| 202512 16Square 686: A Capitol Hill Neighborhood Transformed

December 16, 2025

At the turn of the 20th century, the blocks around the Capitol were a hub of activity, similar to today, but the landscape was quite different. The office buildings, parks, fountains, and monuments we see today were once densely populated neighborhoods of apartment buildings, row houses, businesses, and store fronts. Between 1900 and 1910, Congress’s growing need for space led to the transformation of neighborhoods around the Capitol, including Square 686, a city block just north of the Capitol.

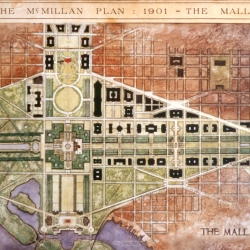

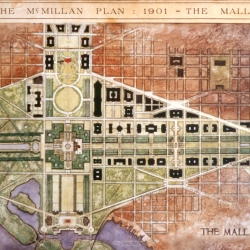

Today, the blocks around the Capitol hum with the movement of tourists, Capitol Hill residents, and members of Congress, their staff, and visitors. Office buildings, parks, fountains, and monuments line the streets, interspersed with row houses and various associations and businesses. At the turn of the 20th century, this land was also a hub of activity, but with many key differences. The densely populated neighborhoods then consisted mostly of apartment buildings, row houses, hotels, hospitals, businesses, store fronts, and churches. Between 1900 and 1910, developers began the transformation of the landscape around the Capitol. To its east, the Pennsylvania Railroad cut and bore a new tunnel directly underneath 1st Street fronting the Library of Congress. Several blocks to the north, planning for a new train terminal, called Union Station, was well underway. To the south, the House’s new office building swallowed an entire city block. And just north of the Capitol, the Senate acquired the thriving city block designated Square 686 and constructed its first office building. 1

The new Senate Office Building was designed to address a critical need. Between 1850 and 1900, 14 states joined the Union, adding 28 senators to a building that was designed to meet the needs of fewer people. The Senate expanded its clerical staff during the same period, in part to support its growing workload, but there was limited workspace for them. Most senators conducted business at their desks in the Senate Chamber. Those who chaired committees gained the use of the Capitol’s larger rooms, which doubled as the chairman’s personal office and accommodated committee staff. These conditions forced senators and staff to use any available space in the Capitol, including alcoves in the attic, corners in the basement, and converted storerooms and closets. In desperation, some senators rented their own office space in nearby buildings. The Senate acquired the Maltby Building—a five-story apartment building located where the modern Taft Carillon now stands—in 1891, but it was not well-maintained. In early 1904, an inspection by Superintendent of the Capitol Elliott Woods identified structural flaws rendering the Maltby Building “extremely hazardous” and “not suited to the uses to which it is now put.”2

By 1902 both the Senate and House had publicly acknowledged intentions to construct office buildings “at no distant day.” The House moved more quickly than the Senate. The Civil Appropriations Act that passed on March 3, 1903, included a $750,000 appropriation to initiate House Office Building excavations. The next year’s appropriation bill, authorized on April 28, 1904, set aside $750,000 for land purchases and $2.25 million for the construction of a Senate office building. The appropriation passed with wide support by a vote of 50-10. Just before the vote, Senator William Stewart of Nevada stated on the Senate floor he was “heartily in favor of the new building … though I shall not be here to enjoy it” due to his pending retirement. Senator William Stone of Missouri acknowledged that only some senators “have excellent quarters in the Capitol … their surroundings are pleasant, congenial, and conducive to good thought and to good work.” In Senator Stone's opinion, a new office building would provide “a nearer approach to equality in the accommodations afforded senators.” Some senators worried about the public perception of this expense. Senator James Berry of Arkansas opposed the measure. “I believe it is wrong,” Berry stated. “I believe it is extravagant … and I believe that if we pass a bill here appropriating money to build offices and committee rooms for the Senate, costing even $33,000 for every Senator here, it will tend to give color to the charge of extravagance which has so often been made against this body.”3

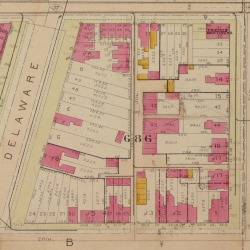

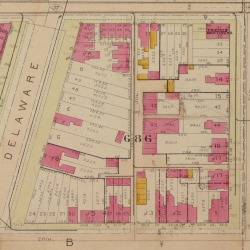

With funding secured, the Senate formed the Senate Building Commission and selected Senators Shelby Cullom of Illinois, Jacob Gallinger of New Hampshire, and Francis Cockrell of Missouri to direct all expenditures, land acquisition, and building construction. They worked closely with Architect of the Capitol Elliott Woods and consulting architect John Carrère of the private firm Carrère and Hastings to develop building designs mirroring those of the new House Office Building. Planners had long decided on Square 686 to the north of the Capitol as the location for the new building. Bounded by B Street, C Street, 1st Street, and Delaware Avenue, Northeast, this block created symmetry with the location of the corresponding House building on the other side of the Capitol. In May 1904 the committee and Woods named Samuel Bieber, a Washington, DC-based banker and real estate expert, to establish price estimates and lead negotiations for land acquisition. In July 1904, when the commission conducted its initial land and title surveys, Square 686 consisted of 45 parcels with 178 owners possessing some financial stake.4

Square 686 was a typical Capitol Hill community. First divided into lots in 1799, people began constructing houses immediately thereafter. An alleyway—Orial Court—bifurcated the square from north to south. According to the 1900 U.S. Census, 300 individuals lived within Square 686, with 252, or 84 percent, renting their homes. Occupants included a cross-section of everyday DC life, such as railroad worker Albert Cox (246 Orial Court), chief of the U.S. Consular Bureau of the State Department and Consul to Canada Robert Chilton, Jr. (225 Delaware Avenue), and Treasury Department clerk Sallie Boaz (48 B Street). At the corner of First and C Streets, the Baltimore Yearly Meeting of Friends, one of the oldest Quaker organizations in America, operated a meeting house. At the center of the block on Delaware Avenue was Casualty Hospital serving the city’s poor. The block was also home to stenographers, bookbinders, teachers, policemen, butchers, masons, speculators, and dairy workers.5

Orial Court in Square 686 was similar to other alleyways found throughout DC during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Photographer Godfrey Frankel captured images of many of these in the 1940s, revealing dilapidated structures and crowded conditions. Yet residents developed strong community and family bonds and considered these alleyways home. While photographs of Orial Court have yet to be located, insurance maps suggest the alley, measuring 15 feet across, had 20 residences. According to the 1900 Census, 88 people lived in the court, predominantly African Americans. In comparison, just one household on the perimeter of the square was headed by an African American individual. The 1900 Census also recorded more than one household within each Orial Court structure, though the census recorded the same pattern in houses on the perimeter. Comparing employment, however, reveals significant differences. Residents of homes on the perimeter of 686 worked in a variety of professions; those calling Orial Court home overwhelmingly worked as domestic help (e.g., “houseworker,” “washerwoman,” “servant”) or as laborers (e.g., “laborer railroad,” “driver lumber,” “whitewasher”).6

Senate-appointed negotiator Samuel Bieber met with Square 686 property owners throughout May 1904. The Washington Post reported on May 1, 1904, that the square’s 45 parcels assessed at “considerably less than $300,000,” so the Senate Building Commission hoped all parcels could be acquired quickly given the $750,000 appropriation. A few weeks later, the commission met to hear updates on Bieber’s negotiations. The Evening Star reported that Bieber’s negotiated prices were “far in excess of the assessed value of the property.” Exactly what those prices were remains unclear, but with Senator Gallinger out of town, Senators Cullom and Cockrell quickly determined “that it was not in the advantage of the government to accept any of the offers” and ordered the architect of the Capitol to proceed with condemnation, a legal process more popularly known as “eminent domain” by which the government purchases private land for public use at a price usually negotiated by a third party, such as an arbitrator or judge.7

In August 1904, the Square 686 condemnation proceedings began. Representatives for the 178 parcel owners and the government’s attorneys appeared in the District of Columbia Supreme Court to negotiate. Following congressional guidance, the court created a three-person committee to navigate the complex condemnation process and appointed three “prominent citizens of the District,” all wealthy men: Robert I. Fleming (architect and member of the D.C. Board of Commissioners), James F. Oyster (businessman and civic leader), and H. Rozier Dulaney (real estate agent). Throughout August and September, they toured Square 686 and held hearings to receive testimony from parcel owners. Their report, submitted in October 1904, identified 45 sale agreements totaling $746,111. The Senate Building Commission quickly approved the report, and funds were then distributed in December. All residents, including both owners and renters, vacated Square 686 by January 1905.8

Only one recorded instance survives of pushback from a Square 686 resident. W. H. Smith, a tenant living on the third floor of 28 B Street NE petitioned the court on August 9, 1904, that “by means of the condemnation and purchase of the square by the Federal Government, he will be forced to vacate the premises which he has peaceably and satisfactorily occupied as stated, subjecting him to both trouble and expense, with little or no hope of finding another apartment that will be as convenient or comfortable.” Smith, a Government Printing Office employee, claimed $500 to account for potential damage to furniture and moving costs. Surviving records do not indicate whether Smith received payment, though by 1906 he was residing in a rental unit south of the Capitol on New Jersey Avenue SE, directly across the street from the construction of the new House Office Building.9

Following the condemnation proceedings, at least one Square 686 parcel owner—Casualty Hospital—seemed to welcome the change. The hospital building, a three-story brick converted residence, was woefully insufficient according to the hospital’s board of directors. During the first three months of 1904, for example, hospital staff treated nearly 5,000 individuals, including 411 emergency cases and 115 surgeries within what The Evening Star described as “the present ancient structure.” The same article reported that directors desired “a modern hospital fitted out with the latest medical and surgical appliances, and an ambulance … [given] the necessity for such an establishment … in the eastern part of the city.” Within a year, Casualty Hospital reopened in a newly renovated facility six blocks to the east on Massachusetts Avenue, NE. Other parcel owners successfully relocated as well. Even though the Baltimore Yearly Meeting of Friends had just spent $2,000 in February 1904 to upgrade to their auditorium with a new floor, brick repairs, and a gallery extension, the group used the $21,800 received from condemnation to move to Columbia Heights in 1905.10

By the summer of 1905, Square 686 had been reduced to rubble, dirt, and a “dinkie railroad”—a short temporary locomotive line—that carried refuse north to the future site of Union Station. The once vibrant community of private residences and businesses would soon be replaced by the Senate Office Building, which opened in 1909, and the accompanying hustle and bustle of senators, staff, and visitors. Other construction projects followed over the next 70 years as the Senate cleared additional land to make way for new parks, monuments, and office buildings. These developments altered the Capitol Hill landscape to support the critical work of the United States Senate.11

Notes

1. “Cannon House Office Building,” Architect of the Capitol, accessed December 5, 2025, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/buildings-grounds/house-office-buildings/cannon; Thomas S. Hines, Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner (University of Chicago Press, 2009), 284–8; Building Conservation Associates, “Washington Union Station Historic Preservation Plan: Volume I” (2015), 22, accessed December 5, 2025, https://www.usrcdc.com/projects/historic-preservation-plan/; “Opposed to Open Cut,” Washington Post, March 3, 1905.

2. “Maltby Building,” U.S. Senate Historical Office, accessed December 5, 2025, https://www.senate.gov/about/historic-buildings-spaces/office-buildings/maltby-building.htm.

3. Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia, S. Rep. 57-166, 57th Cong., 1st sess., January 15, 1902; Shelby M. Cullom, Fifty Years of Public Service (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1911), 347–8; Henry A. Converse, “The Life and Services of Shelby M. Cullom” in Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society for the Year 1914 (Illinois State Historical Library, 1914); “For House Offices and Extension to Capitol,” Washington Times, February 12, 1903; “Consult Engineers on Office Building Site,” Washington Times, March 7, 1903; “The House Office Building Criticized,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 16, 1903; ”Waiting for Titles,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), June 11, 1903; “Is Not Privileged,” Evening Star, April 27, 1904; “An Office Building,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 21, 1904; Congressional Record, 58th Cong., 2nd sess., April 19, 1904, 5083–4, 5170–1; William C. Allen, History of the United States Capitol (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 378–81.

4. “Office Building for the Senate,” Washington Times, April 15 1904; “Dolliver Talks About the Trusts,” Age-Herald (Birmingham, AL), April 21, 1904; “Real Estate Market,” Washington Post, May 1, 1904; “Extension of the Capitol,” Baltimore Sun, May 1, 1904; “Mr. Bieber Named,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), May 4, 1904; “District Dock. 2, No. 624,” July 18, 1904, Case 624, Box 55, District Court Case Files Relating to Admiralty and Condemnation Proceedings, Record Group 21: Records of the District Courts of the United States, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

5. Population Schedule for Washington, D.C., Enumeration District No. 118, Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900, Record Group 29: Records of the Bureau of the Census, Microfilm Publication T623, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC; Robert S. Chilton Papers 1, finding aid, Georgetown University Library Booth Family Center for Special Collections, accessed December 5, 2025, https://findingaids.library.georgetown.edu/repositories/15/resources/10018.

6. Godfrey Frankel, In the Alleys: Kids in the Shadow of the Capitol (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995); Population Schedule for Washington, D.C., Enumeration District No. 118; George William Baist, Baist's Real Estate Atlas of Surveys of Washington, District of Columbia: Complete in Four Volumes, 1913, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

7. “Real Estate Market,” Washington Post, May 1, 1904; Susan Mandel, “The Lincoln Conspirator,” Washington Post, February 3, 2008; “Price Regarded as High,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), May 25, 1904.

8. “Court Acts Upon Senate Building Site,” Washington Times, August 10, 1904; “Preliminary Steps,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 10, 1904; “Commission Named,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 11, 1904; “District Court,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 12, 1904; “Hearing of Testimony,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 22, 1904; Robert Isaac Fleming Papers, Finding Aid, The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., accessed December 5, 2025, https://dchistory.catalogaccess.com/archives/104088; “District Dock. 2, No. 624,” “Certificate of Publication”; “Senate Office Site,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 12, 1904; “The Award Approved,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 22, 1904; “In the District,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 22, 1904; “Distributing Funds to Pay for Site,” Washington Times, December 27, 1904.

9. “District Dock. 2, No. 624,” W. H. Smith to Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, August 9, 1904, December 5, 1904; Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia (Washington D.C.: R.L. Polk & Co., 1903); 895; Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia (Washington D.C.: R.L. Polk & Co., 1906), 1043.

10. “Casualty Hospital Report,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 23, 1904; “Capitol Hill Historic District (1976 Boundary Increase),” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, January 26, 1976, D.C. Office of Planning, accessed December 5, 2025, https://planning.dc.gov/publication/capitol-hill-historic-district; “Permit No. 1136,” Feb. 11 to Mar. 8, 1904, Permits 1135 – 1251, Record Group 351: Records of the Government of the District of Columbia, Series: Building Permits, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC; “St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church South,” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form:, November 30, 2017, D.C. Office of Planning, accessed December 5, 2025, https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/publication/attachments/St%20Pauls%20Methodist%20Episcopal%20Church%20South%20Nomination_1.pdf.

11. “Delay in the Work,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), December 1, 1904; “Excavations Begun,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), May 1, 1905.

|

| 202503 25The Senate Spares the Belmont House

March 25, 2025

As the Senate sought to expand its office space during the mid-20th century, many neighboring structures were targeted for demolition. One such example was the historic Belmont House, headquarters of the National Woman’s Party. Ultimately, through the efforts of advocates, staffers, and senators themselves, the Senate came to see the Belmont House, with its unique connection to women's history, as a historic structure worthy of preservation.

In the early 1950s, Washington D.C.’s “Square 725” was a vibrant city block comprising private residences, organizations, and businesses just blocks to the northeast of the Capitol. Dozens of individuals and families called this place home. Schott’s Alley cut across the heart of Square 725 lined on either side by about 10 residences, some of which were renovated into “deluxe living quarters” by developers in 1954. Locals shopped for groceries at Lucille’s Delicatessen, located at 135 C Street NE. Two doors down at 131 C. Street NE, Rev. Alfred Terry held religious services on Sundays at the First Spiritualist Church and sponsored seances and classes. The Galena and The Merrick, at 132 and 138 B. Street NE respectively, were both lodging homes primarily for women who worked as clerks, stenographers, and typists, many of whom were employed by the Senate. In other words, Square 725 was a lively community much like any other in the District. The U.S. Senate was about to dramatically change it.1

Following World War II, senators sought to modernize their institution, approving the Legislative Reorganization Act in 1946 that provided for the hiring of professional, non-partisan staff. It wasn’t long before the Senate needed additional office space to accommodate that staff. Planning began shortly thereafter to erect a second office building (the first Senate Office Building—today's Russell Senate Office Building—opened in 1909), and the logical location was Square 725. Following the pattern established when the first Senate Office Building had been constructed, the Senate planned to purchase the land and demolish the existing neighborhood to make way for a new structure. By the end of 1949, the Senate had acquired the western half of Square 725, cleared much of the land, and approved a new building design, but construction was delayed. The groundbreaking ceremony for the Senate’s new office building finally took place on January 26, 1955. While waiting on construction, senators discussed acquiring and clearing the entirety of Square 725 for potential building expansion at a later date.

Clearing Square 725, however, would not be so easy. At the corner of Constitution Avenue and 2nd Street NE sat the historic Belmont House, headquarters for the National Woman’s Party (NWP) since 1929. The NWP, one of the most influential American women’s rights organizations of the early 20th century, was credited with helping to secure women’s suffrage and protections from employment discrimination. Belmont House had also been the scene of historic events connected to the Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812. Preservationists considered the structure to be “one of the cornerstones of American heritage on Capitol Hill.”2

The Washington Post reported in early 1956 that the most likely outcome for the entire square was full acquisition by the Senate, potentially by seizure under eminent domain laws, with all structures eventually to be demolished. With legislation for full acquisition pending, the Senate Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds of the Committee on Public Works held hearings in May 1956 to hear from some of the affected parties. Recognizing that the Belmont House was endangered, the NWP rallied in opposition and strongly protested in their testimony.3

During the first moments of the 1956 hearings, Senator Carl Hayden of Arizona, a champion of women’s rights and suffrage even before his Senate service, testified as a witness and offered to amend the pending legislation to exclude the Belmont House, but only if “there should be a quantity of proof before the committee as to the historical value of the property.” In response to Hayden’s offer, nearly a dozen NWP supporters testified to the structure’s unique history, including Augusta Wood Dale, widow of Senator Porter Dale and former Belmont House owner. Most witnesses focused on the house’s age and its connection to early American heritage.4

Dating to about 1800, the house was rented from 1801 to 1813 by Albert Gallatin, secretary of the treasury under President Thomas Jefferson and primary negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty. During the War of 1812, the house gained some notoriety, as conveyed by several witnesses who told the story of shots being fired from the house upon advancing British troops who then burned part of the structure before moving on to burn the Capitol. Several witnesses testified to the historical integrity of the structure and lamented the destruction of historic buildings throughout the District, including the Old Brick Capitol that had been razed to make way for the Supreme Court Building in the 1930s. All throughout the testimony, the building’s connection to the NWP and women’s history was hardly mentioned.5

Despite the testimony at the 1956 hearings demonstrating the historical value of Belmont House, the legislation to acquire Square 725 continued to threaten the house’s existence for the next two years. NWP leader Alice Paul, speaking to the Washington Post, expressed her frustration with the long delay, equating the ongoing threat of demolition to congressional harassment. With full Square 725 acquisition still pending on June 23, 1958, Senator Dennis Chavez of New Mexico, chair of the Committee on Public Works, finally introduced an amendment, penned by Senator Hayden, that excluded seven lots, described as “property in Schott’s Alley and other property,” from the proposed acquisition. In a statement accompanying his amendment, Senator Hayden indicated that he understood acquisition would proceed if “the bill is amended so as to exclude the real property occupied by the NWP.” With the amendment adopted, the bill passed easily. The Senate had spared the Belmont House, for now.6

In 1967, less than 10 years after the opening of the Senate’s second office building (later named the Dirksen Senate Office Building), Senator Jennings Randolph of West Virginia proclaimed that the Senate was “long since past a critical stage” regarding office space. A Committee on Public Works survey concluded that 72 senators and 24 committees required additional space and recommended immediate acquisition of the remainder of Square 725—including portions of the NWP’s property—to build a third office building (later named the Hart Senate Office Building). The Belmont House was again in demolition crosshairs.7

The Senate quietly moved forward with these plans and, unbeknownst to the NWP, passed a bill to acquire the remaining sections of Square 725 by a vote of 42-33 in April 1968. The Senate bill called for condemning two-thirds of the Belmont House property to make way for an access driveway for the newest Senate office building. When the House considered the bill that September, NWP leadership finally learned of the plan and rushed to make their voices heard. NWP leaders fired off telegrams, visited House of Representative offices, and spoke directly to the media over the course of about two weeks as the bill neared House approval. Joining the NWP in its crusade to save Belmont House was “a new coalition of college girls and radicals,” according to the Washington Post, including the newly created National Organization of Women and members of the National Women’s Liberation Group. The house’s connection to women’s history was now front and center. To the relief of NWP leadership, the House rejected the legislation, and the Belmont House was spared for a second time.8

The Belmont House’s future brightened significantly between 1972 and 1974. First, Congress authorized the purchase of some of the NWP’s peripheral property, providing funds for the organization to discharge its debts. Next, the National Capital Planning Commission worked with the National Park Service (NPS) to have the house listed on the National Register of Historical Places, thus formally recognizing the structure’s national historical significance for the first time. Writing in support of the listing, an unsigned NPS commenter noted, “They’ve torn down all adjacent housing and I’m sure that they’ve got this in mind next.” The Belmont House also benefitted from increased attention to women’s rights. In 1972 the Senate overwhelmingly approved the Equal Rights Amendment, to prohibit discrimination on account of sex, by a vote of 84-8. The House had already passed the bill, and it was sent to the states for ratification.9

In 1974 a Senate staff member kickstarted legislation to permanently save the Belmont House. Then-NWP National Chairman Elizabeth Chittick approached Frankie Sue Del Papa, a law student in her third year working as a staff member in the office of Senator Alan Bible of Nevada. Del Papa created a law school project, with the blessing of Senator Bible, to draft legislation that would, in her words, “save the Sewall-Belmont House from eminent domain.” Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington introduced the legislation on March 19, 1974, and called for its passage because “the women’s rights movement is not itself represented” within the National Park Service. Senator Bible wholly supported the bill and, as chairman of the Subcommittee on Parks and Recreation of the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, scheduled hearings for May 31, 1974.10

Many senators testified at the subcommittee hearing in favor of permanently protecting the Belmont House because of its connections to women’s history. Senator Jackson provided the context and impetus for such action: “What a fitting statement by Congress to create a women’s history monument as the Equal Rights Amendment marched towards certain ratification.” Senator Howard Metzenbaum of Ohio, who co-sponsored the bill, echoed this sentiment while also drawing a metaphor about the women’s rights movement and the Belmont House itself: “In this house, much of the history of the woman's movement was made, fragile gains cementing one another, somewhat as the brick walls of the kitchen were laid with mortar made from oyster shells.” Del Papa’s testimony underscored the importance of the Belmont house as a symbol of women’s history. “Previous Senate committees have not always been so thoughtful of this neighboring historic house,” she explained, reminding senators the house was nearly razed in the 1950s, before praising “some farsighted Senators [who] sought to preserve for posterity this symbol of, and monument to, the women’s rights movement.”11

On October 4, 1974, a favorable report from Senator Bible of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs recommended passage of an NPS omnibus bill creating six park units, amended to include the “Sewall-Belmont House National Historical Site” as a “cooperative agreement to assist in the preservation and interpretation of such house.” Four days later, the Senate passed the measure without debate, and it was signed into law by President Gerald Ford later that month. According to Del Papa, significant support in the Senate came from Senator Bible’s direct appeal to other members. 12

Today the Belmont House stands proudly at the corner of 2nd Street NE and Constitution Avenue—the only remaining structure of the once vibrant Square 725. Sitting at the Capitol’s periphery since 1800, the Belmont House was associated with historically significant events and people, but it was its connection to the women’s suffrage movement that ultimately saved it from the wrecking ball. According to Elizabeth Chittick, the Belmont House is “a place where women may find their identity with the history of the past in their march for equal rights.” Senator Jackson brought this same sentiment to the Senate floor in 1974, stating the Belmont House represented “contributions and efforts which women have made to the development of this nation and in awakening social conscience for human rights.” This perspective took years to form within the Senate, but largely thanks to efforts by the NWP and senators who listened, the Belmont House became central to American history and heritage at a particularly significant time for the advancement of women’s rights. Today, under the protections of the National Park Service, the Belmont House, now the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, serves as a reminder of that powerful political heritage. 13

Notes

1. Senate Committee on Public Works, Extension of Capitol Grounds: Hearings on S.3704, 84th Cong., 2nd sess., May 21–22, 1956 (hereafter referred to as “1956 Hearings”), 9; Population Schedule for Washington D.C., ED 1-785, Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950, Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; “Rooms Furnished-N.E.,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), August 15, 1950.

2. Note that the “Belmont House” has been known by many names over the years. As of 2025, it is formally known as the “Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument.” It has also been known as the Sewall House (1800–1929), the Alva Belmont House (1929–1972), and the Sewall-Belmont House and Museum (1972–2016). This essay refers to the structure as the “Belmont House” for simplicity and because this was the terminology typically used by senators from the 1940s through the 1970s; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, Hearing held before Subcommittee on Fiscal Affairs of the Committee on the District of Columbia, S.2306, Relating to the Exemption of the National Woman’s Party, Inc. from Taxation in D.C., 86th Cong., 2nd sess., January 19, 1960 (hereafter referred to as “1960 Hearing”), 14–19.

3. “Senate Unit Votes $4.5 million to Buy 1 1/2 Blocks Near ‘Hill’ Area,” Washington Post and Times Herald, February 9, 1956; 1960 Hearing, 25; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia, S. Rep. 57-166, 57th Cong., 1st sess., 1902, 37–40; Quinn Evans, Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument: Historic Resource Study, National Park Service (Jan. 2021): 3–51; Enlarging of the Capitol Grounds: The Final Report of the Commission for Enlarging of the Capitol Grounds, S.Doc 76-251, 76th Cong., 3rd sess., 1943, 493.

4. 1956 Hearings, 6; House Committee on Election of President, Vice President, and Representatives in Congress, Woman Suffrage: Hearings on H.R.26950, 62nd Cong., 3rd sess., January 31, 1913; Ross Richard Rice, Carl Hayden: Builder of the American West (University of Michigan, 1994), 46.

5. 1956 Hearings, 34, 54–57; Wes Barthelmes, “Capitol Grounds Expansion Opposed,” Washington Post and Times Herald, May 22, 1956.

6. Paul Sampson, “New Belmont House War,” Washington Post and Times Herald, February 19, 1957; Richard L. Lyons, “Belmont House Women in Arms,” Washington Post and Times Herald, March 29, 1957; “$965,000 Voted in Parking Bill,” Washington Post and Times Herald, January 30, 1958; Congressional Record, 85th Cong., 2nd sess., July 17, 1958, 11943.

7. Senate Committee on Public Works, Authorizing for Extension of New Senate Office Building Site, S. Rep 90-735, 90th Cong., 1st sess., November 8, 1967.

8. Emma Guffey Miller and Alice Paul to Senator Everett Jordan, September 17, 1969; Emma Guffey Miller and Alice Paul to Hale Boggs, September 17, 1968; Emma Guffey Miller to John W. McCormach, September 24, 1968; Mary Birckhead and Alice Paul to Charles E. Bennett, September 26, 1968; Alice Paul to Emma Guffey Miller, September 26, 1968, NWP Papers, Part 1, Section C: 1945–1974 (Sep. 1 – Sep. 30, 1968); "An Act to Authorize the Extension of the Additional Senate Office Building Site,” S.2484 90th Cong., 2nd sess., 1967; “Senate Office Building,” CQ Almanac 1968 24 (1969); ”One House Saves Another,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1968; ”Delay in Belmont House Bill,” Los Angeles Times, September 24, 1968; ”Senate Plan Brings Ringing Protests,” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1968.

9. James Banks to Elizabeth Chittick, July 16, 1973, NWP Papers, Part 1, Section C: 1945–1974 (Jul. 1 – Jul. 31, 1973); Suzanne Ganschinietz, National Register of Historic Places nomination: Sewell-Belmont House, Washington, D.C., June 16, 1972.

10. “Frankie Sue Del Papa,” Nevada Women’s History Project, accessed March 14, 2025, https://nevadawomen.org/del-papa-frankie-sue/.

11. Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Sewall-Belmont House National Historic Site, Hearing on S.3188, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., May 31, 1974, 73.

12. An Act to provide for the establishment of the Clara Barton National Historic Site, Maryland; John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon; Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota; Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Massachusetts; Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama; and Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, New York; and for other purposes, Public Law 93-486, 93rd Cong., 2nd. Sess., October 26, 1974, 88 Stat. 1463; Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Report on Providing for the Establishment of Clara Barton National Historic Site, Md., and Other Historic Sites and Memorials, S. Rep. 93-1233, 93rd Cong., 2nd. sess., October 4, 1974; Senate Committee on Public Works, Addition to the Dirksen Senate Office Building, Hearing, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., 1974, 49; Congressional Record, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., October 8, 1974, 34297–401; Wauhillau LaHay, “She’s the Happiest Woman in Washington,” NWP Papers, Group II: Printed Matter, 1850–1974.

13. Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Hearing on S.3188, 18; Dorothy McCardle, “Sen. Jackson Seeks Shrine for Women's Rights Movement,” Washington Post, April 14, 1974.

|

| 202407 19Historical Images of the Library of Congress in the U.S. Capitol

July 19, 2024

For nearly a century, the Library of Congress made its home in the U.S. Capitol (1800–1897). Beginning in 1824, it occupied a grand, three-story space to the west of the Capitol Rotunda. After the Library of Congress moved into its own building in 1897, its former location in the Capitol was completely dismantled. Historical prints and photographs in the U.S. Senate Collection can help us to remember and revisit spaces—like the library—that are no longer extant but were once considered among the building’s architectural gems.

Of the many historical images in the U.S. Senate Collection that depict the Library of Congress in the Capitol Building, one 1897 Harper’s Weekly illustration stands out for its particularly chaotic depiction of the space. As the caption indicates, the scene portrays the institution’s “present congested condition” in the months just prior to the library’s relocation to its own building across the street. The illustration by artist William Bengough teems with visitors. Men and women, young and old, occupy every seat visible in the image and navigate mountainous piles of books and papers stacked high on the floor and on nearly every horizontal surface. In the background, the library’s innovative cast-iron architecture can be glimpsed above and behind the disorder of the central vignette. Though the library soared some 38-feet high, Bengough crops the vertical space, contributing to the claustrophobic scene. For all of this visual confusion, however, the illustration reveals at least three truths about the Library of Congress during its years in the Capitol (1800–1897): 1) it exceeded its founding purpose and served as an important public resource, 2) the library rapidly outgrew its physical spaces as its collections expanded, and 3) it was one of the Capitol’s architectural gems.

At the time of its founding, the library was intended to serve a narrower, albeit significant, purpose. Section 5 of the April 24, 1800, act relocating the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to Washington established the library. It appropriated $5,000 “for the purchase of books as may be necessary for the use of Congress at the said city of Washington, and for fitting up a suitable apartment [in the Capitol] for containing them.” Though its collections started small and its intended audience was “both houses of Congress and the members thereof,” within its first decades in the Capitol, the library’s holdings had grown in size and public importance. At the same time, its “suitable apartment” in the building grew in size and architectural stature.1

Bengough’s illustration shows the last of several Capitol spaces occupied by the Library of Congress. The library’s first two decades required it to be portable and adaptable. Though the founding act called for “fitting up a suitable apartment” to house the library’s collections, its books were first stored in the office of the Clerk of the Senate. It was not until 1802 that the library’s collections of 964 volumes and 9 maps were relocated to a large, two-story room in the northwest corner of the Capitol, a space that had most recently served as a temporary House Chamber. Just three years after moving into the new location, however, the library was asked to remove its collections to a committee room on the south side of the library so that the House could reconvene in the space. In a November 1808 report, architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who was hired by President Thomas Jefferson to oversee construction of the Capitol, observed that the committee room was already “much too small” and that the books were “piled up in heaps,” a situation that would certainly cause the “utmost embarrassment.”2

Despite Latrobe’s concerns, it was not until a devastating fire set by British troops at the Capitol on August 24, 1814, destroyed much of the building and completely consumed the library that it finally received a dedicated space. Congress acted quickly to replenish the Library of Congress’s holdings by purchasing the personal library of President Jefferson, but it took nearly a decade to rebuild the library itself. Congress asked Latrobe to create more committee rooms in the building’s north wing for the Senate’s use, and the architect decided to repurpose the space previously occupied by the library to fulfill Congress’s request. His March 1817 plan of the Capitol’s principal floor relocated the library to the west side of the Capitol’s center building. Architect Charles Bulfinch, who stepped in after Latrobe’s November 1817 resignation, defined the new library’s design and saw it to completion. Opened on August 17, 1824, the new library was widely recognized for its grandeur and refinement. As one commentator observed soon after the room opened, “The new Library Room is admitted, by all who see it, to be, on the whole, the most beautiful apartment in the building. Its decorations are remarkably chaste and elegant, and the architecture of the whole displays a great deal of taste.”3

The only known image of Bulfinch’s design for the Library of Congress, an 1832 view by architect Alexander Jackson Davis and artist Stephen Gimber, emphasizes the library’s impressive architecture and portrays it as a comfortable space for visitors. Four deep alcoves filled with books, as well as a second-story gallery with additional book storage, are visible along the left-hand side of the image. Monumental columns frame the library’s east and west entrances. The room is well appointed with large sofas, reading tables, and side chairs. One of the neoclassical iron stoves designed by Bulfinch to heat the room is visible in the image, towering over the library’s patrons. Architect Robert Mills remarked upon the public use of the space in 1834, “The valuable privileges afforded all, whether residents or strangers, who come properly introduced, are properly appreciated; for the room is usually well filled, during the hours it is accessible, both with ladies and gentlemen.” Thus, it is clear by this time that the library was frequently used by men and women of the public, albeit with the restriction that they “come properly introduced.”4

Despite its many amenities, Bulfinch’s library was largely constructed of wood, and the threat of fire was a persistent source of concern. The space survived one on December 22, 1825—scarcely 16 months after it had opened—when a patron left a candle burning in the gallery after the library closed for the evening. The conflagration destroyed many of the books on the gallery level (most of which were duplicates of books stored elsewhere), but firefighters were able to extinguish the flames before they reached the ceiling’s large wooden trusses. This contained the fire to the library and prevented its spread to the Capitol’s dome. This near-disaster led to discussions about how to fire-proof the library, but the required fixes were deemed prohibitively expensive. Unfortunately, a second fire, sparked by a faulty flue leading from a fireplace in a room below, completely destroyed the library on December 24, 1851. Some 35,000 volumes—approximately three-fifths of the collections—as well as many priceless artworks burned. News of the fire traveled quickly, and the Cleveland Daily Herald reported—even before the fire had been extinguished—that the destruction of the library “cannot be regarded otherwise than as a great national calamity.” Though it had been founded as a library for the use of Congress, by the time of the 1851 fire, according to the newspaper, “it had become eminently creditable as a National Library.”5

Moving rapidly to rebuild, Congress called upon architect Thomas U. Walter, who was working on the Capitol extension, to design the world’s first completely fireproof library. With amazing speed, just 24 days after the fire, Walter provided architectural plans, sections, and elevations for a new library that was revolutionary in its use of cast-iron, a strong, noncombustible material that could be shaped into delicately ornamented panels. The library had three stories of tiered alcoves and galleries with cast-iron shelving. Recessed cast-iron semicircular staircases located at each end of the room enabled patrons to ascend to the upper levels. Large foliated pendants supported the weight of the cast-iron ceiling, the first in the United States to be constructed of this material. Marble, another fireproof medium, was selected for the flooring. With a robust appropriation of $75,000 from Congress, the library, as Harper’s New Monthly Magazine described it, “rose, phoenix-like, from its ashes.” A “large number of ladies and gentlemen” reportedly gathered for the library’s public reopening on August 23, 1853, and spectators were amazed by its iron architecture, describing it as “unsurpassed for its beauty and elegance.”6

Two large extensions added in 1867 to the north and south ends of the main hall tripled the library’s physical size and greatly expanded its capacity from 38,000 to 134,000 volumes. Such a substantial expansion was necessary to accommodate the rapid growth of the collections, which more than quadrupled in size from a reported 86,414 volumes in 1864 to 374,022 volumes by 1879. This tremendous increase was driven by several significant acquisitions and purchases, including a large transfer from the Smithsonian Institution library in 1866, as well as the 1870 Copyright Act, which required all materials copyrighted in the United States to be deposited with the Library of Congress.7

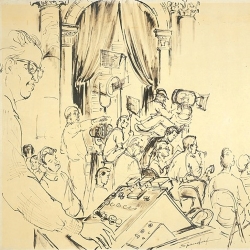

Throughout this period, commentators remarked on the library’s popularity with the public. In 1872 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine reported that it was almost impossible to “visit the library at any time when its doors are open without finding from ten to fifty citizens seated at the reading-tables, where all can peruse such books as they may request to have brought to them from the shelves.” The accompanying illustration presents a view of the library, looking down from the lower gallery. It shows patrons using the library’s collections at each level. People are depicted reading, but also socializing (as in the group of three chatting prominently in the foreground) and people-watching (as in the woman pictured on the right-hand side of the image, who gazes toward a man on the opposite side of the library at the left). The article emphasizes the public’s generous access to the Library of Congress and even claims, “The library is thus thrown open to any one [sic] and every one, without any formality of admission or any restriction.”8

Illustrators had the advantage of being able to represent the social aspects of visitors’ engagement with the library in ways not easily achieved in other media. Though the space was often reproduced photographically in popular stereographs during the late 19th century, the limitations of shutter speed during this period meant that people using the library—who possibly weren’t even aware that a photograph was being taken—appear blurry and indistinct. A stereograph of the Library of Congress published by J. F. Jarvis exemplifies the ghostly appearance of the library’s patrons. Though many are seated at reading tables, they elude the camera’s quest for fixity by flipping newspaper pages and shifting in their seats. The fleeting impressions of people in the space contrast with the tremendous detail that the camera captures of the library’s static and seemingly permanent fireproof architecture.

A close examination of the first gallery level of the library in this stereograph reveals piles of books and papers stacked high on the gallery floor. Once again, the library was stretched beyond capacity. By 1875 Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford reported that the institution had run out of shelf space, and that books, maps, and other collection items were “being piled upon the floor in all directions.” Four years prior, anticipating the spatial limitations of the Capitol, Spofford had proposed constructing a dedicated building for the Library of Congress in a separate location. In 1886 Congress authorized construction of what is now the Library of Congress’s Jefferson Building across the street from the Capitol.9

The Library of Congress remained in the Capitol until its new building opened on November 1, 1897. The large cast-iron rooms formerly occupied by the library remained in place until June 1900, when Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the Architect of the Capitol to reconstruct the space into three floors, with rooms on two of the floors split evenly between the House and the Senate and the third floor turned into a shared reference library. The ironwork—once considered an architectural marvel—was dismantled and sold at auction for scrap. By 1901 evidence of the Library of Congress in the Capitol had largely vanished. Only traces remained in the building’s fabric, including the library’s black and white marble flooring, which was reused in the corridor one floor below.10

The early history of the library serves as a reminder that, when walking the halls of the Capitol today, it is easy to forget such spaces—even those, like the library, that were once considered among the building’s architectural gems. Historical prints and photographs in the U.S. Senate Collection can help us to remember and revisit the Library of Congress and other sites in the Capitol that are no longer extant. Additional historical images of the Library of Congress, as well as depictions of other interior Capitol spaces, are available on the Senate website.

Notes

1. An Act to make further provision for the removal and accommodation of the Government of the United States, 2 Stat. 55 (April 24, 1800).

2. An Act concerning the Library for the use of both Houses of Congress, 2 Stat. 128 (January 26, 1802); Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, The Original Library of Congress: The History (1800–1814) of the Library of Congress in the U.S. Capitol, report prepared by Anne-Imelda Radice, 97th Cong., 1st sess., 1981, 2, 5–7. Latrobe quoted in U.S. House of Representatives, Documentary History of the Construction and Development of the United States Capitol Building and Grounds, 58th Cong., 2nd sess., H. Rpt. 646, 148.

3. William C. Allen, History of the United States Capitol: A Chronicle of Design, Construction, and Politics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 109; Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Original Library of Congress, 26; “Congressional Library Room,” Wilmingtonian and Delaware Register, January 6, 1825.

4. Allen, History of the United States Capitol, 147–48; Robert Mills, Guide to the Capitol of the United States, Embracing Every Information Useful to the Visiter [sic], Whether on Business or Pleasure (Washington, D.C., 1834), 47.

5. Allen, History of the United States Capitol, 157–59, 206; “The Fire at the Capitol,” Cleveland Daily Herald, December 24, 1851.

6. Allen, History of the United States Capitol, 207; “The Library of Congress,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 46, no. 271 (December 1872): 46; “Adornments of the National Capitol,” Sun [Baltimore, MD], August 24, 1853, 1.

7. “The Library of Congress,” 48; US Senate, Office of Senate Curator, Isaac Bassett Manuscript Collection, Box 8, Folder C, p. 125, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Isaac Bassett Manuscript Collection, Box 13, Folder C, p. 58a; An Act to provide for the Transfer of the Custody of the Library of the Smithsonian Institute to the Library of Congress, 14 Stat. 13 (April 5, 1866); An Act to revise, consolidate, and amend the Statues relating to Patents and Copyrights, 16 Stat. 198 (July 8, 1870).

8. “The Library of Congress,” 49.

9. John Y. Cole, “The Main Building of the Library of Congress: A Chronology, 1871–1965,” Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 29, no. 4 (October 1972): 267; An act authorizing the construction of a building for the accommodation of the Congressional Library, 24 Stat. 12 (April 15, 1886).

10. Joint Resolution Relating to the use of the rooms lately occupied by the Congressional Library in the Capitol, 31 Stat. 719 (June 6, 1900); Allen, History of the United States Capitol, 370.

|

| 202405 07“What Hath God Wrought”: Morse’s Telegraph in the Capitol

May 07, 2024

On May 24, 1844, Samuel F. B. Morse achieved a historic triumph when he successfully transmitted a message over copper wire from the Senate wing of the U.S. Capitol to Baltimore, Maryland, the first long-distance demonstration of his electromagnetic telegraph. His invention would revolutionize communications in the United States and throughout the world.

On May 24, 1844, Samuel F. B. Morse achieved a historic triumph when he successfully transmitted a message over copper wire from the Senate wing of the U.S. Capitol to Baltimore, Maryland, the first long-distance demonstration of his electromagnetic telegraph. His invention would revolutionize communications in the United States and throughout the world.

The son of famed preacher and geographer Jedidiah Morse—whose book The American Geography (1789) was a best-seller in the country for decades—Samuel Morse began his career as an artist. After graduating from Yale College in 1811, he went to London to study painting and returned to the United States in 1815 with hopes of earning public acclaim for his art. His first major painting, a now-famous depiction of the House of Representatives in session, was a commercial failure, leaving him to earn a meager living as a portrait painter. In 1824 he won the commission to paint a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette during his tour of America, and the painting launched him into the upper echelon of New York artists. In the 1830s, Morse went on to found and lead the National Academy of Design and became a professor at the University of the City of New-York (later known as New York University). He also became active in politics as chief spokesman for the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Native American Democratic Association. His career as a painter effectively ended in 1837, when he failed to win a commission for one of four monumental paintings to be added to the Capitol Rotunda, leaving him dejected and embarrassed.1

That same year, Morse’s interest in technology and invention set him on a new path. More than five years earlier, building on what others had learned in the fields of electricity and electromagnetism, Morse had conceived of transmitting messages using electrical current over wire and had built crude devices for sending and receiving these coded messages. In the fall of 1837, news about experiments in electrical telegraphs began to trickle into the United States from Europe. Upon learning this news, Morse quickly began to publicize his earlier work on the electric telegraph and identified himself as its inventor. Amid challenges to this claim from other inventors, and seeking to protect his rights in the invention, Morse reached out to his friend and Yale classmate Henry L. Ellsworth, who was Commissioner of Patents. Ellsworth provided him with a caveat, a document that preserved his claim of priority, while he prepared to apply for a patent.2

Not having expertise in the science of electricity, Morse partnered with a chemistry professor at the University of the City of New-York, Leonard Gale, to build a working telegraph, and in September 1837 the two men gave their first demonstration. Morse then turned to a former student and toolmaker, Alfred Vail, to assist with refining and producing his instruments. In December Morse submitted a proposal to Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury, who had been tasked by the House of Representatives with soliciting proposals for the construction of a telegraph system in the United States. All but one of the respondents presented plans for an optical telegraph—a series of towers with humans sending signals in semaphore to one another, a version of which had already been established in France. Morse was the lone respondent to propose an “electromagnetic telegraph,” with electrical signals sent over long distances by wire. Morse informed Woodbury that his device had sent a signal over 10 miles of spooled wire and that he “had no doubt of its effecting a similar result at any distance.”3

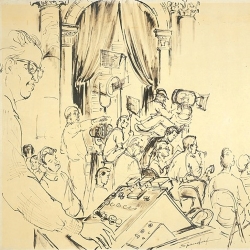

After demonstrations in New York and Philadelphia—in which Morse introduced the now famous code of dashes and dots that bears his name—he set up his equipment in the room of the House Committee on Commerce in the Capitol in February 1838 and gave a demonstration, explaining the technology to a group composed of members of Congress and President Martin Van Buren and his cabinet. In an era when investment funds were scarce and public support for national infrastructure was hotly debated, many inventors came to Congress looking for financial support. “It was not an uncommon thing for inventors of all kinds of outlandish and impractical machines to hang around the Capitol buttonholing every senator and member they could meet,” recalled Senate doorkeeper Isaac Bassett. The House Committee on Commerce, chaired by Francis O. J. Smith, asked Morse to submit a full report on his invention and, once received, recommended to the full House an appropriation of $30,000 to construct a 50-mile test line. Smith was so impressed by the potential of Morse’s telegraph that after losing his bid for reelection, he signed on as one of Morse’s partners.4

Unfortunately for Morse, the financial panic of 1837 had weakened political support for public investment in infrastructure projects, and over the next four years Congress took no action on the Commerce Committee’s bill. The news in 1842 that English telegraphers were seeking investors in the United States and that the Commerce Committee was considering funding a version of a French optical system (at a fraction of the cost of an electromagnetic system) set a fire under Morse, prompting him to finally take steps to acquire his U.S. patent and once again seek funding from Congress.5

Morse began a correspondence with Representative William Boardman of Connecticut to get a petition on the floor of the House urging the Commerce Committee to explore establishing an electromagnetic telegraph system. With improved equipment, Morse began a new round of public demonstrations in New York and succeeded in passing a signal over 33 miles of wire. With the support of Boardman and Representative Charles Ferris of New York, he was able to resume his demonstrations in the Capitol, running wire from the Commerce Committee room across the length of the building to the Senate Naval Affairs Committee room. Ferris then submitted to the full House on behalf of the Commerce Committee a report stating that Morse’s apparatus was “decidedly superior to any now in use” and drafted legislation to appropriate the $30,000 to support the construction of a telegraph line “of such length, and between such points, as shall fully test its practicability and utility.” It passed the House and Senate and was signed into law on the last day of the Congress on March 3, 1843.6

Morse and his partners regrouped in Washington to begin the work on the test line. They chose Baltimore as the destination, with plans to install the wire along the route of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, a process delayed by numerous setbacks and frigid temperatures. In April 1844, Morse again set up his equipment in the Capitol, this time in a room on the north end of the Senate wing. One person who saw Morse’s apparatus in the Capitol later characterized the Senate room as “small and dingy” with a window “looking out onto Pennsylvania Avenue,” though the exact location remains unclear. As the wire reached farther east, Morse began sending out test messages, and on May 1, he gave the American public a first taste of what the electric telegraph could do. The Whig Party was holding a convention in Baltimore to nominate its presidential ticket. Alfred Vail, who had set up a station in Annapolis, 22 miles from Washington, intercepted the news of the balloting being carried by rail. He immediately transmitted it to Morse at the Capitol, bringing news of Henry Clay’s nomination to Washington a full hour before the train carrying the same message arrived.7

Finally, on May 24, with the wire stretching 38 miles between Washington and the railroad depot in Baltimore, Morse was prepared to officially open the telegraph line. In front of a small group of guests, he invited Annie Ellsworth, the daughter of the patent commissioner, to compose the first message. She chose the biblical phrase, “What hath God wrought.” Moments later, an identical message was returned from Vail in Baltimore, making the experiment a stunning success. Decades later, accounts stated that this first message was sent from the Old Supreme Court Chamber, and in 1944, to commemorate the centenary of the event, a plaque was placed outside the chamber identifying it as the site of the demonstration. Researchers have found no documentation, however, to suggest that Morse moved from the room in the Senate wing where he had set up his equipment, making it the most likely location from which the famous message was sent.8

The May 24 demonstration was a private event and attracted little press attention. Days later, Morse demonstrated the revolution in communications to a wider audience. As the Democratic Convention met in Baltimore to select their presidential candidate, Vail telegraphed to the Capitol “with the rapidity of lightning” minute-by-minute updates on the balloting and the dramatic nomination of James K. Polk. President Pro Tempore Willie Mangum called the telegraph “a Miraculous triumph of Science” and recounted that a crowd of as many as a thousand eagerly awaited convention news outside of the Capitol. Morse wrote to his brother that the crowd “of some hundreds” called him to make an appearance at the window and offered three cheers to him and the telegraph. “Time and space have been completely annihilated,” declared one correspondent.9

Morse hoped to secure long-term federal funding to extend his line from Baltimore to New York and eventually to sell his invention to the government. Congress, however, appropriated only an additional $8,000 to keep the existing line in operation for another year under the direction of the Post Office, with Morse paid a salary as superintendent. Despite widespread awe at the technological achievement, lawmakers had trouble envisioning the telegraph as a useful, profitable venture. When renewal of the appropriation came up in 1845, Senator George McDuffie of South Carolina asked, “What is this telegraph to do? Would it transmit letters and newspapers?” Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri praised the technology and saw a future for it, but “wanted it to be called for by the commerce of the country, and pay its own expenses.” Congress funded the Washington-Baltimore line for only two more years, and in 1847 the Post Office leased it to private investors.10

Morse spent the next 20 years embroiled in legal fights as he, his partners and agents, and business rivals feuded over the rights and profits of establishing and growing a nationwide telegraph network. Despite Congress’s decision not to fund Morse’s work further and all the challenges that followed, private investment poured into the telegraph industry. Two decades after Morse’s Capitol demonstration, 100,000 miles of telegraph wire connected towns and cities across the United States, and Morse finally reaped the financial rewards of his invention. A few years later, the first transatlantic cable was laid between the United States and Europe. The telegraph revolutionized communications by sending news and information over vast distances almost instantaneously. It hastened westward expansion and spurred economic growth and investment in the United States, providing a handsome return on Congress’s initial investment.

Notes

1. Kenneth Silverman, Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F. B. Morse (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003), 3–20; “Samuel F. B. Morse,” National Gallery of Art, accessed April 11, 2024, https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1737.html.

2. Silverman, Lightning Man, 147–59.

3. Telegraphs for the United States, H. Doc. 15, 25th Cong., 2nd sess., December 11, 1837; Silverman, Lightning Man, 160–61.

4. Silverman, Lightning Man, 168–71; US Senate, Office of Senate Curator, Isaac Bassett Papers, Box 20, Folder B, p. 3, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Richard R. John, Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2010), 34–36.

5. Silverman, Lightning Man, 212–14.

6. An Act to test the practicability of establishing a system of electro-magnetic telegraphs by the United States, 5 Stat. 618 (March 3, 1843); Silverman, Lightning Man, 220–21.

7. John W. Kirk, “Historic Moments: The First News Message by Telegraph,” Scribner's Magazine 11 (May 1892): 652–56, https://todayinsci.com/Events/Telegram/TelegraphFirstNews.htm (accessed April 9, 2024).

8. Silverman, Lightning Man, 174–214, 220–21.

9. Willie Mangum to Priestly H. Mangum, May 29, 1844, in Henry T. Shanks, ed., Papers of Willie Person Mangum, Vol. IV, 1844–1846 (North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 1955), 127–28; Morse to Sidney Morse, May 31, 1844, Samuel Morse Papers, Bound volume---15 January–8 June, Library of Congress Manuscript Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mmorse.017001/?sp=276&st=image&r=-0.083,0.058,1.106,0.66,0 (accessed April 9, 2024); “The Magnetic Telegraph,” Baltimore Sun, May 31, 1844, 2.

10. Congressional Globe, 28th Cong., 2nd sess., February 28, 1845, 366; Silverman, Lightning Man, 257–58; John, Network Nation, 58–61.

|

| 202312 11In Form and Spirit: Creating the Statue of Freedom

December 11, 2023

The massive bronze Statue of Freedom has been perched atop the great dome of the United States Capitol since its assembly was completed on December 2, 1863, amidst the pall of civil war. As the crowning feature of the building’s new cast-iron dome, it offered a glimmer of hope that the nation would endure. The continuation of the construction of the dome had served as a symbolic backdrop during the dark war years, but Freedom’s journey to the top of the dome had begun years before.

The massive bronze Statue of Freedom has been perched atop the great dome of the United States Capitol since its assembly was completed on December 2, 1863, amidst the pall of civil war. As the crowning feature of the building’s new cast-iron dome, it offered a glimmer of hope that the nation would endure. The continuation of the construction of the dome had served as a symbolic backdrop during the dark war years, but Freedom’s journey to the top of the dome had begun years before.

The Capitol underwent a major transformation during the Civil War. On March 4, 1861, with war looming, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his first inaugural address in the shadow of the half-finished dome. The building was in the midst of a major expansion project that had begun 10 years earlier and included the construction of two large wings and a new, taller dome. At the onset of the war, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, the superintendent of the Capitol extension and dome construction, observed that the government had “no money to spend except in self defense” and issued the order to stop working. Despite this order, the iron foundry hired to construct the dome, Janes, Fowler and Kirtland, continued the project without pay. The foundry worried that the cast iron materials already procured would be damaged or destroyed if installation was delayed.1

Members of Congress, many of whom shared similar concerns, debated a resolution to restore funding in the spring of 1862. “Every consideration of economy, every consideration of protection to this building, every consideration of expediency requires that it should be completed, and that it should be done now,” Vermont senator Solomon Foot appealed to his fellow senators. “To let these works remain in their present condition is, in my judgment, to say the least of it, the most inexcusable, needless, and extravagant waste and destruction of property,” he argued. “We are strong enough yet, thank God, to put down this rebellion and to put up this our Capitol at the same time.” Congress restored construction funding in April 1862, and the foundry’s dome contract was renewed. Slowly and steadily, the massive dome became a reality during those difficult war years. The vision of this continuing endeavor provided inspiration during this perilous time. “If people see the Capitol going on, it is a sign we intend the Union shall go on,” remarked President Abraham Lincoln. “War or no war, the work goes steadily on,” reported the Chicago Tribune.2

To crown the new dome, Architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter, who designed the cast-iron structure, called for a large statue, which he originally conceived as an allegorical figure “holding a liberty cap”—a cloth cap worn by the formerly enslaved in Ancient Greece and Rome that later became a popular symbol of the American and French Revolutions. In 1855 Meigs asked American sculptor Thomas Crawford, who had produced other sculptural pieces for the Capitol project, to create a representation of Liberty for the dome’s statue. Working in his studio in Rome, Crawford instead proposed a figure representing “Freedom triumphant in War and Peace.” His first design, a female holding an olive branch in one hand and a sword in the other, was made before he realized that the sculpture needed more height and a taller pedestal. His second sketch, which Crawford said represented “Armed Liberty,” was a female figure in classical dress wearing a liberty cap adorned with stars and holding a shield and wreath in one hand and a sword in the other.3

Upon receiving Crawford’s second design, Meigs rightly anticipated that his superior, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, a Southern enslaver (and future president of the Confederacy) who oversaw the Capitol construction project, would object to the inclusion of the liberty cap. “Mr. Crawford has made a light and beautiful figure of Liberty…. It has upon it the inevitable liberty cap, to which Mr. Davis will, I do not doubt, object,” Meigs recorded in his journal. Indeed, Davis did object. “History renders [the liberty cap] inappropriate to a people who were born free and would not be enslaved,” Davis argued, willfully ignoring the millions of enslaved people who toiled across the nation. “[S]hould not armed Liberty wear a helmet?” Davis offered. Crawford’s third and final design reflected Davis’s suggestion. Freedom was clad with a helmet, "the crest of which is composed of an eagle’s head and a bold arrangement of feathers, suggested by the costume of our Indian tribes," Crawford explained.4

Once the statue design was approved, Crawford prepared a plaster model in his studio, his last work before he fell ill and died in 1857. Divided into five separate pieces, the model was shipped to America. After a long and arduous journey in a ship plagued by leaks, all of the pieces finally arrived in Washington in March 1859. An Italian craftsman working in the Capitol reassembled the model, covering all the seams with fresh plaster, and it was temporarily displayed in the old House Chamber (now known as Statuary Hall). Clark Mills, the owner of a local iron foundry, was hired to cast the statue in bronze in 1860. When the time came to disassemble the plaster model for casting, the Italian craftsman demanded additional pay from Mills, claiming that he alone knew how to separate the model. Mills turned instead to one of his foundry workers, an enslaved African American artisan named Philip Reid, who skillfully devised a method of separating the plaster model so that the individual sections could be cast and the bronze statue assembled. Reid labored seven days a week on Freedom, the only worker in Mills’s foundry paid to attend to the statue on Sundays, according to government records. Reid's rate of pay was $1.25 per day; however, as an enslaved man, he was likely only permitted to keep his Sunday earnings. While Reid was one of many enslaved people who helped to build the Capitol, he is unique in that his name has been documented in official records. “Philip Reid’s story is one of the great ironies in the Capitol’s history,” architectural historian of the Capitol William C. Allen observed, “a workman helping to cast a noble allegorical representation of American freedom when he himself was not free.”5

More ironic yet was the fact that when the statue was finally placed atop the dome on December 2, 1863, Reid was a free man, liberated by the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act in 1862 . Reporting from Washington that December day, a correspondent for the New York Tribune recounted Reid’s central role in the creation of Freedom, and reflected, “Was there a prophecy in that moment when the slave became the artist, and with rare poetic justice, reconstructed the beautiful symbol of freedom for America?” The installation of the Statue of Freedom proved to be symbolic, signifying the enduring nation in a time of civil war. A solemn ceremony marked completion of the dome and the placement of Freedom. The “flag of the nation was hoisted to the apex of the dome,” wrote an observer, “a signal that the ‘crowning’ had been successfully completed.” A salute was ordered to commemorate the event, “as an expression…of respect for the material symbol of the principle upon which our government is based.” The 12 forts that guarded the capital city answered with cannon fire when artillery fired a 35-gun-salute—one gun for each state, including those of the Confederacy.6

“Freedom now stands on the Dome of the Capitol of the United States,” wrote the Commissioner of Public Buildings, Benjamin Brown French, in his journal; “May she stand there forever, not only in form, but in spirit.” It was an appropriate finale to a year that began with Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. “Let us indulge the hope that our posterity to the end of time may look upon it with the same admiration which we do today,” one observer wrote of Freedom that December day, “and an unbroken Union three years since would have viewed this glorious symbol of patriotism and achievement of art.” Indeed, the nation emerged from the Civil War damaged but intact, improved by the permanent emancipation of four million African Americans in December 1865. 7

Notes

1. William C. Allen, The Dome of the United States Capitol: An Architectural History (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1992), 55.

2. Congressional Globe, 37th Cong., 2nd sess., March 25, 1862, 1349; Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, eds., Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 147; “The Capitol Improvements,” Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1863, 1.

3. “Statue of Freedom,” Architect of the Capitol, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/statue-freedom; "The Liberty Cap in the Art of the U.S. Capitol," Architect of the Capitol, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/blog/liberty-cap-art-us-capitol; William C. Allen, History of the United States Capitol: A Chronicle of Design, Construction, and Politics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 246; Allen, Dome, 42.

4. Wendy Wolff, ed., Capitol Builder: The Shorthand Journal of Montgomery C. Meigs, 1853–1859, 1861 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2001), 332; Allen, Dome, 42–43.

5. Allen, Dome, 42–43; John Philip Colletta, "Clark Mills and His Enslaved Assistant, Philip Reed: The Collaboration that Culminated in Freedom," Capitol Dome 57, (Spring/Summer 2020): 19; "History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the United States Capitol," report prepared by William C. Allen, Architectural Historian, Office of the Architect of the Capitol, June 1, 2005, p. 16, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office.

6. “The Statue of Freedom,” correspondence of the New York Tribune, reported in the Chicago Tribune, December 14, 1863, 1; "The Statue on the Capitol Dome," National Intelligencer, December 3, 1863, 3; S. D. Wyeth, The Rotunda and Dome of the US. Capitol (Washington, D.C.: Gibson Brothers, 1869), 193.

7. Benjamin Brown French, Witness to the Young Republic, A Yankee’s Journal, 1828–1870 (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1989), 439; "The Statue on the Capitol Dome," National Intelligencer, December 3, 1863, 3.

|

| 202310 10The First National Burial Ground: Congressional Cemetery

October 10, 2023

When Pierre L’Enfant produced his design for the new federal city in 1791, his plan did not include burial grounds. With the relocation of the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia set to happen by 1800, DC’s commissioners anticipated the influx of population that would follow and set aside land in 1798 for two cemeteries on the outskirts of the city, one on the west side and the other on the east. When the site on the east side of the city proved to be unsuitable for burials, a group of parishioners of Christ Church on Capitol Hill established a new burial ground two miles from the Capitol, known by the 1830s as Congressional Cemetery.

When Pierre L’Enfant produced his design for the new federal city in 1791, his plan did not include burial grounds. With the relocation of the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia set to happen by 1800, DC’s commissioners anticipated the influx of population that would follow and set aside land in 1798 for two cemeteries on the outskirts of the city, one on the west side and the other on the east. When the site on the east side of the city proved to be unsuitable for burials, a group of parishioners of Christ Church on Capitol Hill established a new burial ground along the Anacostia River, two miles from the Capitol. In time this cemetery came to be regarded as the first national burial ground, known by the 1830s as Congressional Cemetery.1