Of the 55 delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787, 19 of those constitutional framers later served in the U.S. Senate, including New York senator Rufus King. Like other consequential individuals whose participation in America’s founding crossed over into the new federal republic, King’s experience as a framer later informed his efforts to implement the Constitution as a member of Congress, bringing knowledge, continuity, and stability to the new government. A member of the Massachusetts delegation to the Constitutional Convention, King subsequently moved to New York and became one of the first two senators to represent that state in 1789. He went on to serve in the Senate longer than any other delegate to the Philadelphia convention—the Senate’s last framer—and became a respected and often outspoken elder statesman.

As historians have explained, the individuals chosen to attend the federal convention that resulted in the creation of a “partly federal and partly national” constitutional system “were not mere ‘theoretical’ politicians who were engaging in government for the first time.” They “were experienced veterans, many of whom had already been able to see the variants of democracy play out within their own states,” while others “knew firsthand the frustrations of governing” under the Articles of Confederation that preceded the constitutional government. This was certainly true of Rufus King.1

Just 32 years old when he attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787, King was already considered, as described by fellow delegate William Pierce of Georgia, a “man much distinguished for his eloquence and great parliamentary talents,” who “ranked among the Luminaries of the present Age.” Trained as a lawyer, he entered Massachusetts politics with service in the state’s general assembly before becoming a delegate to the Continental Congress. Taking leave of his post to attend the Philadelphia convention, King was present at every session and took notes—a valuable resource for historians. Considered “among the most capable orators” at the convention, his contributions were significant. He served on several major committees, including the important Committee on Postponed Matters and Committee of Style, which were charged with finalizing the document as the convention was ending. As historian Richard Welch concluded, King was “surely one of the most prominent members of the Convention at large.”2

After the ratification of the Constitution, when the First Congress convened in 1789, the 34-year-old King became the youngest senator of the time. King “came to the Senate with a record of solid achievement,” historian Roy Swanstrom explained, and he “was consistently among the most active Senators in committee work.” During his first Senate term, King played a key role in the creation and approval of the Jay Treaty, co-authoring with Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Chief Justice of the United States John Jay a series of published essays in defense of the controversial treaty with Great Britain. He also proved influential in establishing the First Bank of the United States and was elected one of the first 25 directors of the bank in 1791.3

In 1796 President George Washington appointed King to be minister to Great Britain, a position he held until 1803. Upon his return to the United States, King spent a decade out of public office before again being elected to the Senate in 1813. By this time, King was the “only senator who had sat in the body while Washington was President,” and was one of only two framers still serving in the Senate—along with New Hampshire’s Nicolas Gilman. When Gilman died in 1814, King became the last framer of the Constitution still serving in the Senate.4

Specializing in matters of finance and foreign relations, as well as maritime law, commerce, and public lands, King’s expertise was widely respected by his contemporaries. His skillful oratory often impressed his congressional colleagues, including a young, newly elected New Hampshire representative named Daniel Webster, who hailed King’s speaking ability as “unequalled.” When the Senate established its standing committee system in 1816, King was assigned to two of the most important panels—Foreign Relations and Finance. “In the years to come he would apply his knowledge and experience” to that committee work, noted a biographer, and “in debates and roll calls on the Senate floor, he was a watchdog, sniffling out signs of wastefulness and partisan aims.”5

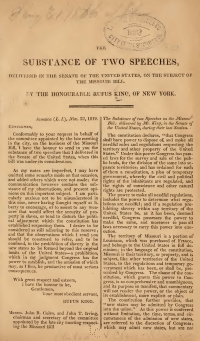

By the time the Senate tackled the difficult issue of the Missouri crisis in 1819 and 1820, King was a respected elder statesman. His status was tested, however, when the question of expanding slavery in new western states threatened to disrupt the delicate balance between slave states and free states, especially in the Senate, where states were given equal representation. King insisted that Congress had a right to exclude slavery from new states. This position alienated colleagues of slaveholding states but bolstered support in the northern states. King’s speeches rallied opposition to the proposed compromise that sought to admit Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state while prohibiting slavery in the territories north of the 36º 30' parallel.

King had consistently opposed the expansion of slavery throughout his career. While serving in the Continental Congress in the 1780s, he had introduced a resolution providing that there should be neither "slavery nor involuntary servitude" in the Northwest Territory, language that was ultimately incorporated into the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. During the Constitutional Convention, foreseeing the growing divide between slave and free states, he had expressed doubts about the three-fifths compromise that determined the method by which enslaved Americans were to be counted for purposes of taxation and representation. Although King had accepted the three-fifths compromise as a necessary concession to slaveholding states in order to gain adoption of the Constitution, by 1803, when the purchase of the vast Louisiana Territory raised new possibilities for the expansion of slavery, he believed that the three-fifths provision was one of the “greatest blemishes” on the Constitution.6

In 1819, as senators debated the issue of expanding slavery into Missouri and other western states, King stood in opposition, drawing on his participation in the constitutional debate over the three-fifths compromise to frame his argument. “The equality of rights, which includes an equality of burdens, is a vital principle in our theory of government,” he explained, “and its jealous preservation is the best security of public and individual freedom.” He maintained that “the departure from this principle in the disproportionate power and influence, allowed to the slave holding states” through the three-fifths compromise, “was a necessary sacrifice to the establishment of the constitution,” but such a compromise was no longer acceptable. “The effect of this concession has been obvious in the preponderance which it has given to the slave holding states over the other states.” He continued:

Nevertheless it is an ancient settlement, and faith and honour stand pledged not to disturb it. But the extension of this disproportionate power to the new states would be unjust and odious. The states whose power would be abridged, and whose burdens would be increased by the measure, cannot be expected to consent to it; and we may hope that the other states are too magnanimous to insist on it.7

King’s Senate speeches were printed and distributed as a pamphlet, fueling the already heated debate over slavery’s possible westward expansion. Given King’s status as a veteran statesman, the publication received much attention. According to historian Robert Ernst, “The speeches became a center of acrimonious controversy.” The pamphlet “has largely contributed to kindle the flame now raging throughout the Union on that question, and which threatens its dissolution,” John Quincy Adams (then serving as Secretary of State) wrote in his diary. “A whirlwind of anti-Missouri feeling swept over the North,” noted historian Homer Hockett. “Mass meetings were held and resolutions passed in open opposition to the extension of slavery into the new states,” commented historian Joseph L. Arbena, who wrote that “King appeared to be the source of much of this agitation.” His speeches and “ideas formed the bases for many of the essays, memorials, and speeches presented in support of his stand.” Observing King’s influence over the Missouri debate, Boston journalist and author William Tudor wrote to King in February 1820: “I have been convinced that it is chiefly owing to you that the nation has been awakened to examine its consequences.” Describing King’s fervor in the Missouri debate, Adams concluded, “King has made a desperate plunge into it, and has thrown his last stake upon the card.”8

While King’s speeches strengthened the opposition to the Missouri Compromise, they also stirred suspicions about the veteran senator’s motives. Critics, particularly those in favor of the compromise, accused King of using the crisis for his own political gain and to realign the parties around the issue and establish himself as a leader of a new party. Adams rejected such notions, arguing, “There is not a man in the Union of purer integrity than Rufus King.” Historians have tended to agree with Adams. “Although he would have welcomed a new political alignment of northern Republicans and the few remaining Federalists,” wrote Ernst, “there is no credible evidence that he plotted to bring this about, nor was he motivated by personal ambition for power.” Nevertheless, the suspicions cast upon King’s motives aided in diminishing the effectiveness of his influence upon the debate, contributing to the ultimate failure of his position.9

Despite the controversies of the Missouri crisis, King remained a respected and trusted public figure. In 1821 the Senate elected him as chairman of the influential Foreign Relations Committee—despite the fact that he was in the minority party, one of only four remaining Federalists in the Senate. Even those who had been disappointed by King’s position in the Missouri debate continued to hold him in high esteem. One admirer, Virginia representative John Randolph, remarked, “Ah, sir! only for that unfortunate vote on the Missouri Question, he would be our man for the Presidency. He is, Sir, a genuine English gentleman of the old school, just the right man for these degenerate times; but, alas! it cannot be.”10

King was both an ardent Federalist and an esteemed national leader whose link with the past, and particularly to his role as constitutional framer, garnered an admiration that eclipsed partisanship. “A venerable Senator, he was a sort of ‘Mr. Federalist,’" Ernst observed. Even as the Federalist influence declined, Ernst continued, “Rufus King's reputation as an elder statesman brightened.” His service in the Senate, which continued until 1825, extended well beyond any of the other 19 delegates to the Constitutional Convention who later became senators. A Massachusetts colleague, Harrison G. Otis, assessed the importance of King’s continuing service. “You prevent a great deal of mischief and keep in check the framers of crude projects and cunning devices,” Otis stated to King in 1823, adding, “whoever writes your epitaph…may be able to say that you continued many years at your post, the last of the Romans.” Rufus King, elder statesman, was the Senate’s last framer.11

Notes

2. “Notes of Major William Pierce on the Federal Convention of 1787,” The American Historical Review 3, no. 2 (January 1898): 325; National Park Service, Signers of the Constitution: Historic Places Commemorating the Signing of the Constitution (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976), 180–81; Richard E. Welch, Jr., “Rufus King of Newburyport: The Formative Years (1767–1788),” Essex Institute Historical Collections 96, no. 4 (October 1960): 267.

6. Welch, Jr., “Rufus King of Newburyport,” 248; Joseph L. Arbena, “Politics or Principle? Rufus King and the Opposition to Slavery, 1785–1825,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 101, no. 1 (January 1965): 64–65; Robert Ernst, “Rufus King, Slavery, and the Missouri Crisis,” The New York Historical Society Quarterly 46, no. 4 (October 1962): 364.

7. Rufus King, The Substance of Two Speeches, Delivered in the Senate of the United States, on the Subject of the Missouri Bill, (Philadelphia: Clark & Raser, printers, 1819), 6–7, Library of Congress collection, accessed on August 29, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/item/09020866/.

8. Ernst, “Rufus King, Slavery, and the Missouri Crisis,” 367; Charles F. Adams, ed., Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1875), vol. 4, 517, 526; Homer C. Hockett, "Rufus King and the Missouri Compromise,'' Missouri Historical Review 2 (April 1908): 216; Arbena, “Politics or Principle?” 72; Charles R. King, ed., The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King: Comprising His Letters, Private and Official, His Public Documents and His Speeches (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900), vol. 6, 272.