| 202409 05The Senate and the 1994-95 Baseball Strike

September 05, 2024

On August 12, 1994, members of the Major League Baseball Players Association began a strike—the threat of which had been hanging over the sport all summer—and nobody knew just how long it would last. Negotiations had stalled on a collective bargaining agreement between owners and players. Given the heated rhetoric on both sides of the dispute, it seemed highly unlikely that a resolution would develop anytime soon. As it turned out, the 1994 baseball strike led to a cancelled World Series, millions of heartbroken fans, and a series of bipartisan efforts by United States senators to save America’s pastime.

At approximately 11:28 p.m. on August 11, 1994, Ricky Jordan strode to home plate, bat in hand, hoping to win the game for the Philadelphia Phillies. It was the bottom of the 15th inning, two outs, and the score knotted 1-1 against the rival New York Mets. Mauro Gozzo toed the rubber; Jordan readied in his stance. A second later, the crack of Jordan’s bat sent a ground ball into left field and the Phillies to a 2-1 victory, the type of ending that seemed to only happen in the movies.1

The Phillies crowd, 37,605 strong, should have been elated, but the response was oddly tempered for good reason. They—and every other baseball fan for that matter—knew there would be no baseball the next day. Baseball players were set to strike starting August 12, a reality that had been hanging over the sport all summer, and nobody knew just how long it would last. An accurate assessment of public sentiment came just after the Phillies game from star player Lenny Dykstra: “Dude, this really sucks.”2

The 1994 Major League Baseball (MLB) season had begun under ominous circumstances. The league’s collective bargaining agreement (CBA) signed with the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) had expired on December 31, 1993. Games continued in the spring of 1994 even while negotiations stalled. Club owners delivered their first proposal to the MLBPA on June 14, which the players summarily rejected. A month later, with the two sides no closer to an arrangement, the MLBPA announced that if an agreement was not reached by August 12, players would strike. August 12 arrived and, with no deal in place, all games were canceled. Given the heated rhetoric on both sides, it seemed highly unlikely that an agreement would develop anytime soon. As it turned out, the 1994 baseball strike led to a cancelled World Series, millions of heartbroken fans, and a series of bipartisan efforts by United States senators to save America’s pastime.3

Congressional Action

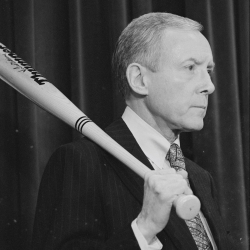

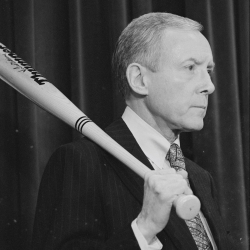

Senator Howard Metzenbaum, a Democrat from Ohio who chaired the Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies, and Business Rights, watched intently as the 1994 baseball season collapsed. His subcommittee had been exploring problems in professional baseball for several years, specifically the sport’s antitrust exemption, a legal arrangement stemming from a 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case that determined that the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which prohibited monopolistic business practices, did not apply to Major League Baseball. The Court’s ruling had broad implications, but it primarily meant that professional baseball players and umpires were not afforded the same legal protections as those in other professional sports. When it came to labor disputes, a strike was the only available negotiation tactic. The Supreme Court heard multiple cases between 1922 and 1994 challenging baseball’s antitrust exemption, yet the majority consistently upheld the original ruling while noting that Congress could pass legislation at any time to repeal the exemption.4

Since the 1950s, Senate committees had periodically held hearings on the economics of professional sports, but the baseball antitrust exemption had largely escaped close scrutiny. That ended in December 1992 when Metzenbaum’s subcommittee held a hearing regarding “the validity of MLB’s exemption from the antitrust laws.” In his opening statement, Chairman Metzenbaum asserted that Major League Baseball had become “a legally sanctioned, unregulated cartel.” During the hearing, other committee members expressed their belief that baseball club owners did not look out for the interests of fans, especially since the league had not hired a new commissioner after ousting Fay Vincent from that role earlier in 1992. Without a commissioner to manage the league, some senators argued that professional baseball essentially had no oversight in light of the antitrust exemption and that Congress had a duty to fill that role.5

Both Metzenbaum and the subcommittee’s ranking member, Republican Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, hammered baseball team owners on the issue. “The implications for fans are ominous,” Senator Metzenbaum observed. “Every time there has been a labor negotiation in baseball, there has been either a strike or a lockout.” Senator Thurmond argued professional baseball’s current structure was so outdated that, were it proposed in 1992, it would be “laughed out of the Hart [Senate] Office Building.” Other senators hedged on what they considered the radical step of repealing the antitrust exemption. Republican senator Orrin Hatch of Utah warned that doing so could have unknown consequences. Democratic senator Dianne Feinstein of California, in a joint statement with Senator-elect Barbara Boxer of California, argued the exemption was needed to protect cities from arbitrary franchise relocation because “baseball is not a product like a box of Tide that can be sold in a supermarket…. Baseball is part of the fabric and unity of the American city.” Feinstein furthered that baseball was not a business but an American tradition and should maintain the antitrust exemption.6

More than a year later, on March 4, 1994, with spring training underway and negotiations for a collective bargaining agreement stalled, Senator Metzenbaum introduced the Professional Baseball Antitrust Reform Act to revoke baseball’s antitrust immunity. Six Democrats and three Republicans co-sponsored the bill. The subcommittee held a hearing on the legislation on March 21, 1994, five months before the strike would begin. In an effort to maximize public attention, Metzenbaum held the hearing at the Bayfront Center arena in St. Petersburg, Florida, directly across the street from the historic Al Lang Stadium, where spring training games took place. Metzenbaum did not mince words, calling the league an “overprivileged owners’ cartel” while calling for Congress to “reclaim our national pastime for the fans before the barons of baseball become too cozy, too comfortable, and too cocky.” Despite his efforts, the full Judiciary Committee voted down Metzenbaum’s bill 10 to 7 on June 23, 1994, effectively ending Senate intervention for the time being. The bill’s opponents felt uneasy about interfering in ongoing labor negotiations as well as the unintended consequences that the legislation could have on other labor unions going forward.7

Throughout the 1994 summer, legislators stayed mostly quiet on the pending baseball strike, but behind the scenes, many crafted legislation that would, if necessary, return players and fans to ballparks. Senators may have been reluctant to confront the antitrust exemption, but a growing consensus was emerging that action should be taken to address a strike. Once the August 12 strike ultimatum arrived, a bipartisan group of senators, led by Metzenbaum, Thurmond, Hatch, and Democrat Patrick Leahy of Vermont, initiated what would become Congress’s most direct intervention between sports and labor.8

The Strike Begins

As the players’ strike began on August 12, senators continued to grapple with the question of what role, if any, Congress should play in a private labor dispute. “The real message should be a wake-up call to baseball,” Senator Hatch commented. “If you do not want Congress to be involved, then settle this dispute yourself.” Democratic senator Dennis DeConcini of Arizona pointed out that “the Government is already involved [in baseball] and has, in effect, created a baseball monopoly.” “In other instances where we create a monopoly,” he observed, “such as utilities, no one questions the Government’s authority to regulate.” Most senators who favored action wanted to target the antitrust exemption. MLBPA leader Donald Fehr had, in fact, informed Senator Metzenbaum that players would end the strike—thus saving the 1994 season—if Congress ended the antitrust exemption.9

Senators who opposed congressional action, such as Republican David Durenberger of Minnesota and Democrat Harris Wofford of Pennsylvania, argued that it would be bad precedent for Congress to intervene in strikes and that revoking the antitrust exemption would damage the economic fortunes of minor league teams and MLB teams in smaller markets. Pennsylvania Republican Arlen Specter suggested that Congress could offer no solution beyond encouraging arbitration.10

Meanwhile, a nightmare befell baseball fans when on September 14, 1994, Milwaukee Brewers owner and now acting commissioner Bud Selig announced the World Series was cancelled for the first time in 90 years. Two weeks later, Senators Metzenbaum and Hatch, who now favored antitrust legislation in part due to the strike, revived antitrust legislation for an 11th-hour floor vote, but it was blocked by Nebraska senator J. James Exon on grounds that it would “set a bad precedent” and that “this is not the proper time or action for the Senate to become involved in the matter of professional baseball.” The amendment was then withdrawn, one of Senator Metzenbaum’s final Senate acts before his retirement. Throughout the winter of 1994–95, all negotiations failed, including proposals put forth by both the White House and the House of Representatives.11

The 104th Congress

When the 104th Congress convened on January 4, 1995, senators watched while President William J. Clinton summoned MLB and MLBPA leaders to the White House. If a settlement was not reached by February 7, Clinton announced, he would issue recommendations to Congress for legislative action. As expected, the president’s deadline passed with no resolution. Senate Majority Leader Robert J. “Bob” Dole of Kansas explained he was “very, very reluctant” to intervene with legislation, and the Wall Street Journal reported that Congress would offer “nonlegislative support” as it further deliberated the antitrust exemption.12

When the owners indicated they would begin the 1995 season by hiring non-union, replacement players—a tactic used by the National Football League in 1987—lawmakers renewed their efforts to force a deal. Senator Metzenbaum’s retirement meant the Senate had lost a powerful voice in the baseball fight, but several others stepped up to the plate. In early February 1995, Democratic senator Edward M. “Ted” Kennedy of Massachusetts introduced legislation drafted by the White House that would establish a dispute resolution panel to impose a binding agreement on the players and owners. Kennedy implored his colleagues, “The question is who speaks for Red Sox and millions of other fans across America. At this stage in the deadlock, if Congress does not speak for them, it may well be that no one will.” Meanwhile, Judiciary Committee chairman Hatch worked with Democratic senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York on a new antitrust bill, while Senators Thurmond and Leahy simultaneously collaborated on their own antitrust legislation.13

Two bills that would repeal baseball’s antitrust exemption emerged from this work—the Hatch-Moynihan and Thurmond-Leahy bills—and both were introduced on February 14, 1995. Donald Fehr had privately informed Hatch days earlier that the MLBPA would end the strike were the Hatch-Moynihan bill to pass. Senator Thurmond’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Business Rights, and Competition held hearings on both bills one day after their introduction, with members still debating whether to intervene. Leahy argued that “there is a public interest in the resumption of true, major league baseball”—a dig at replacement players—and advocated for Congress to finally establish an antitrust regulatory framework. Republican senator Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas, who opposed intervention, argued that “absent a national emergency,” legislation would set “a very dangerous precedent.” Senator Howell Heflin of Alabama, a Democrat, agreed, noting the unknown effect such legislation may have upon “the price of baseball overall—players’ salaries, owners’ money, the division, whatever.” Senator Thurmond argued that baseball’s antitrust exemption should be revoked regardless of the strike, the same position he held in 1992.14

Acting commissioner Bud Selig testified at the hearings alongside Donald Fehr and star players Eddie Murray and David Cone. Murray vented his frustrations with the antitrust exemption: “Should fire codes not apply to stadiums because baseball is unique? Should health codes not apply to hot dogs sold in baseball stadiums? Should civil rights not apply to baseball? It sounds stupid to me, but why does the antitrust exemption make any difference?” Selig warned that Major League Baseball faced a dire financial situation, which would only be exacerbated by congressional intervention. Selig further claimed that the antitrust exemption was “irrelevant in the labor area” and only affected franchise relocation and minor league baseball. In response to Selig’s position, Senator Moynihan remarked that if “the owners believe [the antitrust exemption] is irrelevant to the strike…then they shouldn’t mind if we repeal it.”15

After the hearings ended, senators put neither bill to a vote, hoping that a CBA settlement would soon be reached. However, negotiations continued to falter into late March. With the MLB season’s opening day with replacement players just days away, Senators Hatch, Thurmond, and Leahy introduced a unified compromise bill with the co-sponsorship of Senators Moynihan and Bob Graham of Florida. This action came just one day after the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) made a player-friendly ruling on the dispute. The MLBPA again made it publicly known that players would return to the field if either the bill passed or a federal court issued the injunction sought by the NLRB.16

As Congress deliberated, a federal court intervened. On March 31, 1995, just days before the 1995 season would have normally begun, U.S. District Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor issued the injunction sought by the NLRB, effectively ending the strike. While not a long-term solution, the injunction broke the gridlock and returned players and fans to America’s professional baseball fields.17

The Curt Flood Act

The drama surrounding the Senate’s legislative efforts dissipated once baseball players returned to the diamond in April 1995, but the group of senators who wanted to end baseball’s antitrust exemption continued to press the issue. Senators Hatch, Leahy, Thurmond, and Moynihan reintroduced similar legislation in the 105th Congress, though this time it bore the name the Curt Flood Act of 1997.18

Naming the bill after Flood was timely and appropriate, as Senator Leahy noted, given Flood’s sacrifice and legacy in challenging baseball’s economic system. Curt Flood, an all-star outfielder for the St. Louis Cardinals, had filed a historic lawsuit against the MLB in 1969 over perceived contractual mistreatment, thereby challenging the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1922 ruling that established baseball’s antitrust exemption. On January 3, 1970, famed broadcaster Howard Cosell questioned Flood on ABC’s Wide World of Sports: “What’s wrong with a guy making $90,000 being traded…those aren’t exactly slave wages.” Flood, an African American, quipped, “A well-paid slave is nonetheless a slave.” Flood willingly chose this unprecedented action in an effort to better the economic conditions of not just himself, but all professional ballplayers. However, two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld baseball’s antitrust exemption in Flood v. Kuhn (1972) despite admitting the apparent “inconsistency or illogic" within the original 1922 decision. After filing his lawsuit, Flood played in just 13 games; his professional career was over. Blackballed from professional baseball, Flood retired to private life where he worked as a sportscaster and business owner while also painting portraiture. He died on January 20, 1997, at the age of 59. Upon Flood’s death, senators honored his effort on behalf of baseball players by naming the legislation after him.19

Importantly, the Curt Flood Act included significant legislative compromises, which helped it overcome hurdles faced by earlier legislative attempts. It explicitly excluded minor league baseball from its purview, thus alleviating concerns from minor league owners and some senators who had opposed earlier bills. After another round of hearings and input from the MLBPA and club owners, the Curt Flood Act passed the Senate by unanimous consent on July 30, 1998, and the House by voice vote on October 7. President Clinton signed it into law less than three weeks later. Though affecting only major league players, it marked the first time that Congress established a legislative solution to the Supreme Court’s 1922 antitrust ruling. As Senator Leahy noted in his floor remarks on the bill, “The certainty provided by this bill will level the playing field, making labor disruptions less likely in the future. The real beneficiaries will be the fans. They deserve it.”20

The 1994 baseball strike was the most impactful sports labor stoppage in U.S. history when measured by games cancelled, lost revenue, and congressional response. The Curt Flood Act, while years in the making, demonstrated bipartisan efforts by senators to correct what was, in their view, an unjust reality for major league baseball players. The bill’s impact is still being measured, but it did empower, in theory, individual MLBPA members to file suit like Curt Flood did in 1969. This bill also brought Curt Flood, a name largely forgotten to all but the most ardent of baseball fans, back into public discourse. Minutes before the Senate passed the Curt Flood Act, Senator Leahy concluded, “When others refused, [Curt Flood] stood up and said no to a system that he thought un-American.…I am sad that he did not live long enough to see this day.”21

Notes

1. “Philadelphia Phillies 2, New York Mets 1,” Retrosheet, https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1994/B08110PHI1994.htm.

2. Tim Kurkjian, “’Oh my God, How Can We Do This?’: An Oral History of the 1994 MLB Strike,” ESPN, Aug. 12, 2019; Kevin Kaduk, “August 11, 1994: Scenes from a Lost MLB Season,” Yahoo Sports, Aug. 9, 2019, accessed August 28, 2024, https://sports.yahoo.com/august-11-1994-scenes-from-a-lost-season-042806980.html.

3. Paul Staudohar, “The Baseball Strike of 1994-5,” Monthly Labor Review 120, no. 3 (March 1997): 24–25; Nick Cafarado, "Q&A Everything You Wanted to Know about Baseball's Impending Strike but were Afraid to Ask," Boston Globe, August 9, 1994; Mark Maske, “At All-Star Break, No Relief for Baseball,” Washington Post, July 11, 1995; Murray Chass, “On Baseball,” New York Times, August 2, 1994; Ross Newhan, “The Players’ Donald Fehr and the Owners’ Richard Ravitch Have Mastered the South Bite,” Los Angeles Times, August 14, 1994; Tom Fitzpatrick, “The Baseball Strike: As Boring as it is Stupid,” Phoenix New Times, August 18, 1994; Thom Loverro, "The Baseball Strike: Close to the Action," Columbia Journalism Review 33, no. 6 (March 1995): 12.

4. Federal Baseball Club v. National League, 259 U.S. 200, 208-09 (1922); “Baseball and the Supreme Court,” Society of American Baseball Research Century Committee, accessed August 28, 2024, https://sabr.org/supreme-court/antitrust; Samuel Alito, “The Origin of the Baseball Antitrust Exemption,” Journal of Supreme Court History 34, no. 2 (July 2009): 183–95; Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc., 346 U.S. 356, 356–57 (1953); “Part 2: Baseball and the Antitrust Laws: The Unique Antitrust Status of Baseball,” in Neil B. Cohen, Paul Finkelman, and Spencer Weber Waller, eds., Baseball and the American Legal Mind (New York: Garland Pub., 1995), 75–160. For more on the antitrust exemption within the broader sporting landscape, see David George Surdam, The Big Leagues Go to Washington (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015).

5. Surdam, Big Leagues, 42–51; Examples of hearings include: Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subjecting Professional Baseball to Antitrust Laws: Hearings on S.J. Res. 133 to Make the Antitrust Laws Applicable to Professional Baseball Clubs Affiliated with the Alcoholic Beverage Industry, 83rd Cong., 2nd sess., March 18, April 8, May 25, 1954; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Professional Sports Antitrust Immunity: Hearings on S. 2784 and S. 2821, 97th Cong., 2nd sess., August 16, September 16, 20, 29, 1982; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Professional Sports Antitrust Immunity: Hearings on S. 172, S. 259, and S. 298, S.Hrg. 99-496, 99th Cong., 1st sess., February 6, March 6, June 12, 1985; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies and Business Rights on the Movement of Sports Programming onto Cable Television, S. Hrg. 101-1209, 101st Cong., 1st sess., November 14, 1989. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Baseball’s Antitrust Immunity: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies, and Business Rights on the Validity of Major League Baseball’s Exemption from the Antitrust Laws, S. Hrg. 102-1094, 102nd Cong. 2nd sess., Dec. 10, 1992.

6. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, S. Hrg. 102-1094, 2, 56, 330; L. Elaine Halchin, Justin Murray, Jon O. Shimabukuro, and Kathleen Ann Ruane, “Congressional Responses to Selected Work Stoppages in Professional Sports,” Congressional Research Service (CRS) R41060, updated January 15, 2013, 1.

7. Professional Baseball Antitrust Reform Act of 1993, S.500, 103rd Congress, 1st sess., 1993; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Professional Baseball Teams and the Antitrust Laws: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies, and Business Rights on S. 500, S.Hrg. 103-1054, Mar. 21, 1994, 1-4; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Legislative and Executive Calendar, Final Edition, S. Prt. 103-113, 103rd Congress, 18; Dave Kaplan, “Bill to Avert Baseball Strike Thrown Out by Senate Panel,” Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report, Vol. 52, No. 5, June 25, 1994, 1700; Tom Korologos to Senator Moynihan, 21 Sep. 1994, Folder 12, Box 574, Daniel P. Moynihan papers, 1765-2003, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

8. Halchin, et al, CRS Report, 29.

9. “Owners Look to Next Year,” Deseret News, Oct. 1, 1994, accessed August 28, 2024, https://www.deseret.com/1994/10/1/19133899/owners-look-to-next-year/; Congressional Record, 103rd Cong. 2nd sess., August 17, 1994, 22815 (statement of Sen. DeConcini); September 13, 1994, 24495 (statement of Sen. Howard Metzenbaum).

10. Congressional Record, 103rd Cong., 2nd sess., September 30, 1994, 26974–5 (statement of Sen. Durenberger), 26996–7 (statement of Sen. Wofford); August 3, 1994, 19394 (statement of Sen. Specter).

11. S.Amdt. 2601 to H.R.4649, Congressional Record, 103rd Cong., 2nd sess., September 30, 1994, 26977–91; “Nebraska Senator Nixes Vote,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 14, 1994; Staudohar, “Baseball Strike,” 25; Christopher J. Fisher, “The 1994-95 Baseball Strike,” Seton Hall Journal of Sports Law 6 (1996): 379–81; House Committee on the Judiciary, Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption (Part 2): Hearing before the House Subcommittee on Economic and Commercial Law, 103rd Cong., 2nd sess., September 2, 1994.

12. Staudohar, “Baseball Strike,” 26; National Pastime Preservation Act of 1995, S.15, 104th Cong., 1st sess., 1995; John Helyar and David Rogers, "Congress Resists Taking a Swing in Baseball Strike," Wall Street Journal, February 9, 1995.

13. Helyar and Rogers, "Congress Resists Taking a Swing,"; Major League Baseball Restoration Act, S.376, 104th Cong., 1st sess., 1995; Congressional Record, 104th Cong., 1st sess., February 9, 1995, 4258 (statement of Sen. Kennedy).

14. Major League Baseball Antitrust Reform Act of 1995, S.416, 104th Cong. 1st sess., 1995; Professional Baseball Antitrust Reform Act of 1995, S.415, 104th Cong., 1st sess., 1995; Fehr to Hatch, 10 February 1995, Folder 12, Box 574, Daniel P. Moynihan papers, 1765-2003, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Congressional Record, 104th Cong., 1st sess., February 14, 1995, 4823 (statement of Sen. Leahy); Senate Committee on the Judiciary, The Court-Imposed Major League Baseball Antitrust Exemption, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Business Rights and Competition on S.415 and S.416, S.Hrg. 104-682, February 15, 1995, 3, 6, 68–71.

15. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Report to Accompany S.627, Major League Baseball Reform Act of 1995, S.Rpt. 104-231, 104th Cong., 2nd sess., February 6, 1996; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, S. Hrg. 104-682 (1995), 7, 17, 87.

16. Major League Baseball Antitrust Reform Act, S.627, 104th Congress, 1st sess., 1995; “NLRB Votes to Seek an Injunction Against Owners,” Roanoke Times, March 27, 1995.

17. Silverman v. MLB Player Relations Comm., Inc. 880 F. Supp. 246, 261 (SDNY 1995); “Sixtieth Annual Report of the National Labor Relations Board,” National Labor Relations Board (1995), 96–7.

18. Curt Flood Act of 1998, S.53, 105th Cong., 1st sess., 1997.

19. Senator Patrick Leahy, statements on S.53, the Curt Flood Act, 1997–1998, Box 329-05-0073_10, Folder 05, Senator Patrick J. Leahy Papers, University of Vermont.

20. “Likely votes on bill supported by owners & players,” undated (ca. 1997), Senator Leahy and Senator Hatch, 28 February 1997, Fehr to Hatch, 25 July 1997, in Records of the U.S. Senate, 105th Congress, Committee on the Judiciary, Republican Legislative Files, Box 2, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Curt Flood Act of 1998, S.53, 105th Cong., 1st sess., 1997. For more on the impact of the Curt Flood Act, see Janice Rubin, “’Curt Flood Act of 1998’: Application of Federal Antitrust Laws to MLB Players,” Congressional Research Service (CRS) 98-820A, April 12, 2004; Edmund P. Edmonds, “The Curt Flood Act of 1998: A Hollow Gesture After All These Years?” Marquette Sports Law Review 9, No. 2 (Spring 1999): 315–46; and William Basil Tsimpris, “A Question of (Anti)trust: Flood v. Kuhn and the Viability of Major League Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption,” Richmond Journal of Law and the Public Interest (Summer 2004): 69–86; Congressional Record, 105th Cong., 2nd sess., July 30, 1998, 18176.

21. Congressional Record, 105th Cong., 2nd sess., July 30, 1998, 18176.

|

| 202112 03Beer by Christmas

December 03, 2021

The Christmas season often brings a sense of joyous anticipation as people celebrate the holiday, enjoy family gatherings, and eagerly await the opening of gifts. Would that special “something” be under the tree? In 1932 that “something” on many people’s wish list was beer.

The Christmas season often brings a sense of joyous anticipation as people celebrate the holiday, enjoy family gatherings, and eagerly await the opening of gifts. Would that special “something” be under the tree? In 1932 that “something” on many people’s wish list was beer.

The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in December 1917 and ratified by the states in January 1919, banned the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” To enforce the amendment, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act (named for its sponsor, Representative Andrew Volstead of Minnesota), in October 1919. Passed over a veto by President Woodrow Wilson, the Volstead Act defined an “intoxicating beverage” as anything that contained more than .5 percent alcohol. While much of the campaign against alcohol in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had focused on hard liquor, the act’s strict definition also outlawed beer and wine.1

After a decade of Prohibition and the challenges of enforcement—even in the halls of Congress—American politicians in the 1920s split between the “drys,” who wanted to maintain Prohibition, and the “wets,” who wanted it repealed. Both political parties were internally divided over the issue and for more than a decade refrained from adopting a national stance on the question of alcohol. In 1932, however, with the nation suffering through the Great Depression, the Democrats adopted a party platform that supported repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment and modification of the Volstead Act to allow for the manufacture of beer. The Republicans stopped short of endorsing repeal that year—their party platform stated the issue “was not a partisan political question”—but did support altering the amendment to allow states to decide the issue for themselves.2

With Franklin Roosevelt’s victory in the 1932 presidential election and Democratic majorities elected to the House and Senate, many believed that the end of the Prohibition Era was imminent. The election had been largely a referendum on economic issues, but popular majorities throughout the country had expressed support for legalizing alcohol again. In the November election, nine states voted to repeal their Prohibition statutes, and two others approved referenda supporting national repeal. Elected officials, including Louisiana senator Huey Long, began to state optimistically that Congress might deliver “beer by Christmas.” Throughout the country, beer producers, pubs, and taverns quietly made preparations in anticipation of serving beer by December 25.3

As Congress returned for a lame-duck session in December, which would last until March 4, 1933, the “wets” arrived in Washington ready to act. Speaker of the House John Nance Garner, soon to be Vice President Garner, made repeal of the Prohibition amendment the first order of business, but on December 5 Garner’s resolution fell six votes short of the necessary two-thirds majority. The “drys” had won that round, but the “wets” did not concede defeat. “Congress will legalize some sort of beer before Christmas,” Garner announced.4

House Democrats had already held meetings in November before the opening of the session, including with President-elect Roosevelt, and scheduled committee hearings for December 7 to consider a beer bill. Representative James Collier, chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, drafted a bill to legalize beer containing less than 2.75 percent alcohol, which he deemed “non-intoxicating.” Collier’s bill also provided for taxation of beer sales, which allowed supporters to emphasize that legalization would provide badly needed revenue to the federal government in the face of growing budget deficits. Beer producers urged the House to increase the allowable alcohol content to 3.2 percent and promised that they could employ 300,000 people and provide the government with $400 million in revenue over the next year.5

Despite a sense of urgency, the House committee did not report the bill until December 15, and another week passed before the House passed the bill on the 22nd. The prospect of “beer by Christmas” was now in the hands of the Senate. Could the Senate act quickly enough to make the Christmas deadline?6

On December 23, the Senate referred the Collier bill to the Judiciary Committee. Since it included a beer tax, the bill also went to the Finance Committee. With time running out, Republican senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut—who had just lost his re-election campaign and was now a lame-duck senator—attempted to bypass the committees and get quick action. Bingham had introduced his own beer bill at the start of the previous session of Congress. The Committee on Manufactures had considered his bill but reported it to the full Senate with the recommendation that it not pass. Despite the adverse report, the bill was still available on the Senate calendar. Believing that the political situation had changed, Bingham moved to call up his bill. He intended to amend it by substituting the bulk of the Collier bill for his, predicting the amended bill would promptly pass the Senate.7

When Bingham made his motion to proceed to his bill, however, Democratic Leader Joseph Robinson of Arkansas—soon to be majority leader—applied the brakes. Would any beer, even 3.2 percent beer, be constitutional under the Eighteenth Amendment, Robinson pondered? He insisted that the decision required more careful attention and should not be made with “undue haste.” As the popularity of repeal grew nationwide and Democrats prepared to take the majority on March 4, partisan gamesmanship was also at play. Robinson charged the Republican Bingham of attempting to “embarrass” and upstage the Democrats. As one reporter wrote, “The Democrats let it be known that they had no intention of letting a Republican lame duck steal both the show and the beer bill.” Consequently, Bingham watched his motion fail by a vote of 23–48. Frustrated, he complained that America wouldn’t see beer even by Valentine’s Day.8

Beer would not flow by Christmas or even by the end of the 72nd Congress, but in February of 1933 both houses of Congress approved a constitutional amendment to repeal Prohibition. While the country awaited ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment (which came in December 1933), the House and Senate convened the 73rd Congress on March 4 ready to act. On March 22, 1933, Congress passed the bill to legalize beer with an alcohol content of 3.2 percent or less. Within an hour, the bill was on President Roosevelt’s desk. Always in tune with public opinion, Roosevelt signed it into law and then reportedly remarked: “I think this would be a good time for a beer.”9

Notes

1. Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (New York: Scribner, 2010), 96–114.

2. Lisa McGirr, The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015), 157–88, 238–39.

3. “Beer by Christmas Seen by Huey Long,” Washington Evening Star, October 29, 1932, 3; “Nine States Voted Repeal of Dry Laws,” Wall Street Journal, November 15, 1932, 4.

4. “Beer Up Next,” Chicago Tribune, December 6, 1932, 1.

5. “Hearing on Beer to Start Dec 7,” Boston Globe, November 24, 1932, 15; “Beer for Revenue,” New York Times, November 25, 1932, 14; “Drys Forming Lines for Repeal Battle,” New York Times, November 28, 1932, 1; “Beer Hearing Begun, 3.2 percent Urged,” New York Times, December 8, 1932, 1.

6. “Beer Approved by Committee,” New York Times, December 16, 1932, 1.

7. A bill to amend the National Prohibition Act, as amended and supplemented, in respect to the definition of intoxicating liquor, S. 436, 72nd Cong., 1st sess., December 9, 1931; Senate Committee on Manufactures, Amendment of the Prohibition Act, S. Rpt. 72-635, 72nd Cong., 1st sess., May 3, 1932; “Bingham to Ask Vote in Senate on Beer Today,” Washington Post, December 23, 1932, 1.

8. Congressional Record, 72nd Cong., 2nd sess., December 23, 1932, 956–58; “Beer by Christmas Defeated as Senate Demands More Time,” New York Times, December 24, 1932, 1; “Beer Loses,” Chicago Tribune, December 24, 1932, 1.

9. “Beer Back After 13 Years,” Chicago Tribune, March 23, 1933, 1; “Roosevelt Signs Beer Bill,” Hartford Courant, March 23, 1933, 1; “Bill Signed; Capital Gets Beer Tonight,” Washington Post, April 6, 1933, 1.

|