| 202508 29Fifty Years of Preserving and Promoting Senate History

August 29, 2025

In May 1974, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and political historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., wrote a letter to Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield supporting a proposal to establish a Senate Historical Office. “The creation of such an Office would be of benefit,” Schlesinger wrote, “not only to historians and concerned citizens but to the Senate itself.” The next year, with the bipartisan blessing of Mansfield and Republican leader Hugh Scott, the Senate Historical Office was established on September 1, 1975.

In May 1974, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and political historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., wrote a letter to Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield supporting a proposal to establish a Senate Historical Office. “The creation of such an Office would be of benefit,” Schlesinger wrote, “not only to historians and concerned citizens but to the Senate itself.” Schlesinger understood that the twin political crises of the 1970s—the Watergate scandal and the unpopular Vietnam War—had caused a growing number of Americans to lose faith in their institutions and to demand greater transparency from them. “If we are going to persuade the nation that Congress plays a role in the formation of national policy,” he wrote, “Congress will have to cooperate by providing the evidence for its contributions.” The next year, with the bipartisan blessing of Mansfield and Republican leader Hugh Scott, the Senate Historical Office was established on September 1, 1975.1

Tasked with overseeing the new office, Secretary of the Senate Francis Valeo articulated its mission. “Executive Branch departments and agencies have long had large historical offices and have long published or made public many of their important confidential papers,” Valeo explained in a letter to Senate appropriators justifying the creation of the new office. A Senate historical office would assist in the “organization of the Senate’s historic documentation,” serve as a “clearing house for public requests concerning historical subjects,” and “collect and preserve photographs depicting the history of the Senate.”2

Valeo hired Richard Baker to lead the new office. Baker brought a unique blend of skills and experience to the role. With degrees in history and library science, Baker had served as the Senate’s acting curator from 1969 to 1970 and then as vice president and director of research for the National Journal’s parent company. Former Washington Times staff photographer Arthur Scott filled the position of photo historian. Baker soon hired Leslie Prosterman as a research assistant and Donald Ritchie as a second historian.

Historians and newspapers heralded the office’s creation. “On behalf of the [American Historical] Association I want you to know how pleased we are that the Senate has established this new historical office,” wrote Mack Thompson, the organization’s executive director. “Much of the Senate’s business in the past was conducted in closed committee meetings,” noted Roll Call, leaving Senate records “locked away and forgotten,” resulting in the “history of significant public policy issues [being] written from the perspective of the Executive Branch where confidential records are generally declassified and published on a systematic basis.” The New York Times predicted that there would be much interest in the Senate’s “closed-door briefings on Pearl Harbor, the Cuban missile crisis, and the missile-gap controversy of the Eisenhower administration.” Generations of reporters, historians, and political scientists would come to rely upon the non-partisan expertise provided by Senate historians.3

One of the office’s most pressing early tasks was locating and arranging for the proper preservation of the Senate’s “forgotten” records. “Most senators in 1975 had given little thought to their papers,” recalled Baker in an oral history interview in 2010. Baker’s job was to persuade senators that selecting a repository for their papers was “prudent management practice … in the interest of public access.” There was much work to be done. Baker found humid attic and dank basement storerooms in the Russell Senate Office Building filled to overflowing with committee and member papers. A recent basement flood had destroyed 30 years of irreplaceable materials. Similarly, attic spaces, where temperatures soared in the summer and the prospect of a fire was not unthinkable, were ill-suited for safely preserving records. Racing the clock, Senate historians appraised collections and helped arrange for their long-term preservation. “Our major role is advisory,” Baker wrote during those early years. “We do not intend to build our own archives … [but to facilitate] the flow of archival materials to repositories where they will receive sufficient care and exposure.”4

The tidal wave election of November 1980 brought renewed urgency to Senate historians’ work. Eighteen departing senators had only a few months to vacate their offices. Some were leaving voluntarily, while others had been unexpectedly retired by their constituents. Historical Office staff scrambled to assist departing members—including Warren Magnuson of Washington State and Jacob Javits of New York, whose combined congressional service totaled 78 years—with moving their voluminous record collections to hastily designated repositories. Soon after that election, Baker hired Karen Paul as the Senate’s first archivist. Paul would devote the next 43 years of her career to advising senators, staff, and officers on the preservation and disposition of their records, developing archival policies and practices to ensure the preservation of Senate records for future generations, and building a community of professional Senate archivists.

Over the past five decades, the Senate Historical Office has built partnerships and institutional capacities to aid in the preservation of congressional records for the long term. Working with congressional leadership, the Historical Office helped to establish a separate division within the National Archives to serve as the official repository for congressional committee records in 1985—named the Center for Legislative Archives in 1988. In 1990 the Office co-founded the Advisory Committee on the Records of Congress to explore issues pertinent to congressional records management, and it co-created the Association of Centers for the Study of Congress in 2004, a nationwide consortium of congressional records repositories and research institutes. Today, Senate archivists continue to advance the Senate’s historical record by shaping how its documentation is preserved and accessed. They have developed and updated official records management policies and have pioneered digital preservation practices, creating workflows for archiving email, social media, and audiovisual records in line with national standards. Senate archivists also provide specialized staff training that equips members and support offices, as well as committees, to manage both paper and electronic records with confidence. The Historical Office also administers the Secretary of the Senate’s Preservation Partnership Grants that strengthen the capacity of repositories across the country to process and provide access to senators’ papers, broadening the range of materials available for research. This work safeguards the very documentation on which Senate history rests.

While preserved official records illuminate aspects of Senate history, they rarely tell the full story of an institution’s evolution. From the Historical Office’s earliest days, Senate historians have sought to document the social, cultural, and technological changes within the Senate with the Senate Oral History Project. Don Ritchie developed and led the project, with a mission to record and preserve the experiences of a diverse group of personalities—both staff and senators—who witnessed events firsthand and offer a unique perspective on Senate history. Interviews help to explain, for example, women’s evolving role in the Senate, and the impact of changing technology on the institution. There were no women senators serving in 1975, while 26 women serve in the 119th Congress. Only one senator’s office used a computer in 1975 to manage constituent services, while today, emails, the internet, and social media are ubiquitous Senate-wide. Collectively, these oral histories help to promote a fuller and richer understanding of the institution’s evolution and of its role in governing the nation.

The advent of the internet in the mid-1990s provided new opportunities to share Senate history with a broader range of audiences. When Betty Koed joined the team as assistant historian in 1998, she began populating the (then relatively) new Senate website with oral history transcripts and historical information. Today, the Historical Office has integrated a wealth of Senate history across Senate.gov, created a Senate Stories blog, and developed online exhibits including “The Civil War: The Senate’s Story,” “The Civil Rights Act of 1964,” “States in the Senate,” and “Women of the Senate.”

Since its founding, the Historical Office has developed and maintained a reputation among senators, staff, journalists, scholars, and the general public for providing fact-based, non-partisan information about the institution’s history. Its staff manage dozens of statistical lists and maintain information about senators and vice presidents in the online Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Historians lead custom tours for members and staff and deliver history “minutes”—brief Senate stories about a subject of their choosing—at the party conference luncheons and for the Senate spouses. They offer brown bag lunch talks, deliver committee and state legacy briefings, and host an annual Constitution Day event. Historical Office staff have provided background and research support for dozens of books on the Senate, as well as historic events such as inaugural ceremonies, three presidential impeachment trials, and the 1987 congressional session convened in Philadelphia to commemorate the bicentennial of the Great Compromise which paved the way for the signing of the U.S. Constitution.

In addition to these varied services, Senate historians have supported a number of projects for members and committees, including Senator Robert C. Byrd’s four-volume The Senate, 1789–1989; Senator Robert Dole’s Historical Almanac of the United States Senate; the executive sessions of the Committees on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (1953) and Foreign Relations (1947–1968); and Senator Mark Hatfield’s Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993. The Historical Office team has authored print publications including the United States Senate Election, Expulsion and Censure Cases, 1793–1990 (1995); 200 Notable Days: Senate Stories 1787–2002 (2006); Scenes: People, Places, and Events That Shaped the United States Senate (2022); and Pro Tem: Presidents Pro Tempore of the United States Senate (2024). The Office has helped to document party histories by editing the minutes of the Republican and Democratic Conferences and producing A History of the United States Senate Republican Policy Committee, 1947–1997. These publications have been illustrated, in part, with images drawn from the Historical Office’s rich photo collection.

During the past half-century, the Historical Office has adapted to meet the needs of an ever-evolving institution while continuing to provide the services first articulated by Secretary of the Senate Valeo in 1975. Today, its staff of 12 historians and archivists are dedicated to preserving and promoting Senate history for the next 50 years.

Notes

1. Letter from Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., to the Honorable Mike Mansfield, May 6, 1974, in Senate Historical Office files.

2. Senate Committee on Appropriations, Legislative Branch Appropriations for Fiscal Year 1976: Hearings on H.R. 6950, 94th Cong., 1st sess., April 21, 1975,1258.

3. Mack Thompson to Mr. Richard Baker, March 25, 1976, in Senate Historical Office files; “Senate Historian,” Roll Call, October 23, 1975; “Senate Office To Publish Declassified Documents,” New York Times, October 19, 1975.

4. "Richard A. Baker: Senate Historian, 1975–2009," Oral History Interviews, May 27, 2010, to September 22, 2010, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.; Richard A. Baker, “Managing Congressional Papers: A View of the Senate,” American Archivist 41, no. 3 (July 1978): 291–96.

|

| 202506 20From Paper to Pixels: The Transformation of Congressional Archives

June 20, 2025

The legacy of generations of U.S. senators—contained in letters, memos, photographs, handwritten notes—rests in climate-controlled stacks, preserved by acid-free folders for the enduring curiosity of researchers. But in recent decades, the nature of archives has changed. Where once the record lived in ink and envelope, it now resides in networks, clouds, and code. From the meticulously penned letters of Senator Albert Beveridge to the terabyte of digital data in Senator John McCain’s recent donation, the evolution of archival practice reveals both challenge and opportunity.

The legacy of generations of U.S. senators—contained in letters, memos, photographs, handwritten notes—rests in climate-controlled stacks, preserved by acid-free folders for the enduring curiosity of researchers. But in recent decades, the nature of archives has changed. Where once the record lived in ink and envelope, it now resides in networks, clouds, and code.

The transformation of congressional archives from paper to born-digital formats reflects more than a shift in technology. It marks a turning point in how our national memory is preserved and how these unique records are accessed by future generations. From the meticulously penned letters of Senator Albert Beveridge to the terabyte of digital data in Senator John McCain’s recent donation, the evolution of archival practice reveals both challenge and opportunity.

The Tangibility of Tradition: The Albert J. Beveridge Papers

Republican Albert J. Beveridge represented Indiana in the U.S. Senate from 1899 to 1911. Throughout his career he championed several progressive causes, including consumer food safety and a 1906 proposal to ban child labor, which eventually led to the passage of the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act of 1916. The bulk of his papers, housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., span more than 40 years of American thought and politics. These are records you can touch: crisp correspondence written in iron gall ink, typed speeches on onion-skin paper, and newspaper clippings folded with care. Comprising roughly 100,000 items, this collection reflects the conventions of its age—arranged into defined series and stored in more than 400 carefully arranged boxes on climate-controlled shelves.1

The challenges of preserving such a collection are tactile and environmental. Paper degrades. Ink fades. Heat and humidity hasten decay. Archivists face constant vigilance—controlling light exposure, monitoring temperature, and conserving fragile pages. Accessibility, too, presents challenges. With no digital surrogates and limited item-level description, researchers rely upon finding aids and box lists, rather than modern keyword searches and remote computer access.

Yet there is a poetry to these physical documents. The weight of history is felt quite literally in one’s hands. Senator Beveridge’s papers offer an intimate, almost sensory connection to the past—one that remains indispensable, even as archival strategies have evolved. The decision to place his papers in the Library of Congress ensured that accessibility to this connection would outlive the senator’s lifetime. Researchers who utilize Beveridge’s records can find drafts of speeches and articles, general correspondence, as well as records tracing the evolution of state and national politics.2

Bridging Eras: The Daniel Patrick Moynihan Papers

Senators’ commitment to provide public access to their congressional records carried into the digital age. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Democrat, represented New York from 1977 to 2001, a period during which he emerged as one of the Senate’s leading voices on social welfare policy, intelligence oversight, and government transparency. His career, like his papers, spanned textual and digital worlds. Housed in the Library of Congress, his 1.3 million-item collection includes not only the expected letters, memos, and photographs, but also 275 digital files—early artifacts of a changing technological landscape.3

These born-digital components, modest in number but rich in complexity, introduced new demands on archival work. Floppy disks and CD-ROMs offered neither durability nor standardization. Rapidly evolving file formats threatened obsolescence almost as quickly as they emerged. Some emails arrived as printed pages, others as saved text files, and archivists were left to piece together the whole, tracing context, connection, and chronology across media types.

Senator Moynihan’s archive is a study in contrast—a bridge between worlds. As technology evolved, so too did the demands on archival practice. For archivists, this collection offered an early test case in managing hybrid records, foreshadowing the complexity that would soon become the norm. For researchers, it remains a vivid portrait of an era when word processors began to replace typewriters and the archive started to slip beyond the page. That portrait exists today because Senator Moynihan understood the importance of preserving and making available all of his records.

Into the Digital Fold: The Joseph Lieberman Papers

The political career of Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut spanned 40 years, from his service in the state senate (1970–1980) to his terms as state attorney general (1983, 1986–1988), to his tenure as U.S. senator (1989–2013). By the time he retired in 2013, email was ubiquitous, documents lived on shared drives, and offices were moving quickly toward a paperless environment. His donation of his political collection to the Library of Congress included 1,500 boxes of physical material and an extensive volume of digital content—emails, early word processing files, staff memos, legislative drafts, digital photographs, and other electronic records—from his personal Senate office. These records document Lieberman’s legislative efforts to protect the environment, safeguard the nation through the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, secure access to healthcare, and advance civil rights, among other accomplishments.4

During Senator Lieberman’s tenure, his staff did what few had done before—they prepared their digital records for eventual deposit in an archive. Aware of the long-term importance of these records, his staff established policies to save documents, organize file folders, and capture day-to-day interactions and decision-making. By choosing to include these digital records in his collection, particularly internal communications and staff correspondence (then an uncommon practice), Senator Lieberman, a Democrat turned Independent, demonstrated a commitment to government accountability. “I have long been a proponent of open government and transparency,” Lieberman explained. “Because so much of our work is conducted electronically, it seemed logical for me to include my emails as part of my Senate archives.”5

Archivists, in turn, faced a daunting task: processing terabytes of files in a jumble of formats, many tied to proprietary platforms, some stored in legacy systems long since abandoned. Maintaining such a collection demands more than hardware. It requires fluency in digital archival standards and systems capable of safeguarding the integrity of digital records. Context must be preserved—not just the content of an email, but who sent it, who received it, and what thread it answered. Without this, digital records become hollow shells, stripped of meaning.

Digital collections raise complex questions for archivists—how to balance openness with privacy, manage large quantities of sensitive correspondence, and navigate issues of ownership, redaction, and access in a networked environment. As processing of his collection continues in preparation for public access, Senator Lieberman’s papers serve as an early test case for how digital legacies can be responsibly managed in an era of rapid technological change. His collection pushed the boundaries of traditional archival practice.

Archives in the Cloud: The John S. McCain Papers

While the Lieberman Papers reflect a growing awareness of the importance of digital stewardship, the Senator John S. McCain Papers at Arizona State University (ASU) offer a detailed case study of the challenges and solutions that come with managing a born-digital archive that encompasses millions of files.

Republican John S. McCain III represented Arizona in the House of Representatives from 1983 to 1987 and in the U.S. Senate from 1987 until his death in 2018. McCain’s legislative initiatives included campaign finance reform, veterans’ affairs, national security and defense, immigration, and international human rights. ASU first acquired Senator McCain's House papers in the late 1990s. The McCain family significantly expanded the collection by donating the senator's extensive Senate and campaign records to ASU in 2019. This donation included more than 1,900 linear feet of paper and over 1 terabyte of digital files—totaling more than 3.9 million individual items and thousands of unique file types.6

Managing a modern congressional collection of significant size and complexity requires thoughtful investment in space, technology, and personnel. Successful stewardship depends on assembling a team with expertise in both traditional archival practices and digital preservation strategies. Institutions must often acquire specialized equipment, secure storage solutions, and robust computing infrastructure to support access, processing, and long-term care. Archivists may apply methods such as selective sampling and digital forensics to assess, stabilize, and prepare the collection for future use while maintaining the authenticity and integrity of the records.

The McCain Papers and the plan for their eventual availability to researchers and the public demonstrate how modern congressional archives are shaped not just by what is donated but also by how they are managed. Senator McCain’s records reflect more than a senator’s career; they show how a legacy of public service now depends on the effective preservation and accessibility of digital information. Preserving born-digital records at this scale requires institutional readiness, including adequate infrastructure, technical skills, strategic planning, and meaningful engagement with the public through outreach, collaboration, and transparency. For repositories facing similar challenges, the McCain collection provides a model for preserving and providing access to the complex digital record of a senator’s public service.

The Archival Pivot: Challenges and Continuities Toward Legacy and Stewardship

These four collections reflect a clear evolution from the linear logic of paper files to the dynamic sprawl of digital ecosystems. Each stage has demanded its own kind of care. For paper, that care means controlled humidity, acid-free folders, and meticulous arrangement. For hybrid collections, it means recovering obsolete formats, aligning analog and digital content, and building new description practices. For digital archives, it means maintaining file integrity, navigating proprietary systems, preserving metadata context, and ensuring long-term access in the face of software drift and platform dependency. In the early 21st century, a press release might begin as a Word doc, cycle through multiple drafts, be emailed to staff, published on a website, and posted on social media, all in a matter of hours. Capturing that full chain of activity is essential to understanding the record in its original context.

Archival practices have adapted to this shifting technological landscape, developing new practices to ensure that the past can be examined with rigor and interpreted with context. This evolution is not merely technical—it is political, historical, and deeply human. When a senator chooses to preserve their legacy in a repository committed to long-term access, it is an act of foresight and public service. It offers future generations insight into the values, debates, and decisions that shaped a given era. But this insight is only possible if the records survive, and survival now depends on action.

A Final Reflection

As historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. observed in a 1974 letter to Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield and Minority Leader Hugh Scott, “If we are going to persuade the nation that Congress plays a vital role in the formation of national policy, Congress will have to cooperate by providing evidence for its contributions.” Congressional archives safeguard historical memory—not just the words themselves, but the provenance that makes them trustworthy. Anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues in Silencing the Past that archives are shaped during the “moment of fact assembly,” when decisions about what to preserve, how to describe it, and what to exclude can influence the contours of collective memory. While individual memories may fade, congressional archival collections anchor our shared understanding of the past by documenting governmental processes. Whether held in acid-free folders or stored on secure servers, these records include the raw material of history, ready to be shaped and assembled by future generations.7

Notes

1. Albert J. Beveridge papers, 1789–1943, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, online finding aid accessed June 10, 2025, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011132.

2. Ibid.

3. Daniel P. Moynihan papers, 1765–2003, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, online finding aid accessed June 10, 2025, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms008066.

4. Ana Radelat, “Burnishing his legacy, Lieberman to leave his official papers to the Library of Congress,” CT Mirror, August 28, 2013, accessed May 20, 2025, https://perma.cc/A7NE-PKTL.

5. “Lieberman Archives Committee Emails,” Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, January 7, 2013, accessed June 5, 2025, https://perma.cc/B7MM-ML4N.

6. “From the archives: A glimpse into the future library and museum,” Arizona State University McCain Library and Museum, accessed June 5, 2025, https://perma.cc/S34N-CYR8.

7. Letter from Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., to Mike Mansfield, May 6, 1974, Administrative Files, Senate Historical Office; Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 26.

|

| 202409 17Constitution Day 2024: The Senate’s Power of Advice and Consent on Nominations

September 17, 2024

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled this important responsibility. This selection of historical documents relates to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

To encourage Americans to learn more about the Constitution, Congress designated September 17—the date in 1787 when delegates to the federal convention signed the Constitution—as Constitution Day.

Throughout the summer of 1787, the framers of the Constitution debated where to place the power to make executive and judicial appointments. Eventually, they settled on the concept of a shared power—the president would make appointments with the “advice and consent” of the Senate. Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution provides that the president "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for.”

The president nominates all federal judges in the judicial branch and specified officers in cabinet-level departments, independent agencies, the military services, the Foreign Service, and uniformed civilian services, as well as U.S. attorneys and U.S. marshals. The vast majority are routinely confirmed, while a small but sometimes highly visible number of nominees fail to receive action or are rejected by the Senate. In its history, the Senate has confirmed 128 Supreme Court nominations and well over 500 cabinet nominations.

The following is a selection of historical documents related to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

John Adams’s Thoughts on Government, 1776

Written in the spring of 1776, John Adams’s Thoughts on Government was first drafted as a letter to North Carolina’s William Hooper, a fellow congressman in the Continental Congress, who had asked Adams for his views on forming a plan of government for North Carolina’s constitution. Adams developed several additional drafts for other colleagues in the following months, and the letter was ultimately published as a pamphlet. Adams’s plan called for three separate branches of government (including a bicameral legislature), which operated within a system of checks and balances, including a shared appointment power. Drawing from similar language in a 1691 Massachusetts’s colonial charter, and referencing a part of the legislative body he called the “Council,” Adams recommended that “The Governor, by and with and not without the Advice and Consent of the Council should nominate and appoint all Judges, Justices, and all other officers civil and military, who should have Commissions signed by the Governor.” Several years later, in 1780, Adams drew from his plan as he helped to write Massachusetts's constitution, which would include the shared appointment power and the phrase “advice and consent.”

In 1787, during the Constitutional Convention, the appointment or nomination clause split the delegates into two factions—those who wanted the executive to have the sole power of appointment, and those who wanted the national legislature, and more specifically the Senate, to have that responsibility. The latter faction followed precedents established by the Articles of Confederation and most of the state constitutions, which granted the legislature the power to make appointments, while the Massachusetts Constitution, with its divided appointment power, provided an alternative model, which was ultimately selected for the U.S. Constitution.

Report of the Grand Committee, September 4, 1787

After debating the appointment clause over the course of several weeks during the Constitutional Convention, the framers eventually settled on the concept of a shared power. Initially, the delegates granted the president the power to appoint the officers of the executive branch and, given that judges’ life-long terms would extend past the authority of any one president, allowed the Senate to appoint members of the judiciary. On September 4, 1787, however, as the proceedings of the convention were nearing conclusion, the Committee of Eleven (also known as the “Grand Committee”)—a special committee consisting of one delegate from each represented state that regularly met to resolve specific disagreements—reported an amended appointment clause. Unanimously adopted on September 7 and based on the Massachusetts constitutional model, which had been recommended earlier during the course of the debates by Massachusetts delegate Nathaniel Gorham, the clause provided that the president shall nominate and, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint the officers of the United States.

Nomination of Alexander Hamilton to be Secretary of the Treasury, 1789

On September 11, 1789, the new federal government under the Constitution took a large step forward. On that day, President George Washington sent his first cabinet nomination to the Senate for its advice and consent. Minutes later, perhaps even before the messenger returned to the president’s office, senators approved unanimously the appointment of Alexander Hamilton to be secretary of the treasury.

Hamilton’s place in history as the Senate’s first consideration and confirmation of a cabinet nominee is fitting as he had participated in the creation of this shared power. At the Constitutional Convention, and in the subsequent campaign to ensure the Constitution’s ratification, Hamilton was convinced that Senate confirmation of nominees would be a welcome check on the president and supported provisions that divided responsibility for appointing government officials between the president and the Senate. Defending the structure of the appointing power in Federalist 76, Hamilton wrote that the “cooperation of the Senate” in nominations “would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from State prejudice, from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity.”

Report of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary Concerning the Nomination of Joseph L. Smith to be Judge of the Superior Court of the Territory of Florida, 1822

The way in which the Senate has exercised its power of advice and consent on nominations has evolved over the course of its history. Before the 1860s, the Senate considered most presidential nominations without referring them to a committee for review or investigation. There were a few exceptions, however, including Joseph L. Smith (nominated by President James Monroe in 1822 to be judge of the Superior Court for the Territory of Florida), who was investigated by the Judiciary Committee, as shown by this report. “It was suggested to the committee that this gentleman had been a colonel in the Army of the United States, and had been lately cashiered upon charges derogatory to his moral character,” the report begins. Subsequently laid out in the report, the committee’s investigation revealed that charges against Smith were refuted by credible witnesses, and he was restored to his rank. “On a full view of all the facts and circumstances,” the report concluded, “the committee could see no objection that ought to operate against the appointment of Col. Smith, and therefore respectfully recommend…that the Senate do advise and consent to the appointment.” Persuaded by the findings of the committee, the full Senate confirmed Smith’s nomination.

Nomination Withdrawal, George H. Williams to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1874

In 1868 the Senate adopted rules to provide for more routine referral of nominations to "appropriate committees," but investigations of judicial nominees typically took place only in cases where the committee received credible allegations of wrongdoing on the part of a nominee. For example, in 1873 the Judiciary Committee, led by Chairman George Edmunds of Vermont, investigated allegations of financial misconduct against Attorney General George H. Williams, who had been nominated to be chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States by President Ulysses S. Grant. After an investigation, the committee informed the president that Williams would likely not be confirmed and Williams asked that his name be withdrawn.

The Senate’s formal order of Williams’s withdrawal begins with, “In Executive Session.” The confirmation of presidential nominations is one of the Senate’s executive (rather than legislative) constitutional duties. This task is therefore performed in executive session, separate from the Senate’s legislative proceedings. Prior to 1929, the Senate rules stipulated that nominations be debated in closed session. These closed executive proceedings were made open on occasion when the Senate voted to ”remove the injunction of secrecy,” and reports of these proceedings were often leaked to the press.

Senator Wilkinson Call to the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on the Nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida, 1890

In its first decade, the Senate established the practice of senatorial courtesy in which senators expected to be consulted on all nominees to federal posts within their states and senators deferred to the wishes of a colleague who objected to an individual nominated to serve in his or her state. If a president insisted on nominating an individual without consultation with or over the objections of a senator, senators merely had to announce in committee or before the full Senate that a nominee was “personally obnoxious” or “personally objectionable” to them without any further explanation. They could depend on the deference of Senate colleagues in rejecting the nominee. While the custom of senatorial courtesy was firmly established by the late 19th century, senatorial objections did not always doom the nomination, especially if a senator was of the opposing party from the president or the Senate majority. In 1890, with Senate Republicans in the majority and Republican Benjamin Harrison in the White House, Judiciary Committee chairman George Edmunds used this form letter to solicit the opinion of Florida Democratic senator Wilkinson Call about the nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida. “I do not consider him to be qualified either mentally or morally for the office of judge,” Call replied. Despite Call’s objection, and the objection of his fellow Florida senator Samuel Pasco (also a Democrat), Swayne’s nomination cleared the Senate.

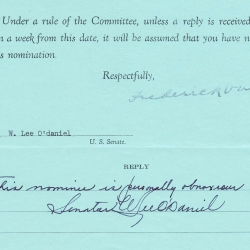

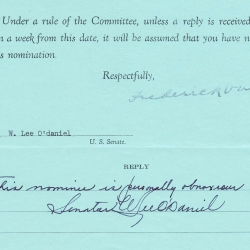

Blue Slip, Signed by Senator W. Lee O’Daniel, 1943

The Judiciary Committee formalized a version of senatorial courtesy through use of the “blue slip,” a blue sheet of paper on which a senator could register support for or opposition to a judicial nominee to serve in his or her state. The process has varied over the years, with different committee chairs giving varied weight to a negative or non-returned blue slip, but the system has endured, providing home-state senators the opportunity to be heard by the Judiciary Committee. During a nomination debate on the Senate floor in 1960, William Proxmire of Wisconsin called senatorial courtesy “the ultimate senatorial weapon,” a “nuclear warhead intercontinental ballistic missile of Senate nomination action.” While there have been changes to the rules and customs governing Senate advice and consent over the past half century—for example, senators no longer announce in the Senate Chamber that a nominee is “personally obnoxious” to them—individual senators continue to influence the nomination and confirmation process.

Hearings on the Nomination of Sandra Day O’Connor to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1981

During the 20th century, Senate committees hired staff to handle nominations and formalized procedures and practices for scrutinizing nominees. In 1939 Felix Frankfurter became the first nominee to appear before the Judiciary Committee to answer questions in a public hearing, and Dean Acheson became the first nominee for secretary of state to testify in open session before the Foreign Relations Committee 10 years later. By the 1950s, committees began routinely holding public hearings and requiring nominees to appear in person. By the 1990s, Judiciary Committee staff included an investigator who worked on nominations. In 1981 Sandra Day O’Connor of Arizona appeared before the Judiciary Committee as the first woman nominated to the serve on the Supreme Court. O’Connor’s nomination hearing was the first to be televised, and today all committee nomination hearings are broadcast or live-streamed on the Internet.

Today, committees have the option of reporting a nominee to the full Senate with a recommendation to approve ("reported favorably"), with a recommendation to not approve ("reported adversely"), or with no recommendation. Reporting adversely—sometimes because senatorial courtesy was not observed—has become rare. Since the 1970s, committees have on occasion, though still infrequently, voted not to report a nominee to the full Senate, effectively killing the nomination. More frequently, committees do not act on nominations that do not have majority support to move forward.

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution in 1787. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled its constitutional responsibility of advice and consent, playing a role both in the selection and confirmation of nominees.

|

| 202404 06Treasures from the Senate Archives: The Long Journey to Quorum

April 06, 2024

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress. This year’s collection of treasures from the Senate Archives along with correspondence from manuscript collections tells the story of this very event—the Senate’s long journey to a quorum in the late winter and early spring of 1789.

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress. This year’s collection of treasures from the Senate Archives along with correspondence from manuscript collections tells the story of this very event—the Senate’s long journey to a quorum in the late winter and early spring of 1789.

The Framers of the Constitution included a formula for its ratification. As stated in Article VII: “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution.” When the necessary ninth state—New Hampshire—ratified the Constitution on June 21, 1788, the Congress under the Articles of Confederation began the transition to form a new federal government. On September 13, that soon-to-expire Confederation Congress issued an ordinance giving states authority to elect their first senators and set the convening date for the First Federal Congress—March 4, 1789. As it turned out, that was the easy part.1

When the convening date arrived, the First Congress was to meet in the newly refurbished and renamed Federal Hall in New York City to count the electoral votes for president and vice president, inaugurate the winners, and proceed with its business. Writing to his wife that momentous day, Pennsylvania senator Robert Morris described the dramatic transition taking place in the city: “Last Night they fired 13 Canon [sic] from the Battery here over the Funeral of the Confederation & this Morning they Saluted the New Government with Eleven Cannon being one for each of the States that have adopted the Constitution,” he wrote. (Rhode Island and North Carolina had not yet ratified the Constitution.) “[R]inging of Bells & Crowds of People at the Meeting of Congress gave the air of a grand Festival to the 4th of March 1789 which no doubt will hereafter be Celebrated as a New Era in the Annals of the World.” The New York Daily Advertiser reported that “a general joy pervaded the whole city on this great, important and memorable event; every countenance testified a hope that under the auspices of the new government, commerce would again thrive … and peace and prosperity adorn our land.”2

The exultation soon transitioned to disappointment, however, when both houses fell short of reaching the quorum required by the Constitution to conduct their business (30 representatives and 12 senators). Only 13 of the 59 representatives and only 8 of the 22 senators from the 11 states were present to offer their credentials (certificates of election) and be sworn in. "The number not being sufficient to constitute a quorum, they adjourned," reads the first entry in the Senate Journal.3

“We are in hopes these Numbers will Appear tomorrow,” an optimistic Morris wrote. News reports were likewise hopeful. “It is expected that a sufficient number to form a quorum will arrive this evening. Should that be the case the votes for President and Vice-President will be counted to-morrow,” the New York correspondent to the Massachusetts Centinel explained. In the subsequent days, the ongoing delay diminished such confident expectations and tested the patience of an anticipative country, including the punctual group of eight senators. Day after day, these senators appeared in the Senate Chamber only to be disappointed, harboring growing concerns of the government’s inability to operate.4

The image of a government paralyzed by absenteeism was all too familiar. The Confederation Congress had encountered similar problems, and in its final months, that legislature remained practically powerless to conduct business due to a lack of quorum. Thus, when only eight of the senators elected to the new federal government under the Constitution presented themselves on March 4, many feared a continuation of the old difficulty. "The members of the First Federal Congress who were on hand in New York on the appointed first day of the session were anxious to avoid any image of impotence caused by the lack of a quorum,” one historian explained. “They hoped that the new government could begin its work promptly, conveying an impression of the seriousness of their attention to duty to the expectant public." When a quorum failed to materialize over the next few days, those who had arrived pleaded with their missing colleagues in a letter. "We apprehend,” they wrote, “that no arguments are necessary to evince to you the indispensable necessity of putting the Government into immediate operation; and, therefore earnestly request, that you will be so obliging as to attend as soon as possible."5

Frustration and resentment grew as another week passed, and another, and still no quorum. “We earnestly request your immediate attendance,” they implored the absentees on March 18. Pennsylvania senator William Maclay complained in a letter to his friend Benjamin Rush, “I have never felt greater Mortification in my life[;] to be so long here with the Eyes of all the World on Us & to do nothing, is terrible.” In a later letter he added, “It is greatly to be lamented, That Men should pay so little regard to the important appointments that have devolved on them.” Members of the House of Representatives were likewise discouraged. “I am inclined to believe that the languor of the old Confederation is transfused into the members of the new Congress,” Massachusetts representative Fisher Ames wrote. “We lose credit, spirit, every thing. The public will forget the government before it is born.”6

The senators grew hopeful when Senator William Paterson of New Jersey appeared on March 19, followed soon thereafter by Richard Bassett of Delaware on the 21st and Jonathan Elmer of New Jersey on the 28th. Now 11 strong, they were still one man short of a quorum. Bassett earnestly wrote to his absent colleague, Delaware senator George Read, expressing concern that the House would reach a quorum before the Senate:

Where the Twelfth Member is to come from is not yet known, unless you can be prevailed on to Move forward—The Members of the Senate are very uneasy, and press me Exceedingly to urge the Necessity of your Making all Possible Dispatch in coming forward, as it is apprehended next week will bring forward a Sufficient Number of the other Branch to proceed, and they wish not to have the fault lain at our Door.7

Charles Thomson, who had been the secretary of the Continental Congress and was serving in a similar capacity during this interim period, also made a plea to Read, writing that he was “extremely mortified” that Read had not traveled to New York with Bassett, and expressing his fears that the delay would fuel opposition to the new government:

Those who feel for the honor and are solicitous for the happiness of this country are pained to the heart at the dilatory attendance of the members appointed to form the two houses while those who are averse to the new constitution and those who are unfriendly to the liberty & consequently to the happiness and prosperity of this country, exult at our languor & inattention to public concerns & flatter themselves that we shall continue as we have been for some time past the scoff of our enemies.…What must the world think of us?8

Despite the frustrations, blame, and admonishment, there were some well-founded and justifiable reasons for the delayed arrival of members, the most significant of these being the challenges of wintertime travel in the 18th century. The trip from Boston to New York City typically took six days, but during the winter, that journey could take two weeks or more. Senators navigated treacherous roads in wagons or sleighs and often were forced to seek refuge at nearby farms when conditions grew too dangerous. “There was no possibility of conveying [us] in February to new-york, by water or on wheels,” complained Massachusetts representative Elbridge Gerry. Senators from Maryland or Virginia endured weeks-long travel on horseback or in rickety coaches, braving cold and icy waters at five separate ferry crossings. Southerners, traveling mostly by sea, faced the greatest hazards of all. One southern member was delayed for weeks when his ship foundered off the Delaware coast.9

In addition to arduous weather and travel conditions, there were personal and political reasons for the delayed arrival of members of the new Congress. George Read, who finally arrived on April 13, was likely delayed due to sickness, as he later wrote that he had been unwell during this time. Correspondence from this period reveals that several others were delayed by illness, including Senator Elmer and Massachusetts senator Tristram Dalton. Politics also played a role. New York’s state legislature was deadlocked over candidates for months and did not send senators to Federal Hall until July 1789.10

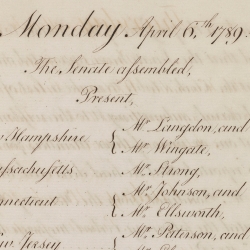

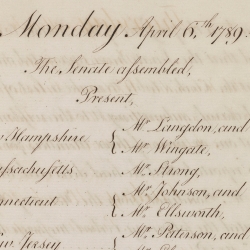

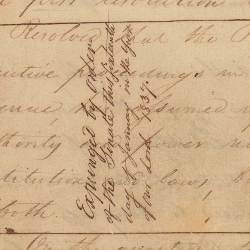

On April 1, the attending senators’ fears were realized when the House became the first of the two chambers to achieve a quorum. Five days later, on April 6, the necessary 12th senator finally arrived, Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee. The Senate then turned to the important business of helping to formalize the new national government by declaring the winner of its first presidential election. “Being a Quorum, consisting of a majority of the whole number of Senators of the United States. The Credentials of the afore mentioned members were read and ordered to be filed,” the Senate Journal reads. “The Senate proceeded by ballot to the choice of a President [pro tempore], for the sole purpose of opening and counting the votes for President of the United States.”11

Thankfully, the inauspicious beginning of the First Congress’s first session would not be repeated, as subsequent sessions saw some improvement in punctuality. In January 1790, at the start of the second session, a more experienced Senate reduced its convening delay to only two days. Finally, at the beginning of the third session in December 1790, the necessary quorum appeared on time and the Senate got down to business as planned. With the new government firmly established and transportation and infrastructure gradually improving, summoning a quorum would prove less of a challenge for future Congresses.

Notes

1. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904–37), 34:523, September 13, 1788.

2. Robert Morris to Mary Morris, March 4, 1789, and New York Daily Advertiser, March 5, 1789, included in Charlene Bangs Bickford et al., eds., Correspondence: First Session, March–May 1789, vol. 15 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 15–16.

3. Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., March 4, 1789.

4. Robert Morris to Mary Morris, March 4, 1789, and Massachusetts Centinel, March 14, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:15–17.

5. Charlene Bangs Bickford, “‘Public Attention Is Very Much Fixed on the Proceedings of the New Congress’: The First Federal Congress Organizes Itself,” in Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1999), 139; Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, March 11, 1789. Various Papers 1789–1982, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

6. Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, March 18, 1789. Various Papers 1789–1982, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; William Maclay to Benjamin Rush, March 19, 1789 and March 26, 1789, and Fisher Ames to George R. Minot, March 25, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:78, 126, 134.

7. Richard Bassett to George Read, March 21, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:86.

8. Charles Thomson to George Read, March 21, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:90–91.

9. A good description of the hazards of travel to New York at this time is included Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:19–22; Elbridge Gerry to James Warren, March 22, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:92.

10. William Thompson Read, Life and Correspondence of George Read: A Signer of the Declaration of Independence, with Notices of Some of His Contemporaries (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Company, 1870) 473; "New York’s First Senators: Late to Their Own Party," National Archives' Pieces of History blog, accessed March 26, 2024, https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2014/07/26/new-yorks-first-senators-late-to-their-own-party/.

11. Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., April 6, 1789.

|

| 202304 04Treasures from the Senate Archives: Legislative-Executive Relations

April 04, 2023

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the selection of historic records featured in this month’s “Senate Stories,” which highlight the complex relationship between the Senate and the president.

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the selection of historic records featured in this month’s “Senate Stories,” which highlight the complex relationship between the Senate and the president.

Among the foundational principles of the U.S. Constitution is the separation of powers. In establishing three distinct branches of government—legislative, executive, and judicial—the Constitution divides authority to create the law, implement and enforce the law, and interpret the law. At the same time, many powers exercised by one branch may be shared with another. This system of checks and balances invites both compromise and conflict among the branches, especially between the legislative and executive, and prevents the consolidation of power in any single branch. For example, the Senate’s “advice and consent” is required for executive functions such as nominations and treaties. Conversely, the president has the power to veto legislation; however, Congress may overturn the veto with a two-thirds majority of those present and voting in both houses.1

The constitutional structure that provides for checks and balances is expansive and complex by design, generating an interdependence between the Senate and the executive branch that, combined with transient political interests, has historically demonstrated moments of high conflict as well as examples of great cooperation. This collection of historic documents from the Senate’s archives highlights the collaborations and the struggles that have defined the relationship between the Senate and the president. Each document, while capturing a specific moment in time with unique political conditions at play, also provides a broader view of the constitutional system of government in action, specifically the foundational principle of separation of powers and the complex system of checks and balances.

George Washington's First Inaugural Address, 1789

When George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the United States on April 30, 1789, he delivered this address to a joint session of Congress, assembled in the Senate Chamber in New York City’s Federal Hall. While this first occasion was not the public event we have come to expect, Washington's speech nevertheless established the enduring tradition of presidential inaugural addresses. Early presidential messages, including inaugural addresses and annual messages (now known as State of the Union addresses), are included in Senate records at the National Archives.

Although noting his constitutional directive as president "to recommend to your consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient," Washington refrained from detailing his policy preferences regarding legislation. Rather, on the occasion of his inaugural, he stated his confidence in the abilities of the legislators, insisting, "It will be…far more congenial with the feelings which actuate me, to substitute, in place of a recommendation of particular measures, the tribute that is due to the talents, the rectitude, and the patriotism which adorn the characters selected to devise and adopt them."

Message from President Thomas Jefferson to Congress Regarding the Louisiana Purchase, 1804

Treaty powers are among those shared by the president and the Senate. The Constitution provides that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur" (Article II, section 2). In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson's administration negotiated a treaty with France by which the United States purchased the vast Louisiana Territory. Questions arose concerning the constitutionality of the purchase, but Jefferson and his supporters successfully justified the legality of the acquisition. On October 20, 1803, the Senate approved the treaty for ratification by a vote of 24 to 7. The territory, which encompassed more than 800,000 square miles of land, now makes up 15 states stretching from Louisiana to Montana. In this congratulatory message to Congress dated January 16, 1804, President Jefferson reported on the formal transfer of the land to the United States and referenced the December 20, 1803, proclamation announcing to the residents of the territory the transfer of national authority.

Page from the Senate Journal Showing the Expungement of a Resolution to Censure President Andrew Jackson, 1834

The March 28, 1834, censure of President Andrew Jackson represents a notably contentious episode in the executive-legislative relationship. For two years, Democratic president Andrew Jackson had clashed with Senator Henry Clay and his allies over the congressionally chartered Bank of the United States. The dispute came to a head when President Jackson, who had opposed the creation of the Bank, ordered the removal of federal deposits from the Bank to be distributed to several state banks. When his first Treasury secretary refused to do so, Jackson fired him during a Senate recess and appointed a new Treasury secretary, who carried out his orders. Senator Clay and his allies, who supported the Bank, believed that President Jackson did not have the constitutional authority to take such action, and they found the explanation given for moving the federal deposits “unsatisfactory and insufficient.” Clay introduced the resolution to censure the president, charging that Jackson had “assumed the exercise of a power over the Treasury of the United States not granted him by the Constitution and laws.” After extensive debate, the censure resolution passed. Jackson responded by submitting to the Senate a 100-page message arguing that the Senate did not have the authority to censure the president. The Senate again rebuffed the president by refusing to print the lengthy message in its Journal.2

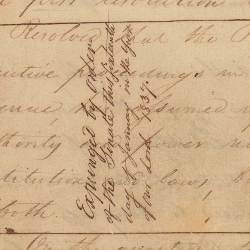

Over the next three years, Missouri Democrat and Jackson ally Thomas Hart Benton campaigned to expunge the censure resolution from the Senate Journal. In January 1837, after Democrats regained the majority in the Senate, Senator Benton succeeded. On January 16, the secretary of the Senate carried the 1834 Journal into the Senate Chamber, drew careful lines around the text of the censure resolution, and wrote, “Expunged by order of the Senate."

President Abraham Lincoln's Nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to be Lieutenant General of the U.S. Army, 1864

Like treaty powers, the Constitution requires that the Senate serve as a check on the president's nomination authority. The president nominates federal judges, members of the cabinet, and military officials, among others, whose nominations are confirmed with the advice and consent of the Senate. This remarkable document dated February 29, 1864, representing a critical moment in the Civil War, is President Abraham Lincoln's nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to be lieutenant general of the U.S. Army, at the time the United States’ highest military rank. Previously, only two men had achieved that rank—George Washington and Winfield Scott—and Scott’s had been a brevet promotion. To facilitate Grant’s nomination and ensure his superior status among military officers, Congress passed a bill to revive the grade of lieutenant general and authorize the president "to appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, a lieutenant-general, to be selected among those officers in the military service of the United States . . . most distinguished for courage, skill, and ability." The Senate confirmed Lincoln's nomination of Grant on March 2, 1864.

Letter from President Woodrow Wilson to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, 1919

A unique event in legislative-executive relations occurred on August 19, 1919, when President Woodrow Wilson offered testimony before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations on the Treaty of Versailles, then under consideration by the committee. The meeting, convened in the East Room of the White House, stood “in contradiction of the precedents of more than a century,” the Atlanta Constitution reported, noting the rarity of a president offering testimony before a congressional committee.3

The Treaty of Versailles ended military actions against Germany in World War I and created the League of Nations, an international organization designed to prevent another world war. President Wilson had led the U.S. delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and had been a principal architect of the treaty. For months, Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Henry Cabot Lodge had encouraged the president to seek the advice of the Senate while negotiating the treaty’s terms, but Wilson chose to negotiate on his own. Personally invested in the treaty’s adoption, the president hand-delivered it to the Senate on July 10, 1919, and urged its approval for ratification in an unusual speech before the full Senate.

Under Senate rules, the treaty went to the Foreign Relations Committee for consideration, which held public hearings from July 31 to September 12, 1919. Among the most vocal critics of the proposed treaty was Lodge, who was also the Senate majority leader. Lodge opposed several elements of the treaty, particularly those related to U.S. participation in the League of Nations. On behalf of the Foreign Relations Committee, Lodge asked Wilson to meet with the committee to answer senators’ questions. With this letter, President Wilson agreed to Lodge's request and proposed the August 19 date at the White House.

Ultimately, Lodge’s committee insisted on a number of “reservations” to the treaty, but Wilson and Senate proponents of the treaty were unwilling to compromise on terms. Consequently, on November 19, 1919, for the first time in its history, the Senate rejected a peace treaty.

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, 1973

Under the Constitution, the president is permitted to veto legislative acts, but Congress has the authority to override presidential vetoes by two-thirds majorities of both houses. This document provides a comprehensive example of these constitutional checks and balances in action. In 1973 Congress passed S.518, which sought to abolish the offices of the director and deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget and reestablish those positions with a new requirement that they be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. The bill’s proponents argued that because these positions had evolved to wield significant power, they ought to be subject to Senate confirmation.

President Richard Nixon vetoed the bill on May 18, claiming it to be unconstitutional. “This step would be a grave violation of the fundamental doctrine of separation of powers,” Nixon stated. While the Senate achieved the necessary two-thirds majority to override the veto, the House did not, and Nixon’s veto was sustained. Congressional efforts to override Nixon’s veto were recorded by the secretary of the Senate and clerk of the House of Representatives on the reverse side of the bill.

The system of checks and balances set forth by the Constitution is a complex one, creating a legislative-executive relationship that is sometimes adversarial and at other times cooperative, but always interdependent. Illustrating the Senate's broad-ranging responsibilities and the integral role the Senate has played in this constitutional system, these treasured documents from the Senate’s archives help us to gain a better understanding of the conflicts and compromises that have historically defined the relationship between the Senate and the president.

Notes

1. Matthew E. Glassman, "Separation of Powers: An Overview," Congressional Research Service, R44334, updated January 8, 2016, 2.

2. Senate Journal, 25th Cong., 2nd sess., March 28, 1834, 197.

3. “Wilson Meets Senators in Wordy Duel,” Atlanta Constitution, August 20, 1919, 1.

|

| 202204 04Treasures from the Senate Archives

April 04, 2022

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the historic records of Senate committees highlighted in this month's “Senate Stories.”

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the historic records of Senate committees highlighted in this month's “Senate Stories.”

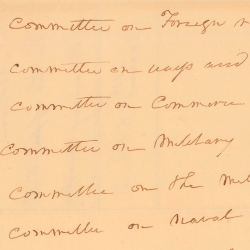

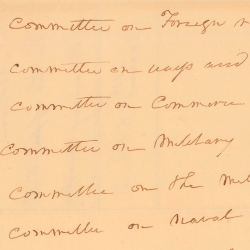

In December 1816, the Senate established its first permanent standing committees. Prior to that time, the Senate had relied on ad hoc or temporary committees to sift and refine legislative proposals, to consider nominations and treaties, and to fulfill other constitutionally designated rights and responsibilities. The demands of a growing nation and a war with Great Britain prompted the Senate to revise its procedures. On December 10, 1816, senators approved a resolution to establish 11 permanent standing committees with jurisdictions over designated areas such as finance, foreign relations, military affairs, commerce, and the judiciary.

The records of these early ad hoc and standing committees, and all subsequent committees, represent the majority of official Senate records preserved and housed at the Center for Legislative Archives at the National Archives and Records Administration. This large collection of archived Senate committee records offers ample evidence of the important work done by each committee.

The Center for Legislative Archives preserves the oldest and most historically significant congressional records in its Treasure Vault, including records created during the First Congress, which convened in 1789. Along with the first Senate Journals, there are bills, war and censure resolutions, petitions, presidential messages, nominations, and proposed constitutional amendments. The simple, handwritten 1816 resolution creating the standing committees is among these precious documents. The fact that these documents were gathered and preserved long before the creation of the federal archives system makes their survival all the more extraordinary.

The following Senate documents from the Treasure Vault highlight the work of three of the Senate's original standing committees: Pensions, Commerce and Manufactures, and Judiciary. Each document captures a moment in time while providing a window into the operation of Senate committees as constitutional government-in-action.

Petition from Mary Colcord, 32nd Congress (1852)

In 1818 Congress passed a pension bill to provide financial support to Revolutionary War veterans. The oversight of this support (sometimes the only form of income for veterans and their families) was managed by the Committee on Pensions, one of the standing committees created in 1816. The committee’s archival records include applications like this one submitted to the Senate in 1852 by 81-year-old Mary Colcord. To document the service of her father, Bradstreet Wiggin, during the Revolutionary War, Colcord submitted the handwritten diary of Samuel Leavitt, a contemporary of her father from the same New Hampshire town who had served in the same company. The diary records Leavitt's service in the New Hampshire militia in 1780. It was given to the committee by Colcord presumably as evidence of her father's service, although she indicates that her father served during a different year. Consequently, the Senate’s archival collection has been enriched by this rare and historic record detailing a common soldier’s experience during the Revolutionary War. Although Colcord's claim, submitted more than 70 years after the war ended, was ultimately rejected by the committee, Congress did continue to pay Revolutionary War pensions as late as 1906.1

Following a congressional reorganization in 1946, the Senate moved the management of all war pensions to the Committee on Finance. In 1970 the Senate formed a Committee on Veterans Affairs and consolidated the oversight of all veterans’ issues, including pensions, under the jurisdiction of the new committee.

Memorial of Inhabitants of Los Angeles County, California, praying for establishment of a port of entry in that county, 31st Congress (1850)

The importance of commerce in national affairs led to creation of the Committee on Commerce and Manufactures in 1816. Regulating commerce is an expressed congressional responsibility, so it is not surprising to find among the committee’s papers this memorial, a form of petition, of the residents of Los Angeles County, California, part of the newly acquired Mexican Cession region, asking for the establishment of a port of entry in that county. This document, dated July 1850, was referred to the Commerce Committee amidst the debate over the Compromise of 1850, which resulted in establishing statehood for California that same year. Rapid progress in technology, communication, and commercial development in the 19th and 20th centuries prompted the Commerce Committee to split into various smaller committees to handle an ever-expanding legislative and oversight caseload. Two legislative reorganizations, in the 1940s and 1970s, consolidated most of these committees under the jurisdiction of today’s Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s message regarding national health, 76th Congress (1939)

On January 23, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a four-page presidential message to Congress calling for the creation of a “national health program … to make available in all parts of our country and for all groups of our people the scientific knowledge and skill at our command to prevent and care for sickness and disability.” Presidential messages, including the annual State of the Union Address, serve as vehicles for the president to raise urgent matters with Congress. The subjects of public health and health care assistance reflect the expansion of the role of the federal government in response to the national crisis of the Great Depression. Perhaps because of the references to science and economic loss, as well as the interstate nature of the proposed program, the message was referred to the Committee on Commerce.

Petition from Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and others, 42nd Congress (1871)

The First Amendment grants individuals the right to petition Congress to redress grievances or to seek the assistance of the government. Petitions allow ordinary citizens to express their views to their elected representatives. Managing these petitions became the responsibility of Senate committees, including the Judiciary Committee, which was established as a permanent committee in 1816 to oversee the courts, judicial proceedings, and constitutional matters. This petition is typical of thousands received by the committee supporting woman suffrage. It is particularly noteworthy because it includes the signatures of leading suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony who ask that they “be permitted in person, and on behalf of the thousands of other women who are petitioning Congress … to be heard … before the Senate and House.” Suffragists first testified before a Senate committee in 1878 and continued to do so until the Senate passed the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919, which granted female suffrage upon ratification in 1920.

President Lyndon B. Johnson's nomination of Thurgood Marshall to be associate justice of the Supreme Court, 90th Congress (1967)

The Senate has the constitutional power to advise and consent on presidential nominations, and Senate committees play an important role in that process. Before the 1860s, the Senate considered most nominations without referring them to a committee for review or investigation, although the Judiciary Committee did consider some nominees as early as the 1830s. In 1868 the Senate adopted rules to provide for more routine referral of nominations to "appropriate committees," but investigations of judicial nominees were rare. By the early 20th century, the Judiciary Committee had become much more integral to the nomination process, and by the mid-to-late 20th century, nominees were regularly testifying before the committee. This featured record of the Judiciary Committee, President Lyndon B. Johnson's 1967 nomination of Thurgood Marshall to be an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, documents the historic appointment of the first African American Supreme Court justice.

First Issue of MAD magazine, from the investigative files of the Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, 82nd Congress (1952)

The creation of standing committees enabled the Senate to better pursue its implied constitutional powers of oversight and investigation to inform legislation or to bring attention to important matters. Since World War II, congressional investigations into allegations of wrongdoing, fiscal mismanagement, national security, corporate malpractice, and social and economic issues of concern have resulted in better legislation, taxpayer savings, consumer protections, and stronger ethics laws. In most cases, standing committees serve as the Senate's principal investigative arm, but the Senate also has entrusted this responsibility to special and select committees.

The broad and extensive nature of these investigations has created an archival record that includes an interesting and unusual assortment of documents and artifacts. Among these is a collection of early 1950s comic books and youth publications, including 12 of the first 13 issues of MAD magazine. Popular films like Nicholas Ray’s 1955 Rebel Without a Cause dramatized public concern about wayward youths and juvenile violence, prompting a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee to launch an inquiry. That investigation explored the role of popular culture, including publications like MAD magazine, in shaping adolescent behaviors and attitudes. The subcommittee continued to investigate the issue of juvenile delinquency for many years.

Illinois senator Everett M. Dirksen once remarked that “floor debate on a bill can be likened to an iceberg…the top shows, but the major part is underneath. The work of the committee is the large part that is not seen by the public.”2 The archived records of Senate committees reflect the behind-the-scenes work of senators and staff. They demonstrate the routine, the historical, the touchingly personal, and even the whimsical nature of committee work. Through these records we gain a better understanding of the history of the Senate and the ever-evolving work of Congress.

Notes

1. History of the Finance Committee, United States Senate, S. Doc. 97-5, 97th Cong., 1st sess., 1981, 47.

2. "What a United States Senator Does, by Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen, Republican Minority Leader," undated, included in the biographical files of the Senate Historical Office.

|

| 202104 01Saving Senate Records

April 01, 2021