| 202409 05The Senate and the 1994-95 Baseball Strike

September 05, 2024

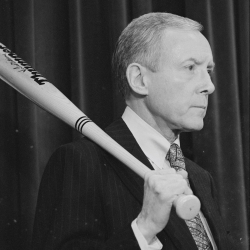

On August 12, 1994, members of the Major League Baseball Players Association began a strike—the threat of which had been hanging over the sport all summer—and nobody knew just how long it would last. Negotiations had stalled on a collective bargaining agreement between owners and players. Given the heated rhetoric on both sides of the dispute, it seemed highly unlikely that a resolution would develop anytime soon. As it turned out, the 1994 baseball strike led to a cancelled World Series, millions of heartbroken fans, and a series of bipartisan efforts by United States senators to save America’s pastime.

At approximately 11:28 p.m. on August 11, 1994, Ricky Jordan strode to home plate, bat in hand, hoping to win the game for the Philadelphia Phillies. It was the bottom of the 15th inning, two outs, and the score knotted 1-1 against the rival New York Mets. Mauro Gozzo toed the rubber; Jordan readied in his stance. A second later, the crack of Jordan’s bat sent a ground ball into left field and the Phillies to a 2-1 victory, the type of ending that seemed to only happen in the movies.1

The Phillies crowd, 37,605 strong, should have been elated, but the response was oddly tempered for good reason. They—and every other baseball fan for that matter—knew there would be no baseball the next day. Baseball players were set to strike starting August 12, a reality that had been hanging over the sport all summer, and nobody knew just how long it would last. An accurate assessment of public sentiment came just after the Phillies game from star player Lenny Dykstra: “Dude, this really sucks.”2

The 1994 Major League Baseball (MLB) season had begun under ominous circumstances. The league’s collective bargaining agreement (CBA) signed with the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) had expired on December 31, 1993. Games continued in the spring of 1994 even while negotiations stalled. Club owners delivered their first proposal to the MLBPA on June 14, which the players summarily rejected. A month later, with the two sides no closer to an arrangement, the MLBPA announced that if an agreement was not reached by August 12, players would strike. August 12 arrived and, with no deal in place, all games were canceled. Given the heated rhetoric on both sides, it seemed highly unlikely that an agreement would develop anytime soon. As it turned out, the 1994 baseball strike led to a cancelled World Series, millions of heartbroken fans, and a series of bipartisan efforts by United States senators to save America’s pastime.3

Congressional Action

Senator Howard Metzenbaum, a Democrat from Ohio who chaired the Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies, and Business Rights, watched intently as the 1994 baseball season collapsed. His subcommittee had been exploring problems in professional baseball for several years, specifically the sport’s antitrust exemption, a legal arrangement stemming from a 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case that determined that the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which prohibited monopolistic business practices, did not apply to Major League Baseball. The Court’s ruling had broad implications, but it primarily meant that professional baseball players and umpires were not afforded the same legal protections as those in other professional sports. When it came to labor disputes, a strike was the only available negotiation tactic. The Supreme Court heard multiple cases between 1922 and 1994 challenging baseball’s antitrust exemption, yet the majority consistently upheld the original ruling while noting that Congress could pass legislation at any time to repeal the exemption.4

Since the 1950s, Senate committees had periodically held hearings on the economics of professional sports, but the baseball antitrust exemption had largely escaped close scrutiny. That ended in December 1992 when Metzenbaum’s subcommittee held a hearing regarding “the validity of MLB’s exemption from the antitrust laws.” In his opening statement, Chairman Metzenbaum asserted that Major League Baseball had become “a legally sanctioned, unregulated cartel.” During the hearing, other committee members expressed their belief that baseball club owners did not look out for the interests of fans, especially since the league had not hired a new commissioner after ousting Fay Vincent from that role earlier in 1992. Without a commissioner to manage the league, some senators argued that professional baseball essentially had no oversight in light of the antitrust exemption and that Congress had a duty to fill that role.5

Both Metzenbaum and the subcommittee’s ranking member, Republican Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, hammered baseball team owners on the issue. “The implications for fans are ominous,” Senator Metzenbaum observed. “Every time there has been a labor negotiation in baseball, there has been either a strike or a lockout.” Senator Thurmond argued professional baseball’s current structure was so outdated that, were it proposed in 1992, it would be “laughed out of the Hart [Senate] Office Building.” Other senators hedged on what they considered the radical step of repealing the antitrust exemption. Republican senator Orrin Hatch of Utah warned that doing so could have unknown consequences. Democratic senator Dianne Feinstein of California, in a joint statement with Senator-elect Barbara Boxer of California, argued the exemption was needed to protect cities from arbitrary franchise relocation because “baseball is not a product like a box of Tide that can be sold in a supermarket…. Baseball is part of the fabric and unity of the American city.” Feinstein furthered that baseball was not a business but an American tradition and should maintain the antitrust exemption.6

More than a year later, on March 4, 1994, with spring training underway and negotiations for a collective bargaining agreement stalled, Senator Metzenbaum introduced the Professional Baseball Antitrust Reform Act to revoke baseball’s antitrust immunity. Six Democrats and three Republicans co-sponsored the bill. The subcommittee held a hearing on the legislation on March 21, 1994, five months before the strike would begin. In an effort to maximize public attention, Metzenbaum held the hearing at the Bayfront Center arena in St. Petersburg, Florida, directly across the street from the historic Al Lang Stadium, where spring training games took place. Metzenbaum did not mince words, calling the league an “overprivileged owners’ cartel” while calling for Congress to “reclaim our national pastime for the fans before the barons of baseball become too cozy, too comfortable, and too cocky.” Despite his efforts, the full Judiciary Committee voted down Metzenbaum’s bill 10 to 7 on June 23, 1994, effectively ending Senate intervention for the time being. The bill’s opponents felt uneasy about interfering in ongoing labor negotiations as well as the unintended consequences that the legislation could have on other labor unions going forward.7

Throughout the 1994 summer, legislators stayed mostly quiet on the pending baseball strike, but behind the scenes, many crafted legislation that would, if necessary, return players and fans to ballparks. Senators may have been reluctant to confront the antitrust exemption, but a growing consensus was emerging that action should be taken to address a strike. Once the August 12 strike ultimatum arrived, a bipartisan group of senators, led by Metzenbaum, Thurmond, Hatch, and Democrat Patrick Leahy of Vermont, initiated what would become Congress’s most direct intervention between sports and labor.8

The Strike Begins

As the players’ strike began on August 12, senators continued to grapple with the question of what role, if any, Congress should play in a private labor dispute. “The real message should be a wake-up call to baseball,” Senator Hatch commented. “If you do not want Congress to be involved, then settle this dispute yourself.” Democratic senator Dennis DeConcini of Arizona pointed out that “the Government is already involved [in baseball] and has, in effect, created a baseball monopoly.” “In other instances where we create a monopoly,” he observed, “such as utilities, no one questions the Government’s authority to regulate.” Most senators who favored action wanted to target the antitrust exemption. MLBPA leader Donald Fehr had, in fact, informed Senator Metzenbaum that players would end the strike—thus saving the 1994 season—if Congress ended the antitrust exemption.9

Senators who opposed congressional action, such as Republican David Durenberger of Minnesota and Democrat Harris Wofford of Pennsylvania, argued that it would be bad precedent for Congress to intervene in strikes and that revoking the antitrust exemption would damage the economic fortunes of minor league teams and MLB teams in smaller markets. Pennsylvania Republican Arlen Specter suggested that Congress could offer no solution beyond encouraging arbitration.10

Meanwhile, a nightmare befell baseball fans when on September 14, 1994, Milwaukee Brewers owner and now acting commissioner Bud Selig announced the World Series was cancelled for the first time in 90 years. Two weeks later, Senators Metzenbaum and Hatch, who now favored antitrust legislation in part due to the strike, revived antitrust legislation for an 11th-hour floor vote, but it was blocked by Nebraska senator J. James Exon on grounds that it would “set a bad precedent” and that “this is not the proper time or action for the Senate to become involved in the matter of professional baseball.” The amendment was then withdrawn, one of Senator Metzenbaum’s final Senate acts before his retirement. Throughout the winter of 1994–95, all negotiations failed, including proposals put forth by both the White House and the House of Representatives.11

The 104th Congress

When the 104th Congress convened on January 4, 1995, senators watched while President William J. Clinton summoned MLB and MLBPA leaders to the White House. If a settlement was not reached by February 7, Clinton announced, he would issue recommendations to Congress for legislative action. As expected, the president’s deadline passed with no resolution. Senate Majority Leader Robert J. “Bob” Dole of Kansas explained he was “very, very reluctant” to intervene with legislation, and the Wall Street Journal reported that Congress would offer “nonlegislative support” as it further deliberated the antitrust exemption.12

When the owners indicated they would begin the 1995 season by hiring non-union, replacement players—a tactic used by the National Football League in 1987—lawmakers renewed their efforts to force a deal. Senator Metzenbaum’s retirement meant the Senate had lost a powerful voice in the baseball fight, but several others stepped up to the plate. In early February 1995, Democratic senator Edward M. “Ted” Kennedy of Massachusetts introduced legislation drafted by the White House that would establish a dispute resolution panel to impose a binding agreement on the players and owners. Kennedy implored his colleagues, “The question is who speaks for Red Sox and millions of other fans across America. At this stage in the deadlock, if Congress does not speak for them, it may well be that no one will.” Meanwhile, Judiciary Committee chairman Hatch worked with Democratic senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York on a new antitrust bill, while Senators Thurmond and Leahy simultaneously collaborated on their own antitrust legislation.13

Two bills that would repeal baseball’s antitrust exemption emerged from this work—the Hatch-Moynihan and Thurmond-Leahy bills—and both were introduced on February 14, 1995. Donald Fehr had privately informed Hatch days earlier that the MLBPA would end the strike were the Hatch-Moynihan bill to pass. Senator Thurmond’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Business Rights, and Competition held hearings on both bills one day after their introduction, with members still debating whether to intervene. Leahy argued that “there is a public interest in the resumption of true, major league baseball”—a dig at replacement players—and advocated for Congress to finally establish an antitrust regulatory framework. Republican senator Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas, who opposed intervention, argued that “absent a national emergency,” legislation would set “a very dangerous precedent.” Senator Howell Heflin of Alabama, a Democrat, agreed, noting the unknown effect such legislation may have upon “the price of baseball overall—players’ salaries, owners’ money, the division, whatever.” Senator Thurmond argued that baseball’s antitrust exemption should be revoked regardless of the strike, the same position he held in 1992.14

Acting commissioner Bud Selig testified at the hearings alongside Donald Fehr and star players Eddie Murray and David Cone. Murray vented his frustrations with the antitrust exemption: “Should fire codes not apply to stadiums because baseball is unique? Should health codes not apply to hot dogs sold in baseball stadiums? Should civil rights not apply to baseball? It sounds stupid to me, but why does the antitrust exemption make any difference?” Selig warned that Major League Baseball faced a dire financial situation, which would only be exacerbated by congressional intervention. Selig further claimed that the antitrust exemption was “irrelevant in the labor area” and only affected franchise relocation and minor league baseball. In response to Selig’s position, Senator Moynihan remarked that if “the owners believe [the antitrust exemption] is irrelevant to the strike…then they shouldn’t mind if we repeal it.”15

After the hearings ended, senators put neither bill to a vote, hoping that a CBA settlement would soon be reached. However, negotiations continued to falter into late March. With the MLB season’s opening day with replacement players just days away, Senators Hatch, Thurmond, and Leahy introduced a unified compromise bill with the co-sponsorship of Senators Moynihan and Bob Graham of Florida. This action came just one day after the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) made a player-friendly ruling on the dispute. The MLBPA again made it publicly known that players would return to the field if either the bill passed or a federal court issued the injunction sought by the NLRB.16

As Congress deliberated, a federal court intervened. On March 31, 1995, just days before the 1995 season would have normally begun, U.S. District Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor issued the injunction sought by the NLRB, effectively ending the strike. While not a long-term solution, the injunction broke the gridlock and returned players and fans to America’s professional baseball fields.17

The Curt Flood Act

The drama surrounding the Senate’s legislative efforts dissipated once baseball players returned to the diamond in April 1995, but the group of senators who wanted to end baseball’s antitrust exemption continued to press the issue. Senators Hatch, Leahy, Thurmond, and Moynihan reintroduced similar legislation in the 105th Congress, though this time it bore the name the Curt Flood Act of 1997.18

Naming the bill after Flood was timely and appropriate, as Senator Leahy noted, given Flood’s sacrifice and legacy in challenging baseball’s economic system. Curt Flood, an all-star outfielder for the St. Louis Cardinals, had filed a historic lawsuit against the MLB in 1969 over perceived contractual mistreatment, thereby challenging the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1922 ruling that established baseball’s antitrust exemption. On January 3, 1970, famed broadcaster Howard Cosell questioned Flood on ABC’s Wide World of Sports: “What’s wrong with a guy making $90,000 being traded…those aren’t exactly slave wages.” Flood, an African American, quipped, “A well-paid slave is nonetheless a slave.” Flood willingly chose this unprecedented action in an effort to better the economic conditions of not just himself, but all professional ballplayers. However, two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld baseball’s antitrust exemption in Flood v. Kuhn (1972) despite admitting the apparent “inconsistency or illogic" within the original 1922 decision. After filing his lawsuit, Flood played in just 13 games; his professional career was over. Blackballed from professional baseball, Flood retired to private life where he worked as a sportscaster and business owner while also painting portraiture. He died on January 20, 1997, at the age of 59. Upon Flood’s death, senators honored his effort on behalf of baseball players by naming the legislation after him.19

Importantly, the Curt Flood Act included significant legislative compromises, which helped it overcome hurdles faced by earlier legislative attempts. It explicitly excluded minor league baseball from its purview, thus alleviating concerns from minor league owners and some senators who had opposed earlier bills. After another round of hearings and input from the MLBPA and club owners, the Curt Flood Act passed the Senate by unanimous consent on July 30, 1998, and the House by voice vote on October 7. President Clinton signed it into law less than three weeks later. Though affecting only major league players, it marked the first time that Congress established a legislative solution to the Supreme Court’s 1922 antitrust ruling. As Senator Leahy noted in his floor remarks on the bill, “The certainty provided by this bill will level the playing field, making labor disruptions less likely in the future. The real beneficiaries will be the fans. They deserve it.”20

The 1994 baseball strike was the most impactful sports labor stoppage in U.S. history when measured by games cancelled, lost revenue, and congressional response. The Curt Flood Act, while years in the making, demonstrated bipartisan efforts by senators to correct what was, in their view, an unjust reality for major league baseball players. The bill’s impact is still being measured, but it did empower, in theory, individual MLBPA members to file suit like Curt Flood did in 1969. This bill also brought Curt Flood, a name largely forgotten to all but the most ardent of baseball fans, back into public discourse. Minutes before the Senate passed the Curt Flood Act, Senator Leahy concluded, “When others refused, [Curt Flood] stood up and said no to a system that he thought un-American.…I am sad that he did not live long enough to see this day.”21

Notes

1. “Philadelphia Phillies 2, New York Mets 1,” Retrosheet, https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1994/B08110PHI1994.htm.

2. Tim Kurkjian, “’Oh my God, How Can We Do This?’: An Oral History of the 1994 MLB Strike,” ESPN, Aug. 12, 2019; Kevin Kaduk, “August 11, 1994: Scenes from a Lost MLB Season,” Yahoo Sports, Aug. 9, 2019, accessed August 28, 2024, https://sports.yahoo.com/august-11-1994-scenes-from-a-lost-season-042806980.html.

3. Paul Staudohar, “The Baseball Strike of 1994-5,” Monthly Labor Review 120, no. 3 (March 1997): 24–25; Nick Cafarado, "Q&A Everything You Wanted to Know about Baseball's Impending Strike but were Afraid to Ask," Boston Globe, August 9, 1994; Mark Maske, “At All-Star Break, No Relief for Baseball,” Washington Post, July 11, 1995; Murray Chass, “On Baseball,” New York Times, August 2, 1994; Ross Newhan, “The Players’ Donald Fehr and the Owners’ Richard Ravitch Have Mastered the South Bite,” Los Angeles Times, August 14, 1994; Tom Fitzpatrick, “The Baseball Strike: As Boring as it is Stupid,” Phoenix New Times, August 18, 1994; Thom Loverro, "The Baseball Strike: Close to the Action," Columbia Journalism Review 33, no. 6 (March 1995): 12.

4. Federal Baseball Club v. National League, 259 U.S. 200, 208-09 (1922); “Baseball and the Supreme Court,” Society of American Baseball Research Century Committee, accessed August 28, 2024, https://sabr.org/supreme-court/antitrust; Samuel Alito, “The Origin of the Baseball Antitrust Exemption,” Journal of Supreme Court History 34, no. 2 (July 2009): 183–95; Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc., 346 U.S. 356, 356–57 (1953); “Part 2: Baseball and the Antitrust Laws: The Unique Antitrust Status of Baseball,” in Neil B. Cohen, Paul Finkelman, and Spencer Weber Waller, eds., Baseball and the American Legal Mind (New York: Garland Pub., 1995), 75–160. For more on the antitrust exemption within the broader sporting landscape, see David George Surdam, The Big Leagues Go to Washington (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015).

5. Surdam, Big Leagues, 42–51; Examples of hearings include: Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subjecting Professional Baseball to Antitrust Laws: Hearings on S.J. Res. 133 to Make the Antitrust Laws Applicable to Professional Baseball Clubs Affiliated with the Alcoholic Beverage Industry, 83rd Cong., 2nd sess., March 18, April 8, May 25, 1954; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Professional Sports Antitrust Immunity: Hearings on S. 2784 and S. 2821, 97th Cong., 2nd sess., August 16, September 16, 20, 29, 1982; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Professional Sports Antitrust Immunity: Hearings on S. 172, S. 259, and S. 298, S.Hrg. 99-496, 99th Cong., 1st sess., February 6, March 6, June 12, 1985; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies and Business Rights on the Movement of Sports Programming onto Cable Television, S. Hrg. 101-1209, 101st Cong., 1st sess., November 14, 1989. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Baseball’s Antitrust Immunity: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies, and Business Rights on the Validity of Major League Baseball’s Exemption from the Antitrust Laws, S. Hrg. 102-1094, 102nd Cong. 2nd sess., Dec. 10, 1992.

6. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, S. Hrg. 102-1094, 2, 56, 330; L. Elaine Halchin, Justin Murray, Jon O. Shimabukuro, and Kathleen Ann Ruane, “Congressional Responses to Selected Work Stoppages in Professional Sports,” Congressional Research Service (CRS) R41060, updated January 15, 2013, 1.

7. Professional Baseball Antitrust Reform Act of 1993, S.500, 103rd Congress, 1st sess., 1993; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Professional Baseball Teams and the Antitrust Laws: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies, and Business Rights on S. 500, S.Hrg. 103-1054, Mar. 21, 1994, 1-4; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Legislative and Executive Calendar, Final Edition, S. Prt. 103-113, 103rd Congress, 18; Dave Kaplan, “Bill to Avert Baseball Strike Thrown Out by Senate Panel,” Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report, Vol. 52, No. 5, June 25, 1994, 1700; Tom Korologos to Senator Moynihan, 21 Sep. 1994, Folder 12, Box 574, Daniel P. Moynihan papers, 1765-2003, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

8. Halchin, et al, CRS Report, 29.

9. “Owners Look to Next Year,” Deseret News, Oct. 1, 1994, accessed August 28, 2024, https://www.deseret.com/1994/10/1/19133899/owners-look-to-next-year/; Congressional Record, 103rd Cong. 2nd sess., August 17, 1994, 22815 (statement of Sen. DeConcini); September 13, 1994, 24495 (statement of Sen. Howard Metzenbaum).

10. Congressional Record, 103rd Cong., 2nd sess., September 30, 1994, 26974–5 (statement of Sen. Durenberger), 26996–7 (statement of Sen. Wofford); August 3, 1994, 19394 (statement of Sen. Specter).

11. S.Amdt. 2601 to H.R.4649, Congressional Record, 103rd Cong., 2nd sess., September 30, 1994, 26977–91; “Nebraska Senator Nixes Vote,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 14, 1994; Staudohar, “Baseball Strike,” 25; Christopher J. Fisher, “The 1994-95 Baseball Strike,” Seton Hall Journal of Sports Law 6 (1996): 379–81; House Committee on the Judiciary, Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption (Part 2): Hearing before the House Subcommittee on Economic and Commercial Law, 103rd Cong., 2nd sess., September 2, 1994.

12. Staudohar, “Baseball Strike,” 26; National Pastime Preservation Act of 1995, S.15, 104th Cong., 1st sess., 1995; John Helyar and David Rogers, "Congress Resists Taking a Swing in Baseball Strike," Wall Street Journal, February 9, 1995.

13. Helyar and Rogers, "Congress Resists Taking a Swing,"; Major League Baseball Restoration Act, S.376, 104th Cong., 1st sess., 1995; Congressional Record, 104th Cong., 1st sess., February 9, 1995, 4258 (statement of Sen. Kennedy).

14. Major League Baseball Antitrust Reform Act of 1995, S.416, 104th Cong. 1st sess., 1995; Professional Baseball Antitrust Reform Act of 1995, S.415, 104th Cong., 1st sess., 1995; Fehr to Hatch, 10 February 1995, Folder 12, Box 574, Daniel P. Moynihan papers, 1765-2003, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Congressional Record, 104th Cong., 1st sess., February 14, 1995, 4823 (statement of Sen. Leahy); Senate Committee on the Judiciary, The Court-Imposed Major League Baseball Antitrust Exemption, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Business Rights and Competition on S.415 and S.416, S.Hrg. 104-682, February 15, 1995, 3, 6, 68–71.

15. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Report to Accompany S.627, Major League Baseball Reform Act of 1995, S.Rpt. 104-231, 104th Cong., 2nd sess., February 6, 1996; Senate Committee on the Judiciary, S. Hrg. 104-682 (1995), 7, 17, 87.

16. Major League Baseball Antitrust Reform Act, S.627, 104th Congress, 1st sess., 1995; “NLRB Votes to Seek an Injunction Against Owners,” Roanoke Times, March 27, 1995.

17. Silverman v. MLB Player Relations Comm., Inc. 880 F. Supp. 246, 261 (SDNY 1995); “Sixtieth Annual Report of the National Labor Relations Board,” National Labor Relations Board (1995), 96–7.

18. Curt Flood Act of 1998, S.53, 105th Cong., 1st sess., 1997.

19. Senator Patrick Leahy, statements on S.53, the Curt Flood Act, 1997–1998, Box 329-05-0073_10, Folder 05, Senator Patrick J. Leahy Papers, University of Vermont.

20. “Likely votes on bill supported by owners & players,” undated (ca. 1997), Senator Leahy and Senator Hatch, 28 February 1997, Fehr to Hatch, 25 July 1997, in Records of the U.S. Senate, 105th Congress, Committee on the Judiciary, Republican Legislative Files, Box 2, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Curt Flood Act of 1998, S.53, 105th Cong., 1st sess., 1997. For more on the impact of the Curt Flood Act, see Janice Rubin, “’Curt Flood Act of 1998’: Application of Federal Antitrust Laws to MLB Players,” Congressional Research Service (CRS) 98-820A, April 12, 2004; Edmund P. Edmonds, “The Curt Flood Act of 1998: A Hollow Gesture After All These Years?” Marquette Sports Law Review 9, No. 2 (Spring 1999): 315–46; and William Basil Tsimpris, “A Question of (Anti)trust: Flood v. Kuhn and the Viability of Major League Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption,” Richmond Journal of Law and the Public Interest (Summer 2004): 69–86; Congressional Record, 105th Cong., 2nd sess., July 30, 1998, 18176.

21. Congressional Record, 105th Cong., 2nd sess., July 30, 1998, 18176.

|

| 202407 01100 Years Since Teapot Dome

July 01, 2024

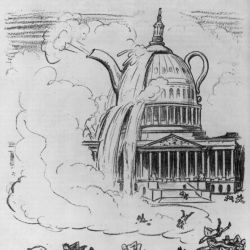

A century ago, in June 1924, the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys released a report, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, that outlined one of the worst breaches of the public trust in American history. The Senate investigation into the scandal, popularly known as Teapot Dome and led by Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, uncovered widespread corruption between government officials and powerful corporate interests. The inquiry serves as a powerful example of effective congressional oversight, highlighting the ability of lawmakers to expose wrongdoing to protect the public interest.

A century ago, in June 1924, the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys released a report, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, that outlined one of the worst breaches of the public trust in American history. The Senate investigation into the scandal, popularly known as Teapot Dome and led by Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, uncovered widespread corruption between government officials and powerful corporate interests. The inquiry serves as a powerful example of effective congressional oversight, highlighting the ability of lawmakers to expose wrongdoing to protect the public interest.

The seeds of the Teapot Dome scandal were planted in the first decade of the 20th century, when President Theodore Roosevelt and conservationists in Congress took steps to protect public lands from unlimited private exploitation. Concerned with ensuring the national government had access to energy resources and anticipating the conversion of the nation’s naval fleet from coal-burning to oil-burning power, Roosevelt instructed the U.S. Geological Survey to survey oil reservoirs beneath public lands. In 1909 President William Howard Taft responded to the Survey’s findings by signing an executive order withdrawing three million acres of public lands in California and Wyoming from private settlement and development and designating portions of these public lands in California, known as Elk Hills and Buena Vista, as naval oil reserves. In 1915 President Woodrow Wilson added a third naval oil reserve in Wyoming, named Teapot Dome after a sandstone rock formation that resembled a teapot. Congress by law in 1920 placed these reserves under the supervision of the secretary of the navy, who was given wide latitude “to conserve, develop, use, and operate the oil reserves” in the national interest.1

In the years after the reserves were created, the nation’s largest oil companies began plotting to obtain leases for drilling. The amount of oil in the reserves, and the money that could be made by extracting it, was staggering. Surveys estimated that the three reserves combined held 435 million barrels of oil, almost equal to the total amount of oil that had been produced in the country to that point. Extracted, those resources were estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, at least a billion in today’s dollars.2

In 1921 Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall was also keenly interested in the reserves. Fall was a former gold and silver prospector and attorney who had been elected to serve as one of New Mexico’s first senators in 1912. Known for his volatile personality and his frontiersman ways—he reportedly often carried a six-shooter pistol—Fall enjoyed the support of prominent industrialists who had helped finance his 1918 re-election campaign and provided backing for Fall’s purchase of a prominent Albuquerque newspaper. In the Senate, Fall became friends with fellow Republican senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio (who had joined the Senate in 1915), the two bonding over whiskey and poker games—then a popular Washington pastime. When Harding was elected president in 1920, he nominated Fall to be his secretary of the interior. Fall had plans to open the nation’s public lands to private development, and he persuaded the president to place the naval reserves under his control. On May 31, 1921, Harding signed an executive order transferring control of the naval reserves from the Navy Department to the Interior Department.3

Rumors swirled for months about Fall’s plans to develop the reserves. On April 12, 1922, Fall offered to his friend Harry F. Sinclair, the head of Sinclair Oil, an exclusive, no-bid lease for the Teapot Dome oil reserves. Intending to keep the deal a secret, Fall locked the contract in his desk and instructed the assistant secretary to tell no one about it. But intrepid reporters soon uncovered the story. On April 14, 1922, the Wall Street Journal ran a front-page exposé detailing the sweetheart deal. The Denver Post was not far behind, offering details about what it called “one of the baldest public land-grabs in history.”4

Independent oil producers saw the press coverage and, angry at not having had an opportunity to bid on the leases, complained to Wyoming Democratic senator John B. Kendrick about the secret negotiations of the Teapot Dome deal. When Kendrick inquired about the details of the lease from the Interior Department, Fall’s subordinates gave him the runaround. On April 15, Kendrick introduced a resolution in the Senate instructing the secretaries of the interior and the navy to inform the Senate about any ongoing negotiations for leases on Teapot Dome. Now under intense pressure, Fall released a statement to the press on April 18 announcing the Teapot Dome lease and disclosing the impending completion of another lease for the Elk Hills reserve to oil baron Edward Doheny and his Pan-American Oil Company. On April 20, Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, a progressive Republican and a leading conservationist in the Senate, introduced a resolution demanding from the Interior Department all documents relating to the negotiation and execution of leases on the naval oil reserves. The Senate amended the resolution to authorize the Committee on Public Lands and Surveys to conduct a full-scale investigation and approved it by unanimous vote (with 38 senators not voting) a week later.5

In early June, Fall submitted to President Harding a 75-page report and thousands of supporting documents detailing the history of the naval oil reserves and the geological data that Fall claimed justified the leases. Harding sent the report to the Senate with a memo stating that all policies regarding the reserves had been reviewed by him and “at all times had my entire approval.”6

The Teapot Dome investigation was slow to get off the ground. The first challenge was getting someone to lead it. While La Follette had been the driving force to authorize the inquiry, he was not a member of the Committee on Public Lands. The Republican chair of the committee was Reed Smoot of Utah, a conservative who was not enthusiastic about pursuing an investigation that could be politically damaging for his party. John Kendrick served on the Public Lands Committee but did not want to take on the task. La Follette and Kendrick persuaded Democrat Thomas Walsh of Montana to lead the investigation.

The son of Irish Catholic immigrants, Walsh had been an attorney in Helena, Montana, before becoming a powerful force in the state’s Democratic Party. Elected to the Senate in 1912, Walsh had a reputation as an able lawyer and a progressive willing to take on the powerful mining interests in his state. Walsh was the most junior member of the minority party on the committee, but the ranking Democrat was leaving the Senate after 1922, and La Follette and Kendrick opted to bypass the other more senior Democrats. Walsh was not a conservationist and had, to that point, been a supporter of opening up public lands—and Native American reservations—for resource exploitation. He was initially reluctant to commit to the investigation, but after some prodding from fellow Montana Democrat Burton K. Wheeler, he agreed in June 1922 to wade in and began reviewing the mountain of documents submitted by Fall.7

Walsh worked through the evidence methodically throughout the summer and fall of 1922, and by early 1923, he began to suspect that Fall had engaged in misconduct. In February 1923, with the Senate set to adjourn in March, the Public Lands Committee set a hearing date for October, a little more than a month before the 68th Congress would convene in December. By the time Walsh returned to Washington in September to begin preparing for the hearing, Albert Fall had resigned from the cabinet to go work for Sinclair, President Harding had died of a heart attack, and Vice President Calvin Coolidge had become president.8

When the hearings began on October 23, 1923, the main question facing the committee was whether Albert Fall was justified in secretly leasing the naval reserves without competitive bidding. Chairman Smoot called the committee to order and then turned over the proceedings to Walsh, who took the lead in questioning witnesses. In the opening round of questioning, Walsh challenged Fall on the legality of Harding transferring control over the naval reserves to him as secretary of the interior and argued that Congress had clearly intended for the secretary of the navy to be the steward of its oil. Fall contended that the president was in his rights to give him responsibility over the reserves. He defended his quick action in granting leases as necessary to prevent the reserves from being depleted by drainage—the intentional depletion of reserves by adjacent landowners. Reports from the Bureau of Mines had indicated that drainage was not a concern, but geologists hired by the committee at the behest of Chairman Smoot disagreed, claiming that the reserves were draining at a rapid rate and that only 25 million barrels of oil remained. Under questioning, Fall defended his selection of Sinclair as a sound business decision and the deal’s secrecy as a matter of national security. Smoot opined that “if the reports of the experts are accepted, the theory that the government made a mistake in leasing this reserve has been exploded.”9

Walsh had other sources, however, that opened up new avenues of investigation. Journalists from Denver and New Mexico—including Carl Magee, who had purchased Fall’s newspaper from him in 1920—told Walsh about a suspicious, abrupt change in Fall’s personal finances. Brought before the committee on November 30, Magee testified that Fall had been cash-poor in 1921 and a decade in arrears on the property taxes of his dilapidated New Mexico ranch. But in June 1922 Fall, suddenly flush with cash, paid his back taxes, purchased neighboring properties, and made substantial improvements to his previously rundown ranch. The burning question became, where did Fall get all of this money?10

By the time Walsh completed his questioning of witnesses in January 1924, he had uncovered suspicious payments made to Fall. Harry Sinclair gave Fall $269,000 in Liberty Bonds and cash a month after signing the Teapot Dome lease. Edward Doheny, to whom Fall awarded the Elk Hills reserve lease, testified that he instructed his son to deliver $100,000 (well over $1 million in today’s money) in cash to Fall “in a little brown satchel,” allegedly as a loan, but one that Fall had lied about and tried to conceal from Walsh and the committee. In a closed committee meeting, Walsh informed his colleagues that he would be introducing a resolution directing the president to appoint a special counsel to bring civil suits to cancel the naval reserve leases and to pursue criminal charges connected to awarding the leases. Republican Irvine Lenroot, now chair of the Public Lands Committee, informed President Coolidge of Walsh’s intentions and urged him to get out in front of the news. On January 27 Coolidge announced his intent to appoint counsel and file charges, and a few days later the Senate passed Walsh’s resolution.11

Walsh was not done with his investigation, however. What had begun in late 1923 as a quiet set of hearings in a small committee room soon became a public sensation with audiences packed into the spacious Caucus Room on the third floor of the Senate Office Building. Walsh recalled Fall to face more questioning, but Fall delayed, claiming ill health. When he finally returned on February 2, 1924, Fall refused to answer any additional questions, claiming his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself and further arguing that the imminent appointment of special prosecutors ended the committee’s authority over the case. When Sinclair came back for more questioning in March, he refused to answer questions as well, though he didn’t bother to cite his Fifth Amendment rights. “There is nothing in any of the facts or circumstances of the lease of Teapot Dome which does or can incriminate me,” he stated. The Senate referred contempt charges against both Fall and Sinclair to the District of Columbia courts.12

The Public Lands Committee concluded its hearings in May 1924, and a bipartisan majority issued its final report in June, signed by Edwin Ladd of North Dakota, who had become committee chair in March. Some senators and representatives, particularly Democrats, criticized the report for its lack of drama and its failure to draw conclusions about the corrupting influence of oil interests in government. Still, the report included additional evidence of corruption, including Sinclair’s payments to buy off rival claimants to the reserves, as well as a $1 million payment to newspaper publishers in exchange for their silence when they discovered the shady circumstances surrounding the Teapot Dome lease.13

The committee noted “rumors” of a broader conspiracy on the part of prominent oil companies to place Harding in the White House and Fall in the Interior Department for the very purpose of exploiting natural resources on public lands but concluded only that “the evidence failed to establish the existence of such a conspiracy.” Five Republicans on the committee, led by Smoot, issued a minority report complaining that the majority had not given them time to review the report and all the supporting evidence. In January 1925, a minority of the committee issued a more substantive report defending many aspects of the Harding administration’s handling of the naval reserves and criticizing Walsh for dedicating space in the report to what it saw as baseless rumors about political conspiracies. Historians who have dug into the scandal have since given these theories more credence.14

Civil and criminal litigation involving the oil reserve leases dragged on for the next six years, with several cases going before the Supreme Court. In the end, the government proved that the leases had been illegally obtained and successfully regained control of the naval reserves. Fall was found guilty of accepting a bribe from Sinclair and sentenced to a year in prison, the first cabinet official in U.S. history to be convicted of a felony. Juries acquitted Sinclair and Doheny on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government, however. Sinclair served prison time for contempt of court—he was found guilty of attempting to intimidate the jury in his criminal trial—and contempt of Congress. The Supreme Court heard his appeal, upheld his conviction, and recognized the Senate’s investigatory power and its authority to compel testimony from witnesses. In another contempt case arising out of a related investigation into Harding administration corruption, the Court held in the McGrain V. Daugherty decision, “We are of opinion that the power of inquiry—with process to enforce it, is an essential and appropriate auxiliary of the legislative function.”15

The Teapot Dome scandal cast a long shadow over American politics, for decades serving as a symbol of the highest form of government corruption. Lawmakers investigating charges of corruption in the decades that followed the scandal would inevitably make the comparison, warning the public that they may find evidence of “another Teapot Dome” or something “worse than Teapot Dome.” In 1950, commenting on the development of the western United States, President Harry Truman stated, “The name Teapot Dome stands as an everlasting symbol of the greed and privilege that underlay one philosophy about the West.” In 1973, as Watergate coverage flooded the national media, some reporters called it “the new Teapot Dome.” “For half a century, [Teapot Dome] has, for many Americans, represented the quintessence of corruption in government,” wrote one correspondent. “Now Teapot Dome has been shoved aside by contemporary events.”16

For the Senate, the Teapot Dome investigation firmly established the authority of Congress to question the executive branch and demand information about its operations. Senator Walsh’s diligent and tenacious search for the truth uncovered corruption and held the government accountable to the people it serves, setting a standard for future Senate investigations to emulate.

Notes

1. Hasia Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” in Congress Investigates: A Critical and Documentary History, vol. 1, eds. Roger Bruns, David Hostetter, and Raymond Smock (Byrd Center for Legislative Studies, 2011), 460; Laston McCartney, The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Bought the Harding Whitehouse and Tried to Steal the Country (New York: Random House, 2019), 28–29, 96.

2. Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves: Hearings Pursuant to S. Res. 282, S. Res. 294, and S. Res. 434, 68th Cong., October 31, 1923, 678. Experts of the time disagreed as to how much oil was held in the reserves. The Bureau of Mines estimated that Teapot Dome held 135 million barrels of oil, for example, but geologists employed by the Committee on Public Lands estimated it at only 12 to 26 million. These estimates turned out to be very low. The Elk Hills reserve alone has yielded more than a billion barrels of oil in the century since. “Elk Hills Is Source of Controversy,” New York Times, April 1, 1975, 10.

3. David Hodges Stratton, Tempest Over Teapot Dome: The Story of Albert B. Fall (Tulsa: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 148–49; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 31–35, 65–67.

4. Quoted in McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 127.

5. S. Res. 277, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 15, 1922; S. Res. 282, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 29, 1922; Congressional Record, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 29, 1922, 6092–97.

6. Naval Reserve Oil Leases, Message from the President of the United States, S. Doc. 67-210, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., June 8, 1922.

7. J. Leonard Bates, Senator Thomas J. Walsh: Law and Public Affairs from TR to FDR (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 201–11; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 160.

8. Bates, Senator Thomas J. Walsh, 210–11.

9. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, October 23, 24, 1923, 175–282; “Experts Uphold Teapot Dome Lease,” New York Times, October 23, 1923, 23, quoted in McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 171.

10. Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” 464; Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, November 30, 1923, 830–43.

11. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, January 24, 1924, 1772; Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” 466–68; Joint Resolution Directing the President to institute and prosecute suits to cancel certain leases of oil lands and incidental contracts, and for other purposes, Public Resolution 68–4, 68th Cong., 1st sess., February 3, 1924, 43 Stat. 5.

12. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, February 2, 1924, 1961–63; March 22, 1924, 2894; Congressional Record, 68th Cong., 1st sess., March 24, 1924, 4790–91.

13. Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, S. Rep. 68-794, 68th Cong., 1st sess., Parts 1 and 2, June 6, 1924.

14. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, S. Rep. 68-794, Part 2, June 6, 1924 and Part 3, January 15, 1925; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 1–73.

15. McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135, 174 (1927); Jake Kobrick, “United States v. Albert B. Fall: The Teapot Dome Scandal,” Federal Judicial Center, accessed June 26, 2024, https://www.fjc.gov/history/cases/famous-federal-trials/us-v-albert-b-fall-teapot-dome-scandal.

16. “Teapot Dome Likeness Seen in Radio Lobby,” Washington Post, January 12, 1937, 24; “War Assets Scandal Seen,” Baltimore Sun, June 19, 1946, 4; “Power Pact Likened to Teapot Dome,” Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1955, 1; “Pledge Given by Truman to Develop West,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1950, 1; “Watergate Joins Teapot Dome in US Scandal Vocabulary,” Christian Science Monitor, May 9, 1973, 7; Lee Roderick and Stephen Stathis, “Today Watergate—Yesterday Teapot Dome,” Christian Science Monitor, July 17, 1973, 9.

|

| 202212 12A Capital Plan: James McMillan, the Senate Park Commission, and the Rediscovery of the National Mall

December 12, 2022

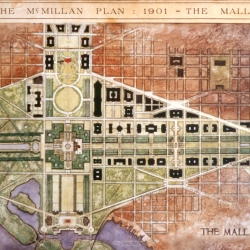

Leading up to the centennial commemoration of Washington, D.C., in 1900, competing plans to redesign and improve the capital city, particularly the public space now known as the National Mall, were being formed. Decades of haphazard development had produced a city that hardly resembled the original plan designed by Pierre L'Enfant in 1791. Among those dedicated to improving the design was Senator James McMillan. As chairman of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, McMillan used his position to promote a far-sighted plan to beautify Washington.

Leading up to the centennial commemoration of Washington, D.C., in 1900, architects, engineers, and other interested parties had begun to develop several competing plans to redesign and improve the capital city, particularly the public space now known as the National Mall. Decades of haphazard development had produced a city that hardly resembled the original plan designed by Pierre Charles L'Enfant in 1791. Among those dedicated to improving the design at the dawn of the 20th century was Michigan senator James McMillan. As chairman of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, McMillan used his position to promote a far-sighted plan to beautify the nation’s capital.

A transportation industry magnate, philanthropist, and leader of the Republican Party machine in Michigan, McMillan came to the Senate in 1889 and quickly established himself as a hard-working and influential senator. He developed strong relationships with his Senate colleagues, founding the “School of Philosophy Club,” a gathering of powerful Republican senators who met at his home to fine tune their legislative agenda. Named chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia in 1891, McMillan immersed himself in work to improve the city’s infrastructure, including the streetcar, railway, and water systems. A longtime patron of the arts and promoter of cultural civic improvements, McMillan also became heavily invested in efforts to develop and beautify the Mall, the city’s central feature, which had greatly expanded with recent efforts to fill in and reclaim the tidal flats of the Potomac River near the Washington Monument.1

Washington, D.C., was unique in that a plan for the nation’s capital city had been designed at its inception. The 1790 Residence Act established a federal district along the Potomac River to include the city as the permanent seat of government. It authorized President George Washington to appoint three commissioners to survey and define the boundaries of the district and to provide for public buildings to accommodate the government by 1800. In 1791, under the auspices of this law, Washington charged L'Enfant, a military engineer who had served on Washington's staff during the Revolutionary War, with creating a plan for the city. L'Enfant proposed a grid system of residential streets with broad diagonal avenues radiating from the principal governmental buildings—the “President’s House” and “Congress House.” The centerpiece of L'Enfant's plan was a Mall, where he envisioned a dedicated public space for learning and recreation—a “place of general resort,” a tree-lined “grand avenue,” surrounded by “play houses, room[s] of assembly, academies and all sort of places as may be attractive to the learned and afford diversion to the idle.” L’Enfant “conceived the capital as the seat of a ‘vast empire,’” one scholar wrote, and the Mall was “the physical and symbolic heart” of his plan.2

During the century that followed, much of L’Enfant’s design for the Mall never materialized. The young republic was not equipped financially or organizationally to fulfill such a plan. L'Enfant's grand and cohesive vision was gradually lost to decentralized and private land development. “Over time, as the view from the west front of the Capitol affirmed,” noted one historian, “the Mall had devolved into a hodgepodge of misplaced buildings, odd structures, and meandering garden paths, all constructed without regard for [L’Enfant’s] intentions.” As another historian wrote, “By 1900 … the Mall had become a chain of individual public parks, each associated with a different Victorian building, most of them built of red brick.” Among the developments that violated L’Enfant’s original design was the terminal of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad at Sixth Street west of the Capitol. The terminal was constructed in 1870 and its tracks cut directly across the Mall, proving to be both an eyesore and a safety concern.3

As the 19th century drew to a close, several groups consisting of local and state authorities as well as members of Congress emerged to discuss plans for a centennial celebration of the capital city. In a February 1900 meeting of the various groups, participants created a special committee of five to review suggestions and make final recommendations and chose Senator McMillan to serve as chairman. McMillan and the committee subsequently proposed a celebration in December 1900 that would include commemorative exercises in both houses of Congress along with a parade and a reception. The committee also recommended a plan to revive L’Enfant’s original vision by converting the entire Mall into a grand boulevard named Centennial Avenue. “Upon looking at the maps which the committee had before it,” McMillan noted, “it was seen that the original plan of Washington, as prepared by Major L’Enfant, provided for just such an avenue, public buildings to be erected on either side of the same.”4

Other organizations and agencies invested in the development of the District criticized the committee’s plan for not being fully developed. Throughout the centennial year, architects and planners from various organizations continued to produce competing designs. The debate culminated in the annual convention of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) held in Washington in December of 1900 to coincide with the centennial celebration. Architects attending the convention presented several additional plans, hoping to draw attention to the subject of beautifying Washington. “It is intended by these papers to call the attention of Congress forcibly to the need of some harmonious scheme to be followed in the future development of Washington,” AIA secretary and noted Capitol historian Glenn Brown wrote. “We propose to have the reading and discussion open to the public and invite all Congressmen and officials to attend."5

Within days, McMillan and other members of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia met with AIA members to craft a joint congressional resolution authorizing the president to appoint a commission “to study and report on the location and grouping of public buildings and the development of the park system in the District of Columbia.” When the House of Representatives showed little interest in the joint resolution, McMillan instead secured passage of a Senate resolution in March 1901. This resolution authorized the Committee on the District of Columbia to form a commission of experts “to consider the subject and report to the Senate plans for the development and improvement of the entire park system of the District of Columbia.” Although McMillan’s resolution focused generally on the city’s park system, his true purpose soon became apparent. “It was obvious from his actions in the following weeks,” noted one historian, “that what he had in mind was nothing less than a comprehensive development plan for all of central Washington in addition to certain studies of Rock Creek and Potomac Parks.”6

The District of Columbia Committee consulted the AIA to determine who should be on the new Senate Park Commission, which became known as the McMillan Commission due to the senator’s prominent role in its creation. The organization recommended architect Daniel Burnham, who had successfully transformed Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, as well as landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who had presented at the AIA convention and urged a return to the “greatness” of L’Enfant’s original plan. McMillan’s longtime aide Charles Moore played an influential role as the commission’s secretary and helped to draft much of the final report. Members of the commission agreed to focus on restoring L’Enfant’s vision for the Mall, and, as expressed by Burnham, “make the very finest plans their minds could conceive.” They set to work surveying the existing landscape of Washington and studying the plethora of proposals for its beautification. In the summer they embarked on a lengthy tour of European cities, “intended as a systematic exploration of the sources of inspiration that had guided L'Enfant’s original plan and an examination of current European treatment of civic architecture and its relationship to open spaces.”7

One of the principal challenges facing the commission was the domineering presence of the railway terminal. As a businessman with lifelong ties to the railroad industry, McMillan assumed a perpetual presence of a railway terminal on the Mall, but members of the commission disagreed. “Mr. Burnham…informed me…that little could be done toward beautifying the Mall as long as the railroad tracks were allowed to cross it," McMillan told a reporter. "The problem then was to get rid of the station." This presented quite a challenge, but the McMillan Commission ultimately succeeded in securing an agreement with the Pennsylvania Railway Company and its subsidiary, the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad, to relocate the terminal. Provided “the Government would meet the company in a spirit which would enable him to justify the move to the stockholders,” the railway company president agreed to consolidate its rail lines to the proposed Union Station terminal north of the Capitol. The station’s design became a core component of the commission’s plan. "This great station forms the grand gateway to the capital, through which every one who comes to or goes from Washington must pass,” the commissioners wrote in their report, calling it “the vestibule" of the capital. “The three great architectural features of a capital city being the halls of legislation, the executive buildings, and the vestibule," the commissioners added, “the style of this building should be equally as dignified as that of the public buildings themselves." The hallmark contribution of the elegantly designed Union Station would become one of the enduring legacies of the Senate Park Commission.8

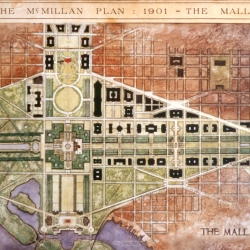

The commission unveiled its plan to an excited crowd at the Corcoran Gallery in January 1902, complete with two scale models—one showing the city’s central core at present, and one displaying the commission’s ambitious plan. The exhibit also featured maps and artists’ sketches of proposed improvements to the city. In its report, the commission emphasized its fundamental allegiance to L’Enfant’s design. "During the century that has elapsed since the foundation of the city the great space known as the Mall…has been diverted from its original purpose and cut into fragments, each portion receiving a separate and individual informal treatment, thus invading what was a single composition," the commissioners wrote. "The original plan…has met universal approval. The departures from that plan are to be regretted and, wherever possible, remedied."9

The scaled models showed the National Mall as an extensive park that stretched from the Capitol to the Potomac River. Stately museums faced each other across a wide lawn. A new monument to Abraham Lincoln anchored the western end, connected by a long reflecting pool to the Washington monument. A decorative memorial bridge spanned the river to Arlington, Virginia. It was a bold and ambitious plan to create a common, national space. Beyond the Mall, the commission developed expansive plans that included a neighborhood park system, scenic parkways, reclamation of the tidal flats in Anacostia, and several public buildings. As their report indicated, the commissioners understood the ambitious nature of the plan and knew that what they conceived would be a guide for the city's development for generations to come. "The task is indeed a stupendous one; it is much greater than any one generation can hope to accomplish," they wrote, noting that their objective was "to prepare … such a plan as shall enable future development to proceed along the lines originally planned—namely, the treatment of the city as a work of civic art."10

James McMillan’s sudden death in August 1902 prevented him from seeing the fruits of his labor. The legacy of the McMillan Commission endured, however, and while its proposed plan has not always been strictly followed, many of its recommendations have become a reality. The plan has served as a guide for the development of Washington, as well as providing a model for city planners across the country. In 1910 Congress established a permanent federal commission, the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, "to ensure that the McMillan Plan for the National Mall was completed with the highest degree of civic art." In 1926 Congress established the National Capital Planning Commission, still in existence, "to ensure the continuation of good planning for the city in the tradition of L'Enfant and McMillan." The McMillan Commission’s report and models “were at once a blueprint for the future of the capital and an early twentieth-century primer for enlightened urban planning,” concluded one historian. McMillan's efforts ultimately succeeded in producing a design that would remain true to L’Enfant’s 1791 vision, while simultaneously reshaping the heart of the city into a modern showplace.11

Notes

1. Geoffrey G. Drutchas, “Gray Eminence in a Gilded Age: The Forgotten Career of Senator James McMillan of Michigan,” Michigan Historical Review 28, no. 2 (Fall 2002): 94; Geoffrey G. Drutchas, "The Man with a Capital Design," Michigan History 86 (March/April 2002): 33–34; Pamela Scott and Antoinette J. Lee, Buildings of the District of Columbia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 76.

2. John W. Reps, Monumental Washington: The Planning and Development of the Capital Center (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967), 17; Jon A. Peterson, "The Senate Park Commission Plan for Washington, D.C.: A New Vision for the Capital and the Nation," in Designing the Nation's Capital: The 1901 Plan for Washington, D.C., ed. Sue Kohler and Pamela Scott (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2006), 2.

3. Tom Lewis, Washington: A History of Our National City (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 247–48; Peterson, "The Senate Park Commission Plan for Washington, D.C.,” 3.

4. Reps, Monumental Washington, 72–74; William V. Cox, comp., Celebration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Establishment of the Seat of Government in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901), 37.

5. Tony P. Wrenn, "The American Institute of Architects Convention of 1900: Its Influence on the Senate Park Commission Plan," in Kohler and Scott, Designing the Nation's Capital, 57.

6. Reps, Monumental Washington, 92–93.

7. Peterson, "The Senate Park Commission Plan for Washington, D.C.,” 6, 14; Wrenn, "The American Institute of Architects Convention of 1900," 62; Drutchas, “Gray Eminence in a Gilded Age," 99–100; Lewis, Washington, 252; Reps, Monumental Washington, 95.

8. “Union Station Plans,” Washington Post, November 12, 1901, 2; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia, S. Rep. 166, 57th Cong., 1st sess., 1902, 29–30.

9. Drutchas, “Gray Eminence in a Gilded Age,” 100; “The New Washington: Plans for Beautifying City Ready for Inspection,” Washington Post, January 15, 1902, 5; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, The Improvement of the Park System, 10, 23.

10. “Plan of New Capital,” Washington Post, January 16, 1902, 11; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, The Improvement of the Park System, 12, 19.

11. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Subcommittee on National Parks, National Mall, S. Hrg. 109-45, April 12, 2005, 4; Lewis, Washington, 255.

|

| 202204 04Treasures from the Senate Archives

April 04, 2022

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the historic records of Senate committees highlighted in this month's “Senate Stories.”

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the historic records of Senate committees highlighted in this month's “Senate Stories.”

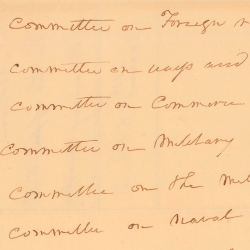

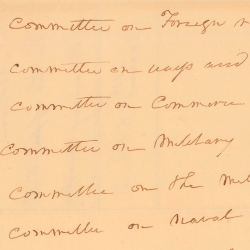

In December 1816, the Senate established its first permanent standing committees. Prior to that time, the Senate had relied on ad hoc or temporary committees to sift and refine legislative proposals, to consider nominations and treaties, and to fulfill other constitutionally designated rights and responsibilities. The demands of a growing nation and a war with Great Britain prompted the Senate to revise its procedures. On December 10, 1816, senators approved a resolution to establish 11 permanent standing committees with jurisdictions over designated areas such as finance, foreign relations, military affairs, commerce, and the judiciary.

The records of these early ad hoc and standing committees, and all subsequent committees, represent the majority of official Senate records preserved and housed at the Center for Legislative Archives at the National Archives and Records Administration. This large collection of archived Senate committee records offers ample evidence of the important work done by each committee.

The Center for Legislative Archives preserves the oldest and most historically significant congressional records in its Treasure Vault, including records created during the First Congress, which convened in 1789. Along with the first Senate Journals, there are bills, war and censure resolutions, petitions, presidential messages, nominations, and proposed constitutional amendments. The simple, handwritten 1816 resolution creating the standing committees is among these precious documents. The fact that these documents were gathered and preserved long before the creation of the federal archives system makes their survival all the more extraordinary.

The following Senate documents from the Treasure Vault highlight the work of three of the Senate's original standing committees: Pensions, Commerce and Manufactures, and Judiciary. Each document captures a moment in time while providing a window into the operation of Senate committees as constitutional government-in-action.

Petition from Mary Colcord, 32nd Congress (1852)

In 1818 Congress passed a pension bill to provide financial support to Revolutionary War veterans. The oversight of this support (sometimes the only form of income for veterans and their families) was managed by the Committee on Pensions, one of the standing committees created in 1816. The committee’s archival records include applications like this one submitted to the Senate in 1852 by 81-year-old Mary Colcord. To document the service of her father, Bradstreet Wiggin, during the Revolutionary War, Colcord submitted the handwritten diary of Samuel Leavitt, a contemporary of her father from the same New Hampshire town who had served in the same company. The diary records Leavitt's service in the New Hampshire militia in 1780. It was given to the committee by Colcord presumably as evidence of her father's service, although she indicates that her father served during a different year. Consequently, the Senate’s archival collection has been enriched by this rare and historic record detailing a common soldier’s experience during the Revolutionary War. Although Colcord's claim, submitted more than 70 years after the war ended, was ultimately rejected by the committee, Congress did continue to pay Revolutionary War pensions as late as 1906.1

Following a congressional reorganization in 1946, the Senate moved the management of all war pensions to the Committee on Finance. In 1970 the Senate formed a Committee on Veterans Affairs and consolidated the oversight of all veterans’ issues, including pensions, under the jurisdiction of the new committee.

Memorial of Inhabitants of Los Angeles County, California, praying for establishment of a port of entry in that county, 31st Congress (1850)

The importance of commerce in national affairs led to creation of the Committee on Commerce and Manufactures in 1816. Regulating commerce is an expressed congressional responsibility, so it is not surprising to find among the committee’s papers this memorial, a form of petition, of the residents of Los Angeles County, California, part of the newly acquired Mexican Cession region, asking for the establishment of a port of entry in that county. This document, dated July 1850, was referred to the Commerce Committee amidst the debate over the Compromise of 1850, which resulted in establishing statehood for California that same year. Rapid progress in technology, communication, and commercial development in the 19th and 20th centuries prompted the Commerce Committee to split into various smaller committees to handle an ever-expanding legislative and oversight caseload. Two legislative reorganizations, in the 1940s and 1970s, consolidated most of these committees under the jurisdiction of today’s Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s message regarding national health, 76th Congress (1939)

On January 23, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a four-page presidential message to Congress calling for the creation of a “national health program … to make available in all parts of our country and for all groups of our people the scientific knowledge and skill at our command to prevent and care for sickness and disability.” Presidential messages, including the annual State of the Union Address, serve as vehicles for the president to raise urgent matters with Congress. The subjects of public health and health care assistance reflect the expansion of the role of the federal government in response to the national crisis of the Great Depression. Perhaps because of the references to science and economic loss, as well as the interstate nature of the proposed program, the message was referred to the Committee on Commerce.

Petition from Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and others, 42nd Congress (1871)

The First Amendment grants individuals the right to petition Congress to redress grievances or to seek the assistance of the government. Petitions allow ordinary citizens to express their views to their elected representatives. Managing these petitions became the responsibility of Senate committees, including the Judiciary Committee, which was established as a permanent committee in 1816 to oversee the courts, judicial proceedings, and constitutional matters. This petition is typical of thousands received by the committee supporting woman suffrage. It is particularly noteworthy because it includes the signatures of leading suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony who ask that they “be permitted in person, and on behalf of the thousands of other women who are petitioning Congress … to be heard … before the Senate and House.” Suffragists first testified before a Senate committee in 1878 and continued to do so until the Senate passed the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919, which granted female suffrage upon ratification in 1920.

President Lyndon B. Johnson's nomination of Thurgood Marshall to be associate justice of the Supreme Court, 90th Congress (1967)

The Senate has the constitutional power to advise and consent on presidential nominations, and Senate committees play an important role in that process. Before the 1860s, the Senate considered most nominations without referring them to a committee for review or investigation, although the Judiciary Committee did consider some nominees as early as the 1830s. In 1868 the Senate adopted rules to provide for more routine referral of nominations to "appropriate committees," but investigations of judicial nominees were rare. By the early 20th century, the Judiciary Committee had become much more integral to the nomination process, and by the mid-to-late 20th century, nominees were regularly testifying before the committee. This featured record of the Judiciary Committee, President Lyndon B. Johnson's 1967 nomination of Thurgood Marshall to be an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, documents the historic appointment of the first African American Supreme Court justice.

First Issue of MAD magazine, from the investigative files of the Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, 82nd Congress (1952)

The creation of standing committees enabled the Senate to better pursue its implied constitutional powers of oversight and investigation to inform legislation or to bring attention to important matters. Since World War II, congressional investigations into allegations of wrongdoing, fiscal mismanagement, national security, corporate malpractice, and social and economic issues of concern have resulted in better legislation, taxpayer savings, consumer protections, and stronger ethics laws. In most cases, standing committees serve as the Senate's principal investigative arm, but the Senate also has entrusted this responsibility to special and select committees.

The broad and extensive nature of these investigations has created an archival record that includes an interesting and unusual assortment of documents and artifacts. Among these is a collection of early 1950s comic books and youth publications, including 12 of the first 13 issues of MAD magazine. Popular films like Nicholas Ray’s 1955 Rebel Without a Cause dramatized public concern about wayward youths and juvenile violence, prompting a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee to launch an inquiry. That investigation explored the role of popular culture, including publications like MAD magazine, in shaping adolescent behaviors and attitudes. The subcommittee continued to investigate the issue of juvenile delinquency for many years.

Illinois senator Everett M. Dirksen once remarked that “floor debate on a bill can be likened to an iceberg…the top shows, but the major part is underneath. The work of the committee is the large part that is not seen by the public.”2 The archived records of Senate committees reflect the behind-the-scenes work of senators and staff. They demonstrate the routine, the historical, the touchingly personal, and even the whimsical nature of committee work. Through these records we gain a better understanding of the history of the Senate and the ever-evolving work of Congress.

Notes

1. History of the Finance Committee, United States Senate, S. Doc. 97-5, 97th Cong., 1st sess., 1981, 47.

2. "What a United States Senator Does, by Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen, Republican Minority Leader," undated, included in the biographical files of the Senate Historical Office.

|