Adjusting to new technology is never easy. With today’s proliferation of smart phones, smart watches, and virtual reality devices, it might be hard to appreciate that a hundred years ago the rotary dial telephone was cutting-edge technology. And some senators did not like it!

A telephone was first installed in the U.S. Capitol in 1880, four years after its demonstration by inventor Alexander Graham Bell. Situated in a room near the House Chamber, the telephone was placed under the supervision of the House doorkeeper. On the Senate side of the Capitol, telephones for the offices of the Secretary of the Senate, the Senate Sergeant at Arms, and the Senate Post Office followed in the 1880s. In 1897 the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company, which provided phone service to the District of Columbia, installed a switchboard with capacity for 100 lines in the Senate Reception Room with 25 to 30 active lines in service. When users of one of these original phones picked up the receiver, they were connected to a switchboard operator who would patch the call through to an office in the Capitol or to an outside line to reach someone off of Capitol Hill.1

The Senate and House switchboards were replaced in 1901 by a single switchboard that served the entire Capitol. Three operators directed calls on the new switchboard, which was installed in the Capitol’s first floor. As the telephone grew in popularity, Congress installed larger switchboards and hired more operators to connect calls, placing them under the supervision of operator Harriott G. Daley. By 1926, with every office in the Capitol as well as the House and Senate office buildings equipped with a phone, the Capitol switchboard, by then located in the House office building, served almost 1,700 lines, the equivalent of a switchboard serving a small city. Daley supervised 18 operators—almost exclusively women—who handled between 300 and 400 calls per hour.2

In 1930 a new advancement in telephone technology arrived at the Capitol: the dial telephone. Rather than placing a call with an operator, members of Congress would now use the rotary dial to place the call directly, triggering an automatic switchboard to connect to the receiving party. Although the first rotary dial phones and automatic switchboards dated back to the 1890s, they suffered from a number of technical and financial drawbacks and were not widely adopted. More importantly, executives of the Bell Telephone Company—which held a virtual monopoly over the nation’s telephone system—believed that dial phones and automatic switching could not compete with switchboard operators in providing personalized service and individual attention to customers. Companies in the Bell System—controlled after 1900 by American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T)—did not adopt dial phones until 1919, when the company sought cost savings by replacing operators with automatic switchboards. Even then, phone companies prudently introduced the new system gradually, recognizing, as one executive wrote, that “subscribers are prejudiced in favor of the system they have used for forty years, and will not, I am afraid, in their present frame of mind accept the dial.” AT&T thus embarked on a campaign to educate the public on how to use the new phones and the benefits of automatic switching.3

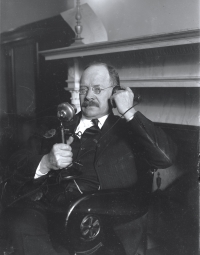

One phone user who did not “accept the dial” was Senator Carter Glass of Virginia. When the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company, by then a subsidiary of AT&T, installed dial telephones on the Senate side of the Capitol in May 1930, the 72-year-old veteran lawmaker introduced a resolution:

Whereas dial telephones are more difficult to operate than are manual telephones; and Whereas Senators are required, since the installation of dial phones in the Capitol, to perform the duties of telephone operators in order to enjoy the benefits of telephone service; and Whereas dial telephones have failed to expedite telephone service; Therefore be it resolved that the Sergeant at Arms of the Senate is authorized and directed to order the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Co. to replace with manual phones within 30 days after the adoption of this resolution, all dial telephones in the Senate wing of the United States Capitol and in the Senate office building.

Glass was not alone in his objections to the dial phone. He received correspondence from individuals around the country lauding his resolution and complaining about the decline of personal service that accompanied automatic switching. President Herbert Hoover had banned dial phones from the White House when he took office in 1929, and North Carolina representative Charles L. Abernathy introduced a similar resolution in the House of Representatives.4

Glass’s resolution received broad support in the Senate. Arizona's Henry Ashurst objected to dial telephones and praised Glass for his restrained language in introducing his resolution. The Congressional Record would not be mailable, he said, "if it contained in print what Senators think of the dial telephone system.” (Apparently, Glass’s language was still a little too salty for the Record. A newspaper reported that he exclaimed, “I want those abominable dial telephones taken out,” but that statement did not make it into the Record.) When Joe Robinson of Arkansas pointed out that the dial telephones were “a great conservation measure” in that they would allow for reduction in the number of telephone employees, Glass shot back, “I object to that phase of it, and I object to being transformed into one of the employees of the telephone company without compensation.” When Washington senator Clarence Dill asked why the resolution did not also ban the dial system from the entire District of Columbia, Glass said he hoped the phone company would take the hint and do so. The resolution passed without objection.5

The dial telephone, of course, had its defenders, particularly the national telephone companies working under the umbrella of AT&T. The New York Telephone Company, which began switching to dial phones in 1922, put out a statement a few days after Glass introduced his resolution noting they had received very few complaints about the new phones and that the company could not maintain efficient service for its growing number of customers without the dial phone and automatic switching. The company pointed out that the phones were particularly helpful for immigrants who weren’t fluent in English, as they had a difficult time communicating with operators. “The dial represents the highest type of telephone in existence,” the company concluded.6

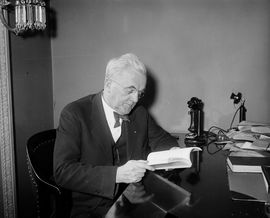

Despite Glass and his many allies, some members of the Senate embraced the new technology. Senator George Norris of Nebraska declared, “I like the dials.” He believed that passing the ban meant the Senate was “standing in the road of human progress.” One day before the scheduled removal of all dial phones, Maryland senator Millard Tydings offered a resolution to give senators a choice as to which phone was installed in their offices. Glass objected. He thought it onerous for senators to have to contact the phone company to convey their preference. Beginning the next day, the phone company removed 789 dial phones from the Senate.7

A week later, senators reached a compromise. Senator Claude Swanson of Virginia introduced a resolution to instruct the phone company to install phones that could be operated either by operator or by dial. In acquiescing to the deal, Glass insisted that he had not objected to senators having access to dial telephones, but rather that the changeover appeared to be “purely for the benefit of the telephone company.” Senator Dill, who had complained that the dial phone “could not be more awkward,” added that in opposing the phones he was not against “progress,” as some had charged. “So long as I am not pestered with the dial and may have the manual telephone, while those who want to be pestered with it . . . may have it, all right.”8

The final compromise meant that the Senate’s manual switchboards and operators would remain in place. Harriott Daley managed them until her retirement in 1945. Phone and switching technology continued to advance greatly in the Senate of the 20th and 21st centuries, but today, Capitol operators still play an important role in Senate telecommunications.

Notes

3. Kenneth Lipartito, “When Women Were Switches: Technology, Work, and Gender in the Telephone Industry, 1890–1920,” American Historical Review 99, no. 4 (October 1994), 1075–1111; Venus Green, “Goodbye Central: Automation and the Decline of Personal Service in the Bell System, 1878–1921,” Technology and Culture 36, no. 4 (October 1995), 912–94; B. E. Sunny to H. B. Thayer, AT&T Vice President, March 18, 1919, AT&T Archives, quoted in Green, “Goodbye Central,” 944.

7. Congressional Record, 71st Cong., 2nd sess., June 19, 1930, 11,161; “Dial Phone Has Senate Friends, But Ban Stands,” Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1920, 3; “Senate’s Dial Phone War Simmering Down Quietly,” Washington Post, June 20, 1930, 1; “Choose Your Telephones,” Baltimore Sun, July 14, 1930, 6; S. Res. 278, 71st Cong., 2nd sess., June 20, 1930.