. Finally, and very significantly, it should be recalled that the “invention” of the porthole portrait was, in fact, an inspiration borrowed from ancient Rome, for it is in Roman funerary sculpture that the portrait of the deceased is so framed. Though not the only painter to borrow this device, Peale demonstrated that it was doubly appropriate for Washington. It was fitting, first, for a posthumous portrait, and second, as an allusion to the Roman Republic, whose ideals were continually invoked by the Founding Fathers.

Peale painted the Senate picture and the first replica of it almost simultaneously, in Philadelphia during the winter of 1823–24. In late February 1824, he put the original painting on display in the U.S. Capitol. There it was viewed by members of Congress and many of Washington’s friends and relatives. The porthole portrait of Washington did not become the “standard likeness,” but it became second only to the image by Gilbert Stuart, which proved impossible to displace from the public imagination. Of Peale’s nearly 80 replicas or variants, the version in the Senate is the masterpiece. No painting in the U.S. Capitol has greater historical or symbolic resonance.

The artist collected testimonials from more than 20 individuals who had known Washington; he later published them in a pamphlet titled Portrait of Washington. The comments praised the painting and include such glowing descriptions as those of Chief Justice John Marshall: “The likeness in features is striking, and the Character of the whole face is preserved & exhibited with wonderful Accuracy. It is more Washington himself than any Portrait of him I have ever seen.” [8] Peale used the resulting publicity to lobby Congress, unsuccessfully, for a commission to paint an equestrian portrait of General Washington.

Peale then exhibited his Patriæ Pater portrait in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. In the spring of 1827, he drew a lithograph based on the painting, in the Boston studio of William and John Pendleton, whose lithographic press was highly regarded. The lithograph was awarded a silver medal, the highest award, at the fall exhibition at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. This and other images based on the painting ensured widespread recognition. Late in 1828 Peale sailed for Europe, where he remained until September 1830, taking Patriæ Pater with him. He reported that the painting was well received in Rome, Naples, Paris, and London. In Florence it was exhibited at the Accademia in September 1829 and praised by the press.

Congress, though reluctant to spend money on art in the early years of the nation, was prompted by the 1832 centennial of George Washington’s birth to purchase Patriæ Pater from Rembrandt Peale for $2,000. After its purchase, the painting was hung at the gallery level in the Senate Chamber, where it remained until the Senate moved into its new north wing Chamber in 1859, and the Supreme Court moved upstairs into the Old Senate Chamber. At that time, the painting was moved to the new Vice President’s Room near the Senate floor. It remained there until the restoration of the Old Senate Chamber as a museum room in 1976, allowing the return of the portrait to its original location.

The oil replicas of Peale’s original porthole portrait of Washington constitute four distinct categories: those identical to the original, with the subject’s face turned proper right and featuring civilian dress; those similar to the original, but with face turned to the left; those with Washington’s face turned right, but featuring military dress; and those facing left, with military dress. The example at the Pennsylvania Academy is believed to be the original of the second type. The New-York Historical Society owns a late 1853 version in which Washington wears a military uniform. Peale justified the many replicas by claiming that, because he was the last living artist to have painted Washington from life, “the reduplication of...[my] work, by...[my] own hand, should be esteemed the most reliable.” [9]

1. John Hill Morgan and Mantle Fielding, The Life Portraits of Washington and Their Replicas (Lancaster, PA: Lancaster Press, 1931), 369.

2. Gustavus A. Eisen, Portraits of Washington, vol. 1 (New York: Robert Hamilton, 1932), 312.

3. Lillian B. Miller and Carol Eaton Hevner, In Pursuit of Fame: Rembrandt Peale, 1778-1860 (Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1992), 144.

4. Eisen, 313.

5. Thomas Jefferson, The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Adrienne Koch and William Peden (1944; reprint, New York: Modern Library, 1993), 174.

6. Carol Eaton Hevner and Lillian B. Miller, Rembrandt Peale, 1778–1860: A Life in the Arts. An Exhibition at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, February 22, 1985 to June 28, 1985 (Philadelphia: The Society, 1985), 25.

7. Ibid., 66.

8. Eisen, 315.

9. Rembrandt Peale, Portrait of Washington (Philadelphia: n.p., 1824?), 2.

George Washington, first president of the United States, earned the epithet Father of His Country for his great leadership, both in the fight for independence and in unifying the new nation under a central government. Washington was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, and worked as a surveyor in his youth. In 1752 he inherited a family estate, Mount Vernon, upon the death of a half brother, Lawrence. Washington's military career began in 1753, when he accepted an appointment to carry a warning to French forces who had pushed into British territory in the Ohio valley. In subsequent military assignments, Washington distinguished himself against the French, first while aiding General Edward Braddock and later as commander-in-chief of all Virginia militia.

In 1758 Washington returned to civilian life as a gentleman-farmer at Mount Vernon and soon took a seat in the Virginia house of burgesses. As a planter, Washington had firsthand knowledge of the economic restrictions being imposed by Britain, and as a Virginia legislator, he supported political efforts to curtail British control of the colonies. Washington was selected to serve as a delegate to the first and second Continental Congresses, and in June 1775 he was chosen to command the American forces. He successfully led the Continental army through eight difficult years of war for independence.

In 1783, after the Revolution, Washington resigned his military commission to Congress at Annapolis, Maryland. Recognizing the need for a strong central government, he served as president of the federal convention charged with drafting the Constitution. Reluctantly, he accepted the will of his colleagues to become president of the new nation, and he was inaugurated in New York City on April 30, 1789. Contending with the ideological struggles within the government, and with hostilities between France and Great Britain, Washington greatly feared the growth of political parties and the dangers of foreign involvement. These issues impelled him to serve a second term as president.

His attempts to solve foreign relations issues during his second term resulted in Jay's Treaty (1794), a vain attempt to regulate trade and settle boundary disputes with Great Britain, and the Pinckney Treaty (1795), which successfully settled such issues with Spain. Washington also acted vigorously to enforce federal authority by quashing the Whiskey Rebellion, during which liquor producers in western Pennsylvania threatened the new republic by rebelling against an unpopular excise tax on whiskey.

Washington's 1796 Farewell Address to the nation emphasized the need for a unified federal government and warned against party faction and foreign influence. Although often subjected to harsh criticism by his contemporaries, Washington succeeded in giving the new government dignity. He saw a federal financial system firmly established through the efforts of Alexander Hamilton, and he set valuable precedents in the conduct of the executive office. Washington retired to Mount Vernon, where he died on December 14, 1799.