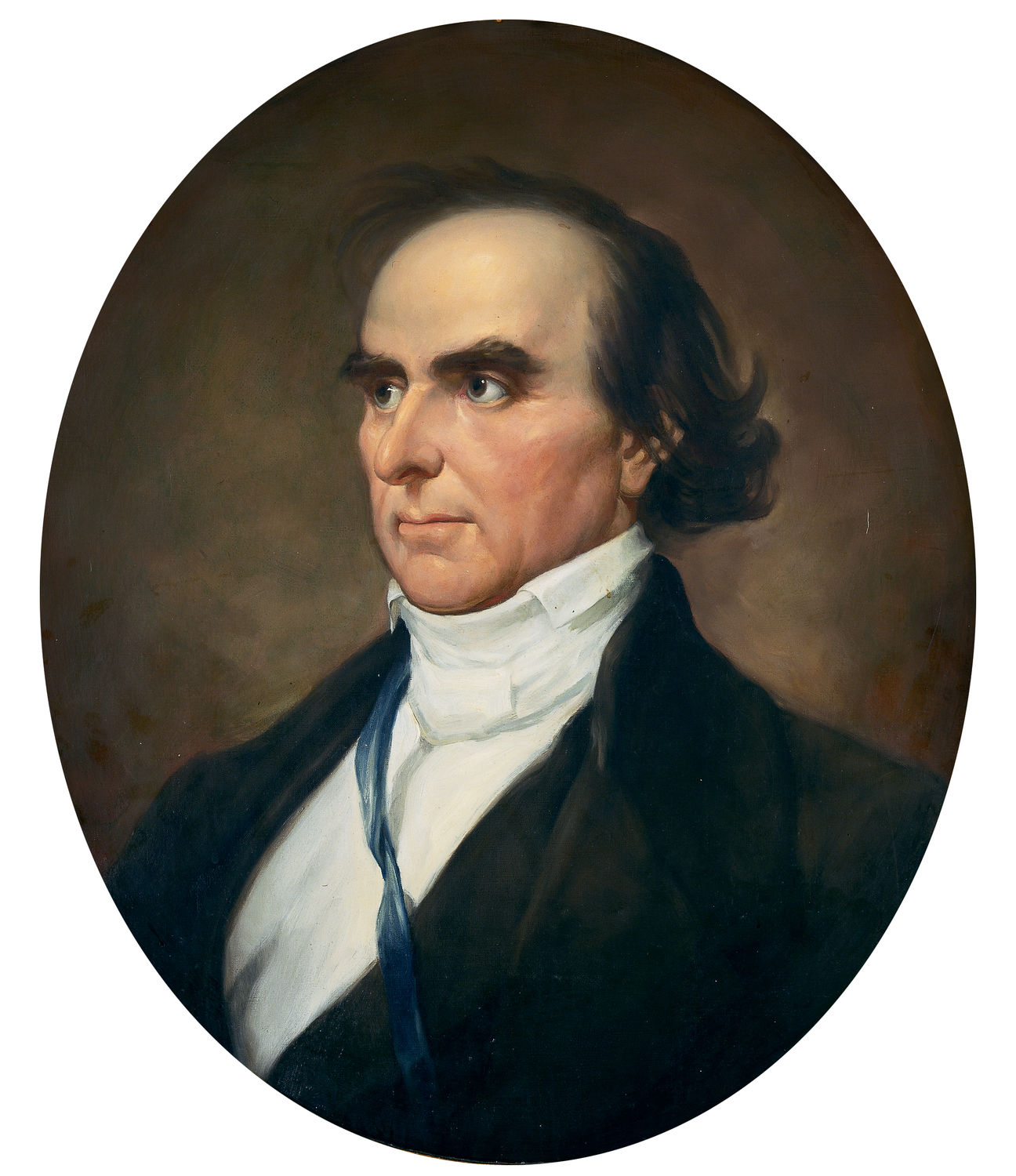

| Title | Daniel Webster |

| Artist/Maker | Adrian S. Lamb |

| Date | 1958 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | Sight: h. 22.625 x w. 19.5 in. (h. 57.4675 x w. 49.53 cm)

Canvas: h. 22.75 x w. 19.75 in. (h. 57.785 x w. 50.165 cm) |

| Credit Line | U.S. Senate Collection |

| Accession Number | 32.00006.000 |

To complete the decorative plaster panels in the Senate Reception Room of the U.S. Capitol that had been left vacant since the late 19th century, the Special Committee on the Senate Reception Room was established in 1955. The Senate charged the committee with selecting “five outstanding persons from among all persons, but not a living person, who have served as Members of the Senate since the formation of the Government of the United States.” Paintings of these individuals would then “be placed in the five unfilled spaces in the Senate reception room.” [1]

The committee consisted of four senior senators and one freshman senator. Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson appointed the freshman, John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, to be the committee’s chairman. Kennedy was an ideal choice; his popular book, Profiles in Courage, skillfully examined the careers of eight outstanding former senators. The Kennedy committee spent two years surveying the nation’s leading historians and political scientists, and easily identified three 19th-century senators: Henry Clay of Kentucky, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts. After much debate, the committee also selected two 20th-century members: Robert M. La Follette, Sr., of Wisconsin and Robert A. Taft, Sr., of Ohio. A special Senate commission, composed of experts in the art field, then selected artists for the five paintings, including Adrian Lamb of New York for the portrait of Daniel Webster. The commission determined that Lamb, like the other artists, should “copy some suitable existing portrait or other likeness of his particular subject.” [2] Lamb based his painting on an existing oil by George P.A. Healy in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond. The original portrait, made during a sitting from life in 1848 at Webster’s country home in Marshfield, Massachusetts, had served as a preliminary study for Healy’s monumental historical painting Webster’s Reply to Hayne in Faneuil Hall in Boston. The Virginia museum’s Webster likeness was one of four life studies of the senator executed by Healy during a six-year period.

Adrian Lamb studied at the Art Students League in New York City and at the Academie Julian in Paris before embarking on a career as a portraitist. Lamb’s works are found in many collections, including the White House, the Smithsonian Institution, the U.S. Naval Academy, Harvard University, and the Supreme Court of the United States. For much of his life, Lamb resided in Connecticut and maintained a studio in Manhattan.

1. U.S. Senate, S. Res. 145, 84th Cong., 1st sess., 2 August 1955.

2. U.S. Senate, Proceedings at the Unveiling of the Portraits of Five Outstanding Senators, 86th Cong., 1st sess., 1959, S. Doc. 86-17: 36.

One of the nation's greatest orators, Daniel Webster was both a U.S. senator from Massachusetts and a U.S. representative from Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Webster was born in Salisbury, New Hampshire, and gained national prominence as an attorney while serving five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. He successfully argued several notable cases before the Supreme Court of the United States that helped define the constitutional power of the federal government. In Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, the Court declared in favor of Webster's alma mater, finding private corporation charters to be contracts and therefore protected from interference by state legislative action. In McCulloch v. Maryland, the Court upheld the implied power of Congress to charter a federal bank and rejected the right of states to tax federal agencies. Webster also argued the controversial Gibbons v. Ogden case, in which the Court decided that federal commerce regulations take precedence over the interstate commerce laws of individual states.

After his election to the U.S. Senate in 1827, Webster established his oratorical reputation in the famous 1830 debate with Robert Young Hayne of South Carolina over the issue of states' rights and nullification. Defending the concept of a strong national government, Webster delivered on January 26 and 27 his famous reply to Hayne. “We do not impose geographical limits to our patriotic feeling,” he insisted, arguing that every state had an interest in the development of the nation and that senators must rise above local and regional narrow-mindedness. The Constitution is the supreme law of the land, he warned, and any doctrine that allowed states to override the Constitution would surely lead to civil war and a land drenched with “fraternal blood.” The motto should not be “Liberty first, and Union afterwards,” Webster concluded, but “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!” Within weeks of the debate, Webster had become a national hero. His Senate oration was in greater demand than any other congressional speech in American history. Webster then served a distinguished term as secretary of state from 1841 to 1843, negotiating the Webster-Ashburton Treaty that settled a dispute over the boundary between the U.S. and Canada. He later returned to the Senate, where he championed American industry and opposed free trade.

If Webster's impassioned oratory was legendary, it was intensified by his unforgettable physical presence. Dark in complexion, with penetrating eyes—often likened to glowing coals—he had an electrifying effect on anyone who saw him. Nineteenth-century journalist Oliver Dyer wrote: “The God-like Daniel . . . had broad shoulders, a deep chest, and a large frame. . . . The head, the face, the whole presence of Webster, was kingly, majestic, godlike.” [1]

Increasingly concerned with the sectional controversy threatening the Union, Webster supported Henry Clay's Compromise of 1850. On March 7, 1850, he delivered one of his most important and controversial Senate addresses. Crowds flocked to the Senate Chamber to hear Webster plead the Union's cause, asking for conciliation and understanding: “I wish to speak today not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American. . . . I speak today for the preservation of the Union. Hear me for my cause.” Webster's endorsement of the compromise—including its fugitive slave provisions—helped win its eventual enactment, but doomed the senator's cherished presidential aspirations. Webster became secretary of state again in 1850, and he died two years later at his home in Marshfield, Massachusetts.

1. Oliver Dyer, Great Senators of the United States Forty Years Ago (1848 and 1849) (1889; reprint, Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries, 1972), 251–253.