Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the selection of historic records featured in this month’s “Senate Stories,” which highlight the complex relationship between the Senate and the president.

Among the foundational principles of the U.S. Constitution is the separation of powers. In establishing three distinct branches of government—legislative, executive, and judicial—the Constitution divides authority to create the law, implement and enforce the law, and interpret the law. At the same time, many powers exercised by one branch may be shared with another. This system of checks and balances invites both compromise and conflict among the branches, especially between the legislative and executive, and prevents the consolidation of power in any single branch. For example, the Senate’s “advice and consent” is required for executive functions such as nominations and treaties. Conversely, the president has the power to veto legislation; however, Congress may overturn the veto with a two-thirds majority of those present and voting in both houses.1

The constitutional structure that provides for checks and balances is expansive and complex by design, generating an interdependence between the Senate and the executive branch that, combined with transient political interests, has historically demonstrated moments of high conflict as well as examples of great cooperation. This collection of historic documents from the Senate’s archives highlights the collaborations and the struggles that have defined the relationship between the Senate and the president. Each document, while capturing a specific moment in time with unique political conditions at play, also provides a broader view of the constitutional system of government in action, specifically the foundational principle of separation of powers and the complex system of checks and balances.

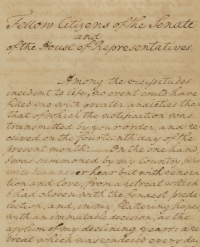

George Washington's First Inaugural Address, 1789

When George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the United States on April 30, 1789, he delivered this address to a joint session of Congress, assembled in the Senate Chamber in New York City’s Federal Hall. While this first occasion was not the public event we have come to expect, Washington's speech nevertheless established the enduring tradition of presidential inaugural addresses. Early presidential messages, including inaugural addresses and annual messages (now known as State of the Union addresses), are included in Senate records at the National Archives.

Although noting his constitutional directive as president "to recommend to your consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient," Washington refrained from detailing his policy preferences regarding legislation. Rather, on the occasion of his inaugural, he stated his confidence in the abilities of the legislators, insisting, "It will be…far more congenial with the feelings which actuate me, to substitute, in place of a recommendation of particular measures, the tribute that is due to the talents, the rectitude, and the patriotism which adorn the characters selected to devise and adopt them."

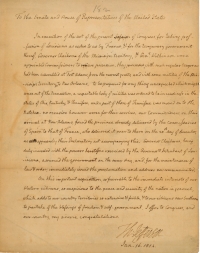

Message from President Thomas Jefferson to Congress Regarding the Louisiana Purchase, 1804

Treaty powers are among those shared by the president and the Senate. The Constitution provides that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur" (Article II, section 2). In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson's administration negotiated a treaty with France by which the United States purchased the vast Louisiana Territory. Questions arose concerning the constitutionality of the purchase, but Jefferson and his supporters successfully justified the legality of the acquisition. On October 20, 1803, the Senate approved the treaty for ratification by a vote of 24 to 7. The territory, which encompassed more than 800,000 square miles of land, now makes up 15 states stretching from Louisiana to Montana. In this congratulatory message to Congress dated January 16, 1804, President Jefferson reported on the formal transfer of the land to the United States and referenced the December 20, 1803, proclamation announcing to the residents of the territory the transfer of national authority.

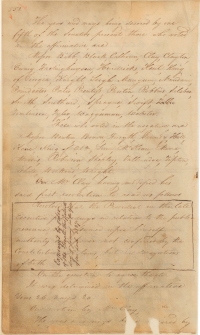

Page from the Senate Journal Showing the Expungement of a Resolution to Censure President Andrew Jackson, 1834

The March 28, 1834, censure of President Andrew Jackson represents a notably contentious episode in the executive-legislative relationship. For two years, Democratic president Andrew Jackson had clashed with Senator Henry Clay and his allies over the congressionally chartered Bank of the United States. The dispute came to a head when President Jackson, who had opposed the creation of the Bank, ordered the removal of federal deposits from the Bank to be distributed to several state banks. When his first Treasury secretary refused to do so, Jackson fired him during a Senate recess and appointed a new Treasury secretary, who carried out his orders. Senator Clay and his allies, who supported the Bank, believed that President Jackson did not have the constitutional authority to take such action, and they found the explanation given for moving the federal deposits “unsatisfactory and insufficient.” Clay introduced the resolution to censure the president, charging that Jackson had “assumed the exercise of a power over the Treasury of the United States not granted him by the Constitution and laws.” After extensive debate, the censure resolution passed. Jackson responded by submitting to the Senate a 100-page message arguing that the Senate did not have the authority to censure the president. The Senate again rebuffed the president by refusing to print the lengthy message in its Journal.2

Over the next three years, Missouri Democrat and Jackson ally Thomas Hart Benton campaigned to expunge the censure resolution from the Senate Journal. In January 1837, after Democrats regained the majority in the Senate, Senator Benton succeeded. On January 16, the secretary of the Senate carried the 1834 Journal into the Senate Chamber, drew careful lines around the text of the censure resolution, and wrote, “Expunged by order of the Senate."

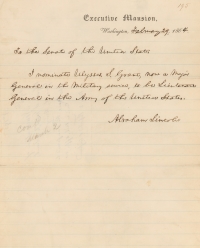

President Abraham Lincoln's Nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to be Lieutenant General of the U.S. Army, 1864

Like treaty powers, the Constitution requires that the Senate serve as a check on the president's nomination authority. The president nominates federal judges, members of the cabinet, and military officials, among others, whose nominations are confirmed with the advice and consent of the Senate. This remarkable document dated February 29, 1864, representing a critical moment in the Civil War, is President Abraham Lincoln's nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to be lieutenant general of the U.S. Army, at the time the United States’ highest military rank. Previously, only two men had achieved that rank—George Washington and Winfield Scott—and Scott’s had been a brevet promotion. To facilitate Grant’s nomination and ensure his superior status among military officers, Congress passed a bill to revive the grade of lieutenant general and authorize the president "to appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, a lieutenant-general, to be selected among those officers in the military service of the United States . . . most distinguished for courage, skill, and ability." The Senate confirmed Lincoln's nomination of Grant on March 2, 1864.

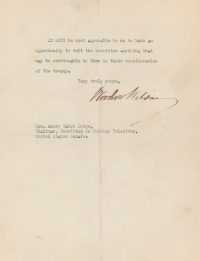

Letter from President Woodrow Wilson to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, 1919

A unique event in legislative-executive relations occurred on August 19, 1919, when President Woodrow Wilson offered testimony before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations on the Treaty of Versailles, then under consideration by the committee. The meeting, convened in the East Room of the White House, stood “in contradiction of the precedents of more than a century,” the Atlanta Constitution reported, noting the rarity of a president offering testimony before a congressional committee.3

The Treaty of Versailles ended military actions against Germany in World War I and created the League of Nations, an international organization designed to prevent another world war. President Wilson had led the U.S. delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and had been a principal architect of the treaty. For months, Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Henry Cabot Lodge had encouraged the president to seek the advice of the Senate while negotiating the treaty’s terms, but Wilson chose to negotiate on his own. Personally invested in the treaty’s adoption, the president hand-delivered it to the Senate on July 10, 1919, and urged its approval for ratification in an unusual speech before the full Senate.

Under Senate rules, the treaty went to the Foreign Relations Committee for consideration, which held public hearings from July 31 to September 12, 1919. Among the most vocal critics of the proposed treaty was Lodge, who was also the Senate majority leader. Lodge opposed several elements of the treaty, particularly those related to U.S. participation in the League of Nations. On behalf of the Foreign Relations Committee, Lodge asked Wilson to meet with the committee to answer senators’ questions. With this letter, President Wilson agreed to Lodge's request and proposed the August 19 date at the White House.

Ultimately, Lodge’s committee insisted on a number of “reservations” to the treaty, but Wilson and Senate proponents of the treaty were unwilling to compromise on terms. Consequently, on November 19, 1919, for the first time in its history, the Senate rejected a peace treaty.

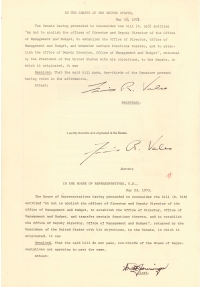

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, 1973

Under the Constitution, the president is permitted to veto legislative acts, but Congress has the authority to override presidential vetoes by two-thirds majorities of both houses. This document provides a comprehensive example of these constitutional checks and balances in action. In 1973 Congress passed S.518, which sought to abolish the offices of the director and deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget and reestablish those positions with a new requirement that they be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. The bill’s proponents argued that because these positions had evolved to wield significant power, they ought to be subject to Senate confirmation.

President Richard Nixon vetoed the bill on May 18, claiming it to be unconstitutional. “This step would be a grave violation of the fundamental doctrine of separation of powers,” Nixon stated. While the Senate achieved the necessary two-thirds majority to override the veto, the House did not, and Nixon’s veto was sustained. Congressional efforts to override Nixon’s veto were recorded by the secretary of the Senate and clerk of the House of Representatives on the reverse side of the bill.

The system of checks and balances set forth by the Constitution is a complex one, creating a legislative-executive relationship that is sometimes adversarial and at other times cooperative, but always interdependent. Illustrating the Senate's broad-ranging responsibilities and the integral role the Senate has played in this constitutional system, these treasured documents from the Senate’s archives help us to gain a better understanding of the conflicts and compromises that have historically defined the relationship between the Senate and the president.

Notes