Congress Week—celebrated each April to commemorate the week in 1789 when the House of Representatives and the Senate first achieved a quorum—was established to promote the study of Congress and to encourage a wider appreciation of the vital role of the legislative branch in our representative democracy. This year, in recognition of the centennial of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, we celebrate Congress Week by exploring how Senate historians used congressional collections to develop the online feature, “The Senate and Women’s Fight for the Vote.”

Formally proposed in the Senate for the first time in 1878, the Nineteenth Amendment was finally approved by the Senate 41 years later, on June 4, 1919. Ratified the following year, the amendment extended to women the right to vote. To tell the story of the suffragists’ protracted campaign to win that right, Senate historians delved into a variety of primary sources, including petitions, congressional hearings and reports, and the personal papers of U.S. senators.

Records of Congress

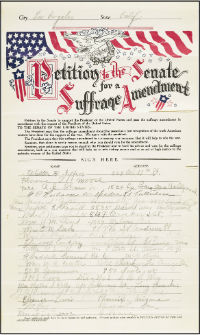

The Center for Legislative Archives at the National Archives (where congressional records are stored) houses a vast collection of woman suffrage records. The bulk of these records consists of petitions created by tens of thousands of suffragists who exercised their First Amendment right. Their petitions come in all shapes and sizes. Some of them are as brief as a telegram, while others include hundreds of signatures pasted or stitched together and rolled up in large bundles. Senate historians combed through scores of petitions to understand not only the suffragists and their demands but also those who opposed woman suffrage.

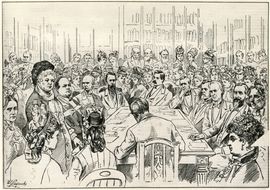

Senate historians also consulted speeches printed in the Congressional Record and committee hearing transcripts and reports to understand senators’ evolving attitudes toward woman suffrage. When California senator Aaron Sargent introduced the woman suffrage amendment to the Constitution in 1878, the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections agreed to allow women to testify in support of the amendment. After hearing from witnesses, including suffrage pioneer Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Reverend Olympia Brown, the committee’s majority remained unconvinced and recommended that Sargent’s proposal be “indefinitely postponed.” A few senators voiced their dissent. “The American people must extend the right of Suffrage to Woman or abandon the idea that Suffrage is a birthright,” concluded Senators George Hoar (R-MA), John H. Mitchell (R-OR), and Angus Cameron (R-WI).

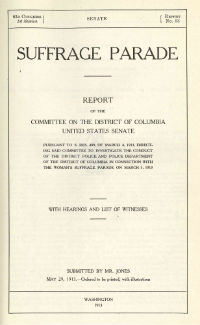

In 1913, following a historic suffrage parade in the nation’s capital, a Senate subcommittee investigated the chaotic and hostile conditions endured by suffragists along the parade route. The voluminous testimony and photographs published in these hearing volumes provide compelling evidence of lewd comments, physical assaults, and intimidation, as well as the volatility of the massive crowds of people that converged along the parade route. In the wake of these dramatic hearings, the committee concluded that the police had acted with “apparent indifference and in this way encouraged the crowd to press in upon the parade.”

Senators’ Papers

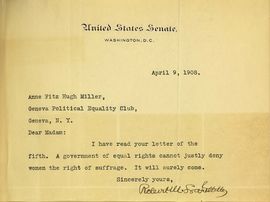

To delve deeper into this rich and engaging story, the historians also ventured outside the Senate’s official holdings at the National Archives to explore the personal papers of individual senators and suffragists, as well as the records of suffrage organizations housed in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Correspondence between senators and their constituents often revealed the motivation behind a senator’s decision to support or oppose the amendment.

Idaho senator William Borah, for example, who opposed the national suffrage amendment, insisting it was an issue best left to the states, justified his opposition to the amendment in letters to concerned constituents. “I am aware . . . [my position] will lead to much criticism among friends at home,” he wrote. “I would rather give up the office,” he continued, “[than] cast a vote . . . I do not believe in.” Wisconsin senator Robert La Follette succinctly explained his support for the proposal in a letter to Anne Fitzhugh Miller: “A government of equal rights cannot justly deny women the right of suffrage. It will surely come.” Like the petitions in the National Archives, such letters offer a palpable sense of the engagement of citizens with their senators.

Organizational Archives and Other Primary Sources

Senate historians reviewed archival materials housed at the National Woman’s Party (NWP) at the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, including materials related to the organization’s complex lobbying operation and a political cartoon collection by artist Nina Allender. Many of Allender’s cartoons prominently featured the Senate.

A deep dive into the extensive photographic collection at the Library of Congress turned up a host of illuminating images to illustrate suffrage campaign activities at the Capitol and the Senate Office Building, as suffragists assembled to deliver their petitions and to demand the right to vote.

An exhaustive review of historical newspapers and periodicals revealed personal testimonials and editorials. Particularly informative was the series of articles written by suffragist Maud Younger and published in McCall’s magazine in 1919, just after congressional passage of the amendment. Entitled “Revelations of a Woman Lobbyist,” Younger’s intimate account provides an insider’s view of the extensive lobbying campaign suffragists waged to win House and Senate approval of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Primary sources such as photos, petitions, speeches, published hearings, correspondence, historical newspapers, and periodicals are all essential to the historian’s work. Our special feature, “The Senate and Women’s Fight for the Vote,” which drew upon all of those resources and more, demonstrates the value and importance of congressional archives. Without these records, the important role played by suffragists and their allies in the Senate’s long battle over the suffrage amendment would be lost or forgotten.