The Christmas season often brings a sense of joyous anticipation as people celebrate the holiday, enjoy family gatherings, and eagerly await the opening of gifts. Would that special “something” be under the tree? In 1932 that “something” on many people’s wish list was beer.

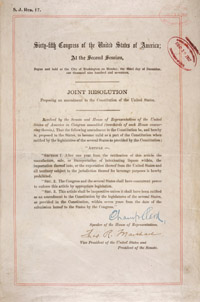

The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in December 1917 and ratified by the states in January 1919, banned the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” To enforce the amendment, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act (named for its sponsor, Representative Andrew Volstead of Minnesota), in October 1919. Passed over a veto by President Woodrow Wilson, the Volstead Act defined an “intoxicating beverage” as anything that contained more than .5 percent alcohol. While much of the campaign against alcohol in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had focused on hard liquor, the act’s strict definition also outlawed beer and wine.1

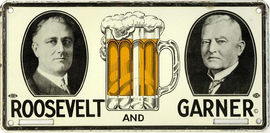

After a decade of Prohibition and the challenges of enforcement—even in the halls of Congress—American politicians in the 1920s split between the “drys,” who wanted to maintain Prohibition, and the “wets,” who wanted it repealed. Both political parties were internally divided over the issue and for more than a decade refrained from adopting a national stance on the question of alcohol. In 1932, however, with the nation suffering through the Great Depression, the Democrats adopted a party platform that supported repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment and modification of the Volstead Act to allow for the manufacture of beer. The Republicans stopped short of endorsing repeal that year—their party platform stated the issue “was not a partisan political question”—but did support altering the amendment to allow states to decide the issue for themselves.2

With Franklin Roosevelt’s victory in the 1932 presidential election and Democratic majorities elected to the House and Senate, many believed that the end of the Prohibition Era was imminent. The election had been largely a referendum on economic issues, but popular majorities throughout the country had expressed support for legalizing alcohol again. In the November election, nine states voted to repeal their Prohibition statutes, and two others approved referenda supporting national repeal. Elected officials, including Louisiana senator Huey Long, began to state optimistically that Congress might deliver “beer by Christmas.” Throughout the country, beer producers, pubs, and taverns quietly made preparations in anticipation of serving beer by December 25.3

As Congress returned for a lame-duck session in December, which would last until March 4, 1933, the “wets” arrived in Washington ready to act. Speaker of the House John Nance Garner, soon to be Vice President Garner, made repeal of the Prohibition amendment the first order of business, but on December 5 Garner’s resolution fell six votes short of the necessary two-thirds majority. The “drys” had won that round, but the “wets” did not concede defeat. “Congress will legalize some sort of beer before Christmas,” Garner announced.4

House Democrats had already held meetings in November before the opening of the session, including with President-elect Roosevelt, and scheduled committee hearings for December 7 to consider a beer bill. Representative James Collier, chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, drafted a bill to legalize beer containing less than 2.75 percent alcohol, which he deemed “non-intoxicating.” Collier’s bill also provided for taxation of beer sales, which allowed supporters to emphasize that legalization would provide badly needed revenue to the federal government in the face of growing budget deficits. Beer producers urged the House to increase the allowable alcohol content to 3.2 percent and promised that they could employ 300,000 people and provide the government with $400 million in revenue over the next year.5

Despite a sense of urgency, the House committee did not report the bill until December 15, and another week passed before the House passed the bill on the 22nd. The prospect of “beer by Christmas” was now in the hands of the Senate. Could the Senate act quickly enough to make the Christmas deadline?6

On December 23, the Senate referred the Collier bill to the Judiciary Committee. Since it included a beer tax, the bill also went to the Finance Committee. With time running out, Republican senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut—who had just lost his re-election campaign and was now a lame-duck senator—attempted to bypass the committees and get quick action. Bingham had introduced his own beer bill at the start of the previous session of Congress. The Committee on Manufactures had considered his bill but reported it to the full Senate with the recommendation that it not pass. Despite the adverse report, the bill was still available on the Senate calendar. Believing that the political situation had changed, Bingham moved to call up his bill. He intended to amend it by substituting the bulk of the Collier bill for his, predicting the amended bill would promptly pass the Senate.7

When Bingham made his motion to proceed to his bill, however, Democratic Leader Joseph Robinson of Arkansas—soon to be majority leader—applied the brakes. Would any beer, even 3.2 percent beer, be constitutional under the Eighteenth Amendment, Robinson pondered? He insisted that the decision required more careful attention and should not be made with “undue haste.” As the popularity of repeal grew nationwide and Democrats prepared to take the majority on March 4, partisan gamesmanship was also at play. Robinson charged the Republican Bingham of attempting to “embarrass” and upstage the Democrats. As one reporter wrote, “The Democrats let it be known that they had no intention of letting a Republican lame duck steal both the show and the beer bill.” Consequently, Bingham watched his motion fail by a vote of 23–48. Frustrated, he complained that America wouldn’t see beer even by Valentine’s Day.8

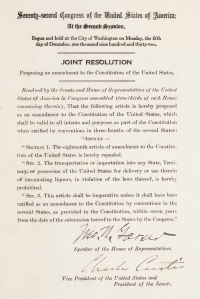

Beer would not flow by Christmas or even by the end of the 72nd Congress, but in February of 1933 both houses of Congress approved a constitutional amendment to repeal Prohibition. While the country awaited ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment (which came in December 1933), the House and Senate convened the 73rd Congress on March 4 ready to act. On March 22, 1933, Congress passed the bill to legalize beer with an alcohol content of 3.2 percent or less. Within an hour, the bill was on President Roosevelt’s desk. Always in tune with public opinion, Roosevelt signed it into law and then reportedly remarked: “I think this would be a good time for a beer.”9

Notes

7. A bill to amend the National Prohibition Act, as amended and supplemented, in respect to the definition of intoxicating liquor, S. 436, 72nd Cong., 1st sess., December 9, 1931; Senate Committee on Manufactures, Amendment of the Prohibition Act, S. Rpt. 72-635, 72nd Cong., 1st sess., May 3, 1932; “Bingham to Ask Vote in Senate on Beer Today,” Washington Post, December 23, 1932, 1.