Welcome to Senate Stories, our new Senate history blog. In recognition of Black History Month, our first blog post celebrates the sesquicentennial of the swearing in of Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African American senator.

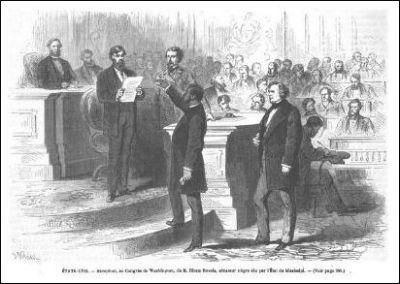

One hundred and fifty years ago, on February 25, 1870, visitors in the packed Senate galleries burst into applause as Senator-elect Hiram Revels, a Republican from Mississippi, entered the Chamber to take his oath of office. Those present knew that they were witnessing an event of great historical significance. Revels was about to become the first African American to serve in the United States Congress. Just 22 days earlier, on February 3, the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, prohibiting states from disenfranchising voters “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Revels was indeed “the Fifteenth Amendment in flesh and blood,” as his contemporary, the civil rights activist Wendell Phillips, dubbed him.

Hiram Revels was born a free man in Fayetteville, North Carolina, on September 27, 1827, the son of a Baptist preacher. As a youth, he took lessons at a private school run by an African American woman and eventually traveled north to further his education. He attended seminaries in Indiana and Ohio, becoming a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1845, and eventually studied theology at Knox College in Illinois. During the turbulent decade of the 1850s, Revels preached to free and enslaved men and women in various states while surreptitiously assisting fugitive slaves.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Revels was serving as a pastor in Baltimore. Before long, he was forming regiments of African American soldiers in Maryland, serving as a Union army chaplain in Mississippi, and establishing schools for freed slaves in Missouri. He settled in Natchez, Mississippi, at war’s end, where he served as presiding elder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1868 he gained his first elected position, as alderman for the town of Natchez. The next year he won election to the state senate, as one of 35 African Americans elected to the Mississippi state legislature that year.

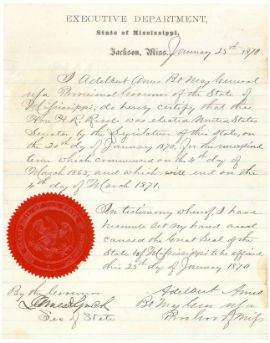

In 1870, as Mississippi sought readmission to representation in the U.S. Congress, the Republican Party firmly controlled both houses of Congress and also dominated the southern state legislatures. That, along with the pending ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, set the stage for the election of Congress’s first African American members. One of the first orders of business for the new Mississippi state legislature when it convened on January 11, 1870, was to fill the vacancies in the United States Senate, which had remained empty since the 1861 withdrawal of Albert Brown and future Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Representing around one-quarter of the state legislative body, the black legislators insisted that one of the vacancies be filled by a black member of the Republican Party. “An opportunity of electing a Republican to the United States Senate, to fill an unexpired term occurred,” Revels later recalled, “and the colored members after consulting together on the subject, agreed to give their influence and votes for one of their own race for that position, as it would in their judgement be a weakening blow against color line prejudice.” Since Revels had impressed his colleagues with an impassioned prayer at the opening of the session, legislators agreed that the shorter of the two terms, set to expire in March 1871, would go to him.

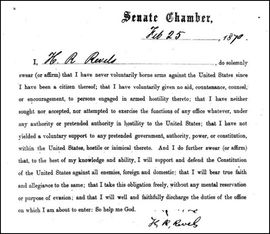

Mississippi gained readmission on February 23, 1870, and Senator Henry Wilson, one of the Senate’s strongest civil rights advocates, promptly presented Revels’s credentials to the Senate. Immediately, three senators issued a challenge. They charged that Revels had not been a U.S. citizen for the constitutionally required nine years. Citing the 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision, they argued that Revels did not gain citizenship until at least 1866, with passage of that year’s civil rights act, and perhaps not until the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868. By this logic, Revels could claim that he had been a U.S. citizen for, at most, four years.

Revels and his supporters dismissed the challenge. The Fourteenth Amendment had repealed the Dred Scott decision, they insisted, and they pointed out that long before 1866 Revels had voted in the state of Ohio. Certainly that qualified him as a citizen. “The time has passed for argument. Nothing more need be said …. For a long time it has been clear that colored persons must be senators,” Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner declared, bringing the debate to an end with a stirring speech. “All men are created equal, says the great Declaration, and now a great act attests to this verity. Today we make the Declaration a reality.” By an overwhelming margin, the Senate voted 48 to 8 to seat Revels. Escorted to the well by Senator Wilson, Revels took the oath of office on February 25, 1870.

Three weeks later, the Senate galleries were again filled to capacity as Revels rose to deliver his maiden speech. Seeing himself as a representative of African American interests throughout the nation, Revels spoke against an amendment to the Georgia readmission bill that could be used to prevent blacks from holding state office. “Perhaps it were wiser for me, so inexperienced in the details of senatorial duties, to have remained a passive listener in the progress of this debate,” he began, acknowledging the Senate tradition of waiting a year or more to deliver a major address, “but when I remember that my term is short, and that the issues with which this bill is fraught are momentous in their present and future influence upon the well-being of my race, I would seem indifferent to the importance of the hour and recreant to the high trust imposed upon me if I hesitated to lend my voice on behalf of the loyal people of the South.”

Revels made good use of his time in office, championing education for black Americans, speaking out against racial segregation, and fighting efforts to undermine the civil and political rights of African Americans. When his brief term ended on March 3, 1871, he returned to Mississippi, where he later became president of Alcorn College.

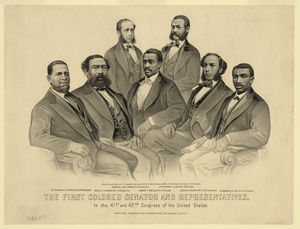

During the Reconstruction Era, a total of 17 African Americans served in the United States Congress, 15 in the House of Representatives and two in the Senate. In 1874 the Mississippi legislature elected Blanche K. Bruce to a full Senate term. Bruce, who had escaped slavery at the outbreak of the Civil War, became the first African American to preside over the Senate in 1879. Another eight decades passed before Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts followed in Revels and Bruce’s historic footsteps to take office in 1967.

The significance of the courageous and pioneering service of Revels, Bruce, and the other African American congressmen of the Reconstruction Era cannot be overstated. Although the struggle to fully achieve equality would continue for years to come, their remarkable accomplishments opened doors for others to follow.