| 202502 26Reconstruction Louisiana and the Case of PBS Pinchback

February 26, 2025

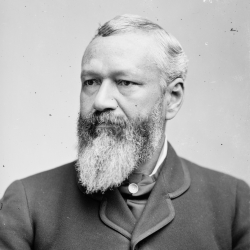

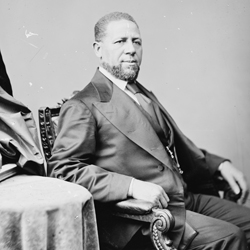

In February 1870, Hiram Revels of Mississippi made history as the first Black American to be elected to the United States Senate. Revels served only 13 months, but five years later the Mississippi legislature, still under the control of Republicans who were swept into office as part of post-Civil War Reconstruction, elected Blanche K. Bruce, making him the first Black American elected to a full Senate term. Often forgotten, however, is another pioneering Black politician, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback of Louisiana, who was elected to the Senate in 1873 but never allowed to take his seat.

In February 1870, Hiram Revels of Mississippi made history as the first Black American to be elected to the United States Senate. Revels served only 13 months, but five years later the Mississippi legislature, still under the control of Republicans who were swept into office as part of post-Civil War Reconstruction, elected Blanche K. Bruce, making him the first Black American elected to a full Senate term. Often forgotten, however, is another pioneering Black politician, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback of Louisiana, who was elected to the Senate in 1873 but never allowed to take his seat.

Pinchback’s story offers a window into an era of political upheaval in the United States, when Black Americans fought to exercise their newly won political and civil rights in the South, and former Confederates sought, often violently, to reclaim power from Republican-dominated Reconstruction governments in which a large number of African Americans held office. Throughout the 1870s, members of the Senate and House of Representatives debated the power of Congress to ensure fair elections in the South and enforce protections enshrined in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.1

Pinchback, who went by the initials PBS but was “Pinch” to his friends, was born in 1837 to a formerly enslaved mother, Eliza Stewart, and her white enslaver, Major William Pinchback. Major Pinchback had freed and married Stewart and moved the family to Mississippi. When Major Pinchback died in 1848, Stewart, denied the Pinchback estate by Mississippi courts and fearing re-enslavement by Major Pinchback's family, moved with her children to Cincinnati, Ohio, where PBS Pinchback was already attending boarding school. At 12 years old, Pinchback ended his formal education and went to work on Mississippi river boats, eventually falling in with a gambler who instructed him in the art of dice and card games.2

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Pinchback made his way to Union-occupied New Orleans where he enlisted with the Union army. He was tasked by General Benjamin Butler with recruiting a company of Black soldiers and was commissioned as the company’s captain. He resigned in September 1863 after enduring poor treatment from white troops and officers. A gifted orator, Pinchback went north after the war to promote Black suffrage in the South and later settled in Alabama to help freedmen organize for their political rights.3

After the Radical Republicans in Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act in 1867 to remove former Confederates from power and protect Black rights, Pinchback returned to New Orleans to work with Republican officials in the city. A speech he delivered at the Republican state party convention in defense of Black civil rights led to Pinchback’s appointment to the party’s executive committee, followed by his election to the state constitutional convention in 1867. When the constitutional convention first met in 1866, a white mob had disrupted the proceedings and sparked what came to be known as the Mechanics Institute Massacre (the Institute was being used as the State House at the time), which left 46 African Americans dead and another 60 injured. At the 1867 constitutional convention, undeterred by the threat of violence, Pinchback led the drafting of a civil rights article for the new constitution that granted Blacks the right to vote and disenfranchised former Confederates.4

Impressed with his performance at the convention, Louisiana Republicans floated Pinchback as the party’s nominee for governor, but he demurred and supported a young white attorney from Illinois, Henry Clay Warmoth, who won election in April 1868 along with other Radical Republicans, despite widespread violence and intimidation against Black voters. Meanwhile, Pinchback won election to the state senate, but only after a state committee on elections determined there had been fraud in the balloting and awarded him the seat.5

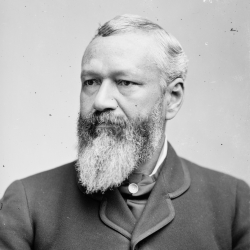

In the years that followed, Republicans in Louisiana and Washington split into contending factions over the future of Reconstruction, forcing Pinchback to negotiate a rapidly shifting political landscape. The state’s Black Republicans grew frustrated with Governor Warmoth as he failed to support strong civil rights legislation and curried favor with white Democrats by, among other things, appointing former Confederates to state office. Pinchback initially continued to support Warmoth and was rewarded with election as president of the Senate, a post that carried with it duties as acting lieutenant governor. But in 1872, when Warmoth announced his support for presidential candidate Horace Greeley, a Democrat backed by the new Liberal Republican Party who came to oppose Radical Reconstruction in favor of reconciliation with former Confederates, Pinchback broke with his political patron. Back in the good graces of the state’s regular Republicans, Pinchback campaigned for President Ulysses S. Grant and for continued federal support for Black civil rights in the South. In the race for Louisiana governor, Pinchback stumped for U.S. Senator William Pitt Kellogg against Democrat John McEnery, who ran with the support of Warmoth and the state’s Liberal Republicans.6

The 1872 elections left Louisiana in political chaos. McEnery and his coalition of Democrats and Liberal Republicans declared themselves the victors, while the state’s Republicans charged that they would have won if not for widespread fraud and violence against Black voters. When Governor Warmoth took control of the state’s election board to certify the Democratic victory in violation of a federal court order, the district judge intervened, and federal troops took control of the State House. On December 9, 1872, the Republicans passed articles of impeachment against Warmoth, which under Louisiana law suspended him from office pending trial. As a result, Pinchback became the acting governor, the first Black governor of a state in the nation’s history. When the newly elected government was to meet on January 14, both sides organized rival governments, each claiming to be the legitimate representatives of the people. Backed by the federal courts, the Republicans gathered in the State House and inaugurated Kellogg as governor, while the Democrats organized their own legislature at City Hall and swore in McEnery.7

Louisiana’s political troubles soon reached the U.S. Senate, with Pinchback at the center. When Kellogg resigned his Senate seat to take over as governor, the competing legislatures each elected a replacement to complete the final weeks of Kellogg’s term. Both Democrat William McMillen and Republican John Ray presented their credentials—one signed by McEnery and the other by Kellogg, respectively—to the Senate. At the same time, the Republican legislature elected Pinchback to the Senate for the full term beginning on March 4, 1873, and the Democratic coalition legislature elected McMillen for the seat.

A Senate increasingly divided over Reconstruction policies and the role of the federal government in enforcing Black political rights in the South took up the question of who held rightful claim to Louisiana’s Senate seat. The Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, chaired by Radical Republican leader Oliver Morton of Indiana, launched an investigation into “whether there is any existing State government in Louisiana” that could name a senator. After a month of examination, the committee recommended rejecting both sets of credentials and offered a bill to mandate new elections in the state. A committee majority—which included Republicans Matthew Carpenter of Wisconsin, John Logan of Illinois, James Alcorn of Mississippi, and Henry Anthony of Rhode Island—concluded that if the election had “been fairly conducted and returned, Kellogg … and a legislature composed of the same political party, would have been elected,” and that recognizing the McEnery government without scrutinizing the election returns “would be recognizing a government based upon fraud, in defiance of the wishes and intention of the voters of that State.” But the majority also charged that the Republican legislature in Louisiana had no legal authority, strongly condemned the intervention of the federal courts, and concluded that the Republicans had “usurped” the government by tossing out the Democratic victory. In the minority, Democrats on the committee called for McMillen to be seated, arguing that Congress had no role to play in state elections and could not throw out the Democrats’ “official” results. Only Chairman Morton made the case that the Republicans were entitled to the seat unconditionally. The full Senate took no action, however, and the seat remained vacant.8

When new senators were sworn in at the start of the 43rd Congress on March 4, 1873, the Senate did not address the Louisiana seat. That spring, white paramilitary groups continued a campaign of violence against Black Louisianans, including the infamous Colfax Massacre in April when 80 to 100 African Americans were killed. Despite the ongoing political violence, a growing number of senators began to question federal intervention in the South. When the Senate convened for the first regular session in December 1873, the Committee on Privileges and Elections took up Pinchback’s case but reported that they were “evenly divided” and “beg[ed] leave to be discharged from further consideration.” Pinchback faced yet another setback in January 1874 when his champion in the Senate, Oliver Morton, heard rumors that Pinchback had secured his election through bribes and wavered in his commitment to the case. When Morton moved for a new investigation into Pinchback’s personal conduct by the Committee on Privileges and Elections, Matthew Carpenter instead introduced a resolution calling for new elections in Louisiana. Neither resolution was put to a vote, the case languished for the remainder of 1874, and the seat remained vacant.9

Pinchback’s case received new life in January 1875 when, after another contested election in 1874, Louisiana’s Republican legislature again elected him to the Senate “in order that all doubts or questioning of the title … be entirely silenced.” Morton set his qualms aside and threw himself once again behind securing Pinchback his seat. Senate Democrats refused to concede the fight and launched a filibuster that kept the Senate in session all night on February 17. They had the support of a number of Republicans, such as George Edmunds of Vermont, who had become highly critical of Reconstruction policy and the federal government’s role in supporting Black voters in the South. The debate continued on and off for weeks, with Republicans railing against the frauds and intimidation that had allowed McEnery and the Democrats to claim victory in the 1872 elections, and Democrats dismissing Kellogg as a “usurper.” By the end of the session, Republicans had still failed to get a vote on the Pinchback resolution.10

Meanwhile, in December 1874, responding to a plea from President Grant, the House of Representatives had created a committee to investigate Louisiana’s 1874 elections and resolve the political deadlock. New York Representative and future Vice President William Wheeler produced a plan, later known as the Wheeler Compromise, whereby the Democrats would accept Kellogg’s position as governor and be granted a majority of seats in the state assembly, and the Republicans would be given control of the state senate. Kellogg and both parties accepted the plan in April 1875, and in January 1876 this newly constituted Louisiana legislature declared the Senate seat vacant and elected a new senator, James B. Eustis, a Democrat. A trio of Republican Louisiana state senators submitted a statement to the Senate lamenting “being unable … to elect a gentleman strictly of our own party faith” but defending Eustis’s election as “an act in the interests of peace and prosperity, and a healthy and lasting good-will among all here at home.” This willingness by Republicans to compromise at the expense of Black voters signaled the beginning of the end of Reconstruction in Louisiana.11

Morton refused to accept that the Louisiana seat was vacant for Eustis to claim and in February 1876 put Pinchback’s case before the Senate one last time. Blanche Bruce of Mississippi, who had entered the Senate the previous year, used the occasion to deliver his maiden speech. Bruce told his Republican colleagues that to reject Pinchback amounted to the federal government turning its back on Louisiana and its Black citizens. In a closed executive session, Bruce was even more forceful. “If when the Louisiana case is again called, it be not settled,” he stated, “I will resign my seat in a body which presents this spectacle of asinine conduct.”12

The Senate did settle the case, and Bruce did not resign. On March 8, 1876, more than three years after Pinchback had arrived in Washington to take the oath of office, the Senate rejected his claim to the seat. Seated at the back of the Chamber while the final debate and vote took place, Pinchback reportedly “acted as one relieved, and who felt the great strain was over.” As a consolation, the Senate awarded him $16,000, approximately what he would have earned as a senator during those three years.13

Pinchback returned to New Orleans where he remained an important political figure for a time, even as Democratic lawmakers consolidated their power in the former Confederate states under Jim Crow laws. In a letter to Blanche Bruce, he called himself “the liveliest corpse in the dead South.” Pinchback settled back in Washington in the 1890s and remained a presence at banquets and parties but increasingly seemed a relic of a bygone political era, when Black southerners had won election to federal office. Pinchback died in 1921 at the age of 84. After Blanche K. Bruce left the Senate in 1881, more than 80 years passed before another African American—Edward Brooke of Massachusetts—won election to the Senate.14

Notes

1. History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, Office of the Historian, Black Americans in Congress, 1870–2007, “’The Fifteenth Amendment in Flesh and Blood:’ 1870–1901,” accessed February 18, 2025, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Essays/Fifteenth-Amendment/Introduction/.

2. Philip Dray, Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction Through the Lives of the First Black Congressmen (Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 103; George H. Devol, Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi, (Home Book Co., 1894), 216–17.

3. Charles Vincent, Black Legislators in Louisiana During Reconstruction (Southern Illinois University Press, 2011), 8–10; James Haskins, The First Black Governor: Pinkney Benton Stewart Pinchback (MacMillan, 1973; African World Press, 1996), 24–25, 38–45.

4. Haskins, First Black Governor, 47–54, 56–60; Dray, Capitol Men, 28–32, 106.

5. Dray, Capitol Men, 107.

6. Dray, Capitol Men, 109–110, 117–118, 124–127; Haskins, First Black Governor, 82–83, 100–102; “New Orleans,” New York Times, January 21, 1872, 1.

7. Dray, Capitol Men, 134. For the most complete details of the events surrounding the elections, see Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Louisiana Investigation, S. Rpt. 457, 42nd Cong., 3rd sess., February 20, 1873.

8. S. Rpt. 457, XLIV.

9. Congressional Record, 43rd Cong., 1st sess., December 15, 1873, 188; January 30, 1874, 1036–58; March 3, 1874, 1926–27; Haskins, First Black Governor, 196–99, 202–4; Dray, Capitol Men, 224–25. In the meantime, Pinchback had been on the ballot for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1872, but the election was contested and remained unresolved for much of the 43rd Congress. He pleaded his case to the House of Representatives in June 1874 to obtain the at-large seat, but the House awarded the seat to his Democratic opponent.

10. “In Louisiana,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 13, 1875, 1; Resolution that Senate recognize validity of credentials of P. B. S. Pinchback, S. Mis. Doc. 16, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., December 23, 1874; Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Credentials of P. B. S. Pinchback, for seat in Senate from Louisiana, S. Rpt. 626, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., February 8, 1875.

11. James T. Otten, “The Wheeler Adjustment in Louisiana: National Republicans Begin to Reappraise Their Reconstruction Policy,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 13, no. 4 (1972): 349–67; Views of certain State senators on election of Hon. J. B. Eustis as United States Senator from Louisiana, S. Mis. Doc. 41, 44th Cong, 1st sess., January 26, 1876.

12. New Orleans Times, February 17, 1876, quoted in Sadie Daniel St. Clair, The National Career of Blanche Kelso Bruce (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1947), 96–97.

13. Congressional Record, 44th Cong., 1st sess., March 8, 1876, 1557–58; New Orleans Republican, March 14, 1876, quoted in Haskins, 221; Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Question of allowance proper to be made to P. B. S. Pinchback, late contestant for seat in Senate from Louisiana, S. Rpt. 274, 44th Cong., 1st sess., April 17, 1876.

14. Haskins, First Black Governor, 241; “Pinchback, Louisiana Governor in 1872, Dead,” Washington Post, December 22, 1921, 10.

|

| 202312 11In Form and Spirit: Creating the Statue of Freedom

December 11, 2023

The massive bronze Statue of Freedom has been perched atop the great dome of the United States Capitol since its assembly was completed on December 2, 1863, amidst the pall of civil war. As the crowning feature of the building’s new cast-iron dome, it offered a glimmer of hope that the nation would endure. The continuation of the construction of the dome had served as a symbolic backdrop during the dark war years, but Freedom’s journey to the top of the dome had begun years before.

The massive bronze Statue of Freedom has been perched atop the great dome of the United States Capitol since its assembly was completed on December 2, 1863, amidst the pall of civil war. As the crowning feature of the building’s new cast-iron dome, it offered a glimmer of hope that the nation would endure. The continuation of the construction of the dome had served as a symbolic backdrop during the dark war years, but Freedom’s journey to the top of the dome had begun years before.

The Capitol underwent a major transformation during the Civil War. On March 4, 1861, with war looming, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his first inaugural address in the shadow of the half-finished dome. The building was in the midst of a major expansion project that had begun 10 years earlier and included the construction of two large wings and a new, taller dome. At the onset of the war, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, the superintendent of the Capitol extension and dome construction, observed that the government had “no money to spend except in self defense” and issued the order to stop working. Despite this order, the iron foundry hired to construct the dome, Janes, Fowler and Kirtland, continued the project without pay. The foundry worried that the cast iron materials already procured would be damaged or destroyed if installation was delayed.1

Members of Congress, many of whom shared similar concerns, debated a resolution to restore funding in the spring of 1862. “Every consideration of economy, every consideration of protection to this building, every consideration of expediency requires that it should be completed, and that it should be done now,” Vermont senator Solomon Foot appealed to his fellow senators. “To let these works remain in their present condition is, in my judgment, to say the least of it, the most inexcusable, needless, and extravagant waste and destruction of property,” he argued. “We are strong enough yet, thank God, to put down this rebellion and to put up this our Capitol at the same time.” Congress restored construction funding in April 1862, and the foundry’s dome contract was renewed. Slowly and steadily, the massive dome became a reality during those difficult war years. The vision of this continuing endeavor provided inspiration during this perilous time. “If people see the Capitol going on, it is a sign we intend the Union shall go on,” remarked President Abraham Lincoln. “War or no war, the work goes steadily on,” reported the Chicago Tribune.2

To crown the new dome, Architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter, who designed the cast-iron structure, called for a large statue, which he originally conceived as an allegorical figure “holding a liberty cap”—a cloth cap worn by the formerly enslaved in Ancient Greece and Rome that later became a popular symbol of the American and French Revolutions. In 1855 Meigs asked American sculptor Thomas Crawford, who had produced other sculptural pieces for the Capitol project, to create a representation of Liberty for the dome’s statue. Working in his studio in Rome, Crawford instead proposed a figure representing “Freedom triumphant in War and Peace.” His first design, a female holding an olive branch in one hand and a sword in the other, was made before he realized that the sculpture needed more height and a taller pedestal. His second sketch, which Crawford said represented “Armed Liberty,” was a female figure in classical dress wearing a liberty cap adorned with stars and holding a shield and wreath in one hand and a sword in the other.3

Upon receiving Crawford’s second design, Meigs rightly anticipated that his superior, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, a Southern enslaver (and future president of the Confederacy) who oversaw the Capitol construction project, would object to the inclusion of the liberty cap. “Mr. Crawford has made a light and beautiful figure of Liberty…. It has upon it the inevitable liberty cap, to which Mr. Davis will, I do not doubt, object,” Meigs recorded in his journal. Indeed, Davis did object. “History renders [the liberty cap] inappropriate to a people who were born free and would not be enslaved,” Davis argued, willfully ignoring the millions of enslaved people who toiled across the nation. “[S]hould not armed Liberty wear a helmet?” Davis offered. Crawford’s third and final design reflected Davis’s suggestion. Freedom was clad with a helmet, "the crest of which is composed of an eagle’s head and a bold arrangement of feathers, suggested by the costume of our Indian tribes," Crawford explained.4

Once the statue design was approved, Crawford prepared a plaster model in his studio, his last work before he fell ill and died in 1857. Divided into five separate pieces, the model was shipped to America. After a long and arduous journey in a ship plagued by leaks, all of the pieces finally arrived in Washington in March 1859. An Italian craftsman working in the Capitol reassembled the model, covering all the seams with fresh plaster, and it was temporarily displayed in the old House Chamber (now known as Statuary Hall). Clark Mills, the owner of a local iron foundry, was hired to cast the statue in bronze in 1860. When the time came to disassemble the plaster model for casting, the Italian craftsman demanded additional pay from Mills, claiming that he alone knew how to separate the model. Mills turned instead to one of his foundry workers, an enslaved African American artisan named Philip Reid, who skillfully devised a method of separating the plaster model so that the individual sections could be cast and the bronze statue assembled. Reid labored seven days a week on Freedom, the only worker in Mills’s foundry paid to attend to the statue on Sundays, according to government records. Reid's rate of pay was $1.25 per day; however, as an enslaved man, he was likely only permitted to keep his Sunday earnings. While Reid was one of many enslaved people who helped to build the Capitol, he is unique in that his name has been documented in official records. “Philip Reid’s story is one of the great ironies in the Capitol’s history,” architectural historian of the Capitol William C. Allen observed, “a workman helping to cast a noble allegorical representation of American freedom when he himself was not free.”5

More ironic yet was the fact that when the statue was finally placed atop the dome on December 2, 1863, Reid was a free man, liberated by the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act in 1862 . Reporting from Washington that December day, a correspondent for the New York Tribune recounted Reid’s central role in the creation of Freedom, and reflected, “Was there a prophecy in that moment when the slave became the artist, and with rare poetic justice, reconstructed the beautiful symbol of freedom for America?” The installation of the Statue of Freedom proved to be symbolic, signifying the enduring nation in a time of civil war. A solemn ceremony marked completion of the dome and the placement of Freedom. The “flag of the nation was hoisted to the apex of the dome,” wrote an observer, “a signal that the ‘crowning’ had been successfully completed.” A salute was ordered to commemorate the event, “as an expression…of respect for the material symbol of the principle upon which our government is based.” The 12 forts that guarded the capital city answered with cannon fire when artillery fired a 35-gun-salute—one gun for each state, including those of the Confederacy.6

“Freedom now stands on the Dome of the Capitol of the United States,” wrote the Commissioner of Public Buildings, Benjamin Brown French, in his journal; “May she stand there forever, not only in form, but in spirit.” It was an appropriate finale to a year that began with Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. “Let us indulge the hope that our posterity to the end of time may look upon it with the same admiration which we do today,” one observer wrote of Freedom that December day, “and an unbroken Union three years since would have viewed this glorious symbol of patriotism and achievement of art.” Indeed, the nation emerged from the Civil War damaged but intact, improved by the permanent emancipation of four million African Americans in December 1865. 7

Notes

1. William C. Allen, The Dome of the United States Capitol: An Architectural History (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1992), 55.

2. Congressional Globe, 37th Cong., 2nd sess., March 25, 1862, 1349; Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, eds., Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 147; “The Capitol Improvements,” Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1863, 1.

3. “Statue of Freedom,” Architect of the Capitol, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/statue-freedom; "The Liberty Cap in the Art of the U.S. Capitol," Architect of the Capitol, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/blog/liberty-cap-art-us-capitol; William C. Allen, History of the United States Capitol: A Chronicle of Design, Construction, and Politics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 246; Allen, Dome, 42.

4. Wendy Wolff, ed., Capitol Builder: The Shorthand Journal of Montgomery C. Meigs, 1853–1859, 1861 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2001), 332; Allen, Dome, 42–43.

5. Allen, Dome, 42–43; John Philip Colletta, "Clark Mills and His Enslaved Assistant, Philip Reed: The Collaboration that Culminated in Freedom," Capitol Dome 57, (Spring/Summer 2020): 19; "History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the United States Capitol," report prepared by William C. Allen, Architectural Historian, Office of the Architect of the Capitol, June 1, 2005, p. 16, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office.

6. “The Statue of Freedom,” correspondence of the New York Tribune, reported in the Chicago Tribune, December 14, 1863, 1; "The Statue on the Capitol Dome," National Intelligencer, December 3, 1863, 3; S. D. Wyeth, The Rotunda and Dome of the US. Capitol (Washington, D.C.: Gibson Brothers, 1869), 193.

7. Benjamin Brown French, Witness to the Young Republic, A Yankee’s Journal, 1828–1870 (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1989), 439; "The Statue on the Capitol Dome," National Intelligencer, December 3, 1863, 3.

|

| 202302 02The Power of a Single Voice: Carol Moseley Braun Persuades the Senate to Reject a Confederate Symbol

February 02, 2023

On July 22, 1993, senators were considering amendments to a national service bill when suddenly, the Senate Chamber doors flew open and Illinois senator Carol Moseley Braun rushed to her desk and sought recognition. North Carolina senator Jesse Helms had proposed an amendment to renew a patent to the United Daughters of the Confederacy for an insignia that featured the first national flag of the Confederate States of America. Senator Moseley Braun, the first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, intended to stop that amendment.

July 22, 1993, began as an ordinary day as senators considered amendments to the National and Community Service Act of 1990. That routine business was suddenly interrupted, however, when the Senate Chamber doors flew open and Illinois senator Carol Moseley Braun, the first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, rushed to her desk and sought recognition from the presiding officer. Under consideration was an amendment introduced by North Carolina senator Jesse Helms to renew a patent to the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) for an insignia that featured the first national flag of the Confederate States of America.1

The UDC first obtained a congressional patent for its insignia in 1898. A small number of such patents had been granted to a group of organizations considered to be civic or patriotic, such as the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic and the American Legion. The patents expired after 14 years, unless renewed, and the UDC’s patent had been routinely renewed throughout the 20th century. The latest renewal effort had been considered in the Judiciary Committee and passed by the Senate in 1992, but it was left unfinished when the House of Representatives adjourned at the end of the session. In the spring of 1993, South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond again raised the patent issue in committee, expecting easy approval, but the composition of the committee had changed. In the wake of the 1992 election, labeled the “Year of the Woman” by the press, two women now sat on the Judiciary Committee, including Illinois freshman Carol Moseley Braun.2

On May 6, 1993, the patent renewal came before the committee for a vote. Moseley Braun looked at it and said, “I am not going to vote for that.” Challenging Thurmond and his allies, Mosely Braun stated that she did not oppose the existence of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, nor did she object to their ability to use the flag. If the UDC sought a congressional imprimatur for that insignia, however, Moseley Braun insisted that “those of us whose ancestors fought on a different side of the conflict or were held as human chattel under the flag of the Confederacy have no choice but to honor our ancestors by asking whether such action is appropriate.” Moseley Braun proved to be persuasive, and the committee voted 12 to 3 against renewal. She thought the debate had ended, but when Senator Helms appeared in the Chamber on July 22 to seek approval of an amendment that would renew the UDC patent, the battle began again.3

“Mr. President,” Helms began, “the pending amendment … has to do with an action taken by the Senate Judiciary Committee on May 6…. This action was, I am sure, an unintended rebuke unfairly aimed at about 24,000 ladies who belong to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, most of them elderly, all of them gentle souls.” Briefly summarizing the many charitable efforts of the UDC, Helms noted that since 1898, “Congress has granted patent protection for the identifying insignia and badges of various patriotic organizations,” including the UDC. Renewing the patent, he insisted, was not an effort “to refight battles long since lost, but to preserve the memory of courageous men who fought and died for the cause they believed in.”4

Sitting in a committee hearing, Moseley Braun was surprised to hear of Helms’s efforts on behalf of the UDC. She rushed to the mostly empty Chamber—only three senators had been present when Helms introduced his amendment—and began an impromptu speech. Stating that Helms was attempting to undo the work of the Judiciary Committee, Moseley Braun again laid out her objections. “To give a design patent,” a rare honor “that even our own flag does not enjoy, to a symbol of the Confederacy,” she argued, “seems to me just to create the kind of divisions in our society that are counterproductive…. Symbols are important. They speak volumes.” Helms, Thurmond, and their allies dismissed her objections, noting the important work done by the UDC, especially the organization’s aid to veterans of all wars, but Moseley Braun refused to back down. “It seems to me the time has long passed when we could put behind us the debates and arguments that have raged since the Civil War, that we get beyond the separateness and we get beyond the divisions.” Thinking she had put forth a convincing argument, Moseley Braun introduced a motion to table the Helms amendment, which would effectively block its passage.5

As a vote was called on her motion to table the amendment, senators strolled into the Chamber for what they thought was a routine vote on an inconsequential issue. One senator later admitted that he “didn’t have the slightest idea what this was about.” As the roll call continued, it became clear that most senators were voting along party lines. With her party in the majority, Democrat Moseley Braun should have been well placed for success, but nearly all southern senators, regardless of party affiliation, supported Helms. The final tally was 48 to 52 against, and Moseley Braun’s motion to table the amendment went down to defeat.

Stunned, Moseley Braun again sought recognition. As she gained the floor a second time, her voice betrayed a sense of urgency. “I have to tell you this vote is about race,” she declared. “It is about racial symbols … and the single most painful episode in American History.” Earlier, she had “just kind of held forth and quietly thought [she] could defeat the motion,” Moseley Braun recalled in an oral history interview. When the motion was defeated, however, her reaction was, “Whoa! Wait a minute. This cannot be!” Insisting on holding the floor and yielding only for questions, Moseley Braun warned her colleagues, “If I have to stand here until this room freezes over, I am not going to see this amendment put on this legislation.”6

Realizing that many of her colleagues had cast their vote with little knowledge of the actual content of the amendment, Moseley Braun explained why she believed this vote was important. To those who thought the amendment was “no big deal,” she explained that this was “a very big deal indeed.” Approval of this Confederate symbol would send a signal “that the peculiar institution [of slavery] has not been put to bed for once and for all.” As Moseley Braun continued her unplanned filibuster, senators began to listen. Several commented that they hadn’t understood the full meaning of the amendment and regretted their vote. Nebraska senator James Exon summed it up: “The Senate has made a mistake.” But the motion to table had failed. What could be done?7

What followed was a dramatic turn of events. Over the course of a three-hour debate, senators began calling for reconsideration of Moseley Braun’s motion. The pivotal moment came when Alabama senator Howell Heflin took the floor. “I rise with a conflict that is deeply rooted in many aspects of controversy,” he began. “I come from a family background that is deeply rooted in the Confederacy.” Heflin spoke of his deep respect for his ancestors and for the charitable work of the Daughters of the Confederacy, but he acknowledged the changing times. “The whole matter boils down to what Senator Moseley Braun contends,” he concluded, “that it is an issue of symbolism. We must get racism behind us, and we must move forward. Therefore, I will support a reconsideration of this motion.” With Heflin leading the way, others followed.8

Introduced by Senator Robert Bennett of Utah, a motion to reconsider gave senators a second chance to vote. When the roll call ended, 76 senators supported Moseley Braun. She had convinced 28 senators, including 10 from formerly Confederate states, to change their vote. With that motion passed, Moseley Braun’s motion to table the amendment again came before the Senate, passing by a vote of 75 to 25. Helms’s amendment was tabled and did not appear in the bill. Moseley Braun thanked her colleagues “for having the heart, having the intellect, having the mind and the will to turn around what, in [her] mind, would have been a tragic mistake.”9

Rare are the moments in Senate history when a single senator has changed the course of a vote. In this case, the presence of an African American woman, who was the only Black member of the Senate, altered the debate. That fact was readily acknowledged. “If ever there was proof of the value of diversity,” commented California senator Barbara Boxer, “we have it here today.” Ohio senator Howard Metzenbaum agreed. “I saw one person, who was able to make a difference, stand up and fight for what she believes in” and “she showed us today how one person can change the position of this body.” 10

Notes

1. “On Race, a Freshman Takes the Helm,” Boston Globe, July 25, 1993, 69.

2. “Confederate Flag Raises Senate Flap,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 6, 1933, 1A; “A Symbolic Victory for Moseley-Braun,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1933, D3; “Confederate Symbol Causes Controversy,” New York Times, May 10, 1993, D2; “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate,” New York Times, July 23, 1993, B6. The insignia was last renewed on November 11, 1977, by Public Law 95-168 (95th Cong.).

3. Congressional Record, 103rd Cong., 1st sess., July 22, 1993, 16682; “Moseley-Braun opposes Confederate Group on Insignia,” Chicago Tribune, May 4, 1933, D7; “Daughters of Confederacy’s Insignia Divides Senate Judiciary Committee,” Wall Street Journal, May 6, 1933, A12; “Braun Leads Fight Against Confederate Logo,” Chicago Defender, May 11, 1933, 8.

4. Congressional Record, 16676. The Record reflects Helms’s slight revisions to his statement.

5. Congressional Record, 16678, 16681.

6. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; “Freshman Turns Senate Scarlet,” Washington Post, July 27, 1993, A2; "Carol Moseley Braun: U.S. Senator, 1993–1999," Oral History Interviews, January 27 to June 16, 1999, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C., 18; Congressional Record, 16681, 16683.

7. Congressional Record, 16683, 16684.

8. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; Congressional Record, 16687–88.

9. Congressional Record, 16693–94.

10. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate”; “Moseley-Braun Molds Senate’s Outlook on Racism,” Austin American Statesman, July 24, 1993, A17; Congressional Record, 16691.

|

| 202005 04Charles Sumner: After the Caning

May 04, 2020

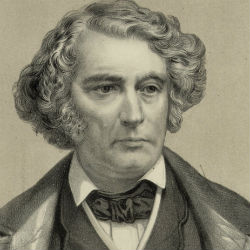

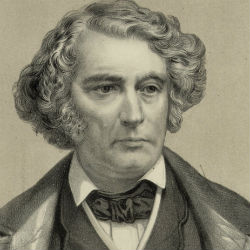

Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts is best remembered for his role in a dramatic incident in Senate history. On May 22, 1856, Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina attacked the senator at his desk in the Senate Chamber. The “Caning of Sumner” is a famous event, but of course the story did not end there. To understand the importance of Sumner’s enduring legacy as statesman and legislator, particularly in the realm of civil rights, we must explore what happened after the caning.

Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts is best remembered for his role in a dramatic and infamous event in Senate history—what has become known as the “Caning of Sumner.” Just days earlier, Sumner had delivered a fiery speech entitled “The Crime Against Kansas,” in which he railed against the institution of slavery and unleashed a stream of vitriol against the senators who defended it. In retaliation, Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina attacked Sumner at his desk in the Senate Chamber, beating him with a heavy walking stick until the senator was left bleeding and unconscious on the Chamber floor.

Sumner convalesced, returning only intermittently over the next three years. He resumed full-time duties in 1859 and over the next 15 years became a trailblazing legislator who left an indelible mark on the Senate and the country. As chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from 1861 to 1871, Sumner wielded great influence over the nation’s diplomacy, but his tireless efforts in the realm of abolition and civil rights were what truly defined his career.

Sumner was among the first members of Congress to argue that the Civil War had to be fought to end slavery as much as to save the Union. In fact, he said the two goals were inextricably linked. He called slavery “the main-spring of Rebellion” and insisted, “Let the National Government . . . simply throw the thing upon the flames madly kindled by itself, and the Rebellion will die at once.”1 He worked tirelessly behind the scenes to prevent moderate Republicans in Congress and in Abraham Lincoln’s administration from compromising on the question of abolishing slavery. When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which freed slaves in the rebelling states, Sumner praised Lincoln’s action but quickly added that the presidential proclamation did not go far enough. Only national abolition, immune from action by the Supreme Court, could guarantee an end to the heinous institution—and that meant a constitutional amendment.

To gain Senate approval of what would become the Thirteenth Amendment, Sumner collaborated with a number of antislavery activists and forged a unique alliance with members of the Women’s National Loyal League. Created by stalwart reformers Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, the Women’s National Loyal League held its first convention in May of 1863 and began a campaign to collect one million signatures on a petition demanding a constitutional amendment for the total abolition of slavery. To receive this and other petitions, Sumner asked the Senate to create a special committee “to take into consideration all propositions . . . concerning slavery.” The Senate complied and named Sumner as chairman.2

“By early 1864, the National Loyal League had collected 100,000 signatures on six thousand petition forms and mailed them to Sumner in a large trunk. On February 9, Sumner presented the petitions to the Senate. In a dramatic speech, he called the signers “a mighty army, one hundred thousand strong . . . . They ask for nothing less than universal emancipation.”3 Sumner’s speech became known as “The Prayer of One Hundred Thousand.”

Sumner hoped to use his position as chairman of the new committee to promote total abolition. In February of 1864, just before delivering his “Prayer” speech, he introduced a constitutional amendment to end slavery, asking that it be referred to his Select Committee on Slavery and Freedmen, although Senate practice dictated otherwise. Judiciary Committee chairman Lyman Trumbull objected, insisting that his committee was the proper one to consider such proposals. The Senate sided with Trumbull.

When the Judiciary Committee reported its version of an abolition amendment to the full Senate, Sumner thought it was not strong enough. He had insisted that any amendment must include a provision that all persons were “equal before the law,” but few senators were ready to take such a bold step. Making all persons “equal before the law,” argued one senator, might lead to dangerous consequences, such as providing voting rights to women. Instead, the committee approved more modest language that echoed the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.” Although the statement was less than Sumner had hoped for, he joined his colleagues in voting for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in April of 1864.

In the years following the Civil War, Sumner recognized that abolition was only the beginning of the battle for civil rights. He used what power he could muster to protect the gains that African Americans had made in the South and urged his colleagues to approve mobilization of federal resources to do so. He emerged as a leading opponent of President Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction policies, which Sumner and other Radical Republicans believed were designed to reinstate white supremacy in the former Confederate states. He supported impeachment and removal of the president in 1868, though the Senate came up one vote short of conviction.

Sumner’s steadfast defense of his principles often led him to oppose compromise measures. He believed that the government owed former slaves a guarantee of their suffrage rights, along with support for education and land ownership. Sumner initially opposed the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which declared that African Americans were citizens entitled to equal protection of the laws, because it did not contain a clear guarantee of voting rights. Ultimately, he cast his vote in favor of the amendment. Never shy about chastising his fellow Republicans for not going far enough, Sumner took every opportunity to place the question of equal rights before the Senate. Such radical views stirred action, but they also made enemies. “If I could cut the throats of about half a dozen senators,” confessed William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, “Sumner would be the first victim.”4

In 1870 Sumner introduced what he considered to be his most important piece of legislation, a civil rights bill to guarantee to all citizens, regardless of color, “equal and impartial enjoyment of any accommodation, advantage, facility, or privilege.” Sumner had characterized segregation and other anti-black laws in the South as “nothing but the tail of slavery,” and he predicted his civil rights bill would be the greatest achievement of Reconstruction. “Very few measures of equal importance have ever been presented,” he proclaimed.5

Unfortunately, Sumner’s idealistic and uncompromising stance had alienated him from many of his Senate colleagues, and the bill failed. In 1871 he even lost his influential position atop the Foreign Relations Committee when he entered into a fierce public battle with President Ulysses S. Grant over plans to annex Santo Domingo. The party caucus sided with Grant and removed Sumner as chairman. Despite becoming increasingly isolated within his party, Sumner persisted and continued to introduce the civil rights bill. After suffering a heart attack in 1874, Sumner’s final thoughts remained with his bill. The dying Sumner pleaded with Frederick Douglass and others at his bedside: “Don’t let the bill fail. You must take care of [my] civil rights bill.”6 Sumner did not live to see the fate of his bill.

When Sumner died on March 11, 1874, his supporters mourned him as a national leader. Thousands passed by his casket in the Capitol Rotunda, where it was placed on the same catafalque that had held President Lincoln’s casket a decade before. Thousands more lined the train route by which the senator’s body was transported north and were present upon its arrival in Massachusetts. As he lay in state in the Massachusetts State House, soldiers of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, composed of African American soldiers who had fought in the Civil War, stood guard. The Springfield Republican lamented: “The noblest head in America has fallen, and the most accomplished and illustrious of our statesmen is no more.”7

As a final tribute to their often-difficult colleague, senators passed an amended version of Sumner’s bill, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, but again Sumner proved to be ahead of his time. The Supreme Court struck down the law as unconstitutional in 1883. It would take another 80 years for Sumner’s ideas to gain full legislative endorsement—with the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

If you seek the source of Sumner’s fame, look to the caning. To truly understand the importance of Sumner’s enduring legacy as statesman and legislator, however, you need to explore the career that came after the caning.

Notes

1. Quoted in David Donald, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man (New York: Knopf, 1970), 29.

2. Donald, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man, 148.

3. Congressional Globe (38th Cong., 1st Sess.), February 9, 1864, p. 536.

4. William Pitt Fessenden to Elizabeth Fessenden Warriner, June 1, 1862, quoted in Eric L. McKitrick, Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 272.

5. Congressional Globe (38th Congress, 1st Session), May 13, 1864, p. 2246; Sumner to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, February 25, 1872, in Edward Lillie Pierce, Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner, 1860-1874 (Boston, 1894), 502.

6. Pierce, Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner, 1860-1874, 598.

7. Quoted in Donald, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man, 8.

|

| 202002 25Hiram Revels: First African American Senator

February 25, 2020

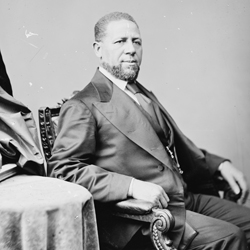

One hundred and fifty years ago, on February 25, 1870, visitors in the packed Senate galleries burst into applause as Senator-elect Hiram Revels, a Republican from Mississippi, entered the Chamber to take his oath of office. Those present knew that they were witnessing an event of great historical significance. Revels was about to become the first African American to serve in the United States Congress.

Welcome to Senate Stories, our new Senate history blog. In recognition of Black History Month, our first blog post celebrates the sesquicentennial of the swearing in of Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African American senator.

One hundred and fifty years ago, on February 25, 1870, visitors in the packed Senate galleries burst into applause as Senator-elect Hiram Revels, a Republican from Mississippi, entered the Chamber to take his oath of office. Those present knew that they were witnessing an event of great historical significance. Revels was about to become the first African American to serve in the United States Congress. Just 22 days earlier, on February 3, the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, prohibiting states from disenfranchising voters “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Revels was indeed “the Fifteenth Amendment in flesh and blood,” as his contemporary, the civil rights activist Wendell Phillips, dubbed him.

Hiram Revels was born a free man in Fayetteville, North Carolina, on September 27, 1827, the son of a Baptist preacher. As a youth, he took lessons at a private school run by an African American woman and eventually traveled north to further his education. He attended seminaries in Indiana and Ohio, becoming a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1845, and eventually studied theology at Knox College in Illinois. During the turbulent decade of the 1850s, Revels preached to free and enslaved men and women in various states while surreptitiously assisting fugitive slaves.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Revels was serving as a pastor in Baltimore. Before long, he was forming regiments of African American soldiers in Maryland, serving as a Union army chaplain in Mississippi, and establishing schools for freed slaves in Missouri. He settled in Natchez, Mississippi, at war’s end, where he served as presiding elder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1868 he gained his first elected position, as alderman for the town of Natchez. The next year he won election to the state senate, as one of 35 African Americans elected to the Mississippi state legislature that year.

In 1870, as Mississippi sought readmission to representation in the U.S. Congress, the Republican Party firmly controlled both houses of Congress and also dominated the southern state legislatures. That, along with the pending ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, set the stage for the election of Congress’s first African American members. One of the first orders of business for the new Mississippi state legislature when it convened on January 11, 1870, was to fill the vacancies in the United States Senate, which had remained empty since the 1861 withdrawal of Albert Brown and future Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Representing around one-quarter of the state legislative body, the black legislators insisted that one of the vacancies be filled by a black member of the Republican Party. “An opportunity of electing a Republican to the United States Senate, to fill an unexpired term occurred,” Revels later recalled, “and the colored members after consulting together on the subject, agreed to give their influence and votes for one of their own race for that position, as it would in their judgement be a weakening blow against color line prejudice.” Since Revels had impressed his colleagues with an impassioned prayer at the opening of the session, legislators agreed that the shorter of the two terms, set to expire in March 1871, would go to him.

Mississippi gained readmission on February 23, 1870, and Senator Henry Wilson, one of the Senate’s strongest civil rights advocates, promptly presented Revels’s credentials to the Senate. Immediately, three senators issued a challenge. They charged that Revels had not been a U.S. citizen for the constitutionally required nine years. Citing the 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision, they argued that Revels did not gain citizenship until at least 1866, with passage of that year’s civil rights act, and perhaps not until the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868. By this logic, Revels could claim that he had been a U.S. citizen for, at most, four years.

Revels and his supporters dismissed the challenge. The Fourteenth Amendment had repealed the Dred Scott decision, they insisted, and they pointed out that long before 1866 Revels had voted in the state of Ohio. Certainly that qualified him as a citizen. “The time has passed for argument. Nothing more need be said …. For a long time it has been clear that colored persons must be senators,” Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner declared, bringing the debate to an end with a stirring speech. “All men are created equal, says the great Declaration, and now a great act attests to this verity. Today we make the Declaration a reality.” By an overwhelming margin, the Senate voted 48 to 8 to seat Revels. Escorted to the well by Senator Wilson, Revels took the oath of office on February 25, 1870.

Three weeks later, the Senate galleries were again filled to capacity as Revels rose to deliver his maiden speech. Seeing himself as a representative of African American interests throughout the nation, Revels spoke against an amendment to the Georgia readmission bill that could be used to prevent blacks from holding state office. “Perhaps it were wiser for me, so inexperienced in the details of senatorial duties, to have remained a passive listener in the progress of this debate,” he began, acknowledging the Senate tradition of waiting a year or more to deliver a major address, “but when I remember that my term is short, and that the issues with which this bill is fraught are momentous in their present and future influence upon the well-being of my race, I would seem indifferent to the importance of the hour and recreant to the high trust imposed upon me if I hesitated to lend my voice on behalf of the loyal people of the South.”

Revels made good use of his time in office, championing education for black Americans, speaking out against racial segregation, and fighting efforts to undermine the civil and political rights of African Americans. When his brief term ended on March 3, 1871, he returned to Mississippi, where he later became president of Alcorn College.

During the Reconstruction Era, a total of 17 African Americans served in the United States Congress, 15 in the House of Representatives and two in the Senate. In 1874 the Mississippi legislature elected Blanche K. Bruce to a full Senate term. Bruce, who had escaped slavery at the outbreak of the Civil War, became the first African American to preside over the Senate in 1879. Another eight decades passed before Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts followed in Revels and Bruce’s historic footsteps to take office in 1967.

The significance of the courageous and pioneering service of Revels, Bruce, and the other African American congressmen of the Reconstruction Era cannot be overstated. Although the struggle to fully achieve equality would continue for years to come, their remarkable accomplishments opened doors for others to follow.

|