The artist Seth Eastman was reportedly putting the finishing touches on his painting West Point, New York, when he died suddenly of a stroke in his Washington, DC, studio on August 31, 1875. This canvas was the last of a series of 17 paintings depicting mainly U.S. military forts that the artist created for Congress between 1870 and 1875. The paintings have been a fixture in the Capitol for most of their history. After their acquisition in 1875, they initially hung in spaces occupied by the House Committee on Military Affairs and later in the Cannon House Office Building. By early 1940, they had returned to the Capitol for public display in the first-floor west corridor. Eight of the paintings hang on the Senate side of the corridor and nine on the House side. Since the establishment of the Senate Commission on Art in 1968, the eight fort paintings in the Senate wing have been cared for as part of the U.S. Senate Collection. The 150th anniversary of the completion of these paintings provides a timely opportunity to revisit how Eastman’s military and artistic background informed his receipt of the commission and his approach to depicting these subjects.1

“Paintings from His Own Designs”

The genesis of the series was a joint resolution introduced by Representative Robert C. Schenck of Ohio on March 26, 1867 (H.J. Res. 42). Schenck, the chairmen of the Committee on Ways and Means, proposed “authorizing the employment of Brevet Brigadier General Seth Eastman of the United States Army, now on the retired list, to duty…to execut[e] under the supervision of the Architect of the Capitol…paintings from his own designs for the decorations of the rooms of the Committee on Indian Affairs and on Military Affairs of the Senate and House of Representatives, and other parts of the Capitol.” Though the House approved the resolution, Senator Henry Wilson, chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs and the Militia, “moved its indefinite postponement,” which was agreed to on March 2, 1868. With the joint resolution tabled in the Senate, the Architect of the Capitol Edward Clark moved forward separately to have the artist make paintings first for the House Committee on Indian Affairs (a series of nine paintings completed in 1869) and then for the Committee on Military Affairs (1870–1875).2

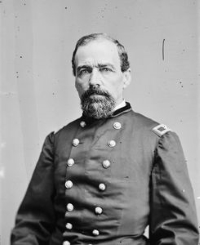

As both a military officer and an artist, Eastman was well positioned to create artwork for the federal government. Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, he was the eldest of 13 children. Though his father hoped he would attend Bowdoin College, young Eastman had an interest in the military and enrolled at West Point in July 1824 at the age of 16 years old. Though Eastman was not generally a strong student—he took five years to graduate instead of the usual four—he excelled in draftsmanship. In the two-year art class at the military academy, he learned skills relevant to military work, including figure drawing, landscape drawing, and topographical drawing.3

Eastman’s approach to depicting forts, with its focus on architectural details and the structures’ relationship to the landscape, evidences this training. An October 1829 pencil sketch that Eastman made at Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien, Michigan Territory (present-day Wisconsin), shows many of the hallmarks of his series of fort paintings executed more than four decades later. Eastman’s first assignment after graduating from West Point was to help rebuild Fort Crawford, where then-Colonel Zachary Taylor was overseeing the construction of a new stone fort to replace the original timber one. Eastman’s drawing illustrates the first Fort Crawford from a slightly elevated viewpoint, with the fort located in the middle ground and boats on the Mississippi River visible in the foreground. The overall mood of the work is calm and serene with placid water and cloudless skies. Though Eastman did not illustrate Fort Crawford in his 1870s fort paintings, the artistic strategies employed in this early drawing of a fort anticipate, in overall effect, many of the later paintings. Fort Knox, Maine, for example, similarly illustrates the fort from a nearly identical perspective, with the composition divided horizontally into sky, land, and water. Small civilian figures in boats in the foreground of both works contribute to the overall quotidian impressions of the scenes.

“Gallant American Officer [with] Taste and Artistic Ability”

Members of Congress who advocated for Eastman to receive the commission viewed him as a skilled artist who could provide quality artwork for the Capitol at an affordable price. Because the federal government already employed him as a member of the military, Eastman could be hired to create the artwork as part of his military duties and, therefore, at little additional cost. Representative Schenck, in his proposed joint resolution, emphasized this point, clarifying that “no additional compensation for such service is to be paid to said Eastman beyond his pay, allowances and emoluments” as a brevet brigadier general in the United States Army. Members of the Senate had previously championed Eastman as a potential cost-effective source of imagery for the Capitol. During a discussion on the Senate floor on June 10, 1852, about whether Congress should purchase a collection of paintings of Native American subjects by artist George Catlin, Senator Solon Borland of Arkansas spoke in favor of commissioning Eastman to create artwork instead. The artist was, at the time, illustrating Native American subjects for Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s six-part publication, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (published 1851–1857), authorized by an act of Congress and produced by the Office of Indian Affairs. Because of this, Borland argued that the quality of Eastman’s artwork was already evident. In addition, he noted, Eastman was willing to do the work for his regular military pay, a sum far less than Catlin’s fee.4

Besides the attractive price offered by Eastman, the artist was also an appealing choice for many members of Congress because of his nationality as a native-born U.S. citizen. The recent and extensive efforts to decorate the new Capitol extensions during the 1850s and 1860s had prompted heated debates within Congress about the extent to which Engineer of the Capitol Montgomery C. Meigs had awarded contracts to foreign-born artists, especially Constantino Brumidi. Brumidi created the elaborate fresco decorations found throughout much of the Senate wing and the Capitol Rotunda between 1855 and 1880. Today these murals are considered among the most iconic and beloved features of the Capitol’s interior, but they were once a source of outrage for many American-born artists who wished that they, too, could benefit from government patronage as well as for members of Congress who believed federal funds should support American artists instead. (Brumidi became a naturalized citizen in 1857, but that did little to quell the criticism.) The Washington Art Association, an organization of which Eastman was an active member, worked during this period to win broader congressional support to reform the process of awarding government arts commissions. Eastman served as a director of the Washington Art Association in 1858 and 1860 and exhibited paintings at the organization’s annual exhibition between these years. Sculptor Horatio Stone, who served as the president of the Washington Art Association, argued specifically that artists—not engineers (a direct attack on Meigs)—should determine who gets the commissions and approves the designs. Furthermore, Stone emphasized the nationalism behind the group’s efforts, declaring, “The time has come for a more expanded exertion of the genius of this nation upon works of national art.”5

In this context, Eastman’s status as a native-born U.S. citizen and his military service made him a politically appealing choice. Representative Schenck pointed to these facts in 1867, when he proposed that Congress hire Eastman, stating, “We have been paying for decorations, some displaying good taste and others of a tawdry character, a great deal of money to Italian artists and others, while we have American talent much more competent for the work.” Singling out Eastman specifically as possessing “native talent,” Schenck added, “I think under the circumstances a gallant American officer, who has taste and artistic ability, should be permitted to be assigned to this duty.” Ultimately, Schenck prevailed, and, by 1870, Eastman was at work on the series for the Committee of Military Affairs.6

Forts from All Regions

It is not certain why Eastman portrayed the 15 particular locations depicted in the series, and whether the sites were suggested by the artist, the committee, or a combination of both. The paintings picture locations in various states, including Maine (Fort Knox and Forts Scammel and Gorges), Connecticut (Fort Trumbull), New York (West Point, Fort Lafayette, and Forts Tompkins and Wadsworth), Pennsylvania (Fort Mifflin), Delaware (Fort Delaware), South Carolina (three different paintings of Fort Sumter), Florida (Fort Taylor and Fort Jefferson), Michigan (Fort Mackinac), Minnesota (Fort Snelling), North Dakota Territory (Fort Rice), and New Mexico Territory (Fort Defiance). It was unlikely that Eastman, who was advanced in years and in poor health at the time of the commission, visited the forts during the five-year period he painted them. However, he had been stationed at or visited at least three of them earlier in his military career. Perhaps his familiarity with West Point (where he lived in 1824–1829 and 1833–1840), Fort Snelling (where he was stationed in 1830–1831 and 1841–1848), and Fort Mifflin (where he was in command in 1864–1865) helped determine their inclusion in the series. When creating his later oil-on-canvas series, the artist drew from an extensive archive of drawings and watercolors that he had made of these locations years earlier. His role as a Mustering and Dispersing Officer for his home state of Maine and for New Hampshire at the beginning of the Civil War (1861–1863) may have also brought him into contact with Fort Knox (which garrisoned troops during the war) and Forts Gorges and Scammel. Eastman likely had access to plans, elevations, and even photographs of the forts in the series that he probably did not visit in person. Trained in topographical draftsmanship, he would have had the skills necessary to translate these resources into his own compositions.7

Eastman had also portrayed some locations, like Fort Defiance, in prior publications. Eastman’s painting Fort Defiance, New Mexico (now Arizona) is very similar to the illustration he made for Schoolcraft’s publication. Established as a U.S. military fort in 1851, the site was largely abandoned in 1861 but was reestablished in 1868 as an Indian agency rather than an active fort. Eastman’s illustration published in Schoolcraft’s text indicates that it was based on a sketch provided by Lt. Col. Joseph H. Eaton, who was stationed at the fort for “frontier duty” in 1852–1853. Eaton attended West Point from 1831 to 1835, and it is probable that he would have studied with Eastman, who joined the faculty there as a drawing instructor in 1833. Eastman must have used Eaton’s sketch as the basis for the various preparatory studies he created while working to illustrate Schoolcraft’s publication, including a drawing and watercolor that are both in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.8

Architectural Tranquility

Though several of the locations played a role in the recent Civil War, Eastman’s paintings show little evidence of this history. Instead, the artist took a deliberately restrained pictorial approach to depicting the forts. His tranquil representation of Fort Delaware, for example, reveals nothing of the site’s history as an infamous prisoner of war camp for captured Confederate soldiers. Completed in 1859, Fort Delaware was the United States’ largest fort on the eve of the Civil War. In 1862 it became a prison, and by the following year most of the Confederate soldiers captured at the Battle of Gettysburg were held in barracks located just northwest of the fort. By the end of the war, more than 30,000 people had been imprisoned there. Due to overcrowding, conditions were notoriously bad, and diseases spread rampantly; more than two thousand prisoners died in custody. Though Eastman was never stationed at Fort Delaware, he had direct knowledge of such Civil War prisons. In 1864 he was ordered to prepare and command what would become known as one of the most brutal Civil War prisons, Elmira in New York, which, like Fort Delaware, was plagued by poor sanitation and insufficient supplies. Eastman’s painting of Fort Delaware shows the low block of the massive fort as seen from the east, nestled into a serene landscape and softly illuminated by the morning light.9

This restrained pictorial approach was a conscious decision. On June 16, 1870, Representative John A. Logan of Illinois, chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs, wrote a letter to Architect of the Capitol Edward Clark requesting that Eastman make paintings “for the decoration of the Military Committee Room of the House of Representatives, in the same manner as the room for the Committee on Indian Affairs.” Logan and Eastman met to discuss the commission, and the two agreed that the canvases should depict the architecture of the forts and a view of West Point, rather than representing active battle scenes.10

This choice is a marked contrast from another mid-19th century commission for the Capitol that depicts a fortress, The Battle of Chapultepec (Storming of Chapultepec), which was painted in 1857–1858 by artist James Walker and delivered to the Capitol in 1862. The painting, commissioned as part of Meigs’s program to decorate the rooms of the newly constructed Capitol extensions, pictures the consultation between General John Anthony Quitman and his officers during the storming of the Mexican fortress at Chapultepec on September 13, 1847. Chapultepec Castle appears high on a hill under a dramatic sky, with dynamic crowds of American soldiers readying for battle in the foreground. After reviewing Walker’s studies for the painting, Meigs described them in his journal as “as full of life and knowledge as any battle pieces I have ever seen.” Meigs’s initial notes about the painting reveal he intended for it to hang in the meeting room of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. However, soon thereafter, records indicate that the painting was promised for the House Committee on Military Affairs. Its completion was much delayed due to uncertainties around funding (driven, in part, by the debates, discussed above, about how federal art commissions should be awarded); after its arrival at the Capitol in 1862, it was installed in the west grand staircase of the Senate wing where it hung for more than a century. Three years later, in 1865, the Joint Committee on the Library commissioned artist William Henry Powell to paint another monumental battle scene, Battle of Lake Erie, which was installed in the east grand staircase of the Senate wing upon its completion in 1873. These two monumental battle scenes, with their emphasis on narrative and drama, offered an alternative artistic vision for celebrating American military achievement.11

Today, the Senate wing of the Capitol features a wide variety of fine art in the public staircases and corridors, including Eastman's fort series, Brumidi's murals, and Powell's naval battle scene. The historical nuances of debates about which artists should decorate the Capitol extensions, who should award the commissions, and how the nation’s military might should be represented are no longer obvious. The anniversary of the completion of Eastman’s fort paintings prompts a deeper look into the paintings’ origins and their relationship to other works of art commissioned for the Capitol around the same time.

Notes

1. Patricia Condon Johnston, “Seth Eastman’s West,” American History (August 19, 1996), HistoryNet.com, accessed July 14, 2025, https://www.historynet.com/seth-eastmans-west-october-96-american-history-feature/; William Kloss and Diane K. Skvarla, “Principal Fortifications of the United States,” in United States Senate Catalogue of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2002), 128–29.

2. Congressional Globe, 40th Cong., 1st sess., March 26, 1867, 361–62; Congressional Globe, 40th Cong., 2nd sess., March 2, 1868, 1567; Felicia Wivchar, “The House Indian Affairs Commission—Seth Eastman’s American Indian Paintings in Context,” Federal History 2 (2010): 19; letter from Edward Clark to Seth Eastman, June 16, 1870, Office of Senate Curator files.

7. Bvt. Maj.-Gen. George W. Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., from Its Establishment, in 1802, to 1890, with the Early History of the United States Military Academy, 3rd ed., vol. 1 (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company; Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1891), 435–436; Kloss and Skvarla, “Principal Fortifications of the United States,” 129.

8. Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1854), Part 4, 210, Plate 30; Kloss and Skvarla, “Principal Fortifications of the United States,” 130; Cullum, Biographical Register, 619; "Fort Defiance I," Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accessed July 14, 2025, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/158320/fort-defiance-i; "Fort Defiance II," Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accessed July 14, 2025, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/4502/fort-defiance-ii?ctx=2df7c5ae-93b3-4784-b296-42686a02e570&idx=0.

9. Kloss and Skvarla, “Principal Fortifications of the United States,” 132; “Confederate Burials in the National Cemetery,” U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/signs/Finns-Point-National-Cemetery-NJ-Confederate-Burials-Interpretive-Sign.pdf.