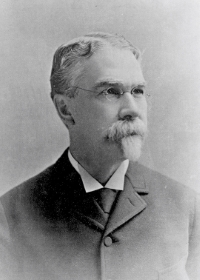

Leading up to the centennial commemoration of Washington, D.C., in 1900, architects, engineers, and other interested parties had begun to develop several competing plans to redesign and improve the capital city, particularly the public space now known as the National Mall. Decades of haphazard development had produced a city that hardly resembled the original plan designed by Pierre Charles L'Enfant in 1791. Among those dedicated to improving the design at the dawn of the 20th century was Michigan senator James McMillan. As chairman of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, McMillan used his position to promote a far-sighted plan to beautify the nation’s capital.

A transportation industry magnate, philanthropist, and leader of the Republican Party machine in Michigan, McMillan came to the Senate in 1889 and quickly established himself as a hard-working and influential senator. He developed strong relationships with his Senate colleagues, founding the “School of Philosophy Club,” a gathering of powerful Republican senators who met at his home to fine tune their legislative agenda. Named chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia in 1891, McMillan immersed himself in work to improve the city’s infrastructure, including the streetcar, railway, and water systems. A longtime patron of the arts and promoter of cultural civic improvements, McMillan also became heavily invested in efforts to develop and beautify the Mall, the city’s central feature, which had greatly expanded with recent efforts to fill in and reclaim the tidal flats of the Potomac River near the Washington Monument.1

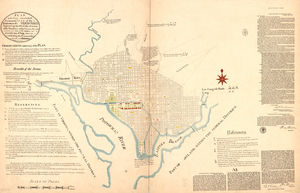

Washington, D.C., was unique in that a plan for the nation’s capital city had been designed at its inception. The 1790 Residence Act established a federal district along the Potomac River to include the city as the permanent seat of government. It authorized President George Washington to appoint three commissioners to survey and define the boundaries of the district and to provide for public buildings to accommodate the government by 1800. In 1791, under the auspices of this law, Washington charged L'Enfant, a military engineer who had served on Washington's staff during the Revolutionary War, with creating a plan for the city. L'Enfant proposed a grid system of residential streets with broad diagonal avenues radiating from the principal governmental buildings—the “President’s House” and “Congress House.” The centerpiece of L'Enfant's plan was a Mall, where he envisioned a dedicated public space for learning and recreation—a “place of general resort,” a tree-lined “grand avenue,” surrounded by “play houses, room[s] of assembly, academies and all sort of places as may be attractive to the learned and afford diversion to the idle.” L’Enfant “conceived the capital as the seat of a ‘vast empire,’” one scholar wrote, and the Mall was “the physical and symbolic heart” of his plan.2

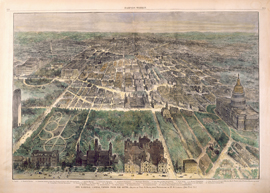

During the century that followed, much of L’Enfant’s design for the Mall never materialized. The young republic was not equipped financially or organizationally to fulfill such a plan. L'Enfant's grand and cohesive vision was gradually lost to decentralized and private land development. “Over time, as the view from the west front of the Capitol affirmed,” noted one historian, “the Mall had devolved into a hodgepodge of misplaced buildings, odd structures, and meandering garden paths, all constructed without regard for [L’Enfant’s] intentions.” As another historian wrote, “By 1900 … the Mall had become a chain of individual public parks, each associated with a different Victorian building, most of them built of red brick.” Among the developments that violated L’Enfant’s original design was the terminal of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad at Sixth Street west of the Capitol. The terminal was constructed in 1870 and its tracks cut directly across the Mall, proving to be both an eyesore and a safety concern.3

As the 19th century drew to a close, several groups consisting of local and state authorities as well as members of Congress emerged to discuss plans for a centennial celebration of the capital city. In a February 1900 meeting of the various groups, participants created a special committee of five to review suggestions and make final recommendations and chose Senator McMillan to serve as chairman. McMillan and the committee subsequently proposed a celebration in December 1900 that would include commemorative exercises in both houses of Congress along with a parade and a reception. The committee also recommended a plan to revive L’Enfant’s original vision by converting the entire Mall into a grand boulevard named Centennial Avenue. “Upon looking at the maps which the committee had before it,” McMillan noted, “it was seen that the original plan of Washington, as prepared by Major L’Enfant, provided for just such an avenue, public buildings to be erected on either side of the same.”4

Other organizations and agencies invested in the development of the District criticized the committee’s plan for not being fully developed. Throughout the centennial year, architects and planners from various organizations continued to produce competing designs. The debate culminated in the annual convention of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) held in Washington in December of 1900 to coincide with the centennial celebration. Architects attending the convention presented several additional plans, hoping to draw attention to the subject of beautifying Washington. “It is intended by these papers to call the attention of Congress forcibly to the need of some harmonious scheme to be followed in the future development of Washington,” AIA secretary and noted Capitol historian Glenn Brown wrote. “We propose to have the reading and discussion open to the public and invite all Congressmen and officials to attend."5

Within days, McMillan and other members of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia met with AIA members to craft a joint congressional resolution authorizing the president to appoint a commission “to study and report on the location and grouping of public buildings and the development of the park system in the District of Columbia.” When the House of Representatives showed little interest in the joint resolution, McMillan instead secured passage of a Senate resolution in March 1901. This resolution authorized the Committee on the District of Columbia to form a commission of experts “to consider the subject and report to the Senate plans for the development and improvement of the entire park system of the District of Columbia.” Although McMillan’s resolution focused generally on the city’s park system, his true purpose soon became apparent. “It was obvious from his actions in the following weeks,” noted one historian, “that what he had in mind was nothing less than a comprehensive development plan for all of central Washington in addition to certain studies of Rock Creek and Potomac Parks.”6

The District of Columbia Committee consulted the AIA to determine who should be on the new Senate Park Commission, which became known as the McMillan Commission due to the senator’s prominent role in its creation. The organization recommended architect Daniel Burnham, who had successfully transformed Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, as well as landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who had presented at the AIA convention and urged a return to the “greatness” of L’Enfant’s original plan. McMillan’s longtime aide Charles Moore played an influential role as the commission’s secretary and helped to draft much of the final report. Members of the commission agreed to focus on restoring L’Enfant’s vision for the Mall, and, as expressed by Burnham, “make the very finest plans their minds could conceive.” They set to work surveying the existing landscape of Washington and studying the plethora of proposals for its beautification. In the summer they embarked on a lengthy tour of European cities, “intended as a systematic exploration of the sources of inspiration that had guided L'Enfant’s original plan and an examination of current European treatment of civic architecture and its relationship to open spaces.”7

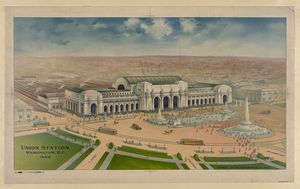

One of the principal challenges facing the commission was the domineering presence of the railway terminal. As a businessman with lifelong ties to the railroad industry, McMillan assumed a perpetual presence of a railway terminal on the Mall, but members of the commission disagreed. “Mr. Burnham…informed me…that little could be done toward beautifying the Mall as long as the railroad tracks were allowed to cross it," McMillan told a reporter. "The problem then was to get rid of the station." This presented quite a challenge, but the McMillan Commission ultimately succeeded in securing an agreement with the Pennsylvania Railway Company and its subsidiary, the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad, to relocate the terminal. Provided “the Government would meet the company in a spirit which would enable him to justify the move to the stockholders,” the railway company president agreed to consolidate its rail lines to the proposed Union Station terminal north of the Capitol. The station’s design became a core component of the commission’s plan. "This great station forms the grand gateway to the capital, through which every one who comes to or goes from Washington must pass,” the commissioners wrote in their report, calling it “the vestibule" of the capital. “The three great architectural features of a capital city being the halls of legislation, the executive buildings, and the vestibule," the commissioners added, “the style of this building should be equally as dignified as that of the public buildings themselves." The hallmark contribution of the elegantly designed Union Station would become one of the enduring legacies of the Senate Park Commission.8

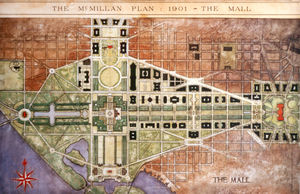

The commission unveiled its plan to an excited crowd at the Corcoran Gallery in January 1902, complete with two scale models—one showing the city’s central core at present, and one displaying the commission’s ambitious plan. The exhibit also featured maps and artists’ sketches of proposed improvements to the city. In its report, the commission emphasized its fundamental allegiance to L’Enfant’s design. "During the century that has elapsed since the foundation of the city the great space known as the Mall…has been diverted from its original purpose and cut into fragments, each portion receiving a separate and individual informal treatment, thus invading what was a single composition," the commissioners wrote. "The original plan…has met universal approval. The departures from that plan are to be regretted and, wherever possible, remedied."9

The scaled models showed the National Mall as an extensive park that stretched from the Capitol to the Potomac River. Stately museums faced each other across a wide lawn. A new monument to Abraham Lincoln anchored the western end, connected by a long reflecting pool to the Washington monument. A decorative memorial bridge spanned the river to Arlington, Virginia. It was a bold and ambitious plan to create a common, national space. Beyond the Mall, the commission developed expansive plans that included a neighborhood park system, scenic parkways, reclamation of the tidal flats in Anacostia, and several public buildings. As their report indicated, the commissioners understood the ambitious nature of the plan and knew that what they conceived would be a guide for the city's development for generations to come. "The task is indeed a stupendous one; it is much greater than any one generation can hope to accomplish," they wrote, noting that their objective was "to prepare … such a plan as shall enable future development to proceed along the lines originally planned—namely, the treatment of the city as a work of civic art."10

James McMillan’s sudden death in August 1902 prevented him from seeing the fruits of his labor. The legacy of the McMillan Commission endured, however, and while its proposed plan has not always been strictly followed, many of its recommendations have become a reality. The plan has served as a guide for the development of Washington, as well as providing a model for city planners across the country. In 1910 Congress established a permanent federal commission, the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, "to ensure that the McMillan Plan for the National Mall was completed with the highest degree of civic art." In 1926 Congress established the National Capital Planning Commission, still in existence, "to ensure the continuation of good planning for the city in the tradition of L'Enfant and McMillan." The McMillan Commission’s report and models “were at once a blueprint for the future of the capital and an early twentieth-century primer for enlightened urban planning,” concluded one historian. McMillan's efforts ultimately succeeded in producing a design that would remain true to L’Enfant’s 1791 vision, while simultaneously reshaping the heart of the city into a modern showplace.11

Notes

1. Geoffrey G. Drutchas, “Gray Eminence in a Gilded Age: The Forgotten Career of Senator James McMillan of Michigan,” Michigan Historical Review 28, no. 2 (Fall 2002): 94; Geoffrey G. Drutchas, "The Man with a Capital Design," Michigan History 86 (March/April 2002): 33–34; Pamela Scott and Antoinette J. Lee, Buildings of the District of Columbia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 76.

2. John W. Reps, Monumental Washington: The Planning and Development of the Capital Center (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967), 17; Jon A. Peterson, "The Senate Park Commission Plan for Washington, D.C.: A New Vision for the Capital and the Nation," in Designing the Nation's Capital: The 1901 Plan for Washington, D.C., ed. Sue Kohler and Pamela Scott (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2006), 2.