| 202602 12Edward Brooke of Massachusetts—The Bridge Builder

February 12, 2026

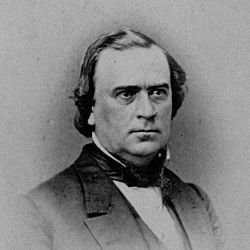

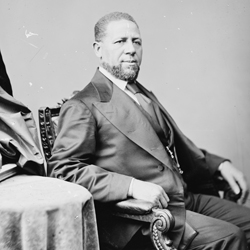

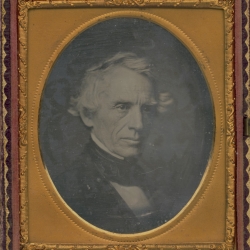

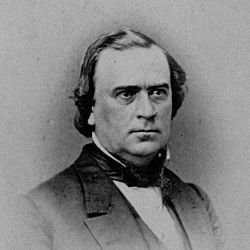

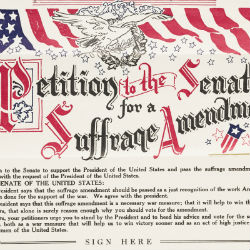

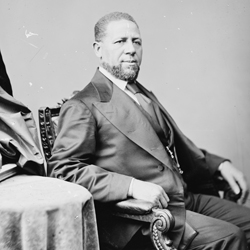

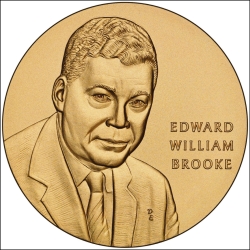

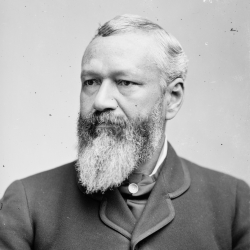

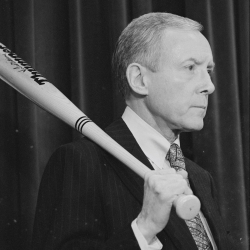

In 2009 former Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the first popularly elected African American senator, received the Congressional Gold Medal in recognition of his “pioneering accomplishments” in public service. During his two Senate terms, Brooke had been a pragmatic lawmaker, building bridges across party and racial lines to chart a course out of the nation’s segregated past, earning his place in the ranks of civil rights pioneers.

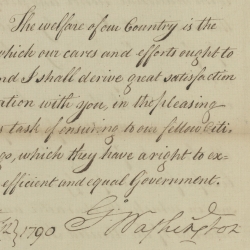

On October 28, 2009, former Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the first popularly elected African American senator, stood in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda to receive the Congressional Gold Medal. It was fitting that President Barack Obama, the first African American elected to the presidency, presented the medal to Brooke. Obama highlighted the improbability of a Black, Protestant Republican winning office in a state known for being white, Catholic, and Democratic. As Obama recalled, Brooke “ran for office, as he put it, to bring people together who had never been together before, and that he did.” As the only African American to serve in the Senate during the civil rights era, Brooke brought a unique set of experiences and perspectives to bear on some of the most politically charged issues of his time.1

Edward Brooke was born in the District of Columbia in 1919, to Helen, a homemaker, and Edward Jr., a lawyer with the U.S. Veteran’s Administration. Brooke grew up in the Brookland neighborhood of northeastern D.C., at a time when the city’s schools and public accommodations were segregated. He attended Dunbar High School, one of the best performing public high schools for African American students in the country. Following in his father’s footsteps, Brooke enrolled at Howard University, where he served in the school’s ROTC program, graduating in June 1941. Brooke entered the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant with the segregated, all-Black 366th Combat Infantry Regiment stationed at Fort Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts, on December 7, the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. 2

Brooke’s army service was an eye-opening, transformative experience. On the army base in Massachusetts, African American men were denied access to the pools, the exchange, and the officers’ club. “We were treated as second-class soldiers,” Brooke later recalled. Despite lacking any legal training, Brooke successfully defended Black enlisted men in military court—an experience that later led him to law school. In 1944 he sailed with his unit to Europe where he served in North Africa and in the campaign to liberate Italy. Brooke continued to encounter discrimination on base, this time in the form of racist tirades from his commanding officers. With some basic language training, Brooke quickly developed a fluency in Italian, a skill that proved useful in reconnaissance missions with Italian partisans. “My principal job,” he later explained, “was to map mine fields, supply roads, ammunition dumps, to locate concentration camps, and take prisoners for interrogation.” He never forgot the contrast between the freedom and dignity he felt when off base and the racism he experienced on base. Despite the challenges, Brooke earned the rank of captain and was awarded a Bronze Star in 1943 for “heroic or meritorious achievement or service.” While stationed in Italy, he met Remigia Ferrari-Scacco and the two were married in Boston in June 1947.3

Upon his return stateside, Brooke enrolled in Boston University School of Law, earning both a bachelor and a master of laws degree in 1948 and 1950, respectively. He built his own firm in Roxbury, a predominantly African American Boston neighborhood. Encouraged by friends to run for a seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the political neophyte (he did not cast his first vote until age 30) entered both the Republican and Democratic primaries for the house seat in 1950. He won the G.O.P. nomination but lost the general election. He ran again in 1952, with the same result. Stinging from two successive electoral defeats, Brooke continued to practice law while volunteering with various civic organizations, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.4

In 1960 state Republicans urged Brooke to run for secretary of the Commonwealth. He lost the race by a narrow margin to Democrat Kevin White, whose barely disguised racially charged slogan was, “Vote White.” Impressed by Brooke’s strong showing, Republican Governor John Volpe invited him to join his staff. Brooke declined but asked to be appointed chair of the Boston Finance Commission, a municipal watchdog. Volpe obliged, and Brooke transformed the moribund commission into an anti-corruption force, overseeing dozens of investigations, some of which resulted in the resignation of city officials. His oversight work helped him win election as state attorney general in 1962, flipping the office for the GOP. His victory made him the first African American attorney general in the nation and the highest-ranking African American in any state government at the time.5

Three years later, Brooke set his sights on national office. When Republican Senator Leverett Saltonstall announced his retirement in December 1965, Brooke jumped into the race for the open seat. His opponent was former Governor Endicott Peabody, who enjoyed the endorsement of Massachusetts’s popular senator, Democrat Edward “Ted” Kennedy. Brooke won handily, claiming 60 percent of votes cast. Members of the Black press hailed this historic victory as “the most exciting step forward for the Negro in politics” since Reconstruction.6

As an elected official in Massachusetts, Brooke had always been mindful that fewer than 10 percent of his constituents were Black. As attorney general, he had once declared, “I am not a civil rights leader and I don’t profess to be one. I can’t just serve the Negro cause. I’ve got to serve all the people of Massachusetts.” Even so, as the Senate’s only Black member during the peak of the civil rights movement, Brooke was committed to combating racial discrimination, noting in February 1967, “It’s not purely a Negro problem. It’s a social and economic problem—an American problem.”7

To tackle this problem, Brooke worked across party lines. He co-sponsored the Fair Housing Act with Democratic Senator Walter Mondale of Minnesota. Informed by Brooke’s work on the President’s Commission on Civil Disorders, the bill would prohibit housing discrimination in the sale, rental, or financing of housing nationwide. This would become the key provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Passing this ambitious civil rights bill, which faced strong opposition from southern senators, required patience and political acumen. At a time when it took two-thirds of senators present and voting to invoke cloture and overcome a filibuster, Brooke and Mondale painstakingly built a bipartisan coalition to pass the bill. After weeks of debate, and three failed cloture motions, the Senate finally invoked cloture and approved the bill. Brooke stood by the side of President Lyndon B. Johnson on April 11, 1968, as he signed it into law.8

Senator Brooke’s pragmatic approach to politics did not change after Republican Richard Nixon gained the presidency in 1969. While Brooke often supported the administration’s policies, including official recognition of China and nuclear arms limitation, he did not refrain from expressing his differences. He opposed three of the president’s six Supreme Court nominees, citing concerns over their stances on segregation. In November 1973, after the Senate Watergate Committee revealed that the Nixon administration had orchestrated a cover-up of its illegal campaign activities, Brooke became the first Republican senator to publicly call for the president’s resignation. “It has been like a nightmare,” Brooke said. “He might not be guilty of any impeachable offense “[but] because he has lost the confidence of the people of the country … he should step down, should, tender his resignation.”9

During the 1970s, much of Brooke’s legislative attention turned to protecting school desegregation efforts. Stating on national television that he was “deeply concerned about the lack of commitment to equal opportunities for all people,” Brooke charged that the White House neglected Black communities by failing to enforce school integration. Brooke was also central in defeating several antibusing bills initially passed by the House. In 1974 he successfully defeated the Holt amendment to an appropriations bill, introduced by Maryland Representative Marjorie Sewell Holt, that would have effectively ended the federal government’s role in school desegregation. That same year, Brooke helped quash an amendment introduced by Senator Edward Gurney (R-FL) that similarly would have ended busing. In 1975 Brooke reaffirmed his support for busing programs despite the political risk. “It’s not popular—certainly among my constituents. I know that,” he explained. “But, you know, I’ve always believed that those of us who serve in public life have a responsibility to inform and provide leadership for our constituents.”10

Brooke focused on other legislative initiatives as well, including regulating the tobacco industry, providing funding for cancer research programs, investigating connections between civil unrest and poverty, and advocating for a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion.11

Brooke easily won reelection in 1972 but faced a serious primary challenge in 1978, narrowly defeating conservative radio host and political newcomer Avi Nelson. Politically damaged by charges of financial improprieties, he was ultimately defeated by Democrat Paul Tsongas in the general election. Brooke retired from politics to practice law in Washington, D.C. In 2004 President George W. Bush awarded Brooke the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Four years later, Congress awarded him the Congressional Gold Medal, making him just the seventh senator to receive the award at the time. He died in January 2015.12

Edward Brooke did not define himself as a civil rights leader, but as a self-professed “creative Republican” and the Senate’s lone Black member, he sought ways to fight racial discrimination and improve opportunities for African Americans. Brooke was a pragmatic lawmaker, building bridges across party and racial lines to chart a course out of the nation’s segregated past, earning his place in the ranks of civil rights pioneers.13

Notes

1. Martin Kady II, “Brooke gets Congressional Gold Medal,” Politico, October 29, 2009, https://www.politico.com/story/2009/10/brooke-gets-congressional-gold-medal-028864.

2. “An Individual Who Happens to be a Negro,” Time, February 17, 1967.

3. Edward Brooke, Bridging the Divide (Rutgers University Press, 2007), 22.; John Henry Cutler, Ed Brooke; Biography of a Senator (Bobs Merrill, 1972), 27; “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE, Edward William, III,” History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, accessed February 3, 2026, https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/B/BROOKE,-Edward-William,-III-(B000871)/.

4. “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives; Brooke, Bridging, 64.

5. “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives.

6. Edward W. Brooke, The Challenge of Change: Crisis in Our Two-Party System (Boston: Little, Brown, 1966); David S. Broder special, “Saltonstall is Quitting Senate,” New York Times, December 30, 1965; “Brooke Takes Office as Mass. Attorney General,” Chicago Defender, January 17, 1963, 4; “Brooke Takes a Giant Step into National Prominence,” Boston Globe, November 11, 1966, 18; “An Individual,” Time.

7. “Edward W. Brooke, Former U.S. Senator, Oaks Bluff Resident, Dies at 95,” Martha’s Vineyard Times, January 3, 2015, https://www.mvtimes.com/2015/01/03/edward-w-brooke-former-u-s-senator-oak-bluffs-resident-dies-95/; “An Individual,” Time.

8. Rigel C. Oliveri, “The Legislative Battle for the Fair Housing Act (1966–1968),” in Gregory D. Squires, ed., The Fight for Fair Housing: Causes, Consequences and Future Implications of the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act (New York: Routledge, 2017); “Congress Passes Rights Bill: Bars Bias in 80% of Housing,” Boston Globe, April 11, 1968, 1; “President Signs Civil Rights Bill: Pleads for Calm,” New York Times, April 12, 1968, 1; Civil Rights Act of 1968, Title VIII, Fair Housing, Public Law 90-284, 82 Stat. 73 (1968).

9. Brooke, Bridging, 191, 202, 203–4; “A Portrait of Racism,” Boston Globe, February 8, 1970, A25; “Brooke to Vote Against Nominee,” Hartford Courant, February 26, 1970, 5; “GOP Senator Brooke Asks Nixon to Quit,” Atlanta Constitution, November 5, 1973, 1A; “Carswell Disavows ’48 Speech Backing White Supremacy,” New York Times, January 22, 1970.

10. “Brooke Says Nixon Shuns Black Needs,” New York Times, March 12, 1970; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives; Richard D. Lyons, “Busing of Pupils Upheld in a Senate Vote of 47-46,” New York Times, May 16, 1974; Jason Sokol, “How a Young Joe Biden Turned Liberals Against Integration,” Politico, August 4, 2015, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/08/04/joe-biden-integration-school-busing-120968/.

11. Brooke, Bridging, 186, 216–7, 220.

12. Dane Morris Netherton, “Paul Tsongas and the Battles Over Energy and the Environment, 1974-80,” Ph.D. diss., Washington State University (May 2004): 130, 144.; “U.S. Senators Awarded the Congressional Gold Medal,” United States Senate, accessed February 3, 2026, https://www.senate.gov/senators/Senators_Congressional_Gold_Medal.htm.

13. Gary Orfield, “Senator Edward Brooke: A Personal Reflection,” The Civil Rights Project, accessed January 8, 2015, https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/senator-edward-brooke-a-personal-reflection-by-gary-orfield/; Sally Jacobs, “The Unfinished Chapter,” Globe Magazine, March 5, 2000, https://cache.boston.com/globe/magazine/2000/3-5/featurestory2.shtml.

|

| 202512 16Square 686: A Capitol Hill Neighborhood Transformed

December 16, 2025

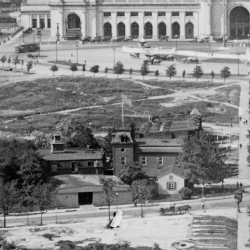

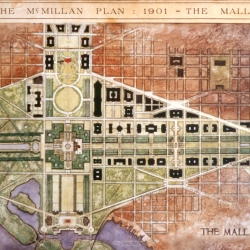

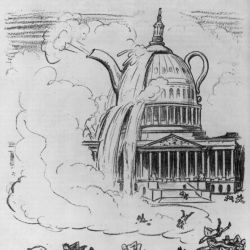

At the turn of the 20th century, the blocks around the Capitol were a hub of activity, similar to today, but the landscape was quite different. The office buildings, parks, fountains, and monuments we see today were once densely populated neighborhoods of apartment buildings, row houses, businesses, and store fronts. Between 1900 and 1910, Congress’s growing need for space led to the transformation of neighborhoods around the Capitol, including Square 686, a city block just north of the Capitol.

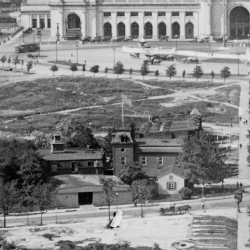

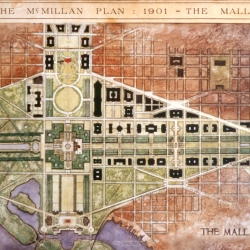

Today, the blocks around the Capitol hum with the movement of tourists, Capitol Hill residents, and members of Congress, their staff, and visitors. Office buildings, parks, fountains, and monuments line the streets, interspersed with row houses and various associations and businesses. At the turn of the 20th century, this land was also a hub of activity, but with many key differences. The densely populated neighborhoods then consisted mostly of apartment buildings, row houses, hotels, hospitals, businesses, store fronts, and churches. Between 1900 and 1910, developers began the transformation of the landscape around the Capitol. To its east, the Pennsylvania Railroad cut and bore a new tunnel directly underneath 1st Street fronting the Library of Congress. Several blocks to the north, planning for a new train terminal, called Union Station, was well underway. To the south, the House’s new office building swallowed an entire city block. And just north of the Capitol, the Senate acquired the thriving city block designated Square 686 and constructed its first office building. 1

The new Senate Office Building was designed to address a critical need. Between 1850 and 1900, 14 states joined the Union, adding 28 senators to a building that was designed to meet the needs of fewer people. The Senate expanded its clerical staff during the same period, in part to support its growing workload, but there was limited workspace for them. Most senators conducted business at their desks in the Senate Chamber. Those who chaired committees gained the use of the Capitol’s larger rooms, which doubled as the chairman’s personal office and accommodated committee staff. These conditions forced senators and staff to use any available space in the Capitol, including alcoves in the attic, corners in the basement, and converted storerooms and closets. In desperation, some senators rented their own office space in nearby buildings. The Senate acquired the Maltby Building—a five-story apartment building located where the modern Taft Carillon now stands—in 1891, but it was not well-maintained. In early 1904, an inspection by Superintendent of the Capitol Elliott Woods identified structural flaws rendering the Maltby Building “extremely hazardous” and “not suited to the uses to which it is now put.”2

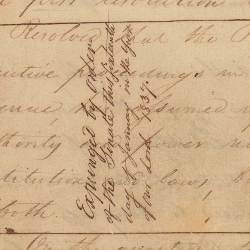

By 1902 both the Senate and House had publicly acknowledged intentions to construct office buildings “at no distant day.” The House moved more quickly than the Senate. The Civil Appropriations Act that passed on March 3, 1903, included a $750,000 appropriation to initiate House Office Building excavations. The next year’s appropriation bill, authorized on April 28, 1904, set aside $750,000 for land purchases and $2.25 million for the construction of a Senate office building. The appropriation passed with wide support by a vote of 50-10. Just before the vote, Senator William Stewart of Nevada stated on the Senate floor he was “heartily in favor of the new building … though I shall not be here to enjoy it” due to his pending retirement. Senator William Stone of Missouri acknowledged that only some senators “have excellent quarters in the Capitol … their surroundings are pleasant, congenial, and conducive to good thought and to good work.” In Senator Stone's opinion, a new office building would provide “a nearer approach to equality in the accommodations afforded senators.” Some senators worried about the public perception of this expense. Senator James Berry of Arkansas opposed the measure. “I believe it is wrong,” Berry stated. “I believe it is extravagant … and I believe that if we pass a bill here appropriating money to build offices and committee rooms for the Senate, costing even $33,000 for every Senator here, it will tend to give color to the charge of extravagance which has so often been made against this body.”3

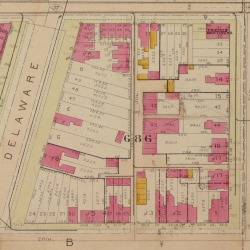

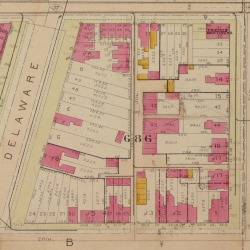

With funding secured, the Senate formed the Senate Building Commission and selected Senators Shelby Cullom of Illinois, Jacob Gallinger of New Hampshire, and Francis Cockrell of Missouri to direct all expenditures, land acquisition, and building construction. They worked closely with Architect of the Capitol Elliott Woods and consulting architect John Carrère of the private firm Carrère and Hastings to develop building designs mirroring those of the new House Office Building. Planners had long decided on Square 686 to the north of the Capitol as the location for the new building. Bounded by B Street, C Street, 1st Street, and Delaware Avenue, Northeast, this block created symmetry with the location of the corresponding House building on the other side of the Capitol. In May 1904 the committee and Woods named Samuel Bieber, a Washington, DC-based banker and real estate expert, to establish price estimates and lead negotiations for land acquisition. In July 1904, when the commission conducted its initial land and title surveys, Square 686 consisted of 45 parcels with 178 owners possessing some financial stake.4

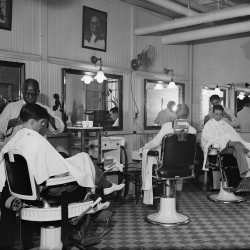

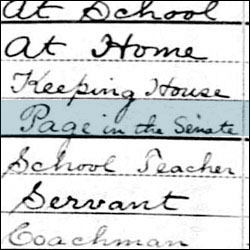

Square 686 was a typical Capitol Hill community. First divided into lots in 1799, people began constructing houses immediately thereafter. An alleyway—Orial Court—bifurcated the square from north to south. According to the 1900 U.S. Census, 300 individuals lived within Square 686, with 252, or 84 percent, renting their homes. Occupants included a cross-section of everyday DC life, such as railroad worker Albert Cox (246 Orial Court), chief of the U.S. Consular Bureau of the State Department and Consul to Canada Robert Chilton, Jr. (225 Delaware Avenue), and Treasury Department clerk Sallie Boaz (48 B Street). At the corner of First and C Streets, the Baltimore Yearly Meeting of Friends, one of the oldest Quaker organizations in America, operated a meeting house. At the center of the block on Delaware Avenue was Casualty Hospital serving the city’s poor. The block was also home to stenographers, bookbinders, teachers, policemen, butchers, masons, speculators, and dairy workers.5

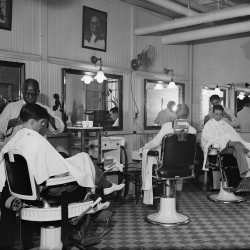

Orial Court in Square 686 was similar to other alleyways found throughout DC during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Photographer Godfrey Frankel captured images of many of these in the 1940s, revealing dilapidated structures and crowded conditions. Yet residents developed strong community and family bonds and considered these alleyways home. While photographs of Orial Court have yet to be located, insurance maps suggest the alley, measuring 15 feet across, had 20 residences. According to the 1900 Census, 88 people lived in the court, predominantly African Americans. In comparison, just one household on the perimeter of the square was headed by an African American individual. The 1900 Census also recorded more than one household within each Orial Court structure, though the census recorded the same pattern in houses on the perimeter. Comparing employment, however, reveals significant differences. Residents of homes on the perimeter of 686 worked in a variety of professions; those calling Orial Court home overwhelmingly worked as domestic help (e.g., “houseworker,” “washerwoman,” “servant”) or as laborers (e.g., “laborer railroad,” “driver lumber,” “whitewasher”).6

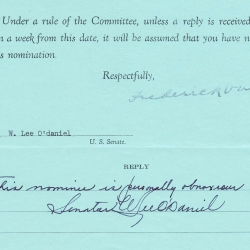

Senate-appointed negotiator Samuel Bieber met with Square 686 property owners throughout May 1904. The Washington Post reported on May 1, 1904, that the square’s 45 parcels assessed at “considerably less than $300,000,” so the Senate Building Commission hoped all parcels could be acquired quickly given the $750,000 appropriation. A few weeks later, the commission met to hear updates on Bieber’s negotiations. The Evening Star reported that Bieber’s negotiated prices were “far in excess of the assessed value of the property.” Exactly what those prices were remains unclear, but with Senator Gallinger out of town, Senators Cullom and Cockrell quickly determined “that it was not in the advantage of the government to accept any of the offers” and ordered the architect of the Capitol to proceed with condemnation, a legal process more popularly known as “eminent domain” by which the government purchases private land for public use at a price usually negotiated by a third party, such as an arbitrator or judge.7

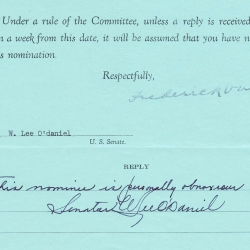

In August 1904, the Square 686 condemnation proceedings began. Representatives for the 178 parcel owners and the government’s attorneys appeared in the District of Columbia Supreme Court to negotiate. Following congressional guidance, the court created a three-person committee to navigate the complex condemnation process and appointed three “prominent citizens of the District,” all wealthy men: Robert I. Fleming (architect and member of the D.C. Board of Commissioners), James F. Oyster (businessman and civic leader), and H. Rozier Dulaney (real estate agent). Throughout August and September, they toured Square 686 and held hearings to receive testimony from parcel owners. Their report, submitted in October 1904, identified 45 sale agreements totaling $746,111. The Senate Building Commission quickly approved the report, and funds were then distributed in December. All residents, including both owners and renters, vacated Square 686 by January 1905.8

Only one recorded instance survives of pushback from a Square 686 resident. W. H. Smith, a tenant living on the third floor of 28 B Street NE petitioned the court on August 9, 1904, that “by means of the condemnation and purchase of the square by the Federal Government, he will be forced to vacate the premises which he has peaceably and satisfactorily occupied as stated, subjecting him to both trouble and expense, with little or no hope of finding another apartment that will be as convenient or comfortable.” Smith, a Government Printing Office employee, claimed $500 to account for potential damage to furniture and moving costs. Surviving records do not indicate whether Smith received payment, though by 1906 he was residing in a rental unit south of the Capitol on New Jersey Avenue SE, directly across the street from the construction of the new House Office Building.9

Following the condemnation proceedings, at least one Square 686 parcel owner—Casualty Hospital—seemed to welcome the change. The hospital building, a three-story brick converted residence, was woefully insufficient according to the hospital’s board of directors. During the first three months of 1904, for example, hospital staff treated nearly 5,000 individuals, including 411 emergency cases and 115 surgeries within what The Evening Star described as “the present ancient structure.” The same article reported that directors desired “a modern hospital fitted out with the latest medical and surgical appliances, and an ambulance … [given] the necessity for such an establishment … in the eastern part of the city.” Within a year, Casualty Hospital reopened in a newly renovated facility six blocks to the east on Massachusetts Avenue, NE. Other parcel owners successfully relocated as well. Even though the Baltimore Yearly Meeting of Friends had just spent $2,000 in February 1904 to upgrade to their auditorium with a new floor, brick repairs, and a gallery extension, the group used the $21,800 received from condemnation to move to Columbia Heights in 1905.10

By the summer of 1905, Square 686 had been reduced to rubble, dirt, and a “dinkie railroad”—a short temporary locomotive line—that carried refuse north to the future site of Union Station. The once vibrant community of private residences and businesses would soon be replaced by the Senate Office Building, which opened in 1909, and the accompanying hustle and bustle of senators, staff, and visitors. Other construction projects followed over the next 70 years as the Senate cleared additional land to make way for new parks, monuments, and office buildings. These developments altered the Capitol Hill landscape to support the critical work of the United States Senate.11

Notes

1. “Cannon House Office Building,” Architect of the Capitol, accessed December 5, 2025, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/buildings-grounds/house-office-buildings/cannon; Thomas S. Hines, Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner (University of Chicago Press, 2009), 284–8; Building Conservation Associates, “Washington Union Station Historic Preservation Plan: Volume I” (2015), 22, accessed December 5, 2025, https://www.usrcdc.com/projects/historic-preservation-plan/; “Opposed to Open Cut,” Washington Post, March 3, 1905.

2. “Maltby Building,” U.S. Senate Historical Office, accessed December 5, 2025, https://www.senate.gov/about/historic-buildings-spaces/office-buildings/maltby-building.htm.

3. Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia, S. Rep. 57-166, 57th Cong., 1st sess., January 15, 1902; Shelby M. Cullom, Fifty Years of Public Service (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1911), 347–8; Henry A. Converse, “The Life and Services of Shelby M. Cullom” in Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society for the Year 1914 (Illinois State Historical Library, 1914); “For House Offices and Extension to Capitol,” Washington Times, February 12, 1903; “Consult Engineers on Office Building Site,” Washington Times, March 7, 1903; “The House Office Building Criticized,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 16, 1903; ”Waiting for Titles,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), June 11, 1903; “Is Not Privileged,” Evening Star, April 27, 1904; “An Office Building,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 21, 1904; Congressional Record, 58th Cong., 2nd sess., April 19, 1904, 5083–4, 5170–1; William C. Allen, History of the United States Capitol (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 378–81.

4. “Office Building for the Senate,” Washington Times, April 15 1904; “Dolliver Talks About the Trusts,” Age-Herald (Birmingham, AL), April 21, 1904; “Real Estate Market,” Washington Post, May 1, 1904; “Extension of the Capitol,” Baltimore Sun, May 1, 1904; “Mr. Bieber Named,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), May 4, 1904; “District Dock. 2, No. 624,” July 18, 1904, Case 624, Box 55, District Court Case Files Relating to Admiralty and Condemnation Proceedings, Record Group 21: Records of the District Courts of the United States, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

5. Population Schedule for Washington, D.C., Enumeration District No. 118, Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900, Record Group 29: Records of the Bureau of the Census, Microfilm Publication T623, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC; Robert S. Chilton Papers 1, finding aid, Georgetown University Library Booth Family Center for Special Collections, accessed December 5, 2025, https://findingaids.library.georgetown.edu/repositories/15/resources/10018.

6. Godfrey Frankel, In the Alleys: Kids in the Shadow of the Capitol (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995); Population Schedule for Washington, D.C., Enumeration District No. 118; George William Baist, Baist's Real Estate Atlas of Surveys of Washington, District of Columbia: Complete in Four Volumes, 1913, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

7. “Real Estate Market,” Washington Post, May 1, 1904; Susan Mandel, “The Lincoln Conspirator,” Washington Post, February 3, 2008; “Price Regarded as High,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), May 25, 1904.

8. “Court Acts Upon Senate Building Site,” Washington Times, August 10, 1904; “Preliminary Steps,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 10, 1904; “Commission Named,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 11, 1904; “District Court,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 12, 1904; “Hearing of Testimony,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 22, 1904; Robert Isaac Fleming Papers, Finding Aid, The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., accessed December 5, 2025, https://dchistory.catalogaccess.com/archives/104088; “District Dock. 2, No. 624,” “Certificate of Publication”; “Senate Office Site,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 12, 1904; “The Award Approved,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 22, 1904; “In the District,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 22, 1904; “Distributing Funds to Pay for Site,” Washington Times, December 27, 1904.

9. “District Dock. 2, No. 624,” W. H. Smith to Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, August 9, 1904, December 5, 1904; Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia (Washington D.C.: R.L. Polk & Co., 1903); 895; Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia (Washington D.C.: R.L. Polk & Co., 1906), 1043.

10. “Casualty Hospital Report,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 23, 1904; “Capitol Hill Historic District (1976 Boundary Increase),” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, January 26, 1976, D.C. Office of Planning, accessed December 5, 2025, https://planning.dc.gov/publication/capitol-hill-historic-district; “Permit No. 1136,” Feb. 11 to Mar. 8, 1904, Permits 1135 – 1251, Record Group 351: Records of the Government of the District of Columbia, Series: Building Permits, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC; “St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church South,” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form:, November 30, 2017, D.C. Office of Planning, accessed December 5, 2025, https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/publication/attachments/St%20Pauls%20Methodist%20Episcopal%20Church%20South%20Nomination_1.pdf.

11. “Delay in the Work,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), December 1, 1904; “Excavations Begun,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), May 1, 1905.

|

| 202508 29Fifty Years of Preserving and Promoting Senate History

August 29, 2025

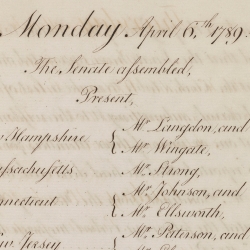

In May 1974, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and political historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., wrote a letter to Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield supporting a proposal to establish a Senate Historical Office. “The creation of such an Office would be of benefit,” Schlesinger wrote, “not only to historians and concerned citizens but to the Senate itself.” The next year, with the bipartisan blessing of Mansfield and Republican leader Hugh Scott, the Senate Historical Office was established on September 1, 1975.

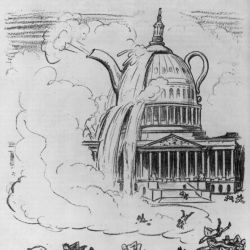

In May 1974, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and political historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., wrote a letter to Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield supporting a proposal to establish a Senate Historical Office. “The creation of such an Office would be of benefit,” Schlesinger wrote, “not only to historians and concerned citizens but to the Senate itself.” Schlesinger understood that the twin political crises of the 1970s—the Watergate scandal and the unpopular Vietnam War—had caused a growing number of Americans to lose faith in their institutions and to demand greater transparency from them. “If we are going to persuade the nation that Congress plays a role in the formation of national policy,” he wrote, “Congress will have to cooperate by providing the evidence for its contributions.” The next year, with the bipartisan blessing of Mansfield and Republican leader Hugh Scott, the Senate Historical Office was established on September 1, 1975.1

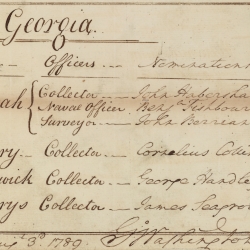

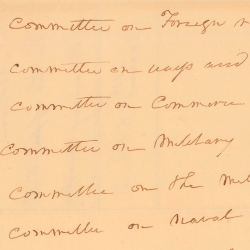

Tasked with overseeing the new office, Secretary of the Senate Francis Valeo articulated its mission. “Executive Branch departments and agencies have long had large historical offices and have long published or made public many of their important confidential papers,” Valeo explained in a letter to Senate appropriators justifying the creation of the new office. A Senate historical office would assist in the “organization of the Senate’s historic documentation,” serve as a “clearing house for public requests concerning historical subjects,” and “collect and preserve photographs depicting the history of the Senate.”2

Valeo hired Richard Baker to lead the new office. Baker brought a unique blend of skills and experience to the role. With degrees in history and library science, Baker had served as the Senate’s acting curator from 1969 to 1970 and then as vice president and director of research for the National Journal’s parent company. Former Washington Times staff photographer Arthur Scott filled the position of photo historian. Baker soon hired Leslie Prosterman as a research assistant and Donald Ritchie as a second historian.

Historians and newspapers heralded the office’s creation. “On behalf of the [American Historical] Association I want you to know how pleased we are that the Senate has established this new historical office,” wrote Mack Thompson, the organization’s executive director. “Much of the Senate’s business in the past was conducted in closed committee meetings,” noted Roll Call, leaving Senate records “locked away and forgotten,” resulting in the “history of significant public policy issues [being] written from the perspective of the Executive Branch where confidential records are generally declassified and published on a systematic basis.” The New York Times predicted that there would be much interest in the Senate’s “closed-door briefings on Pearl Harbor, the Cuban missile crisis, and the missile-gap controversy of the Eisenhower administration.” Generations of reporters, historians, and political scientists would come to rely upon the non-partisan expertise provided by Senate historians.3

One of the office’s most pressing early tasks was locating and arranging for the proper preservation of the Senate’s “forgotten” records. “Most senators in 1975 had given little thought to their papers,” recalled Baker in an oral history interview in 2010. Baker’s job was to persuade senators that selecting a repository for their papers was “prudent management practice … in the interest of public access.” There was much work to be done. Baker found humid attic and dank basement storerooms in the Russell Senate Office Building filled to overflowing with committee and member papers. A recent basement flood had destroyed 30 years of irreplaceable materials. Similarly, attic spaces, where temperatures soared in the summer and the prospect of a fire was not unthinkable, were ill-suited for safely preserving records. Racing the clock, Senate historians appraised collections and helped arrange for their long-term preservation. “Our major role is advisory,” Baker wrote during those early years. “We do not intend to build our own archives … [but to facilitate] the flow of archival materials to repositories where they will receive sufficient care and exposure.”4

The tidal wave election of November 1980 brought renewed urgency to Senate historians’ work. Eighteen departing senators had only a few months to vacate their offices. Some were leaving voluntarily, while others had been unexpectedly retired by their constituents. Historical Office staff scrambled to assist departing members—including Warren Magnuson of Washington State and Jacob Javits of New York, whose combined congressional service totaled 78 years—with moving their voluminous record collections to hastily designated repositories. Soon after that election, Baker hired Karen Paul as the Senate’s first archivist. Paul would devote the next 43 years of her career to advising senators, staff, and officers on the preservation and disposition of their records, developing archival policies and practices to ensure the preservation of Senate records for future generations, and building a community of professional Senate archivists.

Over the past five decades, the Senate Historical Office has built partnerships and institutional capacities to aid in the preservation of congressional records for the long term. Working with congressional leadership, the Historical Office helped to establish a separate division within the National Archives to serve as the official repository for congressional committee records in 1985—named the Center for Legislative Archives in 1988. In 1990 the Office co-founded the Advisory Committee on the Records of Congress to explore issues pertinent to congressional records management, and it co-created the Association of Centers for the Study of Congress in 2004, a nationwide consortium of congressional records repositories and research institutes. Today, Senate archivists continue to advance the Senate’s historical record by shaping how its documentation is preserved and accessed. They have developed and updated official records management policies and have pioneered digital preservation practices, creating workflows for archiving email, social media, and audiovisual records in line with national standards. Senate archivists also provide specialized staff training that equips members and support offices, as well as committees, to manage both paper and electronic records with confidence. The Historical Office also administers the Secretary of the Senate’s Preservation Partnership Grants that strengthen the capacity of repositories across the country to process and provide access to senators’ papers, broadening the range of materials available for research. This work safeguards the very documentation on which Senate history rests.

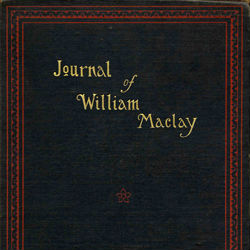

While preserved official records illuminate aspects of Senate history, they rarely tell the full story of an institution’s evolution. From the Historical Office’s earliest days, Senate historians have sought to document the social, cultural, and technological changes within the Senate with the Senate Oral History Project. Don Ritchie developed and led the project, with a mission to record and preserve the experiences of a diverse group of personalities—both staff and senators—who witnessed events firsthand and offer a unique perspective on Senate history. Interviews help to explain, for example, women’s evolving role in the Senate, and the impact of changing technology on the institution. There were no women senators serving in 1975, while 26 women serve in the 119th Congress. Only one senator’s office used a computer in 1975 to manage constituent services, while today, emails, the internet, and social media are ubiquitous Senate-wide. Collectively, these oral histories help to promote a fuller and richer understanding of the institution’s evolution and of its role in governing the nation.

The advent of the internet in the mid-1990s provided new opportunities to share Senate history with a broader range of audiences. When Betty Koed joined the team as assistant historian in 1998, she began populating the (then relatively) new Senate website with oral history transcripts and historical information. Today, the Historical Office has integrated a wealth of Senate history across Senate.gov, created a Senate Stories blog, and developed online exhibits including “The Civil War: The Senate’s Story,” “The Civil Rights Act of 1964,” “States in the Senate,” and “Women of the Senate.”

Since its founding, the Historical Office has developed and maintained a reputation among senators, staff, journalists, scholars, and the general public for providing fact-based, non-partisan information about the institution’s history. Its staff manage dozens of statistical lists and maintain information about senators and vice presidents in the online Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Historians lead custom tours for members and staff and deliver history “minutes”—brief Senate stories about a subject of their choosing—at the party conference luncheons and for the Senate spouses. They offer brown bag lunch talks, deliver committee and state legacy briefings, and host an annual Constitution Day event. Historical Office staff have provided background and research support for dozens of books on the Senate, as well as historic events such as inaugural ceremonies, three presidential impeachment trials, and the 1987 congressional session convened in Philadelphia to commemorate the bicentennial of the Great Compromise which paved the way for the signing of the U.S. Constitution.

In addition to these varied services, Senate historians have supported a number of projects for members and committees, including Senator Robert C. Byrd’s four-volume The Senate, 1789–1989; Senator Robert Dole’s Historical Almanac of the United States Senate; the executive sessions of the Committees on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (1953) and Foreign Relations (1947–1968); and Senator Mark Hatfield’s Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993. The Historical Office team has authored print publications including the United States Senate Election, Expulsion and Censure Cases, 1793–1990 (1995); 200 Notable Days: Senate Stories 1787–2002 (2006); Scenes: People, Places, and Events That Shaped the United States Senate (2022); and Pro Tem: Presidents Pro Tempore of the United States Senate (2024). The Office has helped to document party histories by editing the minutes of the Republican and Democratic Conferences and producing A History of the United States Senate Republican Policy Committee, 1947–1997. These publications have been illustrated, in part, with images drawn from the Historical Office’s rich photo collection.

During the past half-century, the Historical Office has adapted to meet the needs of an ever-evolving institution while continuing to provide the services first articulated by Secretary of the Senate Valeo in 1975. Today, its staff of 12 historians and archivists are dedicated to preserving and promoting Senate history for the next 50 years.

Notes

1. Letter from Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., to the Honorable Mike Mansfield, May 6, 1974, in Senate Historical Office files.

2. Senate Committee on Appropriations, Legislative Branch Appropriations for Fiscal Year 1976: Hearings on H.R. 6950, 94th Cong., 1st sess., April 21, 1975,1258.

3. Mack Thompson to Mr. Richard Baker, March 25, 1976, in Senate Historical Office files; “Senate Historian,” Roll Call, October 23, 1975; “Senate Office To Publish Declassified Documents,” New York Times, October 19, 1975.

4. "Richard A. Baker: Senate Historian, 1975–2009," Oral History Interviews, May 27, 2010, to September 22, 2010, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.; Richard A. Baker, “Managing Congressional Papers: A View of the Senate,” American Archivist 41, no. 3 (July 1978): 291–96.

|

| 202507 23Revisiting Seth Eastman’s Military Fort Paintings After 150 Years

July 23, 2025

This summer marks 150 years since the completion of Seth Eastman’s series of 17 paintings depicting U.S. military forts and West Point, which have been in the possession of Congress since their acquisition in 1875. Eight of these paintings are in the U.S. Senate Collection, and the other nine are in the collection of the U.S. House of Representatives. This anniversary provides a timely opportunity to revisit how Eastman’s military and artistic background informed his receipt of the commission and his approach to depicting these subjects.

The artist Seth Eastman was reportedly putting the finishing touches on his painting West Point, New York, when he died suddenly of a stroke in his Washington, DC, studio on August 31, 1875. This canvas was the last of a series of 17 paintings depicting mainly U.S. military forts that the artist created for Congress between 1870 and 1875. The paintings have been a fixture in the Capitol for most of their history. After their acquisition in 1875, they initially hung in spaces occupied by the House Committee on Military Affairs and later in the Cannon House Office Building. By early 1940, they had returned to the Capitol for public display in the first-floor west corridor. Eight of the paintings hang on the Senate side of the corridor and nine on the House side. Since the establishment of the Senate Commission on Art in 1968, the eight fort paintings in the Senate wing have been cared for as part of the U.S. Senate Collection. The 150th anniversary of the completion of these paintings provides a timely opportunity to revisit how Eastman’s military and artistic background informed his receipt of the commission and his approach to depicting these subjects.1

“Paintings from His Own Designs”

The genesis of the series was a joint resolution introduced by Representative Robert C. Schenck of Ohio on March 26, 1867 (H.J. Res. 42). Schenck, the chairmen of the Committee on Ways and Means, proposed “authorizing the employment of Brevet Brigadier General Seth Eastman of the United States Army, now on the retired list, to duty…to execut[e] under the supervision of the Architect of the Capitol…paintings from his own designs for the decorations of the rooms of the Committee on Indian Affairs and on Military Affairs of the Senate and House of Representatives, and other parts of the Capitol.” Though the House approved the resolution, Senator Henry Wilson, chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs and the Militia, “moved its indefinite postponement,” which was agreed to on March 2, 1868. With the joint resolution tabled in the Senate, the Architect of the Capitol Edward Clark moved forward separately to have the artist make paintings first for the House Committee on Indian Affairs (a series of nine paintings completed in 1869) and then for the Committee on Military Affairs (1870–1875).2

As both a military officer and an artist, Eastman was well positioned to create artwork for the federal government. Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, he was the eldest of 13 children. Though his father hoped he would attend Bowdoin College, young Eastman had an interest in the military and enrolled at West Point in July 1824 at the age of 16 years old. Though Eastman was not generally a strong student—he took five years to graduate instead of the usual four—he excelled in draftsmanship. In the two-year art class at the military academy, he learned skills relevant to military work, including figure drawing, landscape drawing, and topographical drawing.3

Eastman’s approach to depicting forts, with its focus on architectural details and the structures’ relationship to the landscape, evidences this training. An October 1829 pencil sketch that Eastman made at Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien, Michigan Territory (present-day Wisconsin), shows many of the hallmarks of his series of fort paintings executed more than four decades later. Eastman’s first assignment after graduating from West Point was to help rebuild Fort Crawford, where then-Colonel Zachary Taylor was overseeing the construction of a new stone fort to replace the original timber one. Eastman’s drawing illustrates the first Fort Crawford from a slightly elevated viewpoint, with the fort located in the middle ground and boats on the Mississippi River visible in the foreground. The overall mood of the work is calm and serene with placid water and cloudless skies. Though Eastman did not illustrate Fort Crawford in his 1870s fort paintings, the artistic strategies employed in this early drawing of a fort anticipate, in overall effect, many of the later paintings. Fort Knox, Maine, for example, similarly illustrates the fort from a nearly identical perspective, with the composition divided horizontally into sky, land, and water. Small civilian figures in boats in the foreground of both works contribute to the overall quotidian impressions of the scenes.

“Gallant American Officer [with] Taste and Artistic Ability”

Members of Congress who advocated for Eastman to receive the commission viewed him as a skilled artist who could provide quality artwork for the Capitol at an affordable price. Because the federal government already employed him as a member of the military, Eastman could be hired to create the artwork as part of his military duties and, therefore, at little additional cost. Representative Schenck, in his proposed joint resolution, emphasized this point, clarifying that “no additional compensation for such service is to be paid to said Eastman beyond his pay, allowances and emoluments” as a brevet brigadier general in the United States Army. Members of the Senate had previously championed Eastman as a potential cost-effective source of imagery for the Capitol. During a discussion on the Senate floor on June 10, 1852, about whether Congress should purchase a collection of paintings of Native American subjects by artist George Catlin, Senator Solon Borland of Arkansas spoke in favor of commissioning Eastman to create artwork instead. The artist was, at the time, illustrating Native American subjects for Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s six-part publication, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (published 1851–1857), authorized by an act of Congress and produced by the Office of Indian Affairs. Because of this, Borland argued that the quality of Eastman’s artwork was already evident. In addition, he noted, Eastman was willing to do the work for his regular military pay, a sum far less than Catlin’s fee.4

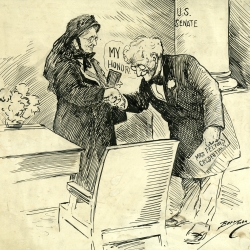

Besides the attractive price offered by Eastman, the artist was also an appealing choice for many members of Congress because of his nationality as a native-born U.S. citizen. The recent and extensive efforts to decorate the new Capitol extensions during the 1850s and 1860s had prompted heated debates within Congress about the extent to which Engineer of the Capitol Montgomery C. Meigs had awarded contracts to foreign-born artists, especially Constantino Brumidi. Brumidi created the elaborate fresco decorations found throughout much of the Senate wing and the Capitol Rotunda between 1855 and 1880. Today these murals are considered among the most iconic and beloved features of the Capitol’s interior, but they were once a source of outrage for many American-born artists who wished that they, too, could benefit from government patronage as well as for members of Congress who believed federal funds should support American artists instead. (Brumidi became a naturalized citizen in 1857, but that did little to quell the criticism.) The Washington Art Association, an organization of which Eastman was an active member, worked during this period to win broader congressional support to reform the process of awarding government arts commissions. Eastman served as a director of the Washington Art Association in 1858 and 1860 and exhibited paintings at the organization’s annual exhibition between these years. Sculptor Horatio Stone, who served as the president of the Washington Art Association, argued specifically that artists—not engineers (a direct attack on Meigs)—should determine who gets the commissions and approves the designs. Furthermore, Stone emphasized the nationalism behind the group’s efforts, declaring, “The time has come for a more expanded exertion of the genius of this nation upon works of national art.”5

In this context, Eastman’s status as a native-born U.S. citizen and his military service made him a politically appealing choice. Representative Schenck pointed to these facts in 1867, when he proposed that Congress hire Eastman, stating, “We have been paying for decorations, some displaying good taste and others of a tawdry character, a great deal of money to Italian artists and others, while we have American talent much more competent for the work.” Singling out Eastman specifically as possessing “native talent,” Schenck added, “I think under the circumstances a gallant American officer, who has taste and artistic ability, should be permitted to be assigned to this duty.” Ultimately, Schenck prevailed, and, by 1870, Eastman was at work on the series for the Committee of Military Affairs.6

Forts from All Regions

It is not certain why Eastman portrayed the 15 particular locations depicted in the series, and whether the sites were suggested by the artist, the committee, or a combination of both. The paintings picture locations in various states, including Maine (Fort Knox and Forts Scammel and Gorges), Connecticut (Fort Trumbull), New York (West Point, Fort Lafayette, and Forts Tompkins and Wadsworth), Pennsylvania (Fort Mifflin), Delaware (Fort Delaware), South Carolina (three different paintings of Fort Sumter), Florida (Fort Taylor and Fort Jefferson), Michigan (Fort Mackinac), Minnesota (Fort Snelling), North Dakota Territory (Fort Rice), and New Mexico Territory (Fort Defiance). It was unlikely that Eastman, who was advanced in years and in poor health at the time of the commission, visited the forts during the five-year period he painted them. However, he had been stationed at or visited at least three of them earlier in his military career. Perhaps his familiarity with West Point (where he lived in 1824–1829 and 1833–1840), Fort Snelling (where he was stationed in 1830–1831 and 1841–1848), and Fort Mifflin (where he was in command in 1864–1865) helped determine their inclusion in the series. When creating his later oil-on-canvas series, the artist drew from an extensive archive of drawings and watercolors that he had made of these locations years earlier. His role as a Mustering and Dispersing Officer for his home state of Maine and for New Hampshire at the beginning of the Civil War (1861–1863) may have also brought him into contact with Fort Knox (which garrisoned troops during the war) and Forts Gorges and Scammel. Eastman likely had access to plans, elevations, and even photographs of the forts in the series that he probably did not visit in person. Trained in topographical draftsmanship, he would have had the skills necessary to translate these resources into his own compositions.7

Eastman had also portrayed some locations, like Fort Defiance, in prior publications. Eastman’s painting Fort Defiance, New Mexico (now Arizona) is very similar to the illustration he made for Schoolcraft’s publication. Established as a U.S. military fort in 1851, the site was largely abandoned in 1861 but was reestablished in 1868 as an Indian agency rather than an active fort. Eastman’s illustration published in Schoolcraft’s text indicates that it was based on a sketch provided by Lt. Col. Joseph H. Eaton, who was stationed at the fort for “frontier duty” in 1852–1853. Eaton attended West Point from 1831 to 1835, and it is probable that he would have studied with Eastman, who joined the faculty there as a drawing instructor in 1833. Eastman must have used Eaton’s sketch as the basis for the various preparatory studies he created while working to illustrate Schoolcraft’s publication, including a drawing and watercolor that are both in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.8

Architectural Tranquility

Though several of the locations played a role in the recent Civil War, Eastman’s paintings show little evidence of this history. Instead, the artist took a deliberately restrained pictorial approach to depicting the forts. His tranquil representation of Fort Delaware, for example, reveals nothing of the site’s history as an infamous prisoner of war camp for captured Confederate soldiers. Completed in 1859, Fort Delaware was the United States’ largest fort on the eve of the Civil War. In 1862 it became a prison, and by the following year most of the Confederate soldiers captured at the Battle of Gettysburg were held in barracks located just northwest of the fort. By the end of the war, more than 30,000 people had been imprisoned there. Due to overcrowding, conditions were notoriously bad, and diseases spread rampantly; more than two thousand prisoners died in custody. Though Eastman was never stationed at Fort Delaware, he had direct knowledge of such Civil War prisons. In 1864 he was ordered to prepare and command what would become known as one of the most brutal Civil War prisons, Elmira in New York, which, like Fort Delaware, was plagued by poor sanitation and insufficient supplies. Eastman’s painting of Fort Delaware shows the low block of the massive fort as seen from the east, nestled into a serene landscape and softly illuminated by the morning light.9

This restrained pictorial approach was a conscious decision. On June 16, 1870, Representative John A. Logan of Illinois, chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs, wrote a letter to Architect of the Capitol Edward Clark requesting that Eastman make paintings “for the decoration of the Military Committee Room of the House of Representatives, in the same manner as the room for the Committee on Indian Affairs.” Logan and Eastman met to discuss the commission, and the two agreed that the canvases should depict the architecture of the forts and a view of West Point, rather than representing active battle scenes.10

This choice is a marked contrast from another mid-19th century commission for the Capitol that depicts a fortress, The Battle of Chapultepec (Storming of Chapultepec), which was painted in 1857–1858 by artist James Walker and delivered to the Capitol in 1862. The painting, commissioned as part of Meigs’s program to decorate the rooms of the newly constructed Capitol extensions, pictures the consultation between General John Anthony Quitman and his officers during the storming of the Mexican fortress at Chapultepec on September 13, 1847. Chapultepec Castle appears high on a hill under a dramatic sky, with dynamic crowds of American soldiers readying for battle in the foreground. After reviewing Walker’s studies for the painting, Meigs described them in his journal as “as full of life and knowledge as any battle pieces I have ever seen.” Meigs’s initial notes about the painting reveal he intended for it to hang in the meeting room of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. However, soon thereafter, records indicate that the painting was promised for the House Committee on Military Affairs. Its completion was much delayed due to uncertainties around funding (driven, in part, by the debates, discussed above, about how federal art commissions should be awarded); after its arrival at the Capitol in 1862, it was installed in the west grand staircase of the Senate wing where it hung for more than a century. Three years later, in 1865, the Joint Committee on the Library commissioned artist William Henry Powell to paint another monumental battle scene, Battle of Lake Erie, which was installed in the east grand staircase of the Senate wing upon its completion in 1873. These two monumental battle scenes, with their emphasis on narrative and drama, offered an alternative artistic vision for celebrating American military achievement.11

Today, the Senate wing of the Capitol features a wide variety of fine art in the public staircases and corridors, including Eastman's fort series, Brumidi's murals, and Powell's naval battle scene. The historical nuances of debates about which artists should decorate the Capitol extensions, who should award the commissions, and how the nation’s military might should be represented are no longer obvious. The anniversary of the completion of Eastman’s fort paintings prompts a deeper look into the paintings’ origins and their relationship to other works of art commissioned for the Capitol around the same time.

Notes

1. Patricia Condon Johnston, “Seth Eastman’s West,” American History (August 19, 1996), HistoryNet.com, accessed July 14, 2025, https://www.historynet.com/seth-eastmans-west-october-96-american-history-feature/; William Kloss and Diane K. Skvarla, “Principal Fortifications of the United States,” in United States Senate Catalogue of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2002), 128–29.

2. Congressional Globe, 40th Cong., 1st sess., March 26, 1867, 361–62; Congressional Globe, 40th Cong., 2nd sess., March 2, 1868, 1567; Felicia Wivchar, “The House Indian Affairs Commission—Seth Eastman’s American Indian Paintings in Context,” Federal History 2 (2010): 19; letter from Edward Clark to Seth Eastman, June 16, 1870, Office of Senate Curator files.

3. John Francis McDermott, Seth Eastman: Pictorial History of the Indian (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), 6–7, 11–12.

4. Congressional Globe, 40th Cong., 1st sess., March 26, 1867, 361–62; Congressional Globe, 32nd Cong., 1st sess., June 10, 1852, 1548; Brian W. Dippie, Catlin and His Contemporaries: The Politics of Patronage (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 154, 173.

5. Josephine Cobb, “The Washington Art Association: An Exhibition Record, 1856–1860,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., 63/65 (1963/1965): 181, quote on 124.

6. Congressional Globe, 40th Cong., 1st sess., March 26, 1867, 361–62.

7. Bvt. Maj.-Gen. George W. Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., from Its Establishment, in 1802, to 1890, with the Early History of the United States Military Academy, 3rd ed., vol. 1 (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company; Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1891), 435–436; Kloss and Skvarla, “Principal Fortifications of the United States,” 129.

8. Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1854), Part 4, 210, Plate 30; Kloss and Skvarla, “Principal Fortifications of the United States,” 130; Cullum, Biographical Register, 619; "Fort Defiance I," Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accessed July 14, 2025, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/158320/fort-defiance-i; "Fort Defiance II," Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accessed July 14, 2025, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/4502/fort-defiance-ii?ctx=2df7c5ae-93b3-4784-b296-42686a02e570&idx=0.

9. Kloss and Skvarla, “Principal Fortifications of the United States,” 132; “Confederate Burials in the National Cemetery,” U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/signs/Finns-Point-National-Cemetery-NJ-Confederate-Burials-Interpretive-Sign.pdf.

10. Herbert Hart, “The Forts of Seth Eastman,” Periodical 7, no. 1 (Spring 1976): 22.

11. Wendy Wolff, ed., Capitol Builder: The Shorthand Journal of Montgomery C. Meigs, 1853–1859, 1861 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2001), 534; letter from Meigs to Walker, October 9, 1857, Office of Senate Curator files.

|

| 202506 20From Paper to Pixels: The Transformation of Congressional Archives

June 20, 2025

The legacy of generations of U.S. senators—contained in letters, memos, photographs, handwritten notes—rests in climate-controlled stacks, preserved by acid-free folders for the enduring curiosity of researchers. But in recent decades, the nature of archives has changed. Where once the record lived in ink and envelope, it now resides in networks, clouds, and code. From the meticulously penned letters of Senator Albert Beveridge to the terabyte of digital data in Senator John McCain’s recent donation, the evolution of archival practice reveals both challenge and opportunity.

The legacy of generations of U.S. senators—contained in letters, memos, photographs, handwritten notes—rests in climate-controlled stacks, preserved by acid-free folders for the enduring curiosity of researchers. But in recent decades, the nature of archives has changed. Where once the record lived in ink and envelope, it now resides in networks, clouds, and code.

The transformation of congressional archives from paper to born-digital formats reflects more than a shift in technology. It marks a turning point in how our national memory is preserved and how these unique records are accessed by future generations. From the meticulously penned letters of Senator Albert Beveridge to the terabyte of digital data in Senator John McCain’s recent donation, the evolution of archival practice reveals both challenge and opportunity.

The Tangibility of Tradition: The Albert J. Beveridge Papers

Republican Albert J. Beveridge represented Indiana in the U.S. Senate from 1899 to 1911. Throughout his career he championed several progressive causes, including consumer food safety and a 1906 proposal to ban child labor, which eventually led to the passage of the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act of 1916. The bulk of his papers, housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., span more than 40 years of American thought and politics. These are records you can touch: crisp correspondence written in iron gall ink, typed speeches on onion-skin paper, and newspaper clippings folded with care. Comprising roughly 100,000 items, this collection reflects the conventions of its age—arranged into defined series and stored in more than 400 carefully arranged boxes on climate-controlled shelves.1

The challenges of preserving such a collection are tactile and environmental. Paper degrades. Ink fades. Heat and humidity hasten decay. Archivists face constant vigilance—controlling light exposure, monitoring temperature, and conserving fragile pages. Accessibility, too, presents challenges. With no digital surrogates and limited item-level description, researchers rely upon finding aids and box lists, rather than modern keyword searches and remote computer access.

Yet there is a poetry to these physical documents. The weight of history is felt quite literally in one’s hands. Senator Beveridge’s papers offer an intimate, almost sensory connection to the past—one that remains indispensable, even as archival strategies have evolved. The decision to place his papers in the Library of Congress ensured that accessibility to this connection would outlive the senator’s lifetime. Researchers who utilize Beveridge’s records can find drafts of speeches and articles, general correspondence, as well as records tracing the evolution of state and national politics.2

Bridging Eras: The Daniel Patrick Moynihan Papers

Senators’ commitment to provide public access to their congressional records carried into the digital age. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Democrat, represented New York from 1977 to 2001, a period during which he emerged as one of the Senate’s leading voices on social welfare policy, intelligence oversight, and government transparency. His career, like his papers, spanned textual and digital worlds. Housed in the Library of Congress, his 1.3 million-item collection includes not only the expected letters, memos, and photographs, but also 275 digital files—early artifacts of a changing technological landscape.3

These born-digital components, modest in number but rich in complexity, introduced new demands on archival work. Floppy disks and CD-ROMs offered neither durability nor standardization. Rapidly evolving file formats threatened obsolescence almost as quickly as they emerged. Some emails arrived as printed pages, others as saved text files, and archivists were left to piece together the whole, tracing context, connection, and chronology across media types.

Senator Moynihan’s archive is a study in contrast—a bridge between worlds. As technology evolved, so too did the demands on archival practice. For archivists, this collection offered an early test case in managing hybrid records, foreshadowing the complexity that would soon become the norm. For researchers, it remains a vivid portrait of an era when word processors began to replace typewriters and the archive started to slip beyond the page. That portrait exists today because Senator Moynihan understood the importance of preserving and making available all of his records.

Into the Digital Fold: The Joseph Lieberman Papers

The political career of Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut spanned 40 years, from his service in the state senate (1970–1980) to his terms as state attorney general (1983, 1986–1988), to his tenure as U.S. senator (1989–2013). By the time he retired in 2013, email was ubiquitous, documents lived on shared drives, and offices were moving quickly toward a paperless environment. His donation of his political collection to the Library of Congress included 1,500 boxes of physical material and an extensive volume of digital content—emails, early word processing files, staff memos, legislative drafts, digital photographs, and other electronic records—from his personal Senate office. These records document Lieberman’s legislative efforts to protect the environment, safeguard the nation through the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, secure access to healthcare, and advance civil rights, among other accomplishments.4

During Senator Lieberman’s tenure, his staff did what few had done before—they prepared their digital records for eventual deposit in an archive. Aware of the long-term importance of these records, his staff established policies to save documents, organize file folders, and capture day-to-day interactions and decision-making. By choosing to include these digital records in his collection, particularly internal communications and staff correspondence (then an uncommon practice), Senator Lieberman, a Democrat turned Independent, demonstrated a commitment to government accountability. “I have long been a proponent of open government and transparency,” Lieberman explained. “Because so much of our work is conducted electronically, it seemed logical for me to include my emails as part of my Senate archives.”5

Archivists, in turn, faced a daunting task: processing terabytes of files in a jumble of formats, many tied to proprietary platforms, some stored in legacy systems long since abandoned. Maintaining such a collection demands more than hardware. It requires fluency in digital archival standards and systems capable of safeguarding the integrity of digital records. Context must be preserved—not just the content of an email, but who sent it, who received it, and what thread it answered. Without this, digital records become hollow shells, stripped of meaning.

Digital collections raise complex questions for archivists—how to balance openness with privacy, manage large quantities of sensitive correspondence, and navigate issues of ownership, redaction, and access in a networked environment. As processing of his collection continues in preparation for public access, Senator Lieberman’s papers serve as an early test case for how digital legacies can be responsibly managed in an era of rapid technological change. His collection pushed the boundaries of traditional archival practice.

Archives in the Cloud: The John S. McCain Papers

While the Lieberman Papers reflect a growing awareness of the importance of digital stewardship, the Senator John S. McCain Papers at Arizona State University (ASU) offer a detailed case study of the challenges and solutions that come with managing a born-digital archive that encompasses millions of files.

Republican John S. McCain III represented Arizona in the House of Representatives from 1983 to 1987 and in the U.S. Senate from 1987 until his death in 2018. McCain’s legislative initiatives included campaign finance reform, veterans’ affairs, national security and defense, immigration, and international human rights. ASU first acquired Senator McCain's House papers in the late 1990s. The McCain family significantly expanded the collection by donating the senator's extensive Senate and campaign records to ASU in 2019. This donation included more than 1,900 linear feet of paper and over 1 terabyte of digital files—totaling more than 3.9 million individual items and thousands of unique file types.6

Managing a modern congressional collection of significant size and complexity requires thoughtful investment in space, technology, and personnel. Successful stewardship depends on assembling a team with expertise in both traditional archival practices and digital preservation strategies. Institutions must often acquire specialized equipment, secure storage solutions, and robust computing infrastructure to support access, processing, and long-term care. Archivists may apply methods such as selective sampling and digital forensics to assess, stabilize, and prepare the collection for future use while maintaining the authenticity and integrity of the records.

The McCain Papers and the plan for their eventual availability to researchers and the public demonstrate how modern congressional archives are shaped not just by what is donated but also by how they are managed. Senator McCain’s records reflect more than a senator’s career; they show how a legacy of public service now depends on the effective preservation and accessibility of digital information. Preserving born-digital records at this scale requires institutional readiness, including adequate infrastructure, technical skills, strategic planning, and meaningful engagement with the public through outreach, collaboration, and transparency. For repositories facing similar challenges, the McCain collection provides a model for preserving and providing access to the complex digital record of a senator’s public service.

The Archival Pivot: Challenges and Continuities Toward Legacy and Stewardship

These four collections reflect a clear evolution from the linear logic of paper files to the dynamic sprawl of digital ecosystems. Each stage has demanded its own kind of care. For paper, that care means controlled humidity, acid-free folders, and meticulous arrangement. For hybrid collections, it means recovering obsolete formats, aligning analog and digital content, and building new description practices. For digital archives, it means maintaining file integrity, navigating proprietary systems, preserving metadata context, and ensuring long-term access in the face of software drift and platform dependency. In the early 21st century, a press release might begin as a Word doc, cycle through multiple drafts, be emailed to staff, published on a website, and posted on social media, all in a matter of hours. Capturing that full chain of activity is essential to understanding the record in its original context.

Archival practices have adapted to this shifting technological landscape, developing new practices to ensure that the past can be examined with rigor and interpreted with context. This evolution is not merely technical—it is political, historical, and deeply human. When a senator chooses to preserve their legacy in a repository committed to long-term access, it is an act of foresight and public service. It offers future generations insight into the values, debates, and decisions that shaped a given era. But this insight is only possible if the records survive, and survival now depends on action.

A Final Reflection

As historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. observed in a 1974 letter to Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield and Minority Leader Hugh Scott, “If we are going to persuade the nation that Congress plays a vital role in the formation of national policy, Congress will have to cooperate by providing evidence for its contributions.” Congressional archives safeguard historical memory—not just the words themselves, but the provenance that makes them trustworthy. Anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues in Silencing the Past that archives are shaped during the “moment of fact assembly,” when decisions about what to preserve, how to describe it, and what to exclude can influence the contours of collective memory. While individual memories may fade, congressional archival collections anchor our shared understanding of the past by documenting governmental processes. Whether held in acid-free folders or stored on secure servers, these records include the raw material of history, ready to be shaped and assembled by future generations.7

Notes

1. Albert J. Beveridge papers, 1789–1943, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, online finding aid accessed June 10, 2025, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011132.

2. Ibid.

3. Daniel P. Moynihan papers, 1765–2003, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, online finding aid accessed June 10, 2025, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms008066.

4. Ana Radelat, “Burnishing his legacy, Lieberman to leave his official papers to the Library of Congress,” CT Mirror, August 28, 2013, accessed May 20, 2025, https://perma.cc/A7NE-PKTL.

5. “Lieberman Archives Committee Emails,” Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, January 7, 2013, accessed June 5, 2025, https://perma.cc/B7MM-ML4N.

6. “From the archives: A glimpse into the future library and museum,” Arizona State University McCain Library and Museum, accessed June 5, 2025, https://perma.cc/S34N-CYR8.

7. Letter from Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., to Mike Mansfield, May 6, 1974, Administrative Files, Senate Historical Office; Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 26.

|

| 202503 25The Senate Spares the Belmont House

March 25, 2025