| 202602 12Edward Brooke of Massachusetts—The Bridge Builder

February 12, 2026

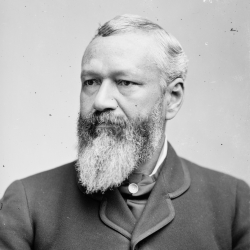

In 2009 former Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the first popularly elected African American senator, received the Congressional Gold Medal in recognition of his “pioneering accomplishments” in public service. During his two Senate terms, Brooke had been a pragmatic lawmaker, building bridges across party and racial lines to chart a course out of the nation’s segregated past, earning his place in the ranks of civil rights pioneers.

On October 28, 2009, former Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the first popularly elected African American senator, stood in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda to receive the Congressional Gold Medal. It was fitting that President Barack Obama, the first African American elected to the presidency, presented the medal to Brooke. Obama highlighted the improbability of a Black, Protestant Republican winning office in a state known for being white, Catholic, and Democratic. As Obama recalled, Brooke “ran for office, as he put it, to bring people together who had never been together before, and that he did.” As the only African American to serve in the Senate during the civil rights era, Brooke brought a unique set of experiences and perspectives to bear on some of the most politically charged issues of his time.1

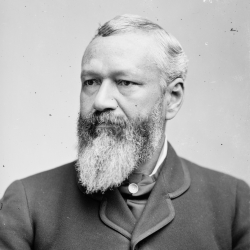

Edward Brooke was born in the District of Columbia in 1919, to Helen, a homemaker, and Edward Jr., a lawyer with the U.S. Veteran’s Administration. Brooke grew up in the Brookland neighborhood of northeastern D.C., at a time when the city’s schools and public accommodations were segregated. He attended Dunbar High School, one of the best performing public high schools for African American students in the country. Following in his father’s footsteps, Brooke enrolled at Howard University, where he served in the school’s ROTC program, graduating in June 1941. Brooke entered the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant with the segregated, all-Black 366th Combat Infantry Regiment stationed at Fort Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts, on December 7, the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. 2

Brooke’s army service was an eye-opening, transformative experience. On the army base in Massachusetts, African American men were denied access to the pools, the exchange, and the officers’ club. “We were treated as second-class soldiers,” Brooke later recalled. Despite lacking any legal training, Brooke successfully defended Black enlisted men in military court—an experience that later led him to law school. In 1944 he sailed with his unit to Europe where he served in North Africa and in the campaign to liberate Italy. Brooke continued to encounter discrimination on base, this time in the form of racist tirades from his commanding officers. With some basic language training, Brooke quickly developed a fluency in Italian, a skill that proved useful in reconnaissance missions with Italian partisans. “My principal job,” he later explained, “was to map mine fields, supply roads, ammunition dumps, to locate concentration camps, and take prisoners for interrogation.” He never forgot the contrast between the freedom and dignity he felt when off base and the racism he experienced on base. Despite the challenges, Brooke earned the rank of captain and was awarded a Bronze Star in 1943 for “heroic or meritorious achievement or service.” While stationed in Italy, he met Remigia Ferrari-Scacco and the two were married in Boston in June 1947.3

Upon his return stateside, Brooke enrolled in Boston University School of Law, earning both a bachelor and a master of laws degree in 1948 and 1950, respectively. He built his own firm in Roxbury, a predominantly African American Boston neighborhood. Encouraged by friends to run for a seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the political neophyte (he did not cast his first vote until age 30) entered both the Republican and Democratic primaries for the house seat in 1950. He won the G.O.P. nomination but lost the general election. He ran again in 1952, with the same result. Stinging from two successive electoral defeats, Brooke continued to practice law while volunteering with various civic organizations, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.4

In 1960 state Republicans urged Brooke to run for secretary of the Commonwealth. He lost the race by a narrow margin to Democrat Kevin White, whose barely disguised racially charged slogan was, “Vote White.” Impressed by Brooke’s strong showing, Republican Governor John Volpe invited him to join his staff. Brooke declined but asked to be appointed chair of the Boston Finance Commission, a municipal watchdog. Volpe obliged, and Brooke transformed the moribund commission into an anti-corruption force, overseeing dozens of investigations, some of which resulted in the resignation of city officials. His oversight work helped him win election as state attorney general in 1962, flipping the office for the GOP. His victory made him the first African American attorney general in the nation and the highest-ranking African American in any state government at the time.5

Three years later, Brooke set his sights on national office. When Republican Senator Leverett Saltonstall announced his retirement in December 1965, Brooke jumped into the race for the open seat. His opponent was former Governor Endicott Peabody, who enjoyed the endorsement of Massachusetts’s popular senator, Democrat Edward “Ted” Kennedy. Brooke won handily, claiming 60 percent of votes cast. Members of the Black press hailed this historic victory as “the most exciting step forward for the Negro in politics” since Reconstruction.6

As an elected official in Massachusetts, Brooke had always been mindful that fewer than 10 percent of his constituents were Black. As attorney general, he had once declared, “I am not a civil rights leader and I don’t profess to be one. I can’t just serve the Negro cause. I’ve got to serve all the people of Massachusetts.” Even so, as the Senate’s only Black member during the peak of the civil rights movement, Brooke was committed to combating racial discrimination, noting in February 1967, “It’s not purely a Negro problem. It’s a social and economic problem—an American problem.”7

To tackle this problem, Brooke worked across party lines. He co-sponsored the Fair Housing Act with Democratic Senator Walter Mondale of Minnesota. Informed by Brooke’s work on the President’s Commission on Civil Disorders, the bill would prohibit housing discrimination in the sale, rental, or financing of housing nationwide. This would become the key provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Passing this ambitious civil rights bill, which faced strong opposition from southern senators, required patience and political acumen. At a time when it took two-thirds of senators present and voting to invoke cloture and overcome a filibuster, Brooke and Mondale painstakingly built a bipartisan coalition to pass the bill. After weeks of debate, and three failed cloture motions, the Senate finally invoked cloture and approved the bill. Brooke stood by the side of President Lyndon B. Johnson on April 11, 1968, as he signed it into law.8

Senator Brooke’s pragmatic approach to politics did not change after Republican Richard Nixon gained the presidency in 1969. While Brooke often supported the administration’s policies, including official recognition of China and nuclear arms limitation, he did not refrain from expressing his differences. He opposed three of the president’s six Supreme Court nominees, citing concerns over their stances on segregation. In November 1973, after the Senate Watergate Committee revealed that the Nixon administration had orchestrated a cover-up of its illegal campaign activities, Brooke became the first Republican senator to publicly call for the president’s resignation. “It has been like a nightmare,” Brooke said. “He might not be guilty of any impeachable offense “[but] because he has lost the confidence of the people of the country … he should step down, should, tender his resignation.”9

During the 1970s, much of Brooke’s legislative attention turned to protecting school desegregation efforts. Stating on national television that he was “deeply concerned about the lack of commitment to equal opportunities for all people,” Brooke charged that the White House neglected Black communities by failing to enforce school integration. Brooke was also central in defeating several antibusing bills initially passed by the House. In 1974 he successfully defeated the Holt amendment to an appropriations bill, introduced by Maryland Representative Marjorie Sewell Holt, that would have effectively ended the federal government’s role in school desegregation. That same year, Brooke helped quash an amendment introduced by Senator Edward Gurney (R-FL) that similarly would have ended busing. In 1975 Brooke reaffirmed his support for busing programs despite the political risk. “It’s not popular—certainly among my constituents. I know that,” he explained. “But, you know, I’ve always believed that those of us who serve in public life have a responsibility to inform and provide leadership for our constituents.”10

Brooke focused on other legislative initiatives as well, including regulating the tobacco industry, providing funding for cancer research programs, investigating connections between civil unrest and poverty, and advocating for a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion.11

Brooke easily won reelection in 1972 but faced a serious primary challenge in 1978, narrowly defeating conservative radio host and political newcomer Avi Nelson. Politically damaged by charges of financial improprieties, he was ultimately defeated by Democrat Paul Tsongas in the general election. Brooke retired from politics to practice law in Washington, D.C. In 2004 President George W. Bush awarded Brooke the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Four years later, Congress awarded him the Congressional Gold Medal, making him just the seventh senator to receive the award at the time. He died in January 2015.12

Edward Brooke did not define himself as a civil rights leader, but as a self-professed “creative Republican” and the Senate’s lone Black member, he sought ways to fight racial discrimination and improve opportunities for African Americans. Brooke was a pragmatic lawmaker, building bridges across party and racial lines to chart a course out of the nation’s segregated past, earning his place in the ranks of civil rights pioneers.13

Notes

1. Martin Kady II, “Brooke gets Congressional Gold Medal,” Politico, October 29, 2009, https://www.politico.com/story/2009/10/brooke-gets-congressional-gold-medal-028864.

2. “An Individual Who Happens to be a Negro,” Time, February 17, 1967.

3. Edward Brooke, Bridging the Divide (Rutgers University Press, 2007), 22.; John Henry Cutler, Ed Brooke; Biography of a Senator (Bobs Merrill, 1972), 27; “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE, Edward William, III,” History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, accessed February 3, 2026, https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/B/BROOKE,-Edward-William,-III-(B000871)/.

4. “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives; Brooke, Bridging, 64.

5. “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives.

6. Edward W. Brooke, The Challenge of Change: Crisis in Our Two-Party System (Boston: Little, Brown, 1966); David S. Broder special, “Saltonstall is Quitting Senate,” New York Times, December 30, 1965; “Brooke Takes Office as Mass. Attorney General,” Chicago Defender, January 17, 1963, 4; “Brooke Takes a Giant Step into National Prominence,” Boston Globe, November 11, 1966, 18; “An Individual,” Time.

7. “Edward W. Brooke, Former U.S. Senator, Oaks Bluff Resident, Dies at 95,” Martha’s Vineyard Times, January 3, 2015, https://www.mvtimes.com/2015/01/03/edward-w-brooke-former-u-s-senator-oak-bluffs-resident-dies-95/; “An Individual,” Time.

8. Rigel C. Oliveri, “The Legislative Battle for the Fair Housing Act (1966–1968),” in Gregory D. Squires, ed., The Fight for Fair Housing: Causes, Consequences and Future Implications of the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act (New York: Routledge, 2017); “Congress Passes Rights Bill: Bars Bias in 80% of Housing,” Boston Globe, April 11, 1968, 1; “President Signs Civil Rights Bill: Pleads for Calm,” New York Times, April 12, 1968, 1; Civil Rights Act of 1968, Title VIII, Fair Housing, Public Law 90-284, 82 Stat. 73 (1968).

9. Brooke, Bridging, 191, 202, 203–4; “A Portrait of Racism,” Boston Globe, February 8, 1970, A25; “Brooke to Vote Against Nominee,” Hartford Courant, February 26, 1970, 5; “GOP Senator Brooke Asks Nixon to Quit,” Atlanta Constitution, November 5, 1973, 1A; “Carswell Disavows ’48 Speech Backing White Supremacy,” New York Times, January 22, 1970.

10. “Brooke Says Nixon Shuns Black Needs,” New York Times, March 12, 1970; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives; Richard D. Lyons, “Busing of Pupils Upheld in a Senate Vote of 47-46,” New York Times, May 16, 1974; Jason Sokol, “How a Young Joe Biden Turned Liberals Against Integration,” Politico, August 4, 2015, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/08/04/joe-biden-integration-school-busing-120968/.

11. Brooke, Bridging, 186, 216–7, 220.

12. Dane Morris Netherton, “Paul Tsongas and the Battles Over Energy and the Environment, 1974-80,” Ph.D. diss., Washington State University (May 2004): 130, 144.; “U.S. Senators Awarded the Congressional Gold Medal,” United States Senate, accessed February 3, 2026, https://www.senate.gov/senators/Senators_Congressional_Gold_Medal.htm.

13. Gary Orfield, “Senator Edward Brooke: A Personal Reflection,” The Civil Rights Project, accessed January 8, 2015, https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/senator-edward-brooke-a-personal-reflection-by-gary-orfield/; Sally Jacobs, “The Unfinished Chapter,” Globe Magazine, March 5, 2000, https://cache.boston.com/globe/magazine/2000/3-5/featurestory2.shtml.

|

| 202502 26Reconstruction Louisiana and the Case of PBS Pinchback

February 26, 2025

In February 1870, Hiram Revels of Mississippi made history as the first Black American to be elected to the United States Senate. Revels served only 13 months, but five years later the Mississippi legislature, still under the control of Republicans who were swept into office as part of post-Civil War Reconstruction, elected Blanche K. Bruce, making him the first Black American elected to a full Senate term. Often forgotten, however, is another pioneering Black politician, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback of Louisiana, who was elected to the Senate in 1873 but never allowed to take his seat.

In February 1870, Hiram Revels of Mississippi made history as the first Black American to be elected to the United States Senate. Revels served only 13 months, but five years later the Mississippi legislature, still under the control of Republicans who were swept into office as part of post-Civil War Reconstruction, elected Blanche K. Bruce, making him the first Black American elected to a full Senate term. Often forgotten, however, is another pioneering Black politician, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback of Louisiana, who was elected to the Senate in 1873 but never allowed to take his seat.

Pinchback’s story offers a window into an era of political upheaval in the United States, when Black Americans fought to exercise their newly won political and civil rights in the South, and former Confederates sought, often violently, to reclaim power from Republican-dominated Reconstruction governments in which a large number of African Americans held office. Throughout the 1870s, members of the Senate and House of Representatives debated the power of Congress to ensure fair elections in the South and enforce protections enshrined in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.1

Pinchback, who went by the initials PBS but was “Pinch” to his friends, was born in 1837 to a formerly enslaved mother, Eliza Stewart, and her white enslaver, Major William Pinchback. Major Pinchback had freed and married Stewart and moved the family to Mississippi. When Major Pinchback died in 1848, Stewart, denied the Pinchback estate by Mississippi courts and fearing re-enslavement by Major Pinchback's family, moved with her children to Cincinnati, Ohio, where PBS Pinchback was already attending boarding school. At 12 years old, Pinchback ended his formal education and went to work on Mississippi river boats, eventually falling in with a gambler who instructed him in the art of dice and card games.2

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Pinchback made his way to Union-occupied New Orleans where he enlisted with the Union army. He was tasked by General Benjamin Butler with recruiting a company of Black soldiers and was commissioned as the company’s captain. He resigned in September 1863 after enduring poor treatment from white troops and officers. A gifted orator, Pinchback went north after the war to promote Black suffrage in the South and later settled in Alabama to help freedmen organize for their political rights.3

After the Radical Republicans in Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act in 1867 to remove former Confederates from power and protect Black rights, Pinchback returned to New Orleans to work with Republican officials in the city. A speech he delivered at the Republican state party convention in defense of Black civil rights led to Pinchback’s appointment to the party’s executive committee, followed by his election to the state constitutional convention in 1867. When the constitutional convention first met in 1866, a white mob had disrupted the proceedings and sparked what came to be known as the Mechanics Institute Massacre (the Institute was being used as the State House at the time), which left 46 African Americans dead and another 60 injured. At the 1867 constitutional convention, undeterred by the threat of violence, Pinchback led the drafting of a civil rights article for the new constitution that granted Blacks the right to vote and disenfranchised former Confederates.4

Impressed with his performance at the convention, Louisiana Republicans floated Pinchback as the party’s nominee for governor, but he demurred and supported a young white attorney from Illinois, Henry Clay Warmoth, who won election in April 1868 along with other Radical Republicans, despite widespread violence and intimidation against Black voters. Meanwhile, Pinchback won election to the state senate, but only after a state committee on elections determined there had been fraud in the balloting and awarded him the seat.5

In the years that followed, Republicans in Louisiana and Washington split into contending factions over the future of Reconstruction, forcing Pinchback to negotiate a rapidly shifting political landscape. The state’s Black Republicans grew frustrated with Governor Warmoth as he failed to support strong civil rights legislation and curried favor with white Democrats by, among other things, appointing former Confederates to state office. Pinchback initially continued to support Warmoth and was rewarded with election as president of the Senate, a post that carried with it duties as acting lieutenant governor. But in 1872, when Warmoth announced his support for presidential candidate Horace Greeley, a Democrat backed by the new Liberal Republican Party who came to oppose Radical Reconstruction in favor of reconciliation with former Confederates, Pinchback broke with his political patron. Back in the good graces of the state’s regular Republicans, Pinchback campaigned for President Ulysses S. Grant and for continued federal support for Black civil rights in the South. In the race for Louisiana governor, Pinchback stumped for U.S. Senator William Pitt Kellogg against Democrat John McEnery, who ran with the support of Warmoth and the state’s Liberal Republicans.6

The 1872 elections left Louisiana in political chaos. McEnery and his coalition of Democrats and Liberal Republicans declared themselves the victors, while the state’s Republicans charged that they would have won if not for widespread fraud and violence against Black voters. When Governor Warmoth took control of the state’s election board to certify the Democratic victory in violation of a federal court order, the district judge intervened, and federal troops took control of the State House. On December 9, 1872, the Republicans passed articles of impeachment against Warmoth, which under Louisiana law suspended him from office pending trial. As a result, Pinchback became the acting governor, the first Black governor of a state in the nation’s history. When the newly elected government was to meet on January 14, both sides organized rival governments, each claiming to be the legitimate representatives of the people. Backed by the federal courts, the Republicans gathered in the State House and inaugurated Kellogg as governor, while the Democrats organized their own legislature at City Hall and swore in McEnery.7

Louisiana’s political troubles soon reached the U.S. Senate, with Pinchback at the center. When Kellogg resigned his Senate seat to take over as governor, the competing legislatures each elected a replacement to complete the final weeks of Kellogg’s term. Both Democrat William McMillen and Republican John Ray presented their credentials—one signed by McEnery and the other by Kellogg, respectively—to the Senate. At the same time, the Republican legislature elected Pinchback to the Senate for the full term beginning on March 4, 1873, and the Democratic coalition legislature elected McMillen for the seat.

A Senate increasingly divided over Reconstruction policies and the role of the federal government in enforcing Black political rights in the South took up the question of who held rightful claim to Louisiana’s Senate seat. The Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, chaired by Radical Republican leader Oliver Morton of Indiana, launched an investigation into “whether there is any existing State government in Louisiana” that could name a senator. After a month of examination, the committee recommended rejecting both sets of credentials and offered a bill to mandate new elections in the state. A committee majority—which included Republicans Matthew Carpenter of Wisconsin, John Logan of Illinois, James Alcorn of Mississippi, and Henry Anthony of Rhode Island—concluded that if the election had “been fairly conducted and returned, Kellogg … and a legislature composed of the same political party, would have been elected,” and that recognizing the McEnery government without scrutinizing the election returns “would be recognizing a government based upon fraud, in defiance of the wishes and intention of the voters of that State.” But the majority also charged that the Republican legislature in Louisiana had no legal authority, strongly condemned the intervention of the federal courts, and concluded that the Republicans had “usurped” the government by tossing out the Democratic victory. In the minority, Democrats on the committee called for McMillen to be seated, arguing that Congress had no role to play in state elections and could not throw out the Democrats’ “official” results. Only Chairman Morton made the case that the Republicans were entitled to the seat unconditionally. The full Senate took no action, however, and the seat remained vacant.8

When new senators were sworn in at the start of the 43rd Congress on March 4, 1873, the Senate did not address the Louisiana seat. That spring, white paramilitary groups continued a campaign of violence against Black Louisianans, including the infamous Colfax Massacre in April when 80 to 100 African Americans were killed. Despite the ongoing political violence, a growing number of senators began to question federal intervention in the South. When the Senate convened for the first regular session in December 1873, the Committee on Privileges and Elections took up Pinchback’s case but reported that they were “evenly divided” and “beg[ed] leave to be discharged from further consideration.” Pinchback faced yet another setback in January 1874 when his champion in the Senate, Oliver Morton, heard rumors that Pinchback had secured his election through bribes and wavered in his commitment to the case. When Morton moved for a new investigation into Pinchback’s personal conduct by the Committee on Privileges and Elections, Matthew Carpenter instead introduced a resolution calling for new elections in Louisiana. Neither resolution was put to a vote, the case languished for the remainder of 1874, and the seat remained vacant.9

Pinchback’s case received new life in January 1875 when, after another contested election in 1874, Louisiana’s Republican legislature again elected him to the Senate “in order that all doubts or questioning of the title … be entirely silenced.” Morton set his qualms aside and threw himself once again behind securing Pinchback his seat. Senate Democrats refused to concede the fight and launched a filibuster that kept the Senate in session all night on February 17. They had the support of a number of Republicans, such as George Edmunds of Vermont, who had become highly critical of Reconstruction policy and the federal government’s role in supporting Black voters in the South. The debate continued on and off for weeks, with Republicans railing against the frauds and intimidation that had allowed McEnery and the Democrats to claim victory in the 1872 elections, and Democrats dismissing Kellogg as a “usurper.” By the end of the session, Republicans had still failed to get a vote on the Pinchback resolution.10

Meanwhile, in December 1874, responding to a plea from President Grant, the House of Representatives had created a committee to investigate Louisiana’s 1874 elections and resolve the political deadlock. New York Representative and future Vice President William Wheeler produced a plan, later known as the Wheeler Compromise, whereby the Democrats would accept Kellogg’s position as governor and be granted a majority of seats in the state assembly, and the Republicans would be given control of the state senate. Kellogg and both parties accepted the plan in April 1875, and in January 1876 this newly constituted Louisiana legislature declared the Senate seat vacant and elected a new senator, James B. Eustis, a Democrat. A trio of Republican Louisiana state senators submitted a statement to the Senate lamenting “being unable … to elect a gentleman strictly of our own party faith” but defending Eustis’s election as “an act in the interests of peace and prosperity, and a healthy and lasting good-will among all here at home.” This willingness by Republicans to compromise at the expense of Black voters signaled the beginning of the end of Reconstruction in Louisiana.11

Morton refused to accept that the Louisiana seat was vacant for Eustis to claim and in February 1876 put Pinchback’s case before the Senate one last time. Blanche Bruce of Mississippi, who had entered the Senate the previous year, used the occasion to deliver his maiden speech. Bruce told his Republican colleagues that to reject Pinchback amounted to the federal government turning its back on Louisiana and its Black citizens. In a closed executive session, Bruce was even more forceful. “If when the Louisiana case is again called, it be not settled,” he stated, “I will resign my seat in a body which presents this spectacle of asinine conduct.”12

The Senate did settle the case, and Bruce did not resign. On March 8, 1876, more than three years after Pinchback had arrived in Washington to take the oath of office, the Senate rejected his claim to the seat. Seated at the back of the Chamber while the final debate and vote took place, Pinchback reportedly “acted as one relieved, and who felt the great strain was over.” As a consolation, the Senate awarded him $16,000, approximately what he would have earned as a senator during those three years.13

Pinchback returned to New Orleans where he remained an important political figure for a time, even as Democratic lawmakers consolidated their power in the former Confederate states under Jim Crow laws. In a letter to Blanche Bruce, he called himself “the liveliest corpse in the dead South.” Pinchback settled back in Washington in the 1890s and remained a presence at banquets and parties but increasingly seemed a relic of a bygone political era, when Black southerners had won election to federal office. Pinchback died in 1921 at the age of 84. After Blanche K. Bruce left the Senate in 1881, more than 80 years passed before another African American—Edward Brooke of Massachusetts—won election to the Senate.14

Notes

1. History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, Office of the Historian, Black Americans in Congress, 1870–2007, “’The Fifteenth Amendment in Flesh and Blood:’ 1870–1901,” accessed February 18, 2025, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Essays/Fifteenth-Amendment/Introduction/.

2. Philip Dray, Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction Through the Lives of the First Black Congressmen (Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 103; George H. Devol, Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi, (Home Book Co., 1894), 216–17.

3. Charles Vincent, Black Legislators in Louisiana During Reconstruction (Southern Illinois University Press, 2011), 8–10; James Haskins, The First Black Governor: Pinkney Benton Stewart Pinchback (MacMillan, 1973; African World Press, 1996), 24–25, 38–45.

4. Haskins, First Black Governor, 47–54, 56–60; Dray, Capitol Men, 28–32, 106.

5. Dray, Capitol Men, 107.

6. Dray, Capitol Men, 109–110, 117–118, 124–127; Haskins, First Black Governor, 82–83, 100–102; “New Orleans,” New York Times, January 21, 1872, 1.

7. Dray, Capitol Men, 134. For the most complete details of the events surrounding the elections, see Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Louisiana Investigation, S. Rpt. 457, 42nd Cong., 3rd sess., February 20, 1873.

8. S. Rpt. 457, XLIV.

9. Congressional Record, 43rd Cong., 1st sess., December 15, 1873, 188; January 30, 1874, 1036–58; March 3, 1874, 1926–27; Haskins, First Black Governor, 196–99, 202–4; Dray, Capitol Men, 224–25. In the meantime, Pinchback had been on the ballot for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1872, but the election was contested and remained unresolved for much of the 43rd Congress. He pleaded his case to the House of Representatives in June 1874 to obtain the at-large seat, but the House awarded the seat to his Democratic opponent.

10. “In Louisiana,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 13, 1875, 1; Resolution that Senate recognize validity of credentials of P. B. S. Pinchback, S. Mis. Doc. 16, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., December 23, 1874; Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Credentials of P. B. S. Pinchback, for seat in Senate from Louisiana, S. Rpt. 626, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., February 8, 1875.

11. James T. Otten, “The Wheeler Adjustment in Louisiana: National Republicans Begin to Reappraise Their Reconstruction Policy,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 13, no. 4 (1972): 349–67; Views of certain State senators on election of Hon. J. B. Eustis as United States Senator from Louisiana, S. Mis. Doc. 41, 44th Cong, 1st sess., January 26, 1876.

12. New Orleans Times, February 17, 1876, quoted in Sadie Daniel St. Clair, The National Career of Blanche Kelso Bruce (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1947), 96–97.

13. Congressional Record, 44th Cong., 1st sess., March 8, 1876, 1557–58; New Orleans Republican, March 14, 1876, quoted in Haskins, 221; Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Question of allowance proper to be made to P. B. S. Pinchback, late contestant for seat in Senate from Louisiana, S. Rpt. 274, 44th Cong., 1st sess., April 17, 1876.

14. Haskins, First Black Governor, 241; “Pinchback, Louisiana Governor in 1872, Dead,” Washington Post, December 22, 1921, 10.

|

| 202402 28Integrating Senate Spaces: Louis Lautier, Alice Dunnigan, Thomas Thornton and Christine McCreary

February 28, 2024

African American men and women have worked on Capitol Hill since Congress moved to the new capital in the District of Columbia in 1800. Black laborers, enslaved and free, helped to build the Capitol. They worked as messengers, groundskeepers, carpenters, and cafeteria workers. In the 20th century, as African Americans moved into professional positions, they began to challenge inequality in their workplaces. Years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 legally ended segregation, four courageous individuals demanded the integration of Senate spaces.

African American men and women have worked on Capitol Hill since Congress moved to the new capital in the District of Columbia in 1800. Black laborers, enslaved and free, helped to build the Capitol. In the 19th century, African Americans worked as messengers, groundskeepers, pages, carpenters, and cafeteria workers. In the 20th century, as they began to move into professional positions, they challenged the discriminatory practices that prevailed in their workplaces. Years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 legally ended segregation, four courageous individuals demanded the integration of Senate spaces.

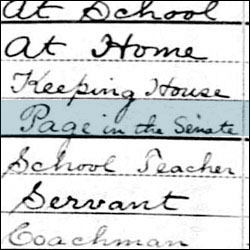

In January 1946, Louis Lautier, a correspondent for the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association, applied to the Senate Standing Committee of Correspondents for admission to the daily press gallery. In 1884 the Senate had made the Standing Committee, a group of elected members of the press gallery, responsible for credentialing congressional correspondents. Under Senate rules, the daily press gallery was open to correspondents “who represent daily newspapers or newspaper associations requiring telegraphic service.” Most African American papers were published weekly. A separate periodicals gallery served reporters of weekly magazines, not newspapers. Rules that seemingly were intended to prevent lobbyists from moonlighting as correspondents effectively made the Senate’s daily press gallery and the periodicals gallery off-limits to Black reporters. As Senate Historian Emeritus Donald Ritchie explains, “There [was] never a rule of the press gallery that says, ‘You have to be a white man,’ but the rules are written in such a way that that’s the only people who could get in.1

African American reporters had applied for admission on occasion despite these regulations, but their applications had all met the same fate—rejection. When rejecting Lautier’s application for admission in January 1946, the Standing Committee explained, “Inasmuch as your chief attention and your principal earned income is not obtained from daily telegraphic correspondence for a daily newspaper, as required under [Senate rules], you [are] not eligible.” Lautier then revised his application, noting that he was “jointly employed” by the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association, “with each organization paying half of my salary.” The Standing Committee stood by its initial decision, so Lautier appealed directly to the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, which had jurisdiction over the press galleries. The Rules Committee chairman, Democrat Harry Byrd of Virginia, did not intervene. Undeterred, Lautier resubmitted his application to the Standing Committee in November 1946.2

When the 80th Congress convened for its first session in January 1947, Republicans gained control of the Senate for the first time since 1933. One of the first orders of business facing the Senate was the seating of Senator Theodore Bilbo, a vocal white supremacist. In 1946 a Senate committee had investigated allegations by Black Mississippians that Bilbo had “conducted an aggressive and ruthless campaign” to deny Blacks the right to vote in the 1946 Democratic primary. A second, separate Senate inquiry had concluded that Bilbo had accepted “gifts, services, and political contributions” from war contractors whom he had assisted in securing government defense contracts. Lautier intended to cover the Senate debate, but without admittance to the press galleries, he was forced to wait in long lines for a seat in the public galleries, where Senate rules prohibited him from taking notes.3

Weeks later, on March 4, “after exhaustive deliberations and a personal hearing,” the Standing Committee again rejected Lautier’s application. Editorials in the national press urged the Standing Committee to reconsider its decision, and Lautier appealed to the new Rules Committee chairman, Senator C. Wayland “Curley” Brooks of Illinois. “Since the Standing Committee of Correspondents has acted arbitrarily in refusing me admission to the press galleries, and since under the interpretation of the rules Negro correspondents are barred solely because of their race or color, it appears that the Senate Rules Committee has the responsibility and duty to see that this gross discrimination against the Negro press is removed,” Lautier wrote.4

Senator Brooks, who had recently encountered separate allegations of racial discrimination in Senate facilities, readily agreed to investigate Lautier’s case. On March 18, 1947, Chairman Brooks convened a hearing to consider both Lautier’s application and the issue of discrimination in Senate dining facilities. “In the Capitol of the greatest free country in the world, we certainly should have no discrimination,” Brooks declared.5

The hearings first addressed Lautier’s application. Lautier testified that he met the qualifications for admittance to the daily press gallery under the existing rules. “I believe that I comply with the rules, if reasonably interpreted … because daily I gather news for the Atlanta Daily World.” While the rules had not been designed to “exclude Negro correspondents” from the press galleries “solely because of their race or color … that is the practical effect of the interpretation given the rules by the Standing Committee of Correspondents,” Lautier explained to committee members. Lautier described how the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association rendered a vital service to African Americans by focusing on issues of particular significance to them. At a recent hearing to consider amending the cloture rule, for example, Louisiana senator John Overton had stated that “the Democratic South stands for white supremacy.” Overton’s statement, as well as debates about proposed changes to Senate rules and procedures, had been “inadequately reported by the white daily press,” Lautier explained. His readers relied upon Black correspondents to be “intelligently informed of what is going on in the Congress.”6

Testifying in defense of the decision to deny Lautier’s admission, the chairman of the Standing Committee, Griffing Bancroft of the Chicago Sun, maintained that race had not played a role in its decision making and recommended a rules revision “so that facilities could be provided for the weekly papers.” Brooks pressed Bancroft; couldn’t the situation be immediately resolved by admitting Lautier? That is not a long-term solution, Bancroft replied, because without revising the rules for admission, African American correspondents writing for weekly papers would continue to be denied admission to the daily press gallery and the periodicals gallery. Lautier believed that a rules change would not be required in his case, because “under a reasonable interpretation of [the current] rules I am entitled to admission.” Members of the Rules Committee agreed with Lautier and voted unanimously to approve his application for admission to the Senate daily press gallery. It was only a partial victory for Black correspondents, however, as it was not clear if Lautier’s admission had paved the way for other Black reporters.7

At the same time that Lautier was appealing the decision of the Standing Committee for credentials to the daily press gallery, Alice Dunnigan, the new Washington correspondent for the Associated Negro Press, had just arrived in the city to cover the Bilbo floor debate. Unaware of the Lautier case, Dunnigan submitted applications to the Standing Committee for admission to the daily press gallery and to the periodicals gallery, but she waited weeks with no answer. She called repeatedly to inquire about her application and made personal visits to the Capitol, “probably making a nuisance of [herself].” Even after Chairman Brooks’s hearing on Lautier’s application, Dunnigan still did not get an answer. After some investigation, Dunnigan learned that she faced another kind of discrimination. The founder and director of her news organization, Claude Barnett, had failed to provide a letter of recommendation in support of Dunnigan’s application, as required by the Standing Committee. When Dunnigan confronted Barnett about the issue, he explained, “For years, we have been trying to get a [Black] man accredited to the Capitol Galleries and have not succeeded. What makes you think that you—a woman—can accomplish this feat?” Dunnigan persisted, however, and Barnett eventually sent his letter to the Standing Committee, who promptly approved her application for admission to the daily gallery in June 1947. “My acceptance received widespread publicity,” Dunnigan later recalled, “and the Republican-controlled Congress received credit for opening the Capitol Press Galleries” to African American reporters.8

Chairman Brooks’s hearing on the Senate press galleries had a positive impact on integrating those Senate spaces, but the fight to integrate the Senate’s dining facilities took a bit longer. Brooks had appointed World War II army veteran Thomas N. Thornton, Jr., an African American, to a position as a mail carrier in the Senate post office on February 20, 1947. One day in early March, Thornton stopped at the luncheonette in the Senate Office Building (now the Russell Senate Office Building) and ordered a sandwich and coffee. A waitress asked Thornton to take his order to go, but he refused, sat down at a table, and ate his meal. Though Senate rules prohibited discrimination in Senate facilities, Thornton had violated a long-standing Senate practice of “whites only” dining facilities. Word of Thornton’s actions spread, and Washington Post syndicated columnist Drew Pearson reported that Sergeant at Arms Edward McGinnis had reprimanded Thornton and advised him not to eat again inside Senate dining facilities. During the March 1947 Rules Committee hearings about discrimination in Senate facilities, the Architect of the Capitol, David Lynn, whose responsibilities included the operation of Senate restaurants, assured Chairman Brooks that discrimination in Senate dining facilities would not be tolerated. “When this incident happened, it was purely a misunderstanding on the part of a new [restaurant] employee or it would never have happened,” reported the director of Senate dining facilities, D. W. Darling.9

Despite these assurances, de facto segregation in the Capitol’s dining rooms persisted for years. Not long after joining Senator Stuart Symington’s personal staff in 1953, Christine McCreary attempted to eat in the Senate cafeteria. When an anxious hostess reminded her that the cafeteria served “only … people who work in the Senate,” McCreary explained, patiently, that she worked for Senator Symington. The hostess demurred, then reluctantly invited McCreary to “take a seat anyplace you can find.” Diners gawked as McCreary passed through the serving line with tray in hand. “You could hear a pin drop,” she later recalled. Silently enduring the “snide remarks” of those who disapproved of her effort, McCreary remembered her first years of Senate service as “a lonesome time.” But she refused to give up. “I went back [to the cafeteria] the next day, and the next day, until finally they got used to seeing me coming.”10

As we commemorate Black History Month, let us acknowledge the perseverance and determination of members of the Senate community, including Lautier, Dunnigan, Thornton, and McCreary, and their remarkable courage in challenging the Senate’s long-standing discriminatory practices.

Notes

1. Donald A. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 109–110; “Donald Ritchie, Senate Historian 1976–2015,” Oral History Interviews, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.

2. “Credentials,” January 1946, Louis Lautier Case, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office: Senate Press Gallery, Standing Committee on Correspondents.

3. Special Committee to Investigate Senatorial Campaign Expenditures, Investigation of Senatorial Campaign Expenditures, 1946, S. Rep. 80-1, 80th Cong., 1st sess., January 3, 1947; Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, Investigation of the National Defense Program, Additional Report, Transactions Between Senator Theodore G. Bilbo and Various War Contractors, S. Rep. 79-110, Part 8, January 2, 1947, 79th Cong., 2nd sess., 2; Donald A. Ritchie, Reporting from Washington: The History of the Washington Press Corps (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 35.

4. Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery and Hearing on Reports of Discrimination in Admission to Senate Restaurants and Cafeterias, 80th Cong., 1st sess., March 18, 1947, 5–6, 47–52.

5. Ibid., 70.

6. Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 4, 10; Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Amending Senate Rule Relating to Cloture: Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Rules and Administration on S. Res. 25, 30, 32, and 39, 80th Cong., 1st sess., January 28, February 4, 11, 18, 1947.

7. Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 9, 38.

8. Alice Dunnigan, Alone Atop the Hill: The Autobiography of Alice Dunnigan, Pioneer of the National Black Press (Athens: The University Press of Georgia, 2015) 107–9, 110–12; Ritchie, Reporting From Washington, 39–40; “Credentials,” January 1947, Alice Dunnigan Case, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office: Senate Press Gallery, Standing Committee on Correspondents.

9. Kenneth O’Reilly, “The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson,” Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 17 (Autumn, 1997), 117–21; Rodney Dutcher, “Behind the Scenes in Washington,” Times-News, Hendersonville, N.C., March 3, 1934; Drew Pearson, “Color Bar in Senate Restaurant,” Washington Post, 8 Mar 1947, 9; Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 61–64, 66; Report of the Secretary of the Senate, July 1, 1946, to January 3, 1947 and January 4, 1947, to June 30, 1947, S. Doc. 80-117, 80th Cong., 2nd sess., January 7, 1948, 260.

10. "Christine S. McCreary, Staff of Senator Stuart Symington, 1953–1977 and Senator John Glenn, 1977–1998," Oral History Interviews, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.

|

| 202312 11In Form and Spirit: Creating the Statue of Freedom

December 11, 2023

The massive bronze Statue of Freedom has been perched atop the great dome of the United States Capitol since its assembly was completed on December 2, 1863, amidst the pall of civil war. As the crowning feature of the building’s new cast-iron dome, it offered a glimmer of hope that the nation would endure. The continuation of the construction of the dome had served as a symbolic backdrop during the dark war years, but Freedom’s journey to the top of the dome had begun years before.

The massive bronze Statue of Freedom has been perched atop the great dome of the United States Capitol since its assembly was completed on December 2, 1863, amidst the pall of civil war. As the crowning feature of the building’s new cast-iron dome, it offered a glimmer of hope that the nation would endure. The continuation of the construction of the dome had served as a symbolic backdrop during the dark war years, but Freedom’s journey to the top of the dome had begun years before.

The Capitol underwent a major transformation during the Civil War. On March 4, 1861, with war looming, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his first inaugural address in the shadow of the half-finished dome. The building was in the midst of a major expansion project that had begun 10 years earlier and included the construction of two large wings and a new, taller dome. At the onset of the war, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, the superintendent of the Capitol extension and dome construction, observed that the government had “no money to spend except in self defense” and issued the order to stop working. Despite this order, the iron foundry hired to construct the dome, Janes, Fowler and Kirtland, continued the project without pay. The foundry worried that the cast iron materials already procured would be damaged or destroyed if installation was delayed.1

Members of Congress, many of whom shared similar concerns, debated a resolution to restore funding in the spring of 1862. “Every consideration of economy, every consideration of protection to this building, every consideration of expediency requires that it should be completed, and that it should be done now,” Vermont senator Solomon Foot appealed to his fellow senators. “To let these works remain in their present condition is, in my judgment, to say the least of it, the most inexcusable, needless, and extravagant waste and destruction of property,” he argued. “We are strong enough yet, thank God, to put down this rebellion and to put up this our Capitol at the same time.” Congress restored construction funding in April 1862, and the foundry’s dome contract was renewed. Slowly and steadily, the massive dome became a reality during those difficult war years. The vision of this continuing endeavor provided inspiration during this perilous time. “If people see the Capitol going on, it is a sign we intend the Union shall go on,” remarked President Abraham Lincoln. “War or no war, the work goes steadily on,” reported the Chicago Tribune.2

To crown the new dome, Architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter, who designed the cast-iron structure, called for a large statue, which he originally conceived as an allegorical figure “holding a liberty cap”—a cloth cap worn by the formerly enslaved in Ancient Greece and Rome that later became a popular symbol of the American and French Revolutions. In 1855 Meigs asked American sculptor Thomas Crawford, who had produced other sculptural pieces for the Capitol project, to create a representation of Liberty for the dome’s statue. Working in his studio in Rome, Crawford instead proposed a figure representing “Freedom triumphant in War and Peace.” His first design, a female holding an olive branch in one hand and a sword in the other, was made before he realized that the sculpture needed more height and a taller pedestal. His second sketch, which Crawford said represented “Armed Liberty,” was a female figure in classical dress wearing a liberty cap adorned with stars and holding a shield and wreath in one hand and a sword in the other.3

Upon receiving Crawford’s second design, Meigs rightly anticipated that his superior, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, a Southern enslaver (and future president of the Confederacy) who oversaw the Capitol construction project, would object to the inclusion of the liberty cap. “Mr. Crawford has made a light and beautiful figure of Liberty…. It has upon it the inevitable liberty cap, to which Mr. Davis will, I do not doubt, object,” Meigs recorded in his journal. Indeed, Davis did object. “History renders [the liberty cap] inappropriate to a people who were born free and would not be enslaved,” Davis argued, willfully ignoring the millions of enslaved people who toiled across the nation. “[S]hould not armed Liberty wear a helmet?” Davis offered. Crawford’s third and final design reflected Davis’s suggestion. Freedom was clad with a helmet, "the crest of which is composed of an eagle’s head and a bold arrangement of feathers, suggested by the costume of our Indian tribes," Crawford explained.4

Once the statue design was approved, Crawford prepared a plaster model in his studio, his last work before he fell ill and died in 1857. Divided into five separate pieces, the model was shipped to America. After a long and arduous journey in a ship plagued by leaks, all of the pieces finally arrived in Washington in March 1859. An Italian craftsman working in the Capitol reassembled the model, covering all the seams with fresh plaster, and it was temporarily displayed in the old House Chamber (now known as Statuary Hall). Clark Mills, the owner of a local iron foundry, was hired to cast the statue in bronze in 1860. When the time came to disassemble the plaster model for casting, the Italian craftsman demanded additional pay from Mills, claiming that he alone knew how to separate the model. Mills turned instead to one of his foundry workers, an enslaved African American artisan named Philip Reid, who skillfully devised a method of separating the plaster model so that the individual sections could be cast and the bronze statue assembled. Reid labored seven days a week on Freedom, the only worker in Mills’s foundry paid to attend to the statue on Sundays, according to government records. Reid's rate of pay was $1.25 per day; however, as an enslaved man, he was likely only permitted to keep his Sunday earnings. While Reid was one of many enslaved people who helped to build the Capitol, he is unique in that his name has been documented in official records. “Philip Reid’s story is one of the great ironies in the Capitol’s history,” architectural historian of the Capitol William C. Allen observed, “a workman helping to cast a noble allegorical representation of American freedom when he himself was not free.”5

More ironic yet was the fact that when the statue was finally placed atop the dome on December 2, 1863, Reid was a free man, liberated by the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act in 1862 . Reporting from Washington that December day, a correspondent for the New York Tribune recounted Reid’s central role in the creation of Freedom, and reflected, “Was there a prophecy in that moment when the slave became the artist, and with rare poetic justice, reconstructed the beautiful symbol of freedom for America?” The installation of the Statue of Freedom proved to be symbolic, signifying the enduring nation in a time of civil war. A solemn ceremony marked completion of the dome and the placement of Freedom. The “flag of the nation was hoisted to the apex of the dome,” wrote an observer, “a signal that the ‘crowning’ had been successfully completed.” A salute was ordered to commemorate the event, “as an expression…of respect for the material symbol of the principle upon which our government is based.” The 12 forts that guarded the capital city answered with cannon fire when artillery fired a 35-gun-salute—one gun for each state, including those of the Confederacy.6

“Freedom now stands on the Dome of the Capitol of the United States,” wrote the Commissioner of Public Buildings, Benjamin Brown French, in his journal; “May she stand there forever, not only in form, but in spirit.” It was an appropriate finale to a year that began with Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. “Let us indulge the hope that our posterity to the end of time may look upon it with the same admiration which we do today,” one observer wrote of Freedom that December day, “and an unbroken Union three years since would have viewed this glorious symbol of patriotism and achievement of art.” Indeed, the nation emerged from the Civil War damaged but intact, improved by the permanent emancipation of four million African Americans in December 1865. 7

Notes

1. William C. Allen, The Dome of the United States Capitol: An Architectural History (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1992), 55.

2. Congressional Globe, 37th Cong., 2nd sess., March 25, 1862, 1349; Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, eds., Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 147; “The Capitol Improvements,” Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1863, 1.

3. “Statue of Freedom,” Architect of the Capitol, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/statue-freedom; "The Liberty Cap in the Art of the U.S. Capitol," Architect of the Capitol, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/blog/liberty-cap-art-us-capitol; William C. Allen, History of the United States Capitol: A Chronicle of Design, Construction, and Politics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 246; Allen, Dome, 42.

4. Wendy Wolff, ed., Capitol Builder: The Shorthand Journal of Montgomery C. Meigs, 1853–1859, 1861 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2001), 332; Allen, Dome, 42–43.

5. Allen, Dome, 42–43; John Philip Colletta, "Clark Mills and His Enslaved Assistant, Philip Reed: The Collaboration that Culminated in Freedom," Capitol Dome 57, (Spring/Summer 2020): 19; "History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the United States Capitol," report prepared by William C. Allen, Architectural Historian, Office of the Architect of the Capitol, June 1, 2005, p. 16, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office.

6. “The Statue of Freedom,” correspondence of the New York Tribune, reported in the Chicago Tribune, December 14, 1863, 1; "The Statue on the Capitol Dome," National Intelligencer, December 3, 1863, 3; S. D. Wyeth, The Rotunda and Dome of the US. Capitol (Washington, D.C.: Gibson Brothers, 1869), 193.

7. Benjamin Brown French, Witness to the Young Republic, A Yankee’s Journal, 1828–1870 (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1989), 439; "The Statue on the Capitol Dome," National Intelligencer, December 3, 1863, 3.

|

| 202302 02The Power of a Single Voice: Carol Moseley Braun Persuades the Senate to Reject a Confederate Symbol

February 02, 2023

On July 22, 1993, senators were considering amendments to a national service bill when suddenly, the Senate Chamber doors flew open and Illinois senator Carol Moseley Braun rushed to her desk and sought recognition. North Carolina senator Jesse Helms had proposed an amendment to renew a patent to the United Daughters of the Confederacy for an insignia that featured the first national flag of the Confederate States of America. Senator Moseley Braun, the first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, intended to stop that amendment.

July 22, 1993, began as an ordinary day as senators considered amendments to the National and Community Service Act of 1990. That routine business was suddenly interrupted, however, when the Senate Chamber doors flew open and Illinois senator Carol Moseley Braun, the first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, rushed to her desk and sought recognition from the presiding officer. Under consideration was an amendment introduced by North Carolina senator Jesse Helms to renew a patent to the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) for an insignia that featured the first national flag of the Confederate States of America.1

The UDC first obtained a congressional patent for its insignia in 1898. A small number of such patents had been granted to a group of organizations considered to be civic or patriotic, such as the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic and the American Legion. The patents expired after 14 years, unless renewed, and the UDC’s patent had been routinely renewed throughout the 20th century. The latest renewal effort had been considered in the Judiciary Committee and passed by the Senate in 1992, but it was left unfinished when the House of Representatives adjourned at the end of the session. In the spring of 1993, South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond again raised the patent issue in committee, expecting easy approval, but the composition of the committee had changed. In the wake of the 1992 election, labeled the “Year of the Woman” by the press, two women now sat on the Judiciary Committee, including Illinois freshman Carol Moseley Braun.2

On May 6, 1993, the patent renewal came before the committee for a vote. Moseley Braun looked at it and said, “I am not going to vote for that.” Challenging Thurmond and his allies, Mosely Braun stated that she did not oppose the existence of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, nor did she object to their ability to use the flag. If the UDC sought a congressional imprimatur for that insignia, however, Moseley Braun insisted that “those of us whose ancestors fought on a different side of the conflict or were held as human chattel under the flag of the Confederacy have no choice but to honor our ancestors by asking whether such action is appropriate.” Moseley Braun proved to be persuasive, and the committee voted 12 to 3 against renewal. She thought the debate had ended, but when Senator Helms appeared in the Chamber on July 22 to seek approval of an amendment that would renew the UDC patent, the battle began again.3

“Mr. President,” Helms began, “the pending amendment … has to do with an action taken by the Senate Judiciary Committee on May 6…. This action was, I am sure, an unintended rebuke unfairly aimed at about 24,000 ladies who belong to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, most of them elderly, all of them gentle souls.” Briefly summarizing the many charitable efforts of the UDC, Helms noted that since 1898, “Congress has granted patent protection for the identifying insignia and badges of various patriotic organizations,” including the UDC. Renewing the patent, he insisted, was not an effort “to refight battles long since lost, but to preserve the memory of courageous men who fought and died for the cause they believed in.”4

Sitting in a committee hearing, Moseley Braun was surprised to hear of Helms’s efforts on behalf of the UDC. She rushed to the mostly empty Chamber—only three senators had been present when Helms introduced his amendment—and began an impromptu speech. Stating that Helms was attempting to undo the work of the Judiciary Committee, Moseley Braun again laid out her objections. “To give a design patent,” a rare honor “that even our own flag does not enjoy, to a symbol of the Confederacy,” she argued, “seems to me just to create the kind of divisions in our society that are counterproductive…. Symbols are important. They speak volumes.” Helms, Thurmond, and their allies dismissed her objections, noting the important work done by the UDC, especially the organization’s aid to veterans of all wars, but Moseley Braun refused to back down. “It seems to me the time has long passed when we could put behind us the debates and arguments that have raged since the Civil War, that we get beyond the separateness and we get beyond the divisions.” Thinking she had put forth a convincing argument, Moseley Braun introduced a motion to table the Helms amendment, which would effectively block its passage.5

As a vote was called on her motion to table the amendment, senators strolled into the Chamber for what they thought was a routine vote on an inconsequential issue. One senator later admitted that he “didn’t have the slightest idea what this was about.” As the roll call continued, it became clear that most senators were voting along party lines. With her party in the majority, Democrat Moseley Braun should have been well placed for success, but nearly all southern senators, regardless of party affiliation, supported Helms. The final tally was 48 to 52 against, and Moseley Braun’s motion to table the amendment went down to defeat.

Stunned, Moseley Braun again sought recognition. As she gained the floor a second time, her voice betrayed a sense of urgency. “I have to tell you this vote is about race,” she declared. “It is about racial symbols … and the single most painful episode in American History.” Earlier, she had “just kind of held forth and quietly thought [she] could defeat the motion,” Moseley Braun recalled in an oral history interview. When the motion was defeated, however, her reaction was, “Whoa! Wait a minute. This cannot be!” Insisting on holding the floor and yielding only for questions, Moseley Braun warned her colleagues, “If I have to stand here until this room freezes over, I am not going to see this amendment put on this legislation.”6

Realizing that many of her colleagues had cast their vote with little knowledge of the actual content of the amendment, Moseley Braun explained why she believed this vote was important. To those who thought the amendment was “no big deal,” she explained that this was “a very big deal indeed.” Approval of this Confederate symbol would send a signal “that the peculiar institution [of slavery] has not been put to bed for once and for all.” As Moseley Braun continued her unplanned filibuster, senators began to listen. Several commented that they hadn’t understood the full meaning of the amendment and regretted their vote. Nebraska senator James Exon summed it up: “The Senate has made a mistake.” But the motion to table had failed. What could be done?7

What followed was a dramatic turn of events. Over the course of a three-hour debate, senators began calling for reconsideration of Moseley Braun’s motion. The pivotal moment came when Alabama senator Howell Heflin took the floor. “I rise with a conflict that is deeply rooted in many aspects of controversy,” he began. “I come from a family background that is deeply rooted in the Confederacy.” Heflin spoke of his deep respect for his ancestors and for the charitable work of the Daughters of the Confederacy, but he acknowledged the changing times. “The whole matter boils down to what Senator Moseley Braun contends,” he concluded, “that it is an issue of symbolism. We must get racism behind us, and we must move forward. Therefore, I will support a reconsideration of this motion.” With Heflin leading the way, others followed.8

Introduced by Senator Robert Bennett of Utah, a motion to reconsider gave senators a second chance to vote. When the roll call ended, 76 senators supported Moseley Braun. She had convinced 28 senators, including 10 from formerly Confederate states, to change their vote. With that motion passed, Moseley Braun’s motion to table the amendment again came before the Senate, passing by a vote of 75 to 25. Helms’s amendment was tabled and did not appear in the bill. Moseley Braun thanked her colleagues “for having the heart, having the intellect, having the mind and the will to turn around what, in [her] mind, would have been a tragic mistake.”9

Rare are the moments in Senate history when a single senator has changed the course of a vote. In this case, the presence of an African American woman, who was the only Black member of the Senate, altered the debate. That fact was readily acknowledged. “If ever there was proof of the value of diversity,” commented California senator Barbara Boxer, “we have it here today.” Ohio senator Howard Metzenbaum agreed. “I saw one person, who was able to make a difference, stand up and fight for what she believes in” and “she showed us today how one person can change the position of this body.” 10

Notes

1. “On Race, a Freshman Takes the Helm,” Boston Globe, July 25, 1993, 69.

2. “Confederate Flag Raises Senate Flap,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 6, 1933, 1A; “A Symbolic Victory for Moseley-Braun,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1933, D3; “Confederate Symbol Causes Controversy,” New York Times, May 10, 1993, D2; “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate,” New York Times, July 23, 1993, B6. The insignia was last renewed on November 11, 1977, by Public Law 95-168 (95th Cong.).

3. Congressional Record, 103rd Cong., 1st sess., July 22, 1993, 16682; “Moseley-Braun opposes Confederate Group on Insignia,” Chicago Tribune, May 4, 1933, D7; “Daughters of Confederacy’s Insignia Divides Senate Judiciary Committee,” Wall Street Journal, May 6, 1933, A12; “Braun Leads Fight Against Confederate Logo,” Chicago Defender, May 11, 1933, 8.

4. Congressional Record, 16676. The Record reflects Helms’s slight revisions to his statement.

5. Congressional Record, 16678, 16681.

6. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; “Freshman Turns Senate Scarlet,” Washington Post, July 27, 1993, A2; "Carol Moseley Braun: U.S. Senator, 1993–1999," Oral History Interviews, January 27 to June 16, 1999, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C., 18; Congressional Record, 16681, 16683.

7. Congressional Record, 16683, 16684.

8. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; Congressional Record, 16687–88.

9. Congressional Record, 16693–94.

10. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; “Moseley-Braun Molds Senate’s Outlook on Racism,” Austin American Statesman, July 24, 1993, A17; Congressional Record, 16691.

|

| 202202 02Celebrating Black History Month

February 02, 2022

To celebrate Black History Month, the Senate Historical Office presents stories, profiles, and interviews available on Senate.gov that recognize the many contributions of African Americans to the U.S. Senate and the integral role they have played in Senate history.

To celebrate Black History Month, the Senate Historical Office presents stories, profiles, and interviews available on Senate.gov that recognize the many contributions of African Americans to the U.S. Senate and the integral role they have played in Senate history.

Shortly after the Civil War, Hiram R. Revels (1870) and Blanche K. Bruce (1875) of Mississippi set historic milestones as the first African Americans to be elected to the Senate. It would be nearly another century—not until 1967—before Edward W. Brooke of Massachusetts followed in their historic footsteps. In 1993 Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois became the first African American woman to be elected to the Senate. To date, 11 African Americans have served as U.S. senators. In 2021 California senator Kamala D. Harris resigned her Senate seat and took the oath of office as the nation’s 49th vice president, thereby becoming the first African American to serve as the president of the Senate.

The role of African Americans in Senate history extends beyond those who served in elected office. One of their earliest and most enduring contributions came with the construction of the U.S. Capitol. Although historians know little about the laborers who built the Capitol, evidence shows that much of that labor force was African American, both free and enslaved. Many years later, Philip Reid, an enslaved man, brought to the Capitol the mechanical expertise needed to separate and then cast the individual sections of the Statue of Freedom, which was placed atop the Capitol Dome in 1863.

African Americans also worked in and around the Senate Chamber in the 19th century. Tobias Simpson, for example, was a messenger from 1808 to 1825. His quick action during the British attack on the Capitol in 1814 saved valuable Senate records, and he was subsequently honored with a resolution (and a pay bonus). His role in that record-saving endeavor was described in an 1836 letter written by Senate clerk Lewis Machen. Another example was a young African American boy named William Hill. In the winter of 1820, senators counted on the warmth provided by fires tended by Hill, who was paid $37 for his services by Sergeant at Arms Mountjoy Bayly.

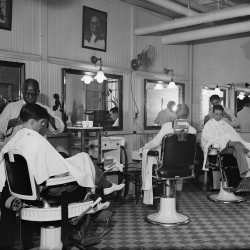

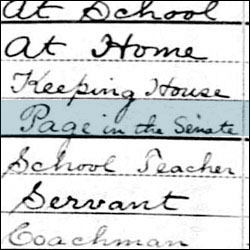

Several African Americans employed by the Senate became trailblazers. In 1868 Senate employee Kate Brown sued a railroad company that forcibly removed her from a train after she refused to sit in the car designated for Black passengers. Brown’s case eventually made it to the Supreme Court, which ruled in Brown’s favor in 1873. The first African American to join the Senate’s historic page program, Andrew F. Slade, was appointed in 1869 and served until 1881. John Sims, known by his contemporaries as the “Bishop of the Senate,” built relationships with senators in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as both a Senate barber and a popular Washington, D.C., preacher.

The first African Americans to be hired for professional clerical positions appeared in the early 20th century, including Robert Ogle, a messenger and clerk for the Senate Appropriations Committee, and Jesse Nichols, who served as government documents clerk for the Senate Finance Committee from 1937 to 1971. Senate staff members Thomas Thornton and Christine McCreary and news correspondent Louis Lautier challenged the de facto segregation of Capitol Hill in the 1940s, '50s and '60s. In 1985 Trudi Morrison became the first woman and the first African American to serve as deputy sergeant at arms of the Senate. Alfonso E. Lenhardt, who served as sergeant at arms from 2001 to 2003, was the first African American to hold that post. The Senate appointed Dr. Barry C. Black as Senate chaplain on July 7, 2003, another first for African Americans. On March 1, 2021, Sonceria Ann Berry became the first African American to serve as secretary of the Senate.

These are just a few milestones among many. As research continues, Senate historians are discovering other stories of African Americans who have played a unique and integral role in Senate history.

|

| 202106 01Shaving and Saving: The Story of Bishop Sims

June 01, 2021

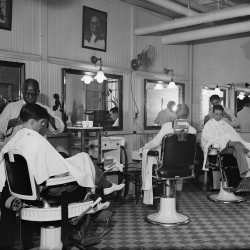

As a child, having been born into slavery in 1843, John Sims was forced to train the bloodhounds his master used to track runaway slaves. When the Civil War began in 1861, the teenaged Sims escaped bondage and fled north. When he died 73 years later, Sims was a beloved and well-known figure on Capitol Hill, a friend and confidant of some of the most powerful men in Washington. He is largely forgotten today, because John Sims wasn’t a powerful senator or a high-profile member of Capitol Hill staff—he was the Senate’s barber.

As a child, having been born into slavery in 1843, John Sims was forced to train the bloodhounds his master used to track runaway slaves. When the Civil War began in 1861, the teenaged Sims escaped bondage in his native South Carolina and fled north. When he died 73 years later, Sims was a beloved and well-known figure on Capitol Hill, a friend and confidant of some of the most powerful men in Washington. Despite his impressive rise from the bonds of slavery to the corridors of power, he is largely forgotten today. That’s because John Sims wasn’t a powerful senator or a high-profile member of Capitol Hill staff—he was the Senate’s barber.1

Sims’s dangerous flight to freedom landed him in the town of Oskaloosa in southeast Iowa. He arrived with no funds and no marketable skills, but he managed to find work in a barbershop. An apprenticeship followed and soon he was earning a living as a skilled barber. Then, in the mid-1880s, came the first of two fateful senatorial encounters—when Iowa senator William Boyd Allison got a haircut.

Throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th century, many Senate jobs were filled through patronage. Senator Allison, who chaired the Appropriations Committee, had plenty of patronage to give. He brought Sims to the Senate, where the barber’s tonsorial talents gained recognition. Sims “knows the whims [and] the vanities” of the Senate, reported the New York Times. His skill with shears and razor kept him employed long after his patron was gone, but it was Sims’s weekend job and a second notable encounter that brought him to public attention.2

John Sims moonlighted as a preacher at the Universal Church of Holiness in Washington, D.C. One day in 1916, Ohio senator (and future president) Warren G. Harding sat in the barber’s chair. “Sims,” he said, “I’m coming down next Sunday to hear you preach.” A few days later, to the surprise of the entirely African American congregation, Senator Harding attended the service. “He walked in by himself,” Sims recalled, “and took a seat near the middle of the church and waited until I was through.” When the service ended, Harding thanked Sims and returned to the Capitol to spread the news of the preaching talents of the Senate barber.

A week later, Harding returned to the Universal Church of Holiness and brought several of his colleagues with him. As the years passed, more and more senators appeared. Vice Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Charles Dawes also attended. “From the North, from the South, from the East and the West they have come to hear me,” Sims explained. “And to think that I have come up from a lowly place of humility . . . to where I have the honor of preaching to those who are high in the nation’s affairs!” Sims insisted that he owed it all to Harding. “He started it all—and the Senators have been coming to hear me ever since.”

The preaching barber became known as the “Bishop of the Senate.” His prayers, noteworthy for both length and fervor, also enlivened his official Senate duties. “[If] he thought the occasion required [it],” commented a reporter, Sims would “drop to his knees . . . in the midst of . . . a shave and pray with all his heart” for the senator sitting in his chair. In 1921, as the Senate prepared to vote for its next official chaplain, Senator Bert Fernald of Maine asked, “Can we vote for anybody who has not been placed in nomination?” With an affirmative answer to his question, he cast his vote for John Sims, although the post went to the Reverend Joseph J. Muir.3

Bishop Sims was strictly nonpartisan and loyally supported all of his patrons at election time. When two of his favorite Senate clients—Democrat Joseph T. Robinson of Arkansas and Kansas Republican Charles Curtis—competed for the vice presidency in 1928, Sims fervently prayed for each to win their party’s nomination. His prayers were answered. The two men faced each other in the general election. “Who are you for [now],” Robinson asked the barber, “myself or Senator Curtis?” “I prayed for your nominations,” Sims replied diplomatically, but now “you gotta hustle for yourself.”

John Sims achieved success, as barber and as preacher, but one cherished goal remained elusive—to pray in an open session of the Senate. “Sims cannot die happy unless he has had at least one chance to shrive the Senate,” reported the Baltimore Sun in 1928. “For many years he has been longing to be allowed to open one of the Senate sessions with a prayer.” That year, it looked as if the 85-year-old preacher’s wish would finally come true. With the second session of the 70th Congress set to convene in December, a senator pledged to invite him to give the daily prayer, but no record of such an occasion has been found. It seems that wish remained unfulfilled.4