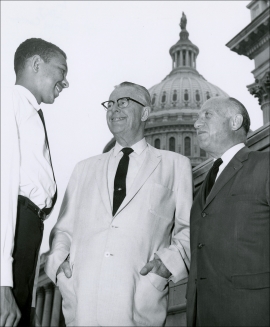

In April 1965, Senator Jacob Javits of New York appointed Lawrence Bradford, Jr., to be a Senate page. In celebrating the appointment, Javits and journalists identified Bradford as the first African American to serve in the Senate’s historic page program. Bradford’s appointment was a milestone, but there’s one problem with this celebration—while Bradford was certainly a trailblazer in his time, he was not, in fact, the first African American page. That distinction belongs to Andrew Foote Slade, a young man who served as a page between 1869 and 1881. Slade’s story, forgotten in the Senate by the 1960s, offers a window not just into the Senate of the late 19th century, but into the history of Washington, D.C.’s, free Black community.1

Andrew Slade was born in 1857, the son of Josephine Parke and William Slade, a prominent free Black couple from the District of Columbia. Josephine, born as a free woman in 1818, was the daughter of a woman who had been enslaved by George Washington’s step-grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, on his Arlington, Virginia, estate. William was born free in 1814; his mother was formerly enslaved by the Foote family of Virginia. Henry Foote later represented Mississippi in the Senate. William believed, in fact, that his mother was Senator Foote’s half-sister.2

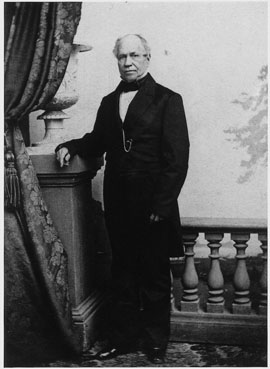

During the 1850s Andrew's father William was a porter at Brown’s Indian Queen Hotel, a posh establishment popular with Washington’s political elite. There he made connections that eventually took him to the White House. With a recommendation from Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, William first took a job at the Treasury Department as a messenger in 1861. In 1862 he was appointed to Abraham Lincoln’s White House, where free people of color were integral to its daily operations.3 William’s title was “usher,” one of the highest posts in the Executive Mansion staff. Andrew's mother, Josephine, also periodically worked at the White House as a seamstress, alongside African American dressmaker Elizabeth Keckly. The couple’s children, including Andrew, often played with young Tad Lincoln, even hosting him at their home, the boardinghouse they owned and operated on Massachusetts Avenue.4

In the White House, William Slade was not just a servant but a confidante of the president, someone Lincoln turned to as he considered the weighty questions of emancipation and the fate of freed African Americans. The Slades were leading figures in the District’s free Black community. William was an elder of the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church. As freed African Americans flooded into the capital during the war, the Slades, along with friend and colleague Elizabeth Keckly, created the Contraband Relief Association to provide assistance and organized a school at the First Colored Baptist Church. William served as president of the Social, Civil, and Statistical Association, an organization dedicated to achieving Black citizenship following the war. Josephine was a leading organizer in the movement for universal suffrage.5

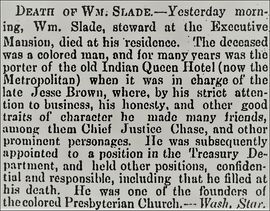

After the death of President Lincoln, William Slade continued to work at the White House under President Andrew Johnson, who appointed him steward in 1865. William died three years later at age 53. President Johnson paid his respects at the Slade home, and the funeral was officiated by Howard University president and former Senate chaplain Byron Sunderland, an abolitionist preacher. With William gone, Josephine Slade became the head of a household that included a son and daughter in their 20s and three younger children, including 11-year-old Andrew.6

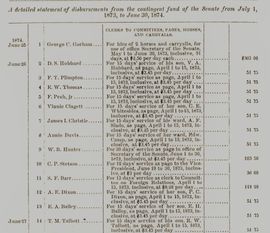

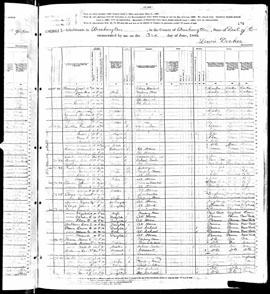

Andrew Slade was appointed as a Senate page in December 1869. He had been educated in a school in the District of Columbia for Black children established by African American civil rights activist John F. Cook, Jr. Andrew owed his appointment to Sergeant at Arms John R. French, an opponent of slavery and supporter of Black rights who had been friends with his father William. The Baltimore Sun noted the appointment and described Andrew as “a bright mulatto boy, son of . . . the late colored steward of the White House.” The writer speculated that the boy would be assigned as a special page to Senator Charles Sumner, another defender of Black civil rights who had been acquainted with his father. Although Andrew had not yet worked in the Chamber, the article stated that he was “on duty in the corridors.” Another reporter commented on Andrew’s light complexion and suggested that “such is the prejudice against a color, even milk-and-molasses color, that it has been thought best to introduce him by degrees into the Senate Chamber, lest the Caucasian pages leave en masse.” As was the case with other pages, Andrew’s salary, $3 per day, was paid to his mother.7

Historians have long known that many page appointments were given to local orphans or children of widowed mothers. While this appeared to be a way for the Senate to provide benefits to families in need, Josephine was anything but destitute. William left her a sizeable estate of $100,000, including $14,000 in real estate. But Josephine was a widow, nevertheless.8

Andrew’s first stint as a page was a short one. In 1870 his sister Marie Louise, a copyist at the U.S. Pension Office, married a prominent Black Arkansas politician named James W. Mason. Andrew, his mother, and his siblings all moved with Marie and her new husband to Arkansas later that year. In 1872, Josephine Slade passed away, leaving Andrew an orphan. The next year, he enrolled at Oberlin College’s preparatory school in Ohio and attended for one year.9

Andrew returned to Washington in January 1874, now 16 years old, and was again appointed as a page. Senate records list him as the ward of longtime assistant doorkeeper James I. Christie. Later that year, his sister returned to Washington following the death of her husband and Andrew spent the rest of the decade living with her while working as a page. He served as a riding page delivering messages throughout the District and eventually became a mail carrier for the Senate Post Office. He also likely worked on the Chamber floor and was reportedly a favorite of Vice President Henry Wilson. Andrew, in fact, helped attend to Wilson as he lay dying in his office across the corridor from the Chamber in 1875. 10

The Senate had no maximum age for pages in the late 19th century, so Andrew continued as a page into November 1881, when he was 24 years old. In December he applied for a position at the Pension Commission, supported by a recommendation from Democratic senator George Pendleton of Ohio, famous for his 1883 Civil Service Reform Act. In 1882, while visiting or living in Warwick, New York, Andrew submitted an application for a position at the Department of the Interior, with recommendations from Garland, Senator Henry Teller of Colorado—who had recently left the Senate to serve as secretary of the department—and T. W. Ferry of the Senate Post Office.11

It is unknown whether Andrew gained another government position, but by 1886 he was living in Philadelphia and working at the Tribune newspaper, the city’s recently founded African American paper. A reporter from the Washington Bee, another African American paper, noted meeting Andrew on a visit to the Tribune’s offices and described him as a man with “a good heart and a mild disposition” who was “well known in Washington.” The historical record offers little information about how Andrew fared in Philadelphia. In 1899 he is listed in the city directory as a driver. He died that year, at the age of 42, leaving behind a wife, Laura.12

Andrew Slade’s story, incomplete though it may be, offers a glimpse into an era of dramatic social changes in and around the Capitol and the role played by this prominent Black family. Andrew's mother and father both walked the corridors of official Washington and used what power they had to fight for the rights of African Americans in an era when those rights were under constant siege. Their stature likely opened the doors of the Senate to their son at a time when others like him would have been denied the opportunity.

We are left wondering, however, what Andrew thought about his position in the Senate and how he was received by senators of the 1870s. What role did Andrew’s race play in his experiences in and around the Senate Chamber? How did senators view Andrew, especially those former Confederates who returned to Congress in the years after Reconstruction, dedicated to maintaining the racial caste system in their home states? Perhaps Andrew Slade’s very presence served as a reminder to senators of the insecure future of Black Americans outside the Capitol. All of these questions and more will fuel future research by Senate historians.

Notes

2. Blake Wintory, “Biography of Josephine Lewis (Parke) Slade, 1818–1872,” Alexander Street, Biographical Database of Black Women Suffragists, accessed July 20, 2021, https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C5075826?account_id=45340&usage_group_id=45068. The District of Columbia was a popular destination for formerly enslaved African Americans manumitted from the upper South, leading to a free population of over 11,000 by 1860, about 20 percent of the city’s population. Dorothy Provine, “The Economic Position of the Free Blacks in the District of Columbia, 1800–1860,” Journal of Negro History 58, no. 1 (January 1973): 61.

3. John E. Washington, They Knew Lincoln (Oxford University Press, 2018; originally published 1942); James B. Conroy, “Slavery’s Mark on Lincoln’s White House,” White House Historical Association, accessed July 20, 2021, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/slaverys-mark-on-lincolns-white-house.

4. Wintory, “Biography of Marie Louise (Slade) Mason, 1844–1919,” Biographical Database of Black Women Suffragists, Alexander Street, accessed July 20, 2021, https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C4744667?account_id=45340&usage_group_id=45068; Conroy, “Slavery’s Mark on Lincoln’s White House.”

5. Natalie Sweet, “A Representative ‘of Our People’: The Agency of William Slade, Leader in the African American Community and Usher to Abraham Lincoln,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 34, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 21–41, accessed July 20, 2021, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0034.204; Diaries of Julia Wilbur, 1860–66, April 20, 1865, Haverford College, Quaker and Special Collections, Transcriptions by volunteers at Alexandria Archaeology, accessed July 20, 2021, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/JuliaWilburDiary1860to1866.pdf. For more on Black organizations in the District of Columbia during the Civil War, see Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C., (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

7. Receipts and Expenditures of Senate, 1870, S. Mis. Doc. 41-8, 41st Cong., 3rd sess., December 5, 1870, 2; Progressive American (NY), undated, in Isaac Bassett Papers, Box 34, Folder E, p. 130, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. [online version available through Archives Research Catalog (ARC Identifier 5423162, p. 2) at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5423162]; “Colored Page in the Senate,” Baltimore Sun, December 16, 1869, 1; “The Alta on Our Colored Brother,” San Jose Mercury News, December 28, 1869, 3; Assistant Doorkeeper Isaac Bassett noted in his unpublished memoir Andrew’s appointment as the “first colored page,” Isaac Bassett Papers, Box 3, Folder A, p. 31 [(ARC Identifier 5423058, p. 36) https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5423058].

9. “Colored Female Clerks,” Washington Evening Star, March 27, 1869, 1; Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Oberlin College for the College Year 1873–74, (Cleveland, OH: Press of Fairbanks, Benedict, & Co., 1873), 29; Wintory, “Marie Louise (Slade) Mason,” Biographical Database of Black Women Suffragists.

10. Receipts and Expenditures of Senate, 1874, S. Mis. Doc. 43-74, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., December 7, 1874, 10. Senator George Pendleton’s recommendation letter for Slade in 1881 indicated that he worked in the Senate Chamber. See Slade, Andrew F., File 2942, Appointments Division, Applications and Appointments 1881, Box no. 65, Department of the Interior, Record Group 48, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD; Progressive American (NY), undated, in Isaac Bassett Papers.

11. Slade, Andrew F., File 2942, Appointments Division, Applications and Appointments 1881, Box no. 65, Department of the Interior, Record Group 48, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD; Slade, Andrew F., Appointments Division, File 874, Applications and Appointments 1882, Box no. 72, Entry 27, Department of the Interior, Record Group 48, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD. Special thanks to Blake Wintory for sharing his research.

12. “Our Visit to Philadelphia,” Washington Bee, November 13, 1886; "Andrew Slade," Washington Bee, August 26, 1899. We know much more about Slade’s sister Marie Louise, who moved to Montana in 1889 and became a leader in the movement for women’s suffrage. She later moved to Paris and then London with her daughter, who studied to be an artist. See Wintory, “Marie Louise (Slade) Mason,” Biographical Database of Black Women Suffragists. Slade’s sister Katherine Slade went on to become a teacher and was a key source for John Washington’s They Knew Lincoln.