When the framers of the Constitution gathered in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, they debated for months about how the new national legislature would be organized and function. How would its members be chosen and what qualifications would they have to fulfill? How large would the legislature be, and what would be the basis of its representation? What powers would it exercise?

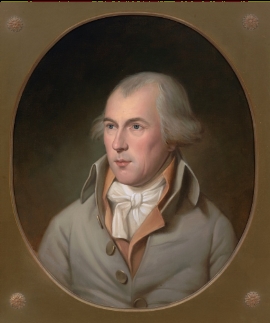

While these questions remained unsettled for weeks, the delegates in Philadelphia did enjoy a broad consensus on one aspect of the new Congress: it would be composed of two distinct bodies, a house and a senate. Drawing on ideas from ancient philosophers and Enlightenment thinkers, as well as recent experiences in crafting new state governments, the framers of the Constitution believed a bicameral legislature was crucial to creating and maintaining a stable republic. In particular, many of the framers argued that the key to a government that served the public good and protected the liberty of free citizens lay in the creation of a senate, which James Madison characterized as “the great anchor of the government.”1

In creating a senate, the framers were heavily influenced by the idea of mixed government, a concept rooted in ancient Greece and Rome. In the 4th century BCE, the philosopher Plato characterized three rival forms of government: monarchy (rule by the one), aristocracy (rule by the few), and democracy (rule by the many). Each system, in Plato’s view, could result in power wielded unjustly. Monarchy could turn into tyranny, aristocracy into oligarchy, and democracy into mob rule and anarchy. Although each order had its strengths—the monarchy energy, the aristocracy wisdom, and the people honesty—Plato posited that the best government was a mixed one that would balance the three social orders, with each exercising equal power in the process of making laws.2

American political thinkers of the revolutionary era frequently referenced classical history and philosophy and expressed the belief that a stable republic rested on the principles of mixed government. In 1772 John Adams, the most influential proponent of this idea, wrote, “The best Governments of the World have been mixed. The Republics of Greece, Rome, and Carthage were all mixed governments.” Adams and others did not have to look back to antiquity, however, to find a model of mixed government. For many, Britain provided the ideal system, with a monarch, the aristocratic House of Lords, and the democratic House of Commons. Americans understood their own colonial governments in a similar way, with power shared among a royal governor, a small advisory council, and an assembly elected by the colonists. If the British system had failed, many argued, it was because the balance among these orders had been destroyed—the king had corrupted Parliament and the colonial governments. As Americans created new state governments in the 1770s, their mission became “to correct the errors and defects” that plagued the British system.3

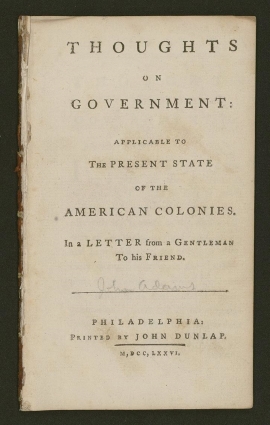

Proponents of mixed government argued that the stability of a republic required two separate legislative bodies. “I think a people cannot be long free, nor ever happy,” John Adams wrote, “whose government is in one Assembly.” The upper house had traditionally represented the aristocracy, but the United States lacked a titled nobility based on heredity and wealth. Many of the framers of state constitutions believed this role could be filled by a “natural aristocracy,” individuals who, in their view, possessed superior talents that brought them property and prominence. William Hooper of North Carolina, debating the constitution of his state in 1776, argued that in a single assembly, “A Warmth of Zeal may lead [representatives] into errors which a more cool, dispassionate enquiry may discover and rectify.” That dispassionate enquiry would come from those “selected for their Wisdom, remarkable Integrity, or that weight which arises from property and gives Independence and Impartiality to the human mind.” Benjamin Rush of Pennsylvania conceded in 1777 that the United States had “no artificial distinctions of men into noblemen and commoners,” but surely the states had individuals of “superior degrees of industry and capacity” that have “introduced natural distinctions of rank.”4

Ten of the original 13 states established bicameral legislatures with an upper house, identified either as a council or a senate. To establish these upper houses as distinct from the general assemblies, most states adopted higher property qualifications for those elected to the senate. Some states limited voting for senators to those with greater property. Maryland provided for indirect election of senators by a group of electors rather than by the people.5

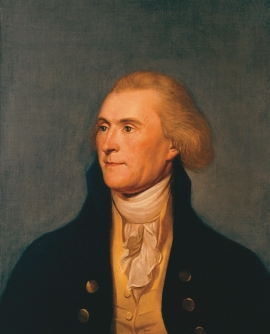

In the decade leading up to the federal constitutional convention, states that had not sufficiently balanced their democratic assemblies became a target of criticism. In his 1784 Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson complained that the Virginia senate was not designed to attract a different class of people from the assembly. “The senate is, by its constitution, too homogenous with the house of delegates. Being chosen by the same electors, at the same time, and out of the same subjects, the choice falls of course to men of the same description.” Jefferson argued that the two houses ought to “introduce the influence of different interests or different principles,” just as the British relied on the Commons for “honesty” and the Lords for “wisdom.” James Madison, in his Vices of the Political System of the United States, written in 1787 in anticipation of the constitutional convention, criticized the caliber of the individuals serving in state legislatures and accused them of passing “vicious legislation” that “prove[d] a want of wisdom” and threatened property rights. Pennsylvania’s powerful unicameral legislature received the most criticism. Rush called the Pennsylvania government “absurd” and an invitation to “mob government.”6

When the delegates to the federal convention arrived in Philadelphia, therefore, many of them were already convinced that the national government required a bicameral legislature to bring balance to what Virginia’s Edmund Randolph called the “turbulence and follies of democracy.” At the convention, some of the delegates went further, hoping to create a Senate that empowered America’s elite. John Dickinson of Delaware wanted the Senate “to consist of the most distinguished characters, distinguished for their rank in life and their weight of property, and bearing as strong a likeness to the House of Lords as possible.” Alexander Hamilton argued that society was naturally divided into the few and the many, and that each should have control over a portion of the government to prevent one from tyrannizing the other. He called for a Senate with members appointed to lifelong terms to allow the few to check the democratic passions of the many. Others argued that senators should earn no salary so as to attract only the wealthiest Americans.7

Although the completed Constitution submitted to the states for ratification stopped well short of creating an American House of Lords, it did set the Senate apart from the House in important ways. State legislatures would elect senators, thus producing the filter that framers believed necessary to select individuals with wisdom and independence. Longer terms of service for senators than for members of the House of Representatives as well as staggered elections would contribute to greater stability in the Senate, balancing the more democratic and ever-changing House. While the Constitution did not include property requirements for serving as a senator, jettisoning one of the ways in which states had identified the natural aristocracy, it did require senators to be older and have been naturalized citizens for longer than the members of the House.

Despite these stricter qualifications for senators, those who opposed the Constitution during ratification debates charged that the new government lacked the balance required of a proper mixed government. They argued that the proposed bicameral Congress placed power too distant from the people and laid the foundation for oligarchy. Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, writing as the Federal Farmer, believed that members of both the House and Senate would represent “an ever artful aristocracy.” The individuals in both houses would be too similar and too far removed from the “middling classes.” “The partitions between the two branches,” Lee held, “will be merely those of the building in which they sit.”8

Supporters of the Constitution applauded the separation of powers as defined in the new Constitution and embodied in the Senate. James Madison contended that the nation was not made up of rival social orders, nor did parts of the government represent distinct social orders. Each department of the government—legislative, executive, and judicial—derived its power from the people. That power was separated to prevent “those encroachments which lead to a tyrannical concentration of all powers of government in the same hands.” The legislative power was divided between “different bodies of men, who might watch and check each other” and thus “doubles the security of the people.” Madison acknowledged that the new Congress, especially the Senate, would be removed from the people, but he argued that this was the genius of the system. “In all civilized Countries,” he wrote,” the people fall into [many] different classes having a real or supposed difference of interests.” Congress’s purpose, Madison suggested, was to provide a forum wherein deliberation would allow representatives of the people to transcend narrow interests and arrive at laws that would serve the public good. The Senate, made up of “enlightened citizens,” was “necessary as a defense to the people against their own temporary errors and delusions” and would produce “the cool and deliberate sense of the community.” A sound government, he argued, required an “anchor against popular fluctuations.”9

The U.S. Senate is the product of political concepts both ancient and modern, reflecting established ideas about mixed government while pointing to new ways of thinking about the relationship between the people and their government. The Senate as established by the Constitution was created in an era of social and political transformation, and the beliefs about its role in the American system of government would continue to evolve. Over the next 233 years, the Senate moved farther away from its mixed government roots as the nation expanded, democratic sentiment grew among the people, and more groups demanded full participation in their government. The U.S. Senate continued, however, as a forum for deliberation and has remained a source of stability in an ever-changing nation.

Notes

1. "James Madison to Thomas Jefferson," October 24, 1787, in Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner, eds., The Founders’ Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), Volume 1, Chapter 17, Document 22, accessed September 9, 2021, https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch17s22.html.

2. Carl J. Richard, “The Classical Roots of the U.S. Congress,” in Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon, Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1994), 3–7; David J. Bederman, The Classical Foundations of the American Constitution: Prevailing Wisdom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 15–16.

3. John Adams, “Notes for an Oration at Braintree, Spring 1772,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed September 9, 2021, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-02-02-0002-0002-0001; Gordon Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), 197–214; Daniel Wirls and Stephen Wirls, The Invention of the United States Senate (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 11–38; Elaine K. Swift, The Making of an American Senate: Reconstitutive Change in Congress, 1787–1841 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 23–26.

4. "John Adams, Thoughts on Government," April 1776, in Kurland and Lerner, eds., Founders’ Constitution, Volume 1, Chapter 4, Document 5, accessed September 9, 2021, https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch4s5.html, quoted in Richard, “Classical Roots,” 12; "Benjamin Rush, Observations upon the Present Government of Pennsylvania," 1777, in Kurland and Lerner, eds., Founders’ Constitution, Volume 1, Chapter 12, Document 8, accessed September 9, 2021, https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch12s8.html, quoted in Wood, Creation of the American Republic, 246.

6. "Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia," 1784, in Kurland and Lerner, eds., Founders’ Constitution, Volume 1, Chapter 12, Document 11, accessed September 9, 2021, https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch12s11.html; James Madison, “Vices of the Political System of the United States, April 1787,” Founders Online, accessed September 9, 2021, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-09-02-0187; Benjamin Rush to Anthony Wayne, May 19, 1777, in L. H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 1:114–15, quoted in Wood, Creation of the American Republic, 233.

7. "Notes on the Debates in the Federal Convention, Thursday, June 7, 1787," Avalon Project, Yale Law School Goldman Law Library, accessed on September 9, 2021, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_607.asp; Alexander Hamilton, “Constitutional Convention, Speech on a Plan of Government, James Madison’s Version, [18 June 1787],” Founders Online, accessed September 9, 2021, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0098-0003; Richard, “Classical Roots,” 20–21.

8. "Federal Farmer, no. 11, January 10, 1788," in Kurland and Lerner, eds., Founders’ Constitution, Volume 1, Chapter 11, Document 12, accessed September 9, 2021, https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch11s12.html; "Federal Farmer, no. 4," October 12, 1787, in Kurland and Lerner, eds., Founders’ Constitution, Volume 4, Article 5, Document 5, accessed September 9, 2021, https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/a5s5.html; Wood, Creation of the American Republic, 483–99.

9. Jack Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Knopf, 1996), 228–39; “Term of the Senate, [26 June] 1787,” Founders Online, accessed September 9, 2021, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0044; James Madison, “The Federalist Number 48, [1 February] 1788,” Founders Online, accessed September 9, 2021, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0269; Madison, “The Federalist Number 10, [22 November] 1787,” Founders Online, accessed September 9, 2021, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0178; Wood, Creation of the American Republic, 430–67; James Madison, “The Federalist No. 62, [27 February 1788],” Founders Online, accessed September 9, 2021, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0212; Madison, “The Federalist Number 63, [1 March] 1788,” Founders Online, accessed September 9, 2021, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0312.