| 202503 25The Senate Spares the Belmont House

March 25, 2025

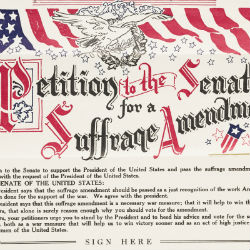

As the Senate sought to expand its office space during the mid-20th century, many neighboring structures were targeted for demolition. One such example was the historic Belmont House, headquarters of the National Woman’s Party. Ultimately, through the efforts of advocates, staffers, and senators themselves, the Senate came to see the Belmont House, with its unique connection to women's history, as a historic structure worthy of preservation.

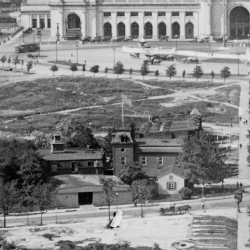

In the early 1950s, Washington D.C.’s “Square 725” was a vibrant city block comprising private residences, organizations, and businesses just blocks to the northeast of the Capitol. Dozens of individuals and families called this place home. Schott’s Alley cut across the heart of Square 725 lined on either side by about 10 residences, some of which were renovated into “deluxe living quarters” by developers in 1954. Locals shopped for groceries at Lucille’s Delicatessen, located at 135 C Street NE. Two doors down at 131 C. Street NE, Rev. Alfred Terry held religious services on Sundays at the First Spiritualist Church and sponsored seances and classes. The Galena and The Merrick, at 132 and 138 B. Street NE respectively, were both lodging homes primarily for women who worked as clerks, stenographers, and typists, many of whom were employed by the Senate. In other words, Square 725 was a lively community much like any other in the District. The U.S. Senate was about to dramatically change it.1

Following World War II, senators sought to modernize their institution, approving the Legislative Reorganization Act in 1946 that provided for the hiring of professional, non-partisan staff. It wasn’t long before the Senate needed additional office space to accommodate that staff. Planning began shortly thereafter to erect a second office building (the first Senate Office Building—today's Russell Senate Office Building—opened in 1909), and the logical location was Square 725. Following the pattern established when the first Senate Office Building had been constructed, the Senate planned to purchase the land and demolish the existing neighborhood to make way for a new structure. By the end of 1949, the Senate had acquired the western half of Square 725, cleared much of the land, and approved a new building design, but construction was delayed. The groundbreaking ceremony for the Senate’s new office building finally took place on January 26, 1955. While waiting on construction, senators discussed acquiring and clearing the entirety of Square 725 for potential building expansion at a later date.

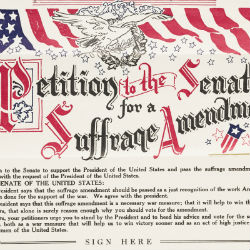

Clearing Square 725, however, would not be so easy. At the corner of Constitution Avenue and 2nd Street NE sat the historic Belmont House, headquarters for the National Woman’s Party (NWP) since 1929. The NWP, one of the most influential American women’s rights organizations of the early 20th century, was credited with helping to secure women’s suffrage and protections from employment discrimination. Belmont House had also been the scene of historic events connected to the Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812. Preservationists considered the structure to be “one of the cornerstones of American heritage on Capitol Hill.”2

The Washington Post reported in early 1956 that the most likely outcome for the entire square was full acquisition by the Senate, potentially by seizure under eminent domain laws, with all structures eventually to be demolished. With legislation for full acquisition pending, the Senate Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds of the Committee on Public Works held hearings in May 1956 to hear from some of the affected parties. Recognizing that the Belmont House was endangered, the NWP rallied in opposition and strongly protested in their testimony.3

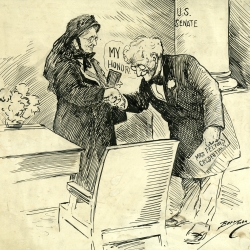

During the first moments of the 1956 hearings, Senator Carl Hayden of Arizona, a champion of women’s rights and suffrage even before his Senate service, testified as a witness and offered to amend the pending legislation to exclude the Belmont House, but only if “there should be a quantity of proof before the committee as to the historical value of the property.” In response to Hayden’s offer, nearly a dozen NWP supporters testified to the structure’s unique history, including Augusta Wood Dale, widow of Senator Porter Dale and former Belmont House owner. Most witnesses focused on the house’s age and its connection to early American heritage.4

Dating to about 1800, the house was rented from 1801 to 1813 by Albert Gallatin, secretary of the treasury under President Thomas Jefferson and primary negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty. During the War of 1812, the house gained some notoriety, as conveyed by several witnesses who told the story of shots being fired from the house upon advancing British troops who then burned part of the structure before moving on to burn the Capitol. Several witnesses testified to the historical integrity of the structure and lamented the destruction of historic buildings throughout the District, including the Old Brick Capitol that had been razed to make way for the Supreme Court Building in the 1930s. All throughout the testimony, the building’s connection to the NWP and women’s history was hardly mentioned.5

Despite the testimony at the 1956 hearings demonstrating the historical value of Belmont House, the legislation to acquire Square 725 continued to threaten the house’s existence for the next two years. NWP leader Alice Paul, speaking to the Washington Post, expressed her frustration with the long delay, equating the ongoing threat of demolition to congressional harassment. With full Square 725 acquisition still pending on June 23, 1958, Senator Dennis Chavez of New Mexico, chair of the Committee on Public Works, finally introduced an amendment, penned by Senator Hayden, that excluded seven lots, described as “property in Schott’s Alley and other property,” from the proposed acquisition. In a statement accompanying his amendment, Senator Hayden indicated that he understood acquisition would proceed if “the bill is amended so as to exclude the real property occupied by the NWP.” With the amendment adopted, the bill passed easily. The Senate had spared the Belmont House, for now.6

In 1967, less than 10 years after the opening of the Senate’s second office building (later named the Dirksen Senate Office Building), Senator Jennings Randolph of West Virginia proclaimed that the Senate was “long since past a critical stage” regarding office space. A Committee on Public Works survey concluded that 72 senators and 24 committees required additional space and recommended immediate acquisition of the remainder of Square 725—including portions of the NWP’s property—to build a third office building (later named the Hart Senate Office Building). The Belmont House was again in demolition crosshairs.7

The Senate quietly moved forward with these plans and, unbeknownst to the NWP, passed a bill to acquire the remaining sections of Square 725 by a vote of 42-33 in April 1968. The Senate bill called for condemning two-thirds of the Belmont House property to make way for an access driveway for the newest Senate office building. When the House considered the bill that September, NWP leadership finally learned of the plan and rushed to make their voices heard. NWP leaders fired off telegrams, visited House of Representative offices, and spoke directly to the media over the course of about two weeks as the bill neared House approval. Joining the NWP in its crusade to save Belmont House was “a new coalition of college girls and radicals,” according to the Washington Post, including the newly created National Organization of Women and members of the National Women’s Liberation Group. The house’s connection to women’s history was now front and center. To the relief of NWP leadership, the House rejected the legislation, and the Belmont House was spared for a second time.8

The Belmont House’s future brightened significantly between 1972 and 1974. First, Congress authorized the purchase of some of the NWP’s peripheral property, providing funds for the organization to discharge its debts. Next, the National Capital Planning Commission worked with the National Park Service (NPS) to have the house listed on the National Register of Historical Places, thus formally recognizing the structure’s national historical significance for the first time. Writing in support of the listing, an unsigned NPS commenter noted, “They’ve torn down all adjacent housing and I’m sure that they’ve got this in mind next.” The Belmont House also benefitted from increased attention to women’s rights. In 1972 the Senate overwhelmingly approved the Equal Rights Amendment, to prohibit discrimination on account of sex, by a vote of 84-8. The House had already passed the bill, and it was sent to the states for ratification.9

In 1974 a Senate staff member kickstarted legislation to permanently save the Belmont House. Then-NWP National Chairman Elizabeth Chittick approached Frankie Sue Del Papa, a law student in her third year working as a staff member in the office of Senator Alan Bible of Nevada. Del Papa created a law school project, with the blessing of Senator Bible, to draft legislation that would, in her words, “save the Sewall-Belmont House from eminent domain.” Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington introduced the legislation on March 19, 1974, and called for its passage because “the women’s rights movement is not itself represented” within the National Park Service. Senator Bible wholly supported the bill and, as chairman of the Subcommittee on Parks and Recreation of the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, scheduled hearings for May 31, 1974.10

Many senators testified at the subcommittee hearing in favor of permanently protecting the Belmont House because of its connections to women’s history. Senator Jackson provided the context and impetus for such action: “What a fitting statement by Congress to create a women’s history monument as the Equal Rights Amendment marched towards certain ratification.” Senator Howard Metzenbaum of Ohio, who co-sponsored the bill, echoed this sentiment while also drawing a metaphor about the women’s rights movement and the Belmont House itself: “In this house, much of the history of the woman's movement was made, fragile gains cementing one another, somewhat as the brick walls of the kitchen were laid with mortar made from oyster shells.” Del Papa’s testimony underscored the importance of the Belmont house as a symbol of women’s history. “Previous Senate committees have not always been so thoughtful of this neighboring historic house,” she explained, reminding senators the house was nearly razed in the 1950s, before praising “some farsighted Senators [who] sought to preserve for posterity this symbol of, and monument to, the women’s rights movement.”11

On October 4, 1974, a favorable report from Senator Bible of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs recommended passage of an NPS omnibus bill creating six park units, amended to include the “Sewall-Belmont House National Historical Site” as a “cooperative agreement to assist in the preservation and interpretation of such house.” Four days later, the Senate passed the measure without debate, and it was signed into law by President Gerald Ford later that month. According to Del Papa, significant support in the Senate came from Senator Bible’s direct appeal to other members. 12

Today the Belmont House stands proudly at the corner of 2nd Street NE and Constitution Avenue—the only remaining structure of the once vibrant Square 725. Sitting at the Capitol’s periphery since 1800, the Belmont House was associated with historically significant events and people, but it was its connection to the women’s suffrage movement that ultimately saved it from the wrecking ball. According to Elizabeth Chittick, the Belmont House is “a place where women may find their identity with the history of the past in their march for equal rights.” Senator Jackson brought this same sentiment to the Senate floor in 1974, stating the Belmont House represented “contributions and efforts which women have made to the development of this nation and in awakening social conscience for human rights.” This perspective took years to form within the Senate, but largely thanks to efforts by the NWP and senators who listened, the Belmont House became central to American history and heritage at a particularly significant time for the advancement of women’s rights. Today, under the protections of the National Park Service, the Belmont House, now the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, serves as a reminder of that powerful political heritage. 13

Notes

1. Senate Committee on Public Works, Extension of Capitol Grounds: Hearings on S.3704, 84th Cong., 2nd sess., May 21–22, 1956 (hereafter referred to as “1956 Hearings”), 9; Population Schedule for Washington D.C., ED 1-785, Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950, Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; “Rooms Furnished-N.E.,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), August 15, 1950.

2. Note that the “Belmont House” has been known by many names over the years. As of 2025, it is formally known as the “Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument.” It has also been known as the Sewall House (1800–1929), the Alva Belmont House (1929–1972), and the Sewall-Belmont House and Museum (1972–2016). This essay refers to the structure as the “Belmont House” for simplicity and because this was the terminology typically used by senators from the 1940s through the 1970s; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, Hearing held before Subcommittee on Fiscal Affairs of the Committee on the District of Columbia, S.2306, Relating to the Exemption of the National Woman’s Party, Inc. from Taxation in D.C., 86th Cong., 2nd sess., January 19, 1960 (hereafter referred to as “1960 Hearing”), 14–19.

3. “Senate Unit Votes $4.5 million to Buy 1 1/2 Blocks Near ‘Hill’ Area,” Washington Post and Times Herald, February 9, 1956; 1960 Hearing, 25; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia, S. Rep. 57-166, 57th Cong., 1st sess., 1902, 37–40; Quinn Evans, Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument: Historic Resource Study, National Park Service (Jan. 2021): 3–51; Enlarging of the Capitol Grounds: The Final Report of the Commission for Enlarging of the Capitol Grounds, S.Doc 76-251, 76th Cong., 3rd sess., 1943, 493.

4. 1956 Hearings, 6; House Committee on Election of President, Vice President, and Representatives in Congress, Woman Suffrage: Hearings on H.R.26950, 62nd Cong., 3rd sess., January 31, 1913; Ross Richard Rice, Carl Hayden: Builder of the American West (University of Michigan, 1994), 46.

5. 1956 Hearings, 34, 54–57; Wes Barthelmes, “Capitol Grounds Expansion Opposed,” Washington Post and Times Herald, May 22, 1956.

6. Paul Sampson, “New Belmont House War,” Washington Post and Times Herald, February 19, 1957; Richard L. Lyons, “Belmont House Women in Arms,” Washington Post and Times Herald, March 29, 1957; “$965,000 Voted in Parking Bill,” Washington Post and Times Herald, January 30, 1958; Congressional Record, 85th Cong., 2nd sess., July 17, 1958, 11943.

7. Senate Committee on Public Works, Authorizing for Extension of New Senate Office Building Site, S. Rep 90-735, 90th Cong., 1st sess., November 8, 1967.

8. Emma Guffey Miller and Alice Paul to Senator Everett Jordan, September 17, 1969; Emma Guffey Miller and Alice Paul to Hale Boggs, September 17, 1968; Emma Guffey Miller to John W. McCormach, September 24, 1968; Mary Birckhead and Alice Paul to Charles E. Bennett, September 26, 1968; Alice Paul to Emma Guffey Miller, September 26, 1968, NWP Papers, Part 1, Section C: 1945–1974 (Sep. 1 – Sep. 30, 1968); "An Act to Authorize the Extension of the Additional Senate Office Building Site,” S.2484 90th Cong., 2nd sess., 1967; “Senate Office Building,” CQ Almanac 1968 24 (1969); ”One House Saves Another,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1968; ”Delay in Belmont House Bill,” Los Angeles Times, September 24, 1968; ”Senate Plan Brings Ringing Protests,” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1968.

9. James Banks to Elizabeth Chittick, July 16, 1973, NWP Papers, Part 1, Section C: 1945–1974 (Jul. 1 – Jul. 31, 1973); Suzanne Ganschinietz, National Register of Historic Places nomination: Sewell-Belmont House, Washington, D.C., June 16, 1972.

10. “Frankie Sue Del Papa,” Nevada Women’s History Project, accessed March 14, 2025, https://nevadawomen.org/del-papa-frankie-sue/.

11. Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Sewall-Belmont House National Historic Site, Hearing on S.3188, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., May 31, 1974, 73.

12. An Act to provide for the establishment of the Clara Barton National Historic Site, Maryland; John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon; Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota; Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Massachusetts; Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama; and Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, New York; and for other purposes, Public Law 93-486, 93rd Cong., 2nd. Sess., October 26, 1974, 88 Stat. 1463; Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Report on Providing for the Establishment of Clara Barton National Historic Site, Md., and Other Historic Sites and Memorials, S. Rep. 93-1233, 93rd Cong., 2nd. sess., October 4, 1974; Senate Committee on Public Works, Addition to the Dirksen Senate Office Building, Hearing, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., 1974, 49; Congressional Record, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., October 8, 1974, 34297–401; Wauhillau LaHay, “She’s the Happiest Woman in Washington,” NWP Papers, Group II: Printed Matter, 1850–1974.

13. Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Hearing on S.3188, 18; Dorothy McCardle, “Sen. Jackson Seeks Shrine for Women's Rights Movement,” Washington Post, April 14, 1974.

|

| 202412 16When is a Senate First Truly a First?

December 16, 2024

In May 1971, newspapers heralded the end of a “boys-only” Senate page tradition with the appointment of three female pages. Senate historians have recently learned, however, that the Senate employed female pages at least as early as 1907. Emma Madeen served as a Senate riding page from June to December of that year, one of eight female riding pages who served between 1907 and 1926. The “discovery” of female riding pages in the early 20th century prompts a question: In an institution as old as the Senate, how can historians be certain that any event is a Senate “first”?

In May 1971 newspapers heralded the end of a long tradition when the Senate approved a resolution to allow the appointment of three female pages: Paulette Desell, Ellen McConnell, and Julie Price. “New Pages in Senate’s History: Girls,” announced the Washington Post. “Senate pages have always been boys, altho [sic] there is no regulation against the appointment of girls,” reported the Chicago Tribune.1

On one hand, the Tribune was correct. There had never been a rule prohibiting the appointment of female pages in the Senate. On the other hand, the story inaccurately identified Desell, McConnell, and Price as the first female Senate page appointments. While the efforts of these three teenagers who successfully petitioned for their appointments were historically significant at the time, Senate historians have recently learned that the Senate appointed female pages at least as early as 1907. Emma Madeen served as a Senate riding page from June to December of that year, one of eight female riding pages who served between 1907 and 1926. The “discovery” of female riding pages in the early 20th century prompts a question: In an institution as old as the Senate, how can historians be certain that any event is a Senate “first”?

The appointment of Senate pages is one of the Senate’s oldest traditions. It began in 1824 when 12-year-old James Tims, the relative of Senate employees, was listed in the compensation ledger as “boy—for attendance in the Senate room.” In 1837 Senate employment records showed the position of “page” to identify young messengers who provided support for Senate operations. The titles and responsibilities of pages evolved with the institution. There were “mail boys” who helped with mail delivery, “telegraph pages” who delivered outgoing messages between the Capitol’s telegraph offices, “telephone pages” who received telephone messages, and “riding pages” who carried messages from the Senate to executive departments and the White House on horseback.

Though it is difficult to pinpoint the precise date of the Senate’s first riding page appointment, Senate records indicate that they served during the Civil War. An 1862 Senate expense report includes payment for the rental of two saddle horses and two letter bags for use by “riding pages.” During the war, riding pages delivered messages throughout Washington on horseback, a fast and relatively safe way to navigate a city pockmarked by open sewers, crisscrossed by muddy roads, and infiltrated by Confederate spies. The position continued long after the war. In 1880 Senate ledgers recorded back pay for riding page Andrew F. Slade, the first known African American page to serve in the Senate, and the title of “riding page” was listed on the secretary of the Senate’s report of expenses that year.2

By the late 1880s, riding pages did not rely solely on horses to navigate the city. The Senate appointed Carl A. Loeffler in 1889 as a riding page under the patronage of Senator Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania. When he arrived at the Senate, Loeffler learned that riding pages had recently experimented with using the city’s horse car system to deliver their messages. Horse-drawn trolley cars, or “horse cars,” were a popular mode of transportation in the 1880s, with systems in many large American cities, including New York, Boston, and Washington, DC. Horse cars allowed passengers to avoid walking on crowded and sometimes muddy streets. But riding pages needed to quickly deliver messages throughout the city’s federal departments and return promptly to the Capitol, and horse cars, which made frequent stops, proved to be an impractical option. By the 1890s, riding pages had largely abandoned the use of horse cars and, with Senate permission, adopted bicycles—the latest transportation innovation. However, Senate pages continued to deliver messages and packages on horseback through the 1910s, likely until the Senate formally closed its horse stables in 1914, as recorded in the secretary of the Senate’s annual report that year. The duties of the Senate riding pages have evolved alongside the Senate’s own evolving roles and responsibilities. By the 1950s, riding pages delivered messages to executive agencies by car, for example, making the position best suited for adult Senate staff. And while the role of the riding page has continued into the 21st century, modern Senate riding pages have not been a part of the Senate’s formal page program.3

Senate riding pages enjoyed many perks. In 1899 the annual salary for a riding page was $912.50, a considerable sum when compared with the salary of a Senate document folder ($840), or a laborer ($720). In addition to good pay, these teenagers also traveled about the city independently, escaping the watchful eyes of supervising adults for extended periods of time. Occasionally, when a favorite Senate Chamber page aged out of that program (in the early 20th century, 12- to 16-year-olds were eligible for the position), they transitioned to the riding page program.4

Much of what we know about the riding page position comes from one of the Senate’s many official records, the secretary of the Senate’s report of expenses, published annually (and later biannually). This report provides historians with a snapshot of the Senate community at a moment in time. The 1896 report, for example, includes all purchases and salaries paid that year, including one oak rocker for the Committee on Claims ($5.50), and a salary of $1,440 paid to S. F. Tappau for service as a messenger to that committee. That same year, the report documents salaries for four riding pages: M. S. Railey, J. A. Thompson, C. A. Loeffler, and Frank Beall. These detailed reports include the names of staff, their titles, and salaries, but do not categorize individuals according to race, ethnicity, or gender. To identify women on Senate staff, historians rely upon other clues, especially “gendered” first names, and turn to other sources, including census records, personal diaries, and newspaper accounts, in hopes of confirming personal details. As the 1896 report suggests, lists of names can be ambiguous when initials, rather than full names, are published. Additionally, feminine names can be difficult to trace through the years. When women marry, they often take their spouse’s surname, complicating efforts to document their full Senate employment record.5

Yet, even with these incomplete records, Senate historians can challenge some long-standing accounts of notable Senate “firsts.” During the summer of 1907, according to the secretary of the Senate’s report, the Senate employed four riding pages: F. Beall , Parker Trent, Albertus Brown, and E. Madeen. A subsequent report reveals that the initial E stands for “Emma.” Madeen may have been the first female page appointment, but no newspapers reported Madeen’s appointment as extraordinary at the time. Unfortunately, no official records provide historians with clues about Madeen’s life in the Senate, on Capitol Hill, or in Washington, DC. How old was she and how did she secure this job? In late December 1907, Helen Taylor replaced Madeen as a riding page. A year later, Taylor was joined by a second female page, Rose Baringer, and others followed. In addition to Madeen, Taylor, and Baringer, Flora White, Henrietta Greeley, Lucy Murphy, Mildred Larrazolo, and Marguerite Frydell served as Senate riding pages between 1907 and 1926.6

Senators and staff in 1971 may be forgiven for forgetting these female riding pages, who left the Senate 45 years before the Senate reportedly ended the “boys only” page tradition. But even this timeline is more complicated than it seems. From 1951 to 1954, both party cloakrooms employed women as their “chief telephone pages.” Operating out of the private spaces reserved for senators at the rear of the chamber, these women (census records indicate that they were likely adults, rather than girls or teens) answered incoming calls from staff in the Senate office building and provided critical updates about members’ whereabouts and the day’s scheduled floor proceedings and debates. Before technology allowed for the internal broadcasting of floor speeches over so-called “squawk boxes,” the Senate’s telephone pages helped to ensure the institution’s smooth operations and, as a constant presence in the cloakrooms, were likely recognizable. In 1971, when the Senate reportedly ended its “boys only” tradition, at least a dozen senators who voted on that proposal had served in the Senate from 1951 to 1954—when they had likely encountered these female telephone pages.7

Was Emma Madeen the first female page appointment? The answer may be yes—that is, until Senate historians find evidence of an earlier one!

Notes

1. Angela Terrell, “Girl Pages Approved,” Washington Post, May 14, 1971; “Fight for Senate Girl Pages,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1971.

2. J. D. Dickey, Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, D.C. (Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2014); “General of the Army: The Bill Passes Restoring the Title,” Atlanta Constitution, June 2, 1888.

3. Carl Loeffler unpublished memoir, Senate Historical Office files; John H. White, Jr., Horsecars, Cable Cars and Omnibuses (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1974); Senate Committee on Government Operations, “Special Senate Investigation on Charges and Countercharges Involving: Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens, John G. Adams, H. Struve Hensel and Senator Joe McCarthy, Roy M. Cohn, and Francis P. Carr, Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations,” 83rd Cong., 2nd sess., Part 1, March 16 and April 22, 1954, 35; “Security Minded CIA is so Secure Senator Can’t Get Letter to Director, Page Turned Back at Barricade,” Washington Post, June 11, 1963.

4. “California Boy Coolidge’s Page,” Boston Daily Globe, February 13, 1922.

5. Annual Report of William R. Cox, Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 55-1, 55th Cong., 2nd sess., December 6, 1897, 7–8.

6. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 60-1, 60th Cong., 1st sess., December 4, 1907, 26.

7. “Robert G. Baker: Senate Page and Chief Telephone Page, 1943–1953; Secretary for the Majority, 1953–1963,” Oral History Interviews, June 1, 2009, to May 4, 2010, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C., 14–15.

|

| 202403 15Women of the Senate Oral History Project

March 15, 2024

In honor of Women’s History Month, the Senate Historical Office introduces two oral history interviews in the Women of the Senate collection, Senators Barbara Boxer of California and Olympia Snowe of Maine. The Women of the Senate Oral History Collection documents women’s impact on the institution and its legislative business.

In honor of Women’s History Month, the Senate Historical Office introduces two new oral history interviews in the Women of the Senate collection, Senators Barbara Boxer of California and Olympia Snowe of Maine. The Women of the Senate Oral History Collection documents women’s impact on the institution and its legislative business.

Since 1976 the Senate Historical Office has conducted interviews with senators and staff. The mission of this project is to document and preserve the individual histories of a diverse group of personalities who witnessed events firsthand and offer a personal perspective on Senate history.

Just 60 women have served in the Senate since the first woman took the oath of office in 1922. By recording and preserving the stories of the Women of the Senate, we hope to develop a fuller, richer understanding of women’s role in the Senate and in governing the nation. From the role models who inspired them, to their decision to run for office, to their bonds with other senators, the stories of women in the Senate are central to understanding Senate history.

Barbara Boxer served in the United States Senate from 1993 to 2017 as a Democrat representing the State of California. Her opposition to the Vietnam War drew her to politics, and in 1976 she won her first election to public office, serving on the Marin County Board of Supervisors. She later served five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1983–1993), and in 1992 she won a seat in the U.S. Senate, joining Dianne Feinstein as the first women elected to the Senate from the State of California. In the Senate, Boxer championed international peace, equal rights and equal pay for women, and advocated for wildlife protections and environmental conservation. From 2007 to 2015, Boxer chaired two Senate committees, the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, and the Select Committee on Ethics—the first woman to lead each of those committees. She authored clean water legislation, pushed for legislation to address climate change, and shepherded bipartisan infrastructure bills through the Senate. In this interview, she discusses how the Senate’s design encourages bipartisanship, the value of having diverse viewpoints in the Senate, and the importance of having a thick skin while serving in public office.

Maine Republican Olympia Snowe won a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1994 after serving eight terms in the House of Representatives. During her three Senate terms (1995–2013), she became the first woman to chair the Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship and also served on the Committees on Armed Services, Commerce, Science and Transportation, and Foreign Relations. She worked to build bipartisan support for a number of legislative initiatives, including expanding health care access, balancing budgets, and addressing sexual harassment in the military.

In this interview, Snowe describes her early role models and meeting Maine’s first woman senator, trailblazer Margaret Chase Smith (1949–1973). Snowe considered herself a pragmatic lawmaker with a passion and penchant for public service. She discusses the differences between serving in the House and Senate, the role of women in lawmaking, the importance of the Senate’s bipartisan women’s monthly dinners, and the significance of placing the Portrait Monument (a statue dedicated to women’s suffrage leaders) in the Capitol Rotunda. At times during her Senate career, Snowe took political positions that were at odds with her own party conference, and she explains how and why she defended those positions.

These interviews are just a sample of the voices collected by the Senate Historical Office as part of its Women of the Senate oral history project. In addition to the complete interview transcripts, the Historical Office presents select video and audio excerpts that help to define and articulate the transformative role of women in Senate history. This curated video highlights how these senators and staff understood their role in the Senate and presents their reflections on how the growing number of women in the Senate have at times subtly and at times directly shaped legislative agendas.

|

| 202303 08Enriching Senate Traditions: The First Women Guest Chaplains

March 08, 2023

The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857, and for more than 100 years, guest chaplains had all been men. That changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition.

The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. All Senate chaplains have been men of Christian denomination, although guest chaplains, some of whom have been women, have represented many of the world's major religious faiths.

The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857. That year, with many senators complaining that the position had become too politicized, the Senate chose not to elect a chaplain. Instead, senators invited guests from the Washington, D.C., area to serve as chaplain on a temporary basis. In 1859 the practice of electing a permanent chaplain resumed and has continued uninterrupted since that time, but the practice of inviting a guest chaplain to occasionally open a daily session also continued. While it is possible, and perhaps likely, that the Senate selected guest chaplains prior to 1857, surviving records from the period are insufficient to make that determination.

By the mid-20th century, guest chaplains were frequently offering the Senate’s opening prayer. Clergy visiting the nation’s capital often communicated their desire to serve as a guest chaplain to their home state senators who would nominate them for the role. In the 1950s, this practice became so popular among senators that Chaplain Frederick Brown Harris, who served nearly 25 years as Senate chaplain, complained to Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas that guest chaplains had replaced him 17 times over the course of just a few weeks. Leader Johnson assured Harris that he would ask senators “to restrict the number of visiting preachers,” but the frequency of the guests persisted.1

During the 1960s, Harris suffered from a series of medical issues and was less engaged in his official duties. Consequently, Harris’s unplanned absences prompted new problems for the Senate majority leader, now Mike Mansfield of Montana, whose staff was forced to arrange for last-minute guest chaplains. Infrequently, they called on senators to offer the prayer. Further irritating the majority leader, Harris unwittingly hosted guest chaplains who used the “forum to present their own particular litanies” and political viewpoints, thereby violating the Office of the Chaplain’s tradition of nonpartisan, nonpolitical service.2

Such issues prompted Senate leaders to reevaluate policies related to the appointment of guest chaplains. When Reverend Harris passed away in early 1969, Majority Leader Mansfield and Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois created an informal, bipartisan committee on the “State of the Senate Chaplain.” Upon concluding their study, the leaders informed Harris’s successor, Chaplain Edward L. R. Elson, of a policy change: “It would be our judgement that under ordinary circumstances a regular practice of inviting two guest chaplains per month is now in order.” Also, “In instances when you are ill or unavoidably absent, we would expect you to ask a brother clergyman to fill in temporarily in your stead.” The new policy was intended to standardize and bring order to the guest chaplain practice.3

For more than 100 years, guest chaplains had been men, but that changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition. A 1942 graduate of the Union Theological Seminary, Rowland became a minister in 1957, after the Presbyterian Church allowed for the ordination of women. She was an author and associate minister in Cincinnati, Ohio, before joining the United Presbyterian Board of Christian Education in Philadelphia, where she directed its educational loans and scholarships program. When Chaplain Elson invited her to lead the Senate’s opening prayer, Rowland recognized the historical significance of his offer. “It’s an honor to pray with and for such an august body,” she explained to the press. “I’m not unmindful of the women’s lib[eration] angle to my performance. But the prayer, like any other I have offered, is still to God. I’ve kept that in mind while I’ve been working on it.”4

Generally, the opening of the Senate’s daily session is sparsely attended. Six senators were present in the Chamber on July 8, 1971, for this historic event, including the Senate’s only woman senator, Margaret Chase Smith of Maine. Senate President pro tempore Allen Ellender of Louisiana called the Senate to order at noon, then introduced Dr. Rowland as “the very first lady ever to lead the Senate in prayer.” Rowland began:

O God, who daily bears the burden of our life, we pray for humility as well as forgiveness. As our nation plays its part in the life of the world, help us to know that all wisdom does not reside in us, and that other nations have the right to differ with us as to what is best for them.

Rowland later reflected on the event: “I’m pleased not for myself but for the fact the Senate has reached the point where they feel it is normal to invite a woman to do this.”5

But it wasn’t normal yet, and three years would pass before another woman delivered the Senate’s opening prayer. On July 17, 1974, Sister Joan Doyle, president of the Congregation of Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary headquartered in Dubuque, Iowa, became the second woman and the first Roman Catholic nun to offer the opening prayer in the Chamber. Her sponsor, Iowa senator Dick Clark, introduced her. At the conclusion of Doyle’s prayer, Minority Leader Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania praised her “gentler touch” for preparing senators to enter “into the brutal conflicts of the day.” Senator Margaret Chase Smith had retired in 1973, and Senator Clark reflected on the lack of women senators in the Chamber that day. “I hope it won’t be three more years before another woman is here, not only for the opening prayer, but as a member of the Senate.” It took more than five years, in fact, for the next woman senator to take a seat in the Chamber. On January 25, 1978, Muriel Humphrey was appointed to fill the seat left vacant when her husband, Senator Hubert Humphrey, passed away.6

Since 1974 other women have followed in the footsteps of Reverend Rowland and Sister Doyle, although the number of female guest chaplains remains small. In 2008 the Reverend Dr. Patricia Bryant Harris made history as the first African American woman to give the Senate’s opening prayer. “It had a lot of meaning to me personally, to be a part of that history,” Reverend Harris said in an interview. “That is now history as part of the Congressional Record.”7

The chaplain has been an integral part of the Senate community since the election of the first chaplain, Samuel Provoost, on April 25, 1789. Today, chaplains and guest chaplains, now men and women, deliver the opening prayer each day that the Senate is in session. As Senator Mary Landrieu of Louisiana remarked in 2012, "It is good that we take a moment before each legislative day begins in the Senate to still ourselves and ask for God's grace and guidance on the work that we have been called to do."8

Notes

1. Congressional Record, 91st Cong., 2nd sess., August 20, 1970, 29611.

2. “Chaplain Absent, Senator Gives Prayer,” Hartford Courant, September 20, 1963, 25B; “Senator Takes Chaplain’s Place,” Washington Post, Times Herald, September 2, 1964; Memorandum from Richard Baker to Mike Davidson, September 19, 1985, in the files of the Senate Historical Office.

3. Mike Mansfield and Everett Dirksen to Dr. Edward L. R. Elson, Chaplain, April 29, 1969, in the files of the Senate Historical Office.

4. “Barrier to Fall: Woman Will Lead the Senate in Prayer,” Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), July 4, 1971, A-10; “A Woman, Praying for the Senate,” Washington Post, July 9, 1971, B2.

5. Congressional Record, 92nd Cong., 1st sess., July 8, 1971, 23997; “Barrier to Fall: Woman Will Lead the Senate in Prayer.”

6. “Nun Gives Prayer in Senate,” Catholic Standard, July 25, 1974.

7. Nicole Gaudiano, “Del. Pastor makes history in U.S. Senate,” News Journal (Wilmington, DE), July 11, 2008, B1.

8. “At Sen. Landrieu’s Invitation, Louisiana Chaplain Offers Opening Prayer for U.S. Senate,” Targeted News Service, Feb. 28, 2012.

|

| 202302 02The Power of a Single Voice: Carol Moseley Braun Persuades the Senate to Reject a Confederate Symbol

February 02, 2023

On July 22, 1993, senators were considering amendments to a national service bill when suddenly, the Senate Chamber doors flew open and Illinois senator Carol Moseley Braun rushed to her desk and sought recognition. North Carolina senator Jesse Helms had proposed an amendment to renew a patent to the United Daughters of the Confederacy for an insignia that featured the first national flag of the Confederate States of America. Senator Moseley Braun, the first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, intended to stop that amendment.

July 22, 1993, began as an ordinary day as senators considered amendments to the National and Community Service Act of 1990. That routine business was suddenly interrupted, however, when the Senate Chamber doors flew open and Illinois senator Carol Moseley Braun, the first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, rushed to her desk and sought recognition from the presiding officer. Under consideration was an amendment introduced by North Carolina senator Jesse Helms to renew a patent to the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) for an insignia that featured the first national flag of the Confederate States of America.1

The UDC first obtained a congressional patent for its insignia in 1898. A small number of such patents had been granted to a group of organizations considered to be civic or patriotic, such as the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic and the American Legion. The patents expired after 14 years, unless renewed, and the UDC’s patent had been routinely renewed throughout the 20th century. The latest renewal effort had been considered in the Judiciary Committee and passed by the Senate in 1992, but it was left unfinished when the House of Representatives adjourned at the end of the session. In the spring of 1993, South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond again raised the patent issue in committee, expecting easy approval, but the composition of the committee had changed. In the wake of the 1992 election, labeled the “Year of the Woman” by the press, two women now sat on the Judiciary Committee, including Illinois freshman Carol Moseley Braun.2

On May 6, 1993, the patent renewal came before the committee for a vote. Moseley Braun looked at it and said, “I am not going to vote for that.” Challenging Thurmond and his allies, Mosely Braun stated that she did not oppose the existence of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, nor did she object to their ability to use the flag. If the UDC sought a congressional imprimatur for that insignia, however, Moseley Braun insisted that “those of us whose ancestors fought on a different side of the conflict or were held as human chattel under the flag of the Confederacy have no choice but to honor our ancestors by asking whether such action is appropriate.” Moseley Braun proved to be persuasive, and the committee voted 12 to 3 against renewal. She thought the debate had ended, but when Senator Helms appeared in the Chamber on July 22 to seek approval of an amendment that would renew the UDC patent, the battle began again.3

“Mr. President,” Helms began, “the pending amendment … has to do with an action taken by the Senate Judiciary Committee on May 6…. This action was, I am sure, an unintended rebuke unfairly aimed at about 24,000 ladies who belong to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, most of them elderly, all of them gentle souls.” Briefly summarizing the many charitable efforts of the UDC, Helms noted that since 1898, “Congress has granted patent protection for the identifying insignia and badges of various patriotic organizations,” including the UDC. Renewing the patent, he insisted, was not an effort “to refight battles long since lost, but to preserve the memory of courageous men who fought and died for the cause they believed in.”4

Sitting in a committee hearing, Moseley Braun was surprised to hear of Helms’s efforts on behalf of the UDC. She rushed to the mostly empty Chamber—only three senators had been present when Helms introduced his amendment—and began an impromptu speech. Stating that Helms was attempting to undo the work of the Judiciary Committee, Moseley Braun again laid out her objections. “To give a design patent,” a rare honor “that even our own flag does not enjoy, to a symbol of the Confederacy,” she argued, “seems to me just to create the kind of divisions in our society that are counterproductive…. Symbols are important. They speak volumes.” Helms, Thurmond, and their allies dismissed her objections, noting the important work done by the UDC, especially the organization’s aid to veterans of all wars, but Moseley Braun refused to back down. “It seems to me the time has long passed when we could put behind us the debates and arguments that have raged since the Civil War, that we get beyond the separateness and we get beyond the divisions.” Thinking she had put forth a convincing argument, Moseley Braun introduced a motion to table the Helms amendment, which would effectively block its passage.5

As a vote was called on her motion to table the amendment, senators strolled into the Chamber for what they thought was a routine vote on an inconsequential issue. One senator later admitted that he “didn’t have the slightest idea what this was about.” As the roll call continued, it became clear that most senators were voting along party lines. With her party in the majority, Democrat Moseley Braun should have been well placed for success, but nearly all southern senators, regardless of party affiliation, supported Helms. The final tally was 48 to 52 against, and Moseley Braun’s motion to table the amendment went down to defeat.

Stunned, Moseley Braun again sought recognition. As she gained the floor a second time, her voice betrayed a sense of urgency. “I have to tell you this vote is about race,” she declared. “It is about racial symbols … and the single most painful episode in American History.” Earlier, she had “just kind of held forth and quietly thought [she] could defeat the motion,” Moseley Braun recalled in an oral history interview. When the motion was defeated, however, her reaction was, “Whoa! Wait a minute. This cannot be!” Insisting on holding the floor and yielding only for questions, Moseley Braun warned her colleagues, “If I have to stand here until this room freezes over, I am not going to see this amendment put on this legislation.”6

Realizing that many of her colleagues had cast their vote with little knowledge of the actual content of the amendment, Moseley Braun explained why she believed this vote was important. To those who thought the amendment was “no big deal,” she explained that this was “a very big deal indeed.” Approval of this Confederate symbol would send a signal “that the peculiar institution [of slavery] has not been put to bed for once and for all.” As Moseley Braun continued her unplanned filibuster, senators began to listen. Several commented that they hadn’t understood the full meaning of the amendment and regretted their vote. Nebraska senator James Exon summed it up: “The Senate has made a mistake.” But the motion to table had failed. What could be done?7

What followed was a dramatic turn of events. Over the course of a three-hour debate, senators began calling for reconsideration of Moseley Braun’s motion. The pivotal moment came when Alabama senator Howell Heflin took the floor. “I rise with a conflict that is deeply rooted in many aspects of controversy,” he began. “I come from a family background that is deeply rooted in the Confederacy.” Heflin spoke of his deep respect for his ancestors and for the charitable work of the Daughters of the Confederacy, but he acknowledged the changing times. “The whole matter boils down to what Senator Moseley Braun contends,” he concluded, “that it is an issue of symbolism. We must get racism behind us, and we must move forward. Therefore, I will support a reconsideration of this motion.” With Heflin leading the way, others followed.8

Introduced by Senator Robert Bennett of Utah, a motion to reconsider gave senators a second chance to vote. When the roll call ended, 76 senators supported Moseley Braun. She had convinced 28 senators, including 10 from formerly Confederate states, to change their vote. With that motion passed, Moseley Braun’s motion to table the amendment again came before the Senate, passing by a vote of 75 to 25. Helms’s amendment was tabled and did not appear in the bill. Moseley Braun thanked her colleagues “for having the heart, having the intellect, having the mind and the will to turn around what, in [her] mind, would have been a tragic mistake.”9

Rare are the moments in Senate history when a single senator has changed the course of a vote. In this case, the presence of an African American woman, who was the only Black member of the Senate, altered the debate. That fact was readily acknowledged. “If ever there was proof of the value of diversity,” commented California senator Barbara Boxer, “we have it here today.” Ohio senator Howard Metzenbaum agreed. “I saw one person, who was able to make a difference, stand up and fight for what she believes in” and “she showed us today how one person can change the position of this body.” 10

Notes

1. “On Race, a Freshman Takes the Helm,” Boston Globe, July 25, 1993, 69.

2. “Confederate Flag Raises Senate Flap,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 6, 1933, 1A; “A Symbolic Victory for Moseley-Braun,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1933, D3; “Confederate Symbol Causes Controversy,” New York Times, May 10, 1993, D2; “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate,” New York Times, July 23, 1993, B6. The insignia was last renewed on November 11, 1977, by Public Law 95-168 (95th Cong.).

3. Congressional Record, 103rd Cong., 1st sess., July 22, 1993, 16682; “Moseley-Braun opposes Confederate Group on Insignia,” Chicago Tribune, May 4, 1933, D7; “Daughters of Confederacy’s Insignia Divides Senate Judiciary Committee,” Wall Street Journal, May 6, 1933, A12; “Braun Leads Fight Against Confederate Logo,” Chicago Defender, May 11, 1933, 8.

4. Congressional Record, 16676. The Record reflects Helms’s slight revisions to his statement.

5. Congressional Record, 16678, 16681.

6. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; “Freshman Turns Senate Scarlet,” Washington Post, July 27, 1993, A2; "Carol Moseley Braun: U.S. Senator, 1993–1999," Oral History Interviews, January 27 to June 16, 1999, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C., 18; Congressional Record, 16681, 16683.

7. Congressional Record, 16683, 16684.

8. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; Congressional Record, 16687–88.

9. Congressional Record, 16693–94.

10. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; “Moseley-Braun Molds Senate’s Outlook on Racism,” Austin American Statesman, July 24, 1993, A17; Congressional Record, 16691.

|

| 202211 21Rebecca Felton and One Hundred Years of Women Senators

November 21, 2022

On November 21, 1922, Rebecca Felton of Georgia took the oath of office, becoming the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate. Though her legacy has been tarnished by her racism, the significance of this milestone—now 100 years old—remains. Felton’s historic appointment opened the door for other women senators to follow. One hundred years later, 59 women have been elected or appointed to the Senate, and many more women have supported Senate operations as elected officers and staff.

On November 21, 1922, Rebecca Felton of Georgia took the oath of office, becoming the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate. Though her legacy has been tarnished by her racism, the significance of this milestone—now 100 years old—remains. Felton’s historic appointment opened the door for other women senators to follow. One hundred years later, 59 women have been elected or appointed to the Senate, and many more women have supported Senate operations as elected officers and staff.

Appointed to fill a vacant seat on October 3, 1922, Felton formally took the oath of office in the Senate Chamber on November 21 and served only 24 hours while the Senate was in session. For Felton, that historic day marked the culmination of a lifetime of political activism as a feminist, journalist, and suffragist. Like many of her contemporaries, however, Felton was also a white supremacist whose views on race both reflected and reinforced racial inequality for generations. Her complicated legacy sheds light on both the progressive and the reactionary politics that she influenced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born Rebecca Latimer in 1835, she was the daughter of a wealthy Georgia planter. She married Dr. William Felton in 1853, moving to his home near Cartersville. Although the state of Georgia prohibited women from owning property at that time, as the mistress of her husband’s plantation, Felton managed a household that included 50 enslaved people.

In 1860, as Civil War approached, the Feltons initially opposed the secession of Southern states from the Union, but like other white Southerners of their social class, they supported the Confederacy during the war to protect their “ownership of African slaves.” Felton later explained, “All I owned was invested in slaves.” She joined the local Ladies Aid Society to support the Confederate army. A physician and a preacher, William Felton tended Confederate soldiers at a nearby military camp, frequently leaving Rebecca alone to defend their property. Physical assault by marauding soldiers was a common wartime experience for rural women like Felton, and their trauma informed Felton’s political advocacy as she later fought for financial security and protection from sexual violence for all women.1

When the war concluded, the Feltons were emotionally depressed and financially destitute. They lost their farm and livelihood during the war and suffered the loss of two young children to wartime diseases. They founded a school, but politics soon came calling. After a report of the brutal sexual assault of a Black girl in a chain gang, Rebecca petitioned the Georgia state legislature to enhance protections for all female labor convicts—Black and white—and she would fight for prison reform for the remainder of her life. William pursued electoral politics, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Georgia state legislature. Felton participated in all aspects of her husband’s career, serving as his campaign manager and speechwriter, atypical roles for a woman in the 19th century. Political opponents criticized their unusual partnership. “We sincerely trust that the example set by Mrs. Felton will not be followed by southern ladies,” complained the Thomasville Times. “Let the dirty work in politics be confined to men.” By serving as her husband’s partner, and at times as his political surrogate, Felton helped to redefine the “traditional” role of southern white women.2

In the 1880s, Rebecca Felton broadened her activism, joining the temperance movement and emerging as a prominent and dynamic public speaker for the rights of poor, rural white women. A prolific and engaging writer, she co-founded a small newspaper in 1885 and later wrote a semi-weekly column for the Atlanta Journal. By the 1890s, Felton had emerged as a prominent public figure whose rousing speeches drew large crowds and whose columns and letters to the editor were widely distributed and debated nationwide. Felton used her influence to push for progressive policy reforms on behalf of white women and children, including universal public education, prison reform, better employment opportunities for women, and female suffrage.3

Felton’s views on race, however, were far from progressive, and throughout her life she held and perpetuated racist attitudes about African Americans. Decades after the Civil War, she continued to promote the myth of the happy enslaved person. She dehumanized Black men, calling them “debased, lustful brutes.” In her memoirs, published in 1919, Felton acknowledged that white supremacy served as an organizing principle for white southerners during and after the war. “The dread of negro insurrection and social equality with negroes at the ballot box held the Southern whites together in war or peace.” By the 1890s, many former Confederate states had adopted new constitutions to restrict African Americans’ civil rights, particularly voting rights. Prominent political figures, including Felton, inflamed racial tensions by promoting unfounded allegations of Black men assaulting white women. Such allegations fueled the heinous practice of lynching.4

In a widely reported speech in 1897, Felton criticized white men for their indifference to women’s rights and their failure to protect white women from assault, promoting her vision of equality for farm women. In the final moments of the speech, however, she pivoted to reactionary race politics: “As long as your politicians take the colored man into their embrace on election day…so long will lynching prevail.…If it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts,” she said, “then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary.” Although the purpose of her speech had been to promote the empowerment of white rural women, in the weeks and months that followed, it was Felton’s virulent support for lynching that was widely reported and used as justification for this barbaric practice.5

Shortly after her husband’s death in 1909, Felton joined the suffrage movement and canvassed the state to promote voting rights for women. Racism played a prominent role here as well, with many leading white suffragists insisting that extending voting rights to white women would help to dilute the voting power of Black men. When Felton testified before the all-male Georgia state legislature in 1914, for example, she asked: “Why can’t [women] help you make the laws the same as they help you run your homes and churches? I do not want to see a negro man walk to the polls and vote … while I myself [cannot].” In 1920 Felton and fellow suffragists celebrated the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which extended voting rights to many, though not all, women. Her suffrage work enhanced her popularity among newly enfranchised women voters in Georgia and beyond.6

In September 1922, when Georgia senator Thomas Watson died in office, he left a vacancy to be filled by gubernatorial appointment until the upcoming special election. Georgia governor (and former senator) Thomas Hardwick planned to appoint a “place-holder” and then run for that seat himself. Because he had opposed the Nineteenth Amendment, Hardwick feared newly enfranchised women would deny him the coveted Senate seat. On October 3, 1922, hoping to quell their opposition, Hardwick chose 87-year old Rebecca Latimer Felton of Cartersville for the historic appointment.

Hardwick ceremonially presented Felton with her appointment at Bartow County Courthouse on October 6. Women packed the courthouse, eager to show their support for the first woman senator. Because the Senate had adjourned sine die until December, and her replacement would be elected on November 7, Hardwick’s action was viewed as a symbolic attempt to gain women’s votes. Though Felton would receive a Senate salary and the administrative support of a secretary, as one newspaper reported, it was “only remotely possible” that she would appear on the Senate floor.7

Not content with a remote possibility, Felton’s allies launched an effort to have her seated in the Senate. Helen Longstreet, the widow of Georgia’s Confederate general James Longstreet, petitioned President Warren G. Harding in person on October 5, requesting that he call a special session before the November election so that Felton could be sworn in. Others followed Longstreet’s lead. “I voice the desire of multitudes of women voters,” explained one prominent suffragist in a letter to Harding, “who will shortly be approaching the polls.” Harding ignored the political pressure for a time, resisting calls for a special session. Meanwhile, on October 17, Governor Hardwick lost the Democratic primary to Judge Walter George, who won the general election on November 7. Felton now had an elected successor, but that didn’t halt the pressure to provide her the opportunity to take a Senate seat. Felton lobbied Harding to call Congress back for a special session as many of her supporters petitioned the president for action. On November 9, the president relented, announcing a special session to begin November 20 to consider several Republican legislative priorities. Attention again turned to Felton. Would she be seated?8

Less than a week before the special session was scheduled to convene, Georgia secretary of state S. G. McLendon, Felton’s political ally, declared that Walter George’s election likely would not be certified before the special session began. The ballots of 14 Georgia counties remained to be counted, he explained, and the state canvassing board had yet to be called to certify those results. According to state law, only the governor had the authority to convene the canvassing board, and Governor Hardwick was vacationing in New York. To resolve the situation, Hardwick returned to Georgia and convened the board, which promptly certified the election results. When the Senate convened on November 20, Senator-elect Walter George would be certified and ready to present his credentials. To many, Felton’s chances of taking the oath of office in an open session seemed to be dwindling.9

Undeterred, Felton personally asked George to delay presenting his credentials to the Senate. “I have no objections to interpose,” George astutely proclaimed at a press conference after their meeting. “The Senate is the exclusive judge of the eligibility of its members.… I will be glad to see the distinction come to [Felton], if the Senate can and will find a way to make this legally possible.” After George’s public announcement, Felton’s goal seemed within reach. She packed her bags and boarded a train to Washington, D.C. Both she and George would be present when the Senate convened for the special session. The Senate would decide her fate.10

On Monday, November 20, Felton arrived at the Senate early, her credentials tucked under her arm. Escorted into the Chamber by former Georgia senator Hoke Smith, she took a seat at an empty desk. Senators surrounded her, extending her a warm welcome. When the Senate convened at noon, it approved a resolution recognizing the death of her predecessor Thomas Watson and then—as was Senate custom—adjourned for the day. The question of Felton taking the oath would have to wait another 24 hours.

Felton again arrived early on November 21 and received a raucous ovation from visitors in the galleries as she took a seat at Watson’s vacant desk. After recessing for a joint session, the Senate reconvened, accepted the credentials of two new members, and then turned to deciding Felton’s case. Thomas Walsh of Montana addressed the chair. First describing the law that seemed to prevent Felton from being seated, Walsh then provided precedents in her favor. “I did not like to have it appear, if the lady is sworn in—as I have no doubt she is entitled to be sworn in—that the Senate … extend[ed] so grave a right to her as a favor, or as a mere matter of courtesy, or being moved by a spirit of gallantry,” he said, “but rather that the Senate, being fully advised about it, decided that she was entitled to take the oath.” Without objection, the clerk proceeded to read the certificate as presented by Felton, and Vice President Calvin Coolidge administered the oath of office shortly after noon.11

As a duly sworn senator, Felton answered one roll call and delivered a single speech. "When the women of the country come in and sit with you,” she told her Senate colleagues, “...you will get ability, you will get integrity..., you will get exalted patriotism, and you will get unstinted usefulness." She served for 24 hours before relinquishing the seat to Senator-elect Walter George. A gallery full of women erupted into cheers and applause as Senator Felton bade farewell.12

Following her appointment, Felton had predicted that women’s era had dawned, but women’s time in the Senate had begun to dawn even before Felton’s historic appointment. The Senate had already benefitted from a small but talented group of pioneering female staff, including Leona Wells, who joined the Senate's clerical staff in 1901 and became one of the first women to serve as lead clerk on a committee. By the early 1920s, women held half of the Senate’s committee staff positions. Today, women hold many of the most important and influential posts in the Senate, including secretary of the Senate and sergeant at arms.13

As Felton predicted, however, her historic appointment did pave the way for other trailblazing women senators. Hattie Caraway of Arkansas became the first woman to win election to the Senate in 1932 and subsequently the first to chair a committee. In 1938 Senator Gladys Pyle of South Dakota became the first Republican woman to serve in the Senate. Margaret Chase Smith of Maine took the oath of office in 1949, becoming the first woman to serve in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois, having prevailed in the general election of 1992, was the first African American woman senator. In 1995 Barbara Mikulski of Maryland set a milestone by becoming the first woman elected to Democratic Party leadership, and in 2000 Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas achieved that goal for the Republican Party. Other milestones followed. In 2013 Mazie Hirono of Hawaii became the first Asian and Pacific Islander woman to take the oath, while Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin became the first openly gay senator. The first Latina, Catherine Cortez Masto, joined the Senate in 2017. When Vice President Kamala Harris took the oath of office in 2021, she became the first woman to serve as president of the Senate and the first Asian American and African American to hold that position. On November 5, 2022, Senator Dianne Feinstein of California became the longest serving woman senator, with more than 30 years of Senate service. To date, 59 women have followed the trail blazed by Felton in 1922, with 24 serving in the 117th Congress. While historians continue to reckon with the troubling aspects of Felton’s life and career, her legacy as the first woman senator remains a significant milestone—now 100 years old—in the history of the Senate.

Notes

1. Rebecca Latimer Felton, Country Life in Georgia in the Days of My Youth (Atlanta, GA: Index Printing Co., 1919), 80, 86; Crystal N. Feimster, Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 7–36.

2. John E. Talmadge, Rebecca Latimer Felton: Nine Stormy Decades (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1960), 79; Feimster, Southern Horrors, 34–35.

3. Talmadge, Rebecca Latimer Felton, 125; LeeAnn Whites, “Rebecca Latimer Felton and the Wife’s Farm: The Class and Racial Politics of Gender Reform,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 76, No. 2 (Summer 1992): 372.

4. Felton, Country Life in Georgia, 87; Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 197, 213; Rebecca Felton to the Editor, Boston Transcript, “Mrs. Felton Not for Lynching,” Atlanta Constitution, August 20, 1897, 4.

5. “Woman Advocates Lynching: Sensational Speech by the Wife of ex-Congressman Felton,” Washington Post, August 14, 1897, 6; Felton, Country Life in Georgia, 87; Feimster, Southern Horrors, 126–28, 133–35.

6. Feimster, Southern Horrors, 200–201.

7. “Commission Given Mrs. W.H. Felton by the Governor,” Atlanta Constitution, October 7, 1922, 3; Talmadge, Rebecca Latimer Felton, 140–42; “Mrs. W.H. Felton Named Senator; Hardwick in Race,” Atlanta Constitution, October 4, 1922, 1.

8. “Ask Special Session to Seat Senator Felton,” Baltimore Sun, October 13, 1922, 1.

9. Talmadge, Rebecca Latimer Felton, 143; “George’s Commission Held Up,” Baltimore Sun, November 16, 1922, 1; “George has time to be Qualified for Senate Seat,” Atlanta Constitution, November 18, 1922; 1.

10. “Judge W. F. George and Mrs. Felton to Confer Today,” Atlanta Constitution, November 17, 1922, 1.

11. “Senate to Decide Today on Seating Woman Senator,” Atlanta Constitution, November 21, 1922, 1; Congressional Record, 67th Cong., 3rd sess., November 21, 1922, 14.

12. Congressional Record, November 22, 1922, 23; “Mrs. Felton to Tax Senate Gallantry,” Baltimore Sun, November 19, 1922, 9.

13. “Women of the Senate,” United States Senate, accessed November 7, 2022, https://www.senate.gov/about/women-of-the-senate.htm

|

![Image: [Robert] Dole (Cat. no. 11.00129.096)](/about/resources/graphics/blog-cropped/11_00129_096.jpg) | 202206 01Picturing the Senate: The Works of Eleanor Mill and Lily Spandorf

June 01, 2022

In 2018 14 drawings by artist Eleanor Mill, featuring mostly senators and vice presidents, joined an important group of illustrations by the artist Lily Spandorf, expanding the Senate’s holdings of works by women artists. Bolstering the Senate’s extensive collection of works on paper, these illustrations demonstrate how these two women used their artistic talents to memorialize their perspectives on the Senate. Together, these collections showcase key events, buildings, and individuals that helped shape the Senate in the second half of the 20th century.

I love the humor you can get out of politics.1

So stated Eleanor Mill about her work as a political cartoonist and caricaturist. Fourteen of her drawings, all featuring the Senate, were donated to the Senate in 2018. The gift, which also included 84 works on paper by the artist Aurelius Battaglia, came from the artists’ daughter, Nicola Battaglia, in memory of her parents. Mill’s drawings represent the most recent addition of works by a contemporary woman artist to the Senate Collection. The drawings join an important group of 70 illustrations by the artist Lily Spandorf, expanding the Senate’s holdings of works by women artists. Together, these collections reflect a range of artistic techniques and showcase key events, buildings, and individuals that helped shape the Senate in the second half of the 20th century.

Eleanor Mill (1927–2008) was born in Michigan. Her father was an executive at General Motors, and the family relocated with such frequency that by the time she graduated from high school, she had attended 21 schools in 18 states. Eleanor trained at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., and married Aurelius Battaglia in 1948, although they would later separate. She enjoyed early success illustrating children’s books.

It was not until the middle of her career that Mill found her true calling: political cartooning. The artist reflected on this transformation in an interview she gave to the Hartford Courant in 1988: “I spent a lot of my life doing what other people told me to do, or what other people told me I was good at. I had to get older to realize I could do what I wanted. I love what I’m doing now.” In a second interview in 1992, she discussed how her art served as a form of advocacy: “I’ve always been political, I just never thought I could do anything about it in my work until I got old.” She was well aware how few women artists were creating political art and recalled how an art director at Life magazine once told her agent that “it would be a lot easier for [Mill] if [her] name were Edward.”2

Mill’s principal focus was people, often without dialogue or background, and her use of pen-and-ink was well suited to newspapers. Mill found that televised news could be one source of inspiration: “I also use my VCR to record people so I can draw them. I don’t like to rely too much on photographs. It’s better to see [people] in movement; you get more personality.”3

Mill self-syndicated her drawings through the Mill News Art Syndicate, and her work appeared, sometimes as illustrations for op-eds, in more than 40 national newspapers. Mill sought to connect readers with topical contemporary issues ranging from politics to homelessness. While she hoped that her drawings focusing on social issues might inspire viewers to action, she had a different intention for her political drawings: “Just make them laugh.”4

The Senate’s Eleanor Mill collection consists primarily of political cartoons and caricatures of senators and vice presidents that date from the 1980s to the early 2000s. Many of her caricatures, such as those of Albert A. Gore (D-TN) and Robert J. Dole (R-KS) emphasize certain facial features of her subjects, often for humorous effect. She sometimes departed from caricature to provide a more realistic portrayal, such as in a later drawing of Gore. Other caricatures, such as one referencing Dole’s 1996 presidential campaign, include additional detail to anchor the subject in the historical moment.

Lily Spandorf (1914–2000), a native of Austria, worked for the Washington Star as a contributing artist from 1960 to 1981, providing artistic interpretations of news subjects such as the 1968 Democratic National Convention and the White House Easter Egg Roll. Her work can be found in museum collections and in the book Lily Spandorf’s Washington Never More (1988), which showcases more than 70 of her paintings of Washington, D.C., neighborhoods and buildings. Spandorf preferred creating her work “on the spot” and often searched for outdoor locations in which to draw or paint.5

In 1961 the Washington Star assigned Spandorf to sketch scenes from the filming of Otto Preminger’s Advise and Consent , taking place on location on Capitol Hill. After completing the drawings for her initial assignment, she used her press pass over the next several weeks to continue sketching scenes from the filming. “It was exciting and I loved every bit of it,” she recalled in a 1999 interview. Her work caught Preminger’s attention, and at his request her drawings were displayed at the Washington premiere of the film.6

Spandorf worked in pen-and-ink and gouache (a water-based painting technique) to create these drawings, which include numerous views of the Capitol and the Russell Senate Office Building. In the drawing of the actor Don Murray in the Russell Building corridor and in one featuring a cameraman in the Russell Building stairwell (shown here), Spandorf documents the entire scene to impart as much information to the viewer as possible. The cast and crew are captured in a moment of filming, in backgrounds of bricked archways, grand stairwells, and marble arches. She developed friendships with the people on the set, and that intimacy is reflected in her portraits of individuals, such as that of the actor Charles Laughton.

The Advise and Consent drawings chronicle interactions between people and architecture, a hallmark of Spandorf’s work. “I combined the action on both sides of the camera with the setting of the U.S. Capitol and Washington. The images capture the events surrounding this unique filming—the only time the interior of the Capitol has been used as a movie set.” The work was challenging, but rewarding: “When I looked at them after years, I was amazed at myself. How could I do that? Because many times I had to be standing up somewhere in the corner to catch the people, and I got amazing likenesses.”7

The drawings by Eleanor Mill and Lily Spandorf bolster the Senate’s extensive collection of works on paper, which range from the 19th century to the present, and demonstrate how these two women used their artistic talents to memorialize their perspectives on the institution. Selections of drawings by both artists can be found by visiting the Art & Artifacts section of the Senate website.

Notes

1. Tom Condon, “Artist Vents Conscience in Cartoons,” Hartford Courant, October 15, 1988, D-1.

2. Condon, “Artist Vents Conscience”; Steve Kemper, “Eleanor Mill: ‘I see no reason to draw pretty pictures….The good things are not the things you need brought to your attention,’” Hartford Courant, September 20, 1992, 14.

3. Kemper, “Eleanor Mill.”

4. Condon, “Artist Vents Conscience.”

5. David Montgomery, “A Perennial Draw Pictures Washington: ‘On-the-Spot’ Art Preserves City’s Past,” Washington Post, December 28, 1998, B-1.