The War Begins

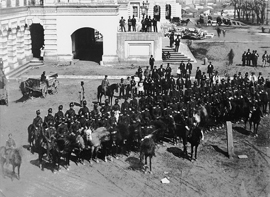

Soon after Lincoln took office, the commander of Fort Sumter in South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor reported that supplies were running low. Several members of the president’s cabinet recommended evacuating the fort. Instead, the president chose to resupply it, but with food rather than with weapons. At 4:40 a.m. on April 12, 1861, Confederate cannons opened fire on Fort Sumter and Union forces surrendered 34 hours later. The attack prompted President Lincoln to issue a proclamation on April 15 calling upon Congress to convene an emergency session on July 4. He also called for 75,000 troops to protect the seat of government and suppress the rebellion—although they were asked to serve for only 90 days.

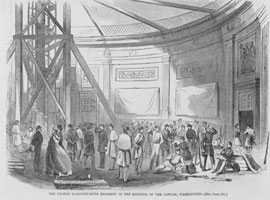

The response across the North to the president’s call was swift. As one journalist recorded, Lincoln’s proclamation “was received with the beating of drums and the ringing notes of the bugle, calling the defenders of the capitol to their colors. Every city and hamlet had its flag-raising.” Senator John Sherman of Ohio later described this impressive reaction in his memoirs: “The response of the loyal states to the call of Lincoln was perhaps the most remarkable uprising of a great people in the history of mankind. Within a few days the road to Washington was opened, but the men who answered the call were not soldiers, but citizens, badly armed, and without drill or discipline.” The first Union troops, volunteers from Pennsylvania, arrived in Washington on April 18 and were quartered in the House wing of the Capitol. The next to arrive was the Sixth Regiment from Massachusetts. Having encountered angry mobs of Southern sympathizers in Baltimore, the Massachusetts soldiers arrived in Washington on April 19 bloodied and exhausted. They established their camp in the Senate Chamber. Longtime Senate doorkeeper Isaac Bassett described the arrival of these embattled troops:

The Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts, nine hundred strong, under the command of Col. Jones, were attacked in Baltimore on their way to Washington. . . . On arriving here these were marched into the Capitol and immediately occupied the Senate Chamber. . . . The col. made the Vice President’s Room his headquarters. They looked tired I saw blood running down their faces. Their clothes were full of dust. Everything was done that could be for their comfort.

Soon Washington was teeming with soldiers, thousands making their camp in and around the Capitol. In a letter to his son on April 19, Architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter commented that “the Capitol itself is turned into a barracks; there will be 30,000 troops here by tomorrow night.” Company E of the National Guard, a group formed from mechanics who had been working in and around the Capitol, made their quarters in the Revolutionary Claims Committee room. A young writer named Theodore Winthrop of the Seventh New York Regiment documented his experience in the Atlantic Monthly, published in July 1861. “Our life in the Capitol was most dramatic and sensational . . . ” he wrote. “We joked, we shouted, we sang, we mounted the Speaker’s desk and made speeches.” Seated at the senators’ desks in the still-new chamber, soldiers used Senate stationery and franked envelopes to correspond with their loved ones back home. In the Capitol Rotunda, a reporter witnessed a young member of the New York Zouaves, “a mere boy,” swing nearly 100 feet on a rope from an interior cornice of the new dome. “It did not seem to be a novel feat to the others, as they noticed it no more than any ordinary occurrence,” the reporter remarked. One of the soldiers’ mock sessions of the Senate was witnessed by a Washington correspondent for the Providence Journal, who wrote:

The presiding officer was just putting the question on a resolution directing the sergeant-at-arms to proceed immediately to the White House and to request the President, if, in his opinion not incompatible with the public interest, to send down a gallon of his best brandy. A motion to strike out the word “Brandy” and substitute “Old Rye” was voted down, on constitutional grounds, and because the “Hon. Senator from South Carolina” who offered it had both his legs on the desk, while the rules only permitted one. And finally a motion was made to clear the galleries as disorderly persons were looking on, evidently to ridicule the proceedings and otherwise behaving in a manner not consistent with the dignity of the Senate.

Despite the levity of these reports, emotions ran high throughout the city. In the Senate Chamber, incensed troops took their bayonets to the desk of former senator Jefferson Davis, seeking to destroy an object once occupied by the new leader of the Confederacy. Hearing the commotion, Bassett rushed to stop the destruction of the desk, reminding the soldiers that it belonged to the United States government, not Davis. “You were put here to protect, and not to destroy!” he shouted. “They stopped immediately and said I was right, they thought it belonged to Jefferson Davis,” Bassett noted in his memoirs.

A militant spirit prevailed when Congress met on July 4, 1861. The more radical members pressed the administration for quick military action. Rumors spread that President Lincoln had no intention of suppressing the rebellion and was simply delaying in order to achieve a compromise with the South. The radicals demanded a quick campaign aimed at the rebel capital of Richmond. Despite the fact that northern troops remained untrained and untested for battle, popular support grew for war. “On to Richmond!” read the headline in the influential New York Tribune: “Forward to Richmond! The Rebel Congress must not be allowed to meet there.” The drumbeat of publicity persuaded Lincoln to launch an early offensive.

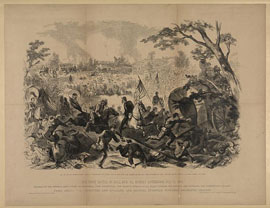

On Sunday, July 21, 1861, some members of Congress gathered in Centreville, Virginia, about 30 miles from Washington, to watch the Union forces march into battle at Bull Run. Civilians rode out in wagons and packed picnic lunches to enjoy while watching the battle (thus known as the “Picnic Battle”). As journalist Benjamin Perley Poore commented, spectators gathered “as they would have gone to see a horse-race or to witness a Fourth of July procession.” The Union army performed well in the morning, but by early afternoon the Confederates brought in reinforcements, staging an intense battle over a space known as Henry Hill. When Union generals finally called retreat around 4:00 p.m., the frightened soldiers fled for their lives, sweeping up civilians in their retreat back to Washington.

Near the battlefield, a group of senators were eating lunch. They heard a loud noise and looked around to see the road filled with retreating soldiers, horses, and wagons. “Turn back, turn back, we’re whipped,” Union soldiers cried as they ran past the spectators. Startled, Michigan senator Zachariah Chandler tried to block the road to stop the retreat. Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio, sensing a humiliating defeat, picked up a discarded rifle and threatened to shoot any soldier who ran. While Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts distributed sandwiches, a Confederate shell destroyed his buggy, forcing him to escape on a stray mule. Iowa senator James Grimes barely avoided capture and vowed never to go near another battlefield. Dismayed, senators returned to Washington to deliver eyewitness accounts to a stunned President Lincoln. Only one member of Congress, New York representative Alfred Ely, made it to Richmond that day—as a prisoner of war.

The Union army’s defeat at Bull Run shocked members of Congress, making it clear that the war would last much longer than 90 days and be harder fought than anyone had expected. The First Battle of Bull Run was only the beginning. It “was the worst event & the best event in our history,” wrote Charles Sumner to Lincoln. It was “the worst, as it was the greatest present calamity & shame,—the best, as it made the extinction of Slavery inevitable.” Congress responded to the defeat on July 29, 1861, by passing legislation that significantly increased the size of the army, and on August 5 by passing an act to better organize the military. These acts provided Lincoln with the largest military power ever conferred upon a president up to that time.

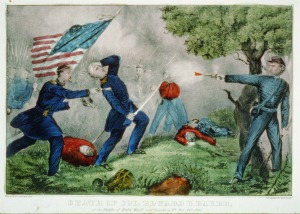

A week after Bull Run, Kentucky senator John C. Breckinridge rose in the Senate Chamber to oppose efforts to declare that a state of insurrection existed. “Here we have been hurling gallant fellows on to death, and the blood of Americans has been shed—for what?” he asked. “Nothing but ruin, utter ruin, to the North, to the South, to the East, to the West, will follow the prosecution of this conflict.” As soon as Breckinridge took his seat, Oregon senator Edward Dickinson Baker, dressed in military uniform, rose to rebut him. An old friend of Lincoln’s from Springfield, Illinois, Baker had resigned from the House of Representatives to lead troops in battle during the Mexican-American War, and had later moved to Oregon, where he was elected senator. In the spring of 1861 he had raised a “California regiment” (actually recruiting on the East Coast), and had spent that morning training his troops. “How could we make peace? Upon what terms?” Baker thundered in reply to Breckinridge. “It is our duty to advance, if we can; to suppress insurrection; to put down rebellion; to scatter the enemy; and when we have done so, to preserve in the terms of the bill, the liberty, lives, and property of the people of the country, by just and fair police regulations.” Encouraged by applause from the gallery, Baker acknowledged that the war would exact a heavy price. “There will be some graves reeking with blood, watered by tears of affection.” Little did Baker know that he was describing his own imminent fate.

When the Senate adjourned the extra session on August 6, 1861, some senators returned to their home states to raise regiments of soldiers. A few, like Baker, donned uniforms themselves. Although Baker turned down a commission as brigadier general so that he could remain a senator, he felt that he could engage in combat while Congress was adjourned. On October 21, 1861, Baker led a brigade of Union volunteers across the Potomac River, seeking to advance on Leesburg, Virginia. Confederate forces stopped them at Ball’s Bluff, trapping them on the cliffs overlooking the river. Nearly 1,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured, including Baker, the only sitting U.S. senator ever to die in combat. When the Senate next convened on December 2, 1861, Oregon senator James M. Nesmith delivered a heartfelt eulogy recalling Baker’s impassioned debate with Breckinridge: “What he said as a Senator he was willing to do as a soldier.”

Within the Senate Chamber, the secession of the Southern states left a visible impact. When the Senate had convened at the start of the 37th Congress on March 4, 1861, the names of withdrawn senators whose terms had expired were ordered deleted from the Senate rolls. With the exception of Tennessee senator Andrew Johnson, who remained in the Senate after his state seceded, those Southerners whose terms continued simply stayed away. Some sent notices of withdrawal or announced their secession in local newspapers, but others just failed to appear. In July 1861 the Senate expelled 10 of the absent senators. In December it expelled Senator John C. Breckinridge, who had joined the Confederate army even though his home state of Kentucky remained in the Union. In January 1862 the Senate also expelled the two senators from Missouri, who sided with the Confederacy despite their state remaining in the Union. The final expulsion took place on February 5, 1862, when the Senate threw out Indiana senator Jesse Bright for promoting a constituent’s efforts to sell arms to the Confederacy.

The Capitol in Wartime

In just a few short weeks after the war began, Washington was transformed from a quiet capital to a city alive with the sounds of thousands of uniformed troops marching and drilling in the streets. The Capitol, with its recently added House and Senate wings and soon-to-be-completed cast-iron dome, took on “the appearance of an armed fort,” according to Washington writer Julia Taft Bayne. Building materials intended for the construction of the new dome were converted for use in fortifying the building. “About the entrance and between the pillars were barricades of iron plates intended for the dome, held in place by barrels of sand and cement,” Bayne wrote. Inside the building, the statuary and paintings were boarded up or draped in protective coverings.

As more troops arrived, conditions in the Capitol deteriorated. “Things are more unpleasant here every day,” Capitol architect Thomas Walter lamented, “every street, lane, and alley is filled with soldiers . . . the Senate Chamber is alive with lice; it makes my head itch to think of it—the bed bugs have travelled up stairs.” Isaac Bassett also worried about the damage being done to the ornate structure. “It almost broke my heart to see the soldiers bring armfuls of bacon and hams and throw them down upon the floor of the marble room,” he wrote. “Almost with tears in my eyes I begged them not to grease up the walls and the furniture.” On May 3, 1861, Walter complained in a letter to his wife about the atrocious conditions caused by the inadequate washing facilities in the Capitol: “There are 4000 [troops] in the Capitol with all their provision, ammunition and baggage, and the smell is awful. The building is like one grand water closet—every hole and corner is defiled . . . . The stench is so terrible I have refused to take my office into the building. It is sad to see the defacement of the building every where.”

Following the Second Battle of Bull Run in 1862, the Union army used the Capitol as a hospital for wounded troops, stirring sympathy among Capitol Hill personnel, but taking a toll on the building. In a letter dated September 2, 1862, Walter wrote:

The excitement here is very great and the presence of so many wounded greatly affect the sensibilities of all who have any feeling—poor fellows, what they must suffer. . . . They have taken the Capitol as a hospital, and the beds are now up in the rotunda, the old Hall of Rep’s, and the passages—one thousand beds have been put up. It does not interfere with our work in the least, and I think the move is a good one.

Walter’s assessment changed considerably over the next month. On October 3, as deteriorating conditions in the Capitol forced him to take his work outdoors, he wrote: “I am now writing in the middle of the street, with clouds of dust flying around me.” He lamented to a friend that he had been “compelled to move by the filth and stench, and live stock in the Capitol—there are more than 1000 sick and wounded in the building and it has become intolerable especially in the upper rooms.”

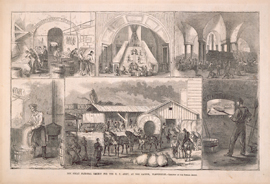

To meet the needs of the soldiers, the military quartermaster constructed large brick ovens in the basement of the Capitol. Several brick-walled rooms in the basement’s center section were quickly converted into a bakery to feed the troops. Interior staircases leading down to the new Capitol bakery were partially covered with planks so that huge barrels of flour could be rolled down into the basement. There were 14 ovens that baked 200 loaves a day, and another six or seven that produced 800 loaves a day. These larger ovens were located under the great steps on the west terrace of the Capitol. “The arcades under the flagway on the west side of the building are used for cooking,” commented the Washington Star, “and the smoke may be seen pouring out of the holes in the grassy slope.”

Feeding the troops became a well-organized activity. “When rations are to be served, the men pass in single file in the area along the series of arches,” continued the Star, “each with a tin plate and a tin cup. At the first archway two slices of freshly baked bread are handed to each man; at the next arch his allowance of meat, and at the next his coffee or soup, as the case may be.” While the troops and other occupants of the Capitol soon became accustomed to the aroma of baking bread, others worried about the conditions created by having such a large bakery housed in the Capitol. “I am pained to see a treasure instructed to my care—a treasure money cannot replace—receiving great damage from the smoke and soot that penetrates everywhere through that part of the Capitol which is under my charge,” wrote the librarian of Congress, John G. Stephenson, who worried about the threat of fire to his books that were housed in the Capitol.

When the Senate convened its emergency session in July 1861, and then returned for its regular session in December, soldiers quartered in the Capitol were forced to find another home, joining the thousands of troops occupying the city. “During the entire war Washington was a military camp,” Senator Sherman recalled in his memoirs. In fact, the city was surrounded by 68 forts and 22 batteries by war’s end, making it one of the most heavily fortified cities in the world. Sherman continued:

It was quite a habit of Senators and Members, during the war, to call at the camps of soldiers from their respective states. It was my habit, while Congress was in session during the war, to ride on horseback over a region within ten miles of Washington. . . . I became familiar with every lane and road, and especially with camps and hospitals. At the time it could truly be said that Washington was a great camp and hospital.

Despite the wartime emergency, work progressed on the new dome for the Capitol. The War Department announced on May 15, 1861, that it could not ensure funding for completion of the dome, but the workers agreed to continue without pay. At Clark Mills’s foundry, which was commissioned to cast Thomas Crawford’s Statue of Freedom for the top of the new dome, an enslaved man named Philip Reid was among those preparing this crowning symbol for the nation’s Capitol. Reid was one of many slaves who had labored in the construction of the Capitol. When the statue was finally placed atop the dome on December 2, 1863, Reid was a free man, liberated by the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act in 1862. The installation of the Statue of Freedom proved to be a symbolic event, signifying the enduring nation in a time of civil war. A battery of artillery fired a salute of 35 rounds, representing every state in the Union, including those of the Confederacy. The salute was then returned by the many forts surrounding the city of Washington.

Adapted from

The Senate's Civil War. Senate Historical Office. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2011.