The Road to War

Conflict and Compromise

Sectional disputes dominated debate during the period between the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850 and brought to the Chamber a group of talented legislators and powerful orators. In the Senate, where the Constitution established an equality of states, there existed a delicate balance between North and South, slave and free states. For many years, senators crafted legislation designed to resolve sectional conflicts and avoid secession and civil war. In the 1850s, however, further efforts at compromise failed. The Senate endured a violent and turbulent decade that propelled the nation to the brink of war.

The rapid expansion of the nation, as settlers moved west and new territories applied for statehood, repeatedly raised the issue of slavery. The Constitution allowed slavery to exist in the states but left Congress to decide its status in the territories. The Northern states, having abolished slavery, sought to prevent its spread, while the Southern states, having grown more dependent on slave labor, asserted the rights of Southerners to transport their way of life into the new territories. In 1820 the Missouri Compromise drew a line across the nation at the 36th parallel, above which slavery would be prohibited, and below which it could expand. When the war with Mexico, from 1846 to 1848, resulted in vast new territories in the southwest, the debate over expansion of slavery was renewed.

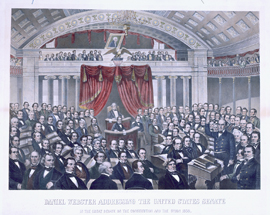

In 1850 Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky introduced a package of compromise measures to relieve the sectional tensions created by territorial expansion. Aware of the controversial nature of his proposals, Clay urged his colleagues to “beware, to pause, to reflect before they lend themselves to any purposes which shall destroy that Union.” On March 7, 1850, Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts rose from his Senate seat and declared: “I wish to speak today, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American . . . I speak today for the preservation of the Union.” Other senators, most notably John Calhoun of South Carolina, opposed Clay’s plan. With Webster’s support, and with the assistance of Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, Congress passed revised versions of Clay’s bills, which became law in September 1850. The Compromise of 1850 admitted California as a free state, left open the possibility of slavery in the territories of New Mexico and Utah, abolished the slave trade in the District of Columbia, and created a stronger fugitive slave law.

Anxious to build a transcontinental railroad from Chicago to the West Coast, Senator Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 to organize those territories for statehood. To meet the objections of Southerners who were promoting a southern route for the railroad, the act opened the territories for settlement, but provided that the settlers, through “popular sovereignty,” could allow or prohibit slavery. This undermined the 1820 Missouri Compromise and further inflamed the passions in the North and the South. Both slaveholders and abolitionists flooded into the new territories to influence votes on state constitutions. Communities erupted into violence in what became known as “Bleeding Kansas.” Intended to settle sectional disputes, the Kansas-Nebraska Act instead brought the nation closer to civil war.

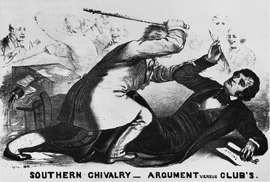

In May 1856 Senator Charles Sumner, a fiery abolitionist from Massachusetts, delivered a five-hour oration in the Senate Chamber entitled “The Crime Against Kansas.” Sumner’s inflammatory speech was a harsh indictment of those who supported the spread of slavery and attacked several senators by name, including Andrew Butler of South Carolina. On May 22, 1856, Preston Brooks—a member of the House of Representatives and Senator Butler’s relative—retaliated. After the Senate had adjourned for the day, Brooks approached Sumner at his desk in the Senate Chamber and repeatedly struck him on the head with his heavy walking stick, breaking the wooden cane into pieces. Badly injured by the attack, Sumner was able to appear in the Senate only intermittently over the next three years, as he slowly recovered. His empty desk became visible evidence that legislative compromise could no longer settle the emotional and divisive issue of slavery in the territories.

An era in Senate history ended when the Senate held its last session in its venerable old Chamber. The rush of states entering the Union had doubled the number of senators and forced them to authorize construction of a new, larger Chamber. On January 4, 1859, senators marched in procession from the old Chamber—so associated with the Great Triumvirate of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John Calhoun—to the new Chamber in the Capitol’s north wing. In that procession walked men who would soon be leaders of the Union and the Confederacy.

Secession

The presidential election of 1860 saw a split in the Democratic Party between its northern and southern wings, and the rise of the new Republican Party. The northern Democratic senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois ran against a southern Democrat, Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, and against the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, whom Douglas had defeated for a Senate seat just two years earlier. A fourth candidate, former Whig senator John Bell of Tennessee, ran as the Constitutional Union candidate. In this divided field, Lincoln won the election on November 6, 1860. Four days later, Senator James Chesnut of South Carolina resigned his Senate seat. Although no state had yet seceded from the Union, rumors of secession were heard everywhere. Chesnut “burned his bridges” in the Senate, noted his wife Mary, and returned to South Carolina to draft an ordinance of secession and attend the first Confederate Congress. The next day, his fellow South Carolinian, Senator James Hammond, submitted his own resignation and turned his attention to establishing the Confederacy, which he pledged to support “with all the strength I have.” On December 20 South Carolina voted to secede from the Union, followed by another 10 states over the next six months.

The month of January 1861 proved to be particularly painful for the Senate. On January 9 Mississippi became the second state to secede. This action prompted Senator Jefferson Davis to address the Senate on January 10, imploring his colleagues to allow for peaceful secession of the Southern states. “If you desire at this last moment to avert civil war, so be it,” Davis proclaimed. “If you will not have it thus . . . then, gentlemen of the North, a war is to be inaugurated the like of which men have not seen. . . .” On January 21, as a packed and tearful gallery of spectators watched, Davis bid farewell to the Senate. In his final address, he warned that interference with Southern secession would be disastrous.

![]()

I am sure I feel no hostility to you, Senators from the North. I am sure there is not one of you, whatever sharp discussion there may have been between us, to whom I cannot now say, in the presence of my God, I wish you well . . . . I hope . . . for peaceful relations with you, though we must part. . . . The reverse may bring disaster on every portion of the country . . . . Mr. President, and Senators, having made the announcement which the occasion seemed to me to require, it only remains for me to bid you a final adieu.

On February 18 Davis became president of the Confederate States of America. By that time, 7 of the 11 Confederate states had already seceded. (Tennessee became the last to withdraw, on June 8, 1861.) When crowds gathered at the Capitol on March 4, 1861, to witness Lincoln’s first inauguration, the nation was already divided and preparing for war.

During the months between Lincoln’s election and his inauguration, many members of Congress clung to the hope of reconciliation. Kentucky senator John J. Crittenden led a last-ditch effort at compromise, proposing to extend to the Pacific Ocean the line established by the 1820 Missouri Compromise. The proposal failed. Senator Charles Sumner dismissed such compromise efforts as a misreading of the secession movement, “deeming it merely political & governed by the laws of such movements, to be met by reason, by concession, & by compromise; whereas it is a revolution.”

Adapted from

The Senate's Civil War. Senate Historical Office. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2011.