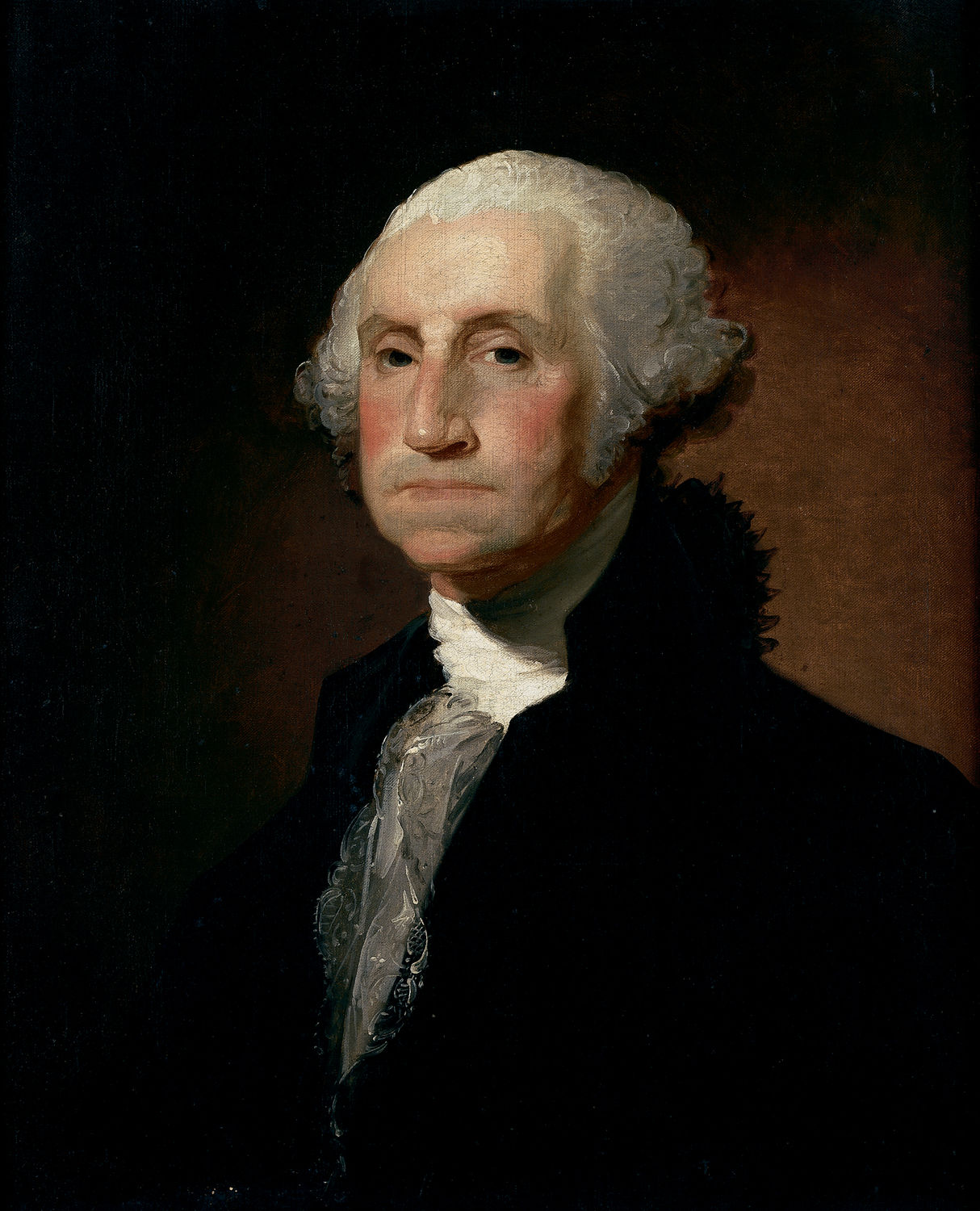

| Title | George Washington |

| Artist/Maker | Gilbert Stuart ( 1755 - 1828 ) |

| Date | 1796 ca.–1805 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | Sight: h. 28.75 x w. 23.625 in. (h. 73.025 x w. 60.0075 cm)

Framed: h. 43.25 x w. 38 in. (h. 109.855 x w. 96.52 cm) |

| Credit Line | U.S. Senate Collection |

| Accession Number | 31.00004.000 |

This skillful replica by Gilbert Stuart of his Athenaeum portrait of George Washington is commonly known as the “Pennington portrait.” It takes its name from its first owner, Edward Pennington, a Philadelphian who was a founder of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. It may be assumed that Pennington acquired the Washington portrait around the time Stuart was in Bordentown, New Jersey, where Stuart left his family while he was in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, and where at least some of Pennington’s family lived. (Stuart painted a portrait of Edward Pennington around 1802, and the painting is now located at the Atwater Kent Museum in Philadelphia.) The Washington portrait owned by Pennington later came into the possession of Mrs. Cicero W. Harris of Washington, D.C., who in 1886 sold it to the Joint Committee on the Library for placement in the U.S. Capitol.

In this replica, Stuart paints Washington’s face and hair more boldly and summarily than he does in some other replicas. For example, he emulates the fleshy bridge of Washington’s nose with a creamy swirl of paint. The flesh coloring is nicely balanced, without the strong crimson cheeks Stuart often favors, although his characteristic use of red in the shadows of the upper eyelids is apparent. The modeling of the mouth seems somewhat hesitant, as if the artist were trying to modify the puffy distortion caused by the president’s notorious false teeth. The paint is applied with particular fluency in the lacy shirtfront.

There is a compelling directness about this image that is explained, in part, by the secure placement of the head on the canvas. When compared with the Senate’s other Athenaeum-type head—the Chesnut portrait—the Pennington head is more securely positioned on the canvas. It is firmly in the upper half of the field and more strongly centered. Washington’s left eye lies precisely at the horizontal midpoint. Were the head to rotate to a frontal position, it would be more symmetrically placed than would the head in the Chesnut portrait. The white neckcloth—the strongest, brightest tone in the painting—provides a solid pedestal for the head.

Equally admirable in this version is Stuart’s control of the lighting and, therefore, the coherence of forms in space. For instance, a nicely gauged, faint highlight defines the back of the high coat collar where it meets the striking bow of black ribbon. The ribbon secures the black silk bag that holds the long hair at the back. (This fashion appeared around 1770; alternatively, the back hair was dressed in a queue, or pigtail.) The hair ribbon is unusually elaborate, larger than that used on a pigtail (which would not be visible from the front), and its serrated contour is visually confusing to the modern viewer. But Stuart’s subtle highlighting helps differentiate the shapes within that large black area. In addition, the gradation of light across the background suggests space and gives the head still more force while enhancing the effective, persuasive design of the torso, whose proper right contour has a melodic descent.

The painting has hung in various locations in the Capitol since it was acquired, and it was also displayed at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1932 as part of an exhibition celebrating the bicentennial of Washington’s birth.

George Washington, first president of the United States, earned the epithet Father of His Country for his great leadership, both in the fight for independence and in unifying the new nation under a central government. Washington was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, and worked as a surveyor in his youth. In 1752 he inherited a family estate, Mount Vernon, upon the death of a half brother, Lawrence. Washington's military career began in 1753, when he accepted an appointment to carry a warning to French forces who had pushed into British territory in the Ohio valley. In subsequent military assignments, Washington distinguished himself against the French, first while aiding General Edward Braddock and later as commander-in-chief of all Virginia militia.

In 1758 Washington returned to civilian life as a gentleman-farmer at Mount Vernon and soon took a seat in the Virginia house of burgesses. As a planter, Washington had firsthand knowledge of the economic restrictions being imposed by Britain, and as a Virginia legislator, he supported political efforts to curtail British control of the colonies. Washington was selected to serve as a delegate to the first and second Continental Congresses, and in June 1775 he was chosen to command the American forces. He successfully led the Continental army through eight difficult years of war for independence.

In 1783, after the Revolution, Washington resigned his military commission to Congress at Annapolis, Maryland. Recognizing the need for a strong central government, he served as president of the federal convention charged with drafting the Constitution. Reluctantly, he accepted the will of his colleagues to become president of the new nation, and he was inaugurated in New York City on April 30, 1789. Contending with the ideological struggles within the government, and with hostilities between France and Great Britain, Washington greatly feared the growth of political parties and the dangers of foreign involvement. These issues impelled him to serve a second term as president.

His attempts to solve foreign relations issues during his second term resulted in Jay's Treaty (1794), a vain attempt to regulate trade and settle boundary disputes with Great Britain, and the Pinckney Treaty (1795), which successfully settled such issues with Spain. Washington also acted vigorously to enforce federal authority by quashing the Whiskey Rebellion, during which liquor producers in western Pennsylvania threatened the new republic by rebelling against an unpopular excise tax on whiskey.

Washington's 1796 Farewell Address to the nation emphasized the need for a unified federal government and warned against party faction and foreign influence. Although often subjected to harsh criticism by his contemporaries, Washington succeeded in giving the new government dignity. He saw a federal financial system firmly established through the efforts of Alexander Hamilton, and he set valuable precedents in the conduct of the executive office. Washington retired to Mount Vernon, where he died on December 14, 1799.