| Title | Henry Clay in the U.S. Senate |

| Artist/Maker | Phineas Staunton ( 1817 - 1867 ) |

| Date | 1866 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | Sight: h. 127.4375 x w. 82.875 in. (h. 323.6913 x w. 210.5025 cm)

Framed: h. 151 x w. 106 in. (h. 383.54 x w. 269.24 cm) |

| Credit Line | U.S. Senate Collection |

| Accession Number | 32.00050.000 |

As the Civil War drew to a close in 1865, the Kentucky state legislature launched a competition for a monumental 7 x 11 foot portrait of the great statesman Henry Clay to be displayed in the Kentucky state capitol. Although Clay's own son John voted in favor of Henry Clay in the U.S. Senate, the entry failed to win the competition. The painting was returned from Kentucky to the artist's hometown of LeRoy, New York. In 2006, the LeRoy Historical Society gave the painting and its original frame to the Senate. After undergoing conservation the monumental painting was installed in the U.S. Capitol.

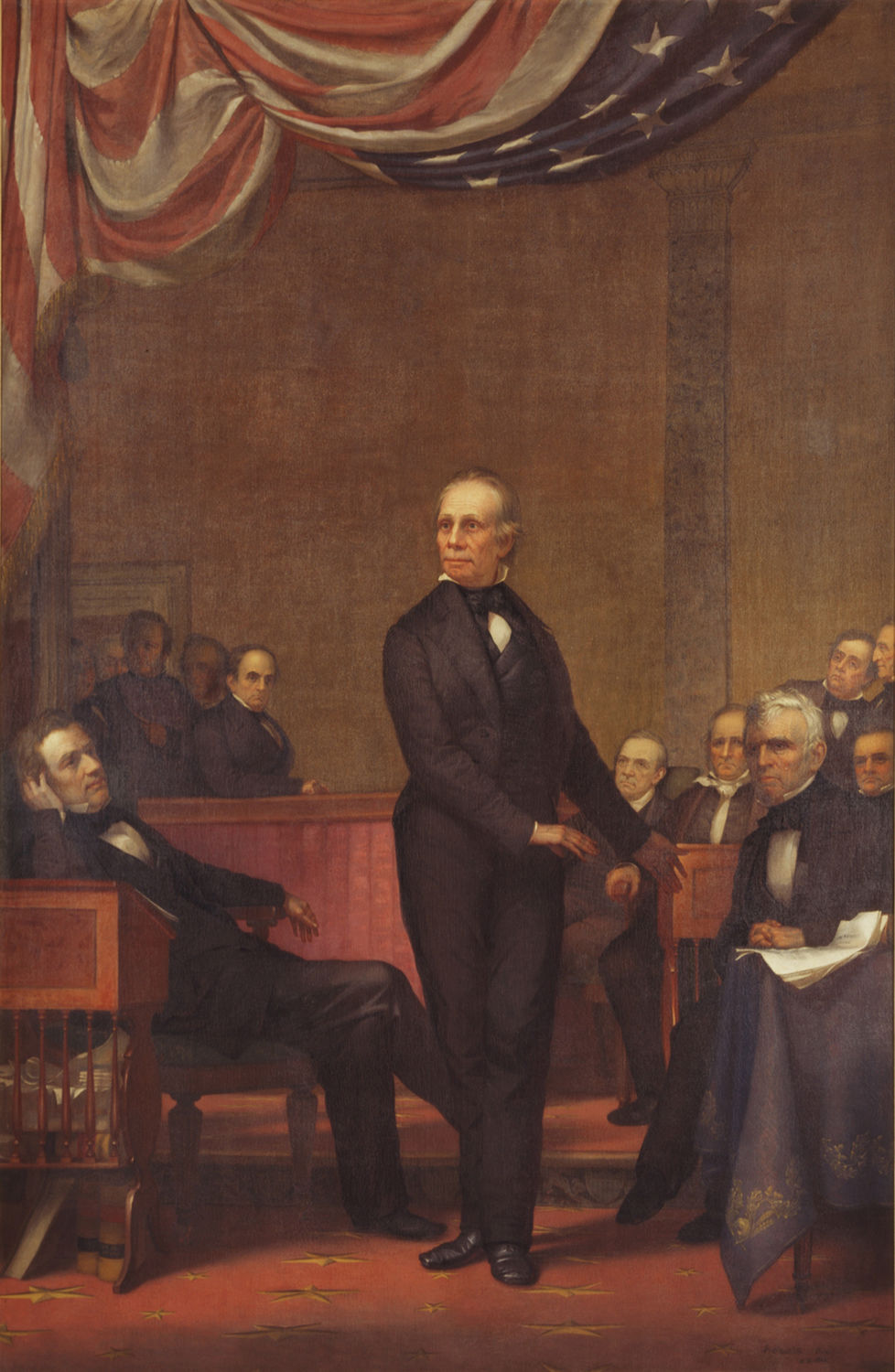

Henry Clay in the U.S. Senate memorializes Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky in the final months of his life. The figure of Clay gestures towards a document titled "In Senate, 1851." A leather-bound Senate journal in the painting's foreground indicates that this is the first session of the 32nd Congress, which ran from 1851 to 1853. Famed for his mellifluous voice, Clay stands nearly life size in the iconographic pose associated with the brilliant orator. He is surrounded by 12 friends and colleagues: (left to right) William Seward, R.M.T. Hunter, John Letcher, General Winfield Scott, George Robertson, Daniel Webster, Joseph Underwood, Sam Houston, John Crittenden, Lewis Cass, Stephen Douglas, and Thomas Hart Benton.

Henry Clay in the U.S. Senate is one of only three extant 19th-century paintings of the Old Senate Chamber, the room in which the Senate met from 1810 to 1859. There are no known photographs of the chamber, and only a few historic prints exist, so the painting provides valuable information about chamber's appearance in the era that led to the Civil War, often called the "Golden Age" of the Senate. Artist Phineas Staunton accurately depicts the furnishings, carpet pattern, and even the distinctive puddingstone marble columns of the chamber. It is likely that Staunton travelled to Washington and made studies of these items for an earlier portrait of Clay executed in 1847.

Phineas Staunton was born in 1817, the eldest son of a sheep and horse farmer in New York. He was a self-taught artist who registered in 1838 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts to study plaster casts and models for "improvement of drawing." Staunton enjoyed considerable success as a traveling portrait artist and also taught painting at Ingham University, a women's college founded by his wife in LeRoy, New York. During the Civil War, he joined the 100th Regiment of New York Volunteers. He served from 1861 to 1862 and obtained the rank of lieutenant colonel. Throughout his career, Staunton pursued portraiture, and executed several paintings of Henry Clay.

Staunton's life ended prematurely at age 49, just one year after he completed Henry Clay in the U.S. Senate. While accompanying a scientific expedition to South America and serving as its artist illustrator, he contracted yellow fever and died in Quito, Ecuador, on September 5, 1867.

The "Great Compromiser," Henry Clay, a native of Virginia, moved to Kentucky at the age of 20 and settled in Lexington. There he practiced law with great success, aided by his sharp wit and nimble mind. In 1806, after a stint in the Kentucky legislature, he was elected to fill the unexpired term of a U.S. senator who had resigned. Clay took the seat, although he was four months younger than the constitutional age requirement of 30. In 1807 he again was elected to the Kentucky legislature, where he eventually served as Speaker. Clay spent most of the years from 1811 to 1825 in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he was elected Speaker his first day in office. Almost immediately Clay made a name for himself as one of the warhawks, the young politicians who fueled anti-British sentiment and helped bring about the War of 1812. In 1814, he served as one of the commissioners negotiating the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war. During his years in the House, the well-respected Clay was elected Speaker six times.

It was during his time in the U.S. House that Clay urged that the United States become the center of an "American System," joined by all of South America, to wean the country away from dependence on the European economy and politics. He dedicated much of his career to a high protective tariff on imported goods, a strong national bank, and to extensive improvements in the nation's infrastructure.

In 1825, after an unsuccessful campaign for the presidency, Clay was appointed secretary of state under John Quincy Adams. He served in that position until 1829, and was subsequently elected to the U.S. Senate. From 1831 to 1842, and again from 1849 to 1852, Clay distinguished himself as one of the Senate's most effective and influential members.

Clay earned the sobriquet "Great Compromiser" by crafting three major legislative compromises over the course of 30 years. Each time, he pulled the United States from the brink of civil war. In 1820 and 1821, he used his role as Speaker of the House to broker the Missouri Compromise, a series of brilliant resolutions he introduced to defuse the pitched battle as to whether Missouri would be admitted to the Union as a slave state or free state. Although he owned slaves himself, Clay anguished about slavery, which he called a "great evil." He believed slavery would become economically obsolete as a growing population reduced the cost of legitimate labor. Under Clay's compromise, Missouri was admitted as a slave state and Maine as a free state.

In 1833 Clay's skill again was tested when South Carolina passed an ordinance that nullified a federally instituted protective tariff. Although President Andrew Jackson urged Congress to modify the tariff, he threatened to use federal troops against South Carolina if the state refused to collect it. Despite a long-standing enmity toward Jackson and with a deep commitment to high tariffs, Clay ended the crisis by placating both sides. He introduced a resolution that upheld the tariff but promised its repeal in seven years.

The argument over slavery flared once again in 1850 when Congress considered how to organize the vast territory ceded by Mexico after the Mexican War. As in 1820, Clay saw the issue as maintaining the balance of power in Congress. His personal appeal to Daniel Webster enlisted the support of that great statesman for Clay's series of resolutions, and civil war was again averted.

Clay died in 1852. Despite his brilliant service to the country and three separate campaigns, he never attained his greatest ambition—the presidency. A man of immense political abilities and extraordinary charm, Clay won widespread admiration, even among his adversaries. John C. Calhoun, whom he had bested in the Compromise of 1850, once declared, "I don't like Clay. . . . I wouldn't speak to him, but, by God! I love him." [1]

1. Robert V. Remini, Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union (New York: W.W. Norton, 1991), 578.