| 202508 29Fifty Years of Preserving and Promoting Senate History

August 29, 2025

In May 1974, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and political historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., wrote a letter to Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield supporting a proposal to establish a Senate Historical Office. “The creation of such an Office would be of benefit,” Schlesinger wrote, “not only to historians and concerned citizens but to the Senate itself.” The next year, with the bipartisan blessing of Mansfield and Republican leader Hugh Scott, the Senate Historical Office was established on September 1, 1975.

In May 1974, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and political historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., wrote a letter to Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield supporting a proposal to establish a Senate Historical Office. “The creation of such an Office would be of benefit,” Schlesinger wrote, “not only to historians and concerned citizens but to the Senate itself.” Schlesinger understood that the twin political crises of the 1970s—the Watergate scandal and the unpopular Vietnam War—had caused a growing number of Americans to lose faith in their institutions and to demand greater transparency from them. “If we are going to persuade the nation that Congress plays a role in the formation of national policy,” he wrote, “Congress will have to cooperate by providing the evidence for its contributions.” The next year, with the bipartisan blessing of Mansfield and Republican leader Hugh Scott, the Senate Historical Office was established on September 1, 1975.1

Tasked with overseeing the new office, Secretary of the Senate Francis Valeo articulated its mission. “Executive Branch departments and agencies have long had large historical offices and have long published or made public many of their important confidential papers,” Valeo explained in a letter to Senate appropriators justifying the creation of the new office. A Senate historical office would assist in the “organization of the Senate’s historic documentation,” serve as a “clearing house for public requests concerning historical subjects,” and “collect and preserve photographs depicting the history of the Senate.”2

Valeo hired Richard Baker to lead the new office. Baker brought a unique blend of skills and experience to the role. With degrees in history and library science, Baker had served as the Senate’s acting curator from 1969 to 1970 and then as vice president and director of research for the National Journal’s parent company. Former Washington Times staff photographer Arthur Scott filled the position of photo historian. Baker soon hired Leslie Prosterman as a research assistant and Donald Ritchie as a second historian.

Historians and newspapers heralded the office’s creation. “On behalf of the [American Historical] Association I want you to know how pleased we are that the Senate has established this new historical office,” wrote Mack Thompson, the organization’s executive director. “Much of the Senate’s business in the past was conducted in closed committee meetings,” noted Roll Call, leaving Senate records “locked away and forgotten,” resulting in the “history of significant public policy issues [being] written from the perspective of the Executive Branch where confidential records are generally declassified and published on a systematic basis.” The New York Times predicted that there would be much interest in the Senate’s “closed-door briefings on Pearl Harbor, the Cuban missile crisis, and the missile-gap controversy of the Eisenhower administration.” Generations of reporters, historians, and political scientists would come to rely upon the non-partisan expertise provided by Senate historians.3

One of the office’s most pressing early tasks was locating and arranging for the proper preservation of the Senate’s “forgotten” records. “Most senators in 1975 had given little thought to their papers,” recalled Baker in an oral history interview in 2010. Baker’s job was to persuade senators that selecting a repository for their papers was “prudent management practice … in the interest of public access.” There was much work to be done. Baker found humid attic and dank basement storerooms in the Russell Senate Office Building filled to overflowing with committee and member papers. A recent basement flood had destroyed 30 years of irreplaceable materials. Similarly, attic spaces, where temperatures soared in the summer and the prospect of a fire was not unthinkable, were ill-suited for safely preserving records. Racing the clock, Senate historians appraised collections and helped arrange for their long-term preservation. “Our major role is advisory,” Baker wrote during those early years. “We do not intend to build our own archives … [but to facilitate] the flow of archival materials to repositories where they will receive sufficient care and exposure.”4

The tidal wave election of November 1980 brought renewed urgency to Senate historians’ work. Eighteen departing senators had only a few months to vacate their offices. Some were leaving voluntarily, while others had been unexpectedly retired by their constituents. Historical Office staff scrambled to assist departing members—including Warren Magnuson of Washington State and Jacob Javits of New York, whose combined congressional service totaled 78 years—with moving their voluminous record collections to hastily designated repositories. Soon after that election, Baker hired Karen Paul as the Senate’s first archivist. Paul would devote the next 43 years of her career to advising senators, staff, and officers on the preservation and disposition of their records, developing archival policies and practices to ensure the preservation of Senate records for future generations, and building a community of professional Senate archivists.

Over the past five decades, the Senate Historical Office has built partnerships and institutional capacities to aid in the preservation of congressional records for the long term. Working with congressional leadership, the Historical Office helped to establish a separate division within the National Archives to serve as the official repository for congressional committee records in 1985—named the Center for Legislative Archives in 1988. In 1990 the Office co-founded the Advisory Committee on the Records of Congress to explore issues pertinent to congressional records management, and it co-created the Association of Centers for the Study of Congress in 2004, a nationwide consortium of congressional records repositories and research institutes. Today, Senate archivists continue to advance the Senate’s historical record by shaping how its documentation is preserved and accessed. They have developed and updated official records management policies and have pioneered digital preservation practices, creating workflows for archiving email, social media, and audiovisual records in line with national standards. Senate archivists also provide specialized staff training that equips members and support offices, as well as committees, to manage both paper and electronic records with confidence. The Historical Office also administers the Secretary of the Senate’s Preservation Partnership Grants that strengthen the capacity of repositories across the country to process and provide access to senators’ papers, broadening the range of materials available for research. This work safeguards the very documentation on which Senate history rests.

While preserved official records illuminate aspects of Senate history, they rarely tell the full story of an institution’s evolution. From the Historical Office’s earliest days, Senate historians have sought to document the social, cultural, and technological changes within the Senate with the Senate Oral History Project. Don Ritchie developed and led the project, with a mission to record and preserve the experiences of a diverse group of personalities—both staff and senators—who witnessed events firsthand and offer a unique perspective on Senate history. Interviews help to explain, for example, women’s evolving role in the Senate, and the impact of changing technology on the institution. There were no women senators serving in 1975, while 26 women serve in the 119th Congress. Only one senator’s office used a computer in 1975 to manage constituent services, while today, emails, the internet, and social media are ubiquitous Senate-wide. Collectively, these oral histories help to promote a fuller and richer understanding of the institution’s evolution and of its role in governing the nation.

The advent of the internet in the mid-1990s provided new opportunities to share Senate history with a broader range of audiences. When Betty Koed joined the team as assistant historian in 1998, she began populating the (then relatively) new Senate website with oral history transcripts and historical information. Today, the Historical Office has integrated a wealth of Senate history across Senate.gov, created a Senate Stories blog, and developed online exhibits including “The Civil War: The Senate’s Story,” “The Civil Rights Act of 1964,” “States in the Senate,” and “Women of the Senate.”

Since its founding, the Historical Office has developed and maintained a reputation among senators, staff, journalists, scholars, and the general public for providing fact-based, non-partisan information about the institution’s history. Its staff manage dozens of statistical lists and maintain information about senators and vice presidents in the online Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Historians lead custom tours for members and staff and deliver history “minutes”—brief Senate stories about a subject of their choosing—at the party conference luncheons and for the Senate spouses. They offer brown bag lunch talks, deliver committee and state legacy briefings, and host an annual Constitution Day event. Historical Office staff have provided background and research support for dozens of books on the Senate, as well as historic events such as inaugural ceremonies, three presidential impeachment trials, and the 1987 congressional session convened in Philadelphia to commemorate the bicentennial of the Great Compromise which paved the way for the signing of the U.S. Constitution.

In addition to these varied services, Senate historians have supported a number of projects for members and committees, including Senator Robert C. Byrd’s four-volume The Senate, 1789–1989; Senator Robert Dole’s Historical Almanac of the United States Senate; the executive sessions of the Committees on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (1953) and Foreign Relations (1947–1968); and Senator Mark Hatfield’s Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993. The Historical Office team has authored print publications including the United States Senate Election, Expulsion and Censure Cases, 1793–1990 (1995); 200 Notable Days: Senate Stories 1787–2002 (2006); Scenes: People, Places, and Events That Shaped the United States Senate (2022); and Pro Tem: Presidents Pro Tempore of the United States Senate (2024). The Office has helped to document party histories by editing the minutes of the Republican and Democratic Conferences and producing A History of the United States Senate Republican Policy Committee, 1947–1997. These publications have been illustrated, in part, with images drawn from the Historical Office’s rich photo collection.

During the past half-century, the Historical Office has adapted to meet the needs of an ever-evolving institution while continuing to provide the services first articulated by Secretary of the Senate Valeo in 1975. Today, its staff of 12 historians and archivists are dedicated to preserving and promoting Senate history for the next 50 years.

Notes

1. Letter from Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., to the Honorable Mike Mansfield, May 6, 1974, in Senate Historical Office files.

2. Senate Committee on Appropriations, Legislative Branch Appropriations for Fiscal Year 1976: Hearings on H.R. 6950, 94th Cong., 1st sess., April 21, 1975,1258.

3. Mack Thompson to Mr. Richard Baker, March 25, 1976, in Senate Historical Office files; “Senate Historian,” Roll Call, October 23, 1975; “Senate Office To Publish Declassified Documents,” New York Times, October 19, 1975.

4. "Richard A. Baker: Senate Historian, 1975–2009," Oral History Interviews, May 27, 2010, to September 22, 2010, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.; Richard A. Baker, “Managing Congressional Papers: A View of the Senate,” American Archivist 41, no. 3 (July 1978): 291–96.

|

| 202412 16When is a Senate First Truly a First?

December 16, 2024

In May 1971, newspapers heralded the end of a “boys-only” Senate page tradition with the appointment of three female pages. Senate historians have recently learned, however, that the Senate employed female pages at least as early as 1907. Emma Madeen served as a Senate riding page from June to December of that year, one of eight female riding pages who served between 1907 and 1926. The “discovery” of female riding pages in the early 20th century prompts a question: In an institution as old as the Senate, how can historians be certain that any event is a Senate “first”?

In May 1971 newspapers heralded the end of a long tradition when the Senate approved a resolution to allow the appointment of three female pages: Paulette Desell, Ellen McConnell, and Julie Price. “New Pages in Senate’s History: Girls,” announced the Washington Post. “Senate pages have always been boys, altho [sic] there is no regulation against the appointment of girls,” reported the Chicago Tribune.1

On one hand, the Tribune was correct. There had never been a rule prohibiting the appointment of female pages in the Senate. On the other hand, the story inaccurately identified Desell, McConnell, and Price as the first female Senate page appointments. While the efforts of these three teenagers who successfully petitioned for their appointments were historically significant at the time, Senate historians have recently learned that the Senate appointed female pages at least as early as 1907. Emma Madeen served as a Senate riding page from June to December of that year, one of eight female riding pages who served between 1907 and 1926. The “discovery” of female riding pages in the early 20th century prompts a question: In an institution as old as the Senate, how can historians be certain that any event is a Senate “first”?

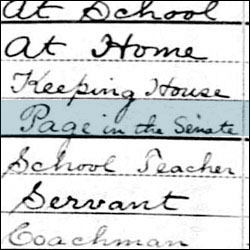

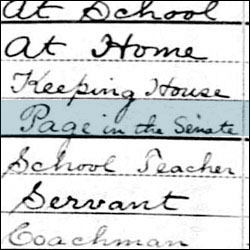

The appointment of Senate pages is one of the Senate’s oldest traditions. It began in 1824 when 12-year-old James Tims, the relative of Senate employees, was listed in the compensation ledger as “boy—for attendance in the Senate room.” In 1837 Senate employment records showed the position of “page” to identify young messengers who provided support for Senate operations. The titles and responsibilities of pages evolved with the institution. There were “mail boys” who helped with mail delivery, “telegraph pages” who delivered outgoing messages between the Capitol’s telegraph offices, “telephone pages” who received telephone messages, and “riding pages” who carried messages from the Senate to executive departments and the White House on horseback.

Though it is difficult to pinpoint the precise date of the Senate’s first riding page appointment, Senate records indicate that they served during the Civil War. An 1862 Senate expense report includes payment for the rental of two saddle horses and two letter bags for use by “riding pages.” During the war, riding pages delivered messages throughout Washington on horseback, a fast and relatively safe way to navigate a city pockmarked by open sewers, crisscrossed by muddy roads, and infiltrated by Confederate spies. The position continued long after the war. In 1880 Senate ledgers recorded back pay for riding page Andrew F. Slade, the first known African American page to serve in the Senate, and the title of “riding page” was listed on the secretary of the Senate’s report of expenses that year.2

By the late 1880s, riding pages did not rely solely on horses to navigate the city. The Senate appointed Carl A. Loeffler in 1889 as a riding page under the patronage of Senator Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania. When he arrived at the Senate, Loeffler learned that riding pages had recently experimented with using the city’s horse car system to deliver their messages. Horse-drawn trolley cars, or “horse cars,” were a popular mode of transportation in the 1880s, with systems in many large American cities, including New York, Boston, and Washington, DC. Horse cars allowed passengers to avoid walking on crowded and sometimes muddy streets. But riding pages needed to quickly deliver messages throughout the city’s federal departments and return promptly to the Capitol, and horse cars, which made frequent stops, proved to be an impractical option. By the 1890s, riding pages had largely abandoned the use of horse cars and, with Senate permission, adopted bicycles—the latest transportation innovation. However, Senate pages continued to deliver messages and packages on horseback through the 1910s, likely until the Senate formally closed its horse stables in 1914, as recorded in the secretary of the Senate’s annual report that year. The duties of the Senate riding pages have evolved alongside the Senate’s own evolving roles and responsibilities. By the 1950s, riding pages delivered messages to executive agencies by car, for example, making the position best suited for adult Senate staff. And while the role of the riding page has continued into the 21st century, modern Senate riding pages have not been a part of the Senate’s formal page program.3

Senate riding pages enjoyed many perks. In 1899 the annual salary for a riding page was $912.50, a considerable sum when compared with the salary of a Senate document folder ($840), or a laborer ($720). In addition to good pay, these teenagers also traveled about the city independently, escaping the watchful eyes of supervising adults for extended periods of time. Occasionally, when a favorite Senate Chamber page aged out of that program (in the early 20th century, 12- to 16-year-olds were eligible for the position), they transitioned to the riding page program.4

Much of what we know about the riding page position comes from one of the Senate’s many official records, the secretary of the Senate’s report of expenses, published annually (and later biannually). This report provides historians with a snapshot of the Senate community at a moment in time. The 1896 report, for example, includes all purchases and salaries paid that year, including one oak rocker for the Committee on Claims ($5.50), and a salary of $1,440 paid to S. F. Tappau for service as a messenger to that committee. That same year, the report documents salaries for four riding pages: M. S. Railey, J. A. Thompson, C. A. Loeffler, and Frank Beall. These detailed reports include the names of staff, their titles, and salaries, but do not categorize individuals according to race, ethnicity, or gender. To identify women on Senate staff, historians rely upon other clues, especially “gendered” first names, and turn to other sources, including census records, personal diaries, and newspaper accounts, in hopes of confirming personal details. As the 1896 report suggests, lists of names can be ambiguous when initials, rather than full names, are published. Additionally, feminine names can be difficult to trace through the years. When women marry, they often take their spouse’s surname, complicating efforts to document their full Senate employment record.5

Yet, even with these incomplete records, Senate historians can challenge some long-standing accounts of notable Senate “firsts.” During the summer of 1907, according to the secretary of the Senate’s report, the Senate employed four riding pages: F. Beall , Parker Trent, Albertus Brown, and E. Madeen. A subsequent report reveals that the initial E stands for “Emma.” Madeen may have been the first female page appointment, but no newspapers reported Madeen’s appointment as extraordinary at the time. Unfortunately, no official records provide historians with clues about Madeen’s life in the Senate, on Capitol Hill, or in Washington, DC. How old was she and how did she secure this job? In late December 1907, Helen Taylor replaced Madeen as a riding page. A year later, Taylor was joined by a second female page, Rose Baringer, and others followed. In addition to Madeen, Taylor, and Baringer, Flora White, Henrietta Greeley, Lucy Murphy, Mildred Larrazolo, and Marguerite Frydell served as Senate riding pages between 1907 and 1926.6

Senators and staff in 1971 may be forgiven for forgetting these female riding pages, who left the Senate 45 years before the Senate reportedly ended the “boys only” page tradition. But even this timeline is more complicated than it seems. From 1951 to 1954, both party cloakrooms employed women as their “chief telephone pages.” Operating out of the private spaces reserved for senators at the rear of the chamber, these women (census records indicate that they were likely adults, rather than girls or teens) answered incoming calls from staff in the Senate office building and provided critical updates about members’ whereabouts and the day’s scheduled floor proceedings and debates. Before technology allowed for the internal broadcasting of floor speeches over so-called “squawk boxes,” the Senate’s telephone pages helped to ensure the institution’s smooth operations and, as a constant presence in the cloakrooms, were likely recognizable. In 1971, when the Senate reportedly ended its “boys only” tradition, at least a dozen senators who voted on that proposal had served in the Senate from 1951 to 1954—when they had likely encountered these female telephone pages.7

Was Emma Madeen the first female page appointment? The answer may be yes—that is, until Senate historians find evidence of an earlier one!

Notes

1. Angela Terrell, “Girl Pages Approved,” Washington Post, May 14, 1971; “Fight for Senate Girl Pages,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1971.

2. J. D. Dickey, Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, D.C. (Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2014); “General of the Army: The Bill Passes Restoring the Title,” Atlanta Constitution, June 2, 1888.

3. Carl Loeffler unpublished memoir, Senate Historical Office files; John H. White, Jr., Horsecars, Cable Cars and Omnibuses (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1974); Senate Committee on Government Operations, “Special Senate Investigation on Charges and Countercharges Involving: Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens, John G. Adams, H. Struve Hensel and Senator Joe McCarthy, Roy M. Cohn, and Francis P. Carr, Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations,” 83rd Cong., 2nd sess., Part 1, March 16 and April 22, 1954, 35; “Security Minded CIA is so Secure Senator Can’t Get Letter to Director, Page Turned Back at Barricade,” Washington Post, June 11, 1963.

4. “California Boy Coolidge’s Page,” Boston Daily Globe, February 13, 1922.

5. Annual Report of William R. Cox, Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 55-1, 55th Cong., 2nd sess., December 6, 1897, 7–8.

6. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 60-1, 60th Cong., 1st sess., December 4, 1907, 26.

7. “Robert G. Baker: Senate Page and Chief Telephone Page, 1943–1953; Secretary for the Majority, 1953–1963,” Oral History Interviews, June 1, 2009, to May 4, 2010, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C., 14–15.

|

| 202402 28Integrating Senate Spaces: Louis Lautier, Alice Dunnigan, Thomas Thornton and Christine McCreary

February 28, 2024

African American men and women have worked on Capitol Hill since Congress moved to the new capital in the District of Columbia in 1800. Black laborers, enslaved and free, helped to build the Capitol. They worked as messengers, groundskeepers, carpenters, and cafeteria workers. In the 20th century, as African Americans moved into professional positions, they began to challenge inequality in their workplaces. Years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 legally ended segregation, four courageous individuals demanded the integration of Senate spaces.

African American men and women have worked on Capitol Hill since Congress moved to the new capital in the District of Columbia in 1800. Black laborers, enslaved and free, helped to build the Capitol. In the 19th century, African Americans worked as messengers, groundskeepers, pages, carpenters, and cafeteria workers. In the 20th century, as they began to move into professional positions, they challenged the discriminatory practices that prevailed in their workplaces. Years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 legally ended segregation, four courageous individuals demanded the integration of Senate spaces.

In January 1946, Louis Lautier, a correspondent for the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association, applied to the Senate Standing Committee of Correspondents for admission to the daily press gallery. In 1884 the Senate had made the Standing Committee, a group of elected members of the press gallery, responsible for credentialing congressional correspondents. Under Senate rules, the daily press gallery was open to correspondents “who represent daily newspapers or newspaper associations requiring telegraphic service.” Most African American papers were published weekly. A separate periodicals gallery served reporters of weekly magazines, not newspapers. Rules that seemingly were intended to prevent lobbyists from moonlighting as correspondents effectively made the Senate’s daily press gallery and the periodicals gallery off-limits to Black reporters. As Senate Historian Emeritus Donald Ritchie explains, “There [was] never a rule of the press gallery that says, ‘You have to be a white man,’ but the rules are written in such a way that that’s the only people who could get in.1

African American reporters had applied for admission on occasion despite these regulations, but their applications had all met the same fate—rejection. When rejecting Lautier’s application for admission in January 1946, the Standing Committee explained, “Inasmuch as your chief attention and your principal earned income is not obtained from daily telegraphic correspondence for a daily newspaper, as required under [Senate rules], you [are] not eligible.” Lautier then revised his application, noting that he was “jointly employed” by the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association, “with each organization paying half of my salary.” The Standing Committee stood by its initial decision, so Lautier appealed directly to the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, which had jurisdiction over the press galleries. The Rules Committee chairman, Democrat Harry Byrd of Virginia, did not intervene. Undeterred, Lautier resubmitted his application to the Standing Committee in November 1946.2

When the 80th Congress convened for its first session in January 1947, Republicans gained control of the Senate for the first time since 1933. One of the first orders of business facing the Senate was the seating of Senator Theodore Bilbo, a vocal white supremacist. In 1946 a Senate committee had investigated allegations by Black Mississippians that Bilbo had “conducted an aggressive and ruthless campaign” to deny Blacks the right to vote in the 1946 Democratic primary. A second, separate Senate inquiry had concluded that Bilbo had accepted “gifts, services, and political contributions” from war contractors whom he had assisted in securing government defense contracts. Lautier intended to cover the Senate debate, but without admittance to the press galleries, he was forced to wait in long lines for a seat in the public galleries, where Senate rules prohibited him from taking notes.3

Weeks later, on March 4, “after exhaustive deliberations and a personal hearing,” the Standing Committee again rejected Lautier’s application. Editorials in the national press urged the Standing Committee to reconsider its decision, and Lautier appealed to the new Rules Committee chairman, Senator C. Wayland “Curley” Brooks of Illinois. “Since the Standing Committee of Correspondents has acted arbitrarily in refusing me admission to the press galleries, and since under the interpretation of the rules Negro correspondents are barred solely because of their race or color, it appears that the Senate Rules Committee has the responsibility and duty to see that this gross discrimination against the Negro press is removed,” Lautier wrote.4

Senator Brooks, who had recently encountered separate allegations of racial discrimination in Senate facilities, readily agreed to investigate Lautier’s case. On March 18, 1947, Chairman Brooks convened a hearing to consider both Lautier’s application and the issue of discrimination in Senate dining facilities. “In the Capitol of the greatest free country in the world, we certainly should have no discrimination,” Brooks declared.5

The hearings first addressed Lautier’s application. Lautier testified that he met the qualifications for admittance to the daily press gallery under the existing rules. “I believe that I comply with the rules, if reasonably interpreted … because daily I gather news for the Atlanta Daily World.” While the rules had not been designed to “exclude Negro correspondents” from the press galleries “solely because of their race or color … that is the practical effect of the interpretation given the rules by the Standing Committee of Correspondents,” Lautier explained to committee members. Lautier described how the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association rendered a vital service to African Americans by focusing on issues of particular significance to them. At a recent hearing to consider amending the cloture rule, for example, Louisiana senator John Overton had stated that “the Democratic South stands for white supremacy.” Overton’s statement, as well as debates about proposed changes to Senate rules and procedures, had been “inadequately reported by the white daily press,” Lautier explained. His readers relied upon Black correspondents to be “intelligently informed of what is going on in the Congress.”6

Testifying in defense of the decision to deny Lautier’s admission, the chairman of the Standing Committee, Griffing Bancroft of the Chicago Sun, maintained that race had not played a role in its decision making and recommended a rules revision “so that facilities could be provided for the weekly papers.” Brooks pressed Bancroft; couldn’t the situation be immediately resolved by admitting Lautier? That is not a long-term solution, Bancroft replied, because without revising the rules for admission, African American correspondents writing for weekly papers would continue to be denied admission to the daily press gallery and the periodicals gallery. Lautier believed that a rules change would not be required in his case, because “under a reasonable interpretation of [the current] rules I am entitled to admission.” Members of the Rules Committee agreed with Lautier and voted unanimously to approve his application for admission to the Senate daily press gallery. It was only a partial victory for Black correspondents, however, as it was not clear if Lautier’s admission had paved the way for other Black reporters.7

At the same time that Lautier was appealing the decision of the Standing Committee for credentials to the daily press gallery, Alice Dunnigan, the new Washington correspondent for the Associated Negro Press, had just arrived in the city to cover the Bilbo floor debate. Unaware of the Lautier case, Dunnigan submitted applications to the Standing Committee for admission to the daily press gallery and to the periodicals gallery, but she waited weeks with no answer. She called repeatedly to inquire about her application and made personal visits to the Capitol, “probably making a nuisance of [herself].” Even after Chairman Brooks’s hearing on Lautier’s application, Dunnigan still did not get an answer. After some investigation, Dunnigan learned that she faced another kind of discrimination. The founder and director of her news organization, Claude Barnett, had failed to provide a letter of recommendation in support of Dunnigan’s application, as required by the Standing Committee. When Dunnigan confronted Barnett about the issue, he explained, “For years, we have been trying to get a [Black] man accredited to the Capitol Galleries and have not succeeded. What makes you think that you—a woman—can accomplish this feat?” Dunnigan persisted, however, and Barnett eventually sent his letter to the Standing Committee, who promptly approved her application for admission to the daily gallery in June 1947. “My acceptance received widespread publicity,” Dunnigan later recalled, “and the Republican-controlled Congress received credit for opening the Capitol Press Galleries” to African American reporters.8

Chairman Brooks’s hearing on the Senate press galleries had a positive impact on integrating those Senate spaces, but the fight to integrate the Senate’s dining facilities took a bit longer. Brooks had appointed World War II army veteran Thomas N. Thornton, Jr., an African American, to a position as a mail carrier in the Senate post office on February 20, 1947. One day in early March, Thornton stopped at the luncheonette in the Senate Office Building (now the Russell Senate Office Building) and ordered a sandwich and coffee. A waitress asked Thornton to take his order to go, but he refused, sat down at a table, and ate his meal. Though Senate rules prohibited discrimination in Senate facilities, Thornton had violated a long-standing Senate practice of “whites only” dining facilities. Word of Thornton’s actions spread, and Washington Post syndicated columnist Drew Pearson reported that Sergeant at Arms Edward McGinnis had reprimanded Thornton and advised him not to eat again inside Senate dining facilities. During the March 1947 Rules Committee hearings about discrimination in Senate facilities, the Architect of the Capitol, David Lynn, whose responsibilities included the operation of Senate restaurants, assured Chairman Brooks that discrimination in Senate dining facilities would not be tolerated. “When this incident happened, it was purely a misunderstanding on the part of a new [restaurant] employee or it would never have happened,” reported the director of Senate dining facilities, D. W. Darling.9

Despite these assurances, de facto segregation in the Capitol’s dining rooms persisted for years. Not long after joining Senator Stuart Symington’s personal staff in 1953, Christine McCreary attempted to eat in the Senate cafeteria. When an anxious hostess reminded her that the cafeteria served “only … people who work in the Senate,” McCreary explained, patiently, that she worked for Senator Symington. The hostess demurred, then reluctantly invited McCreary to “take a seat anyplace you can find.” Diners gawked as McCreary passed through the serving line with tray in hand. “You could hear a pin drop,” she later recalled. Silently enduring the “snide remarks” of those who disapproved of her effort, McCreary remembered her first years of Senate service as “a lonesome time.” But she refused to give up. “I went back [to the cafeteria] the next day, and the next day, until finally they got used to seeing me coming.”10

As we commemorate Black History Month, let us acknowledge the perseverance and determination of members of the Senate community, including Lautier, Dunnigan, Thornton, and McCreary, and their remarkable courage in challenging the Senate’s long-standing discriminatory practices.

Notes

1. Donald A. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 109–110; “Donald Ritchie, Senate Historian 1976–2015,” Oral History Interviews, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.

2. “Credentials,” January 1946, Louis Lautier Case, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office: Senate Press Gallery, Standing Committee on Correspondents.

3. Special Committee to Investigate Senatorial Campaign Expenditures, Investigation of Senatorial Campaign Expenditures, 1946, S. Rep. 80-1, 80th Cong., 1st sess., January 3, 1947; Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, Investigation of the National Defense Program, Additional Report, Transactions Between Senator Theodore G. Bilbo and Various War Contractors, S. Rep. 79-110, Part 8, January 2, 1947, 79th Cong., 2nd sess., 2; Donald A. Ritchie, Reporting from Washington: The History of the Washington Press Corps (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 35.

4. Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery and Hearing on Reports of Discrimination in Admission to Senate Restaurants and Cafeterias, 80th Cong., 1st sess., March 18, 1947, 5–6, 47–52.

5. Ibid., 70.

6. Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 4, 10; Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Amending Senate Rule Relating to Cloture: Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Rules and Administration on S. Res. 25, 30, 32, and 39, 80th Cong., 1st sess., January 28, February 4, 11, 18, 1947.

7. Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 9, 38.

8. Alice Dunnigan, Alone Atop the Hill: The Autobiography of Alice Dunnigan, Pioneer of the National Black Press (Athens: The University Press of Georgia, 2015) 107–9, 110–12; Ritchie, Reporting From Washington, 39–40; “Credentials,” January 1947, Alice Dunnigan Case, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office: Senate Press Gallery, Standing Committee on Correspondents.

9. Kenneth O’Reilly, “The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson,” Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 17 (Autumn, 1997), 117–21; Rodney Dutcher, “Behind the Scenes in Washington,” Times-News, Hendersonville, N.C., March 3, 1934; Drew Pearson, “Color Bar in Senate Restaurant,” Washington Post, 8 Mar 1947, 9; Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 61–64, 66; Report of the Secretary of the Senate, July 1, 1946, to January 3, 1947 and January 4, 1947, to June 30, 1947, S. Doc. 80-117, 80th Cong., 2nd sess., January 7, 1948, 260.

10. "Christine S. McCreary, Staff of Senator Stuart Symington, 1953–1977 and Senator John Glenn, 1977–1998," Oral History Interviews, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.

|

| 202310 10The First National Burial Ground: Congressional Cemetery

October 10, 2023

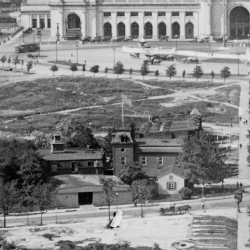

When Pierre L’Enfant produced his design for the new federal city in 1791, his plan did not include burial grounds. With the relocation of the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia set to happen by 1800, DC’s commissioners anticipated the influx of population that would follow and set aside land in 1798 for two cemeteries on the outskirts of the city, one on the west side and the other on the east. When the site on the east side of the city proved to be unsuitable for burials, a group of parishioners of Christ Church on Capitol Hill established a new burial ground two miles from the Capitol, known by the 1830s as Congressional Cemetery.

When Pierre L’Enfant produced his design for the new federal city in 1791, his plan did not include burial grounds. With the relocation of the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia set to happen by 1800, DC’s commissioners anticipated the influx of population that would follow and set aside land in 1798 for two cemeteries on the outskirts of the city, one on the west side and the other on the east. When the site on the east side of the city proved to be unsuitable for burials, a group of parishioners of Christ Church on Capitol Hill established a new burial ground along the Anacostia River, two miles from the Capitol. In time this cemetery came to be regarded as the first national burial ground, known by the 1830s as Congressional Cemetery.1

Just a few months after the Christ Church cemetery opened, Senator Uriah Tracy of Connecticut became the first member of Congress to be buried there. A Revolutionary War veteran and former president pro tempore of the Senate, Tracy died on July 19, 1807, and a few days later was interred in the cemetery “with the honors due to his station and character, as a statesman.” A member of the House of Representatives was buried there in 1808, and the following year Senator Francis Malbone of Rhode Island, who died on the steps of the Capitol after only three months in office, was interred there as well. Vice President George Clinton was interred there in 1812 and Vice President Elbridge Gerry followed in 1814, each escorted to his final resting place by a grand procession down Pennsylvania Avenue.2

The Washington Parish Burial Ground, as it was formally known at the time, was a public cemetery open to all, including African Americans (though in a segregated portion of the grounds). In addition to serving as the final resting place for some members of Congress, the cemetery also accommodated Senate officers, staff members, and even laborers who worked at the Capitol. William Swinton, a stonecutter who had worked on construction of the Capitol, was the first individual interred there in April 1807, just days after the cemetery was created. The Senate’s first doorkeeper and sergeant at arms, James Mathers, was laid to rest in the cemetery in 1811, as was the first secretary of the Senate, Samuel Otis, in 1814. Numerous members of the Tims family, who worked as doorkeepers, messengers, and pages in the early Senate, also found their final resting place in the cemetery.

During the early years of the 19th century, embalming practices did not allow for long-distance transportation of the deceased, making local burial a necessity. Consequently, when a member of Congress died during a congressional session, he was typically buried in a local cemetery. Between 1800 and 1830, practically every member of Congress who died in office was buried at this site. Facing this reality, in 1817 Christ Church donated 100 burial sites for the interment of representatives and senators. In 1820 it opened those sites to the families of members of Congress as well as the heads of cabinet departments. A few years later, the church provided 300 additional burial sites for members of Congress and government officials. Around this time, the site became popularly known as Congressional Cemetery.3

To give distinction to the gravesites of lawmakers, Congress in 1815 commissioned Capitol architect Benjamin Latrobe to design a stately monument to honor each of the deceased members. Latrobe’s design featured a large cube topped with a small, conical dome made from the same sandstone used to construct the Capitol. An engraved marble plaque identified the deceased. Latrobe believed the monuments would be more durable than the typical marble headstones in use at the time.

As years went by, improvements in embalming practices and in transportation—particularly with the construction of railroads—made it possible to return the deceased to home-state cemeteries. It became more common for members to be temporarily interred at the cemetery, then later transported for a home-state burial, leaving the space beneath the monument empty. For decades to come, Congress continued to add a monument to the cemetery whenever a member died in office, regardless of whether or not mortal remains ever rested there. By the 1870s, the cemetery held more than 150 of the Latrobe-designed monuments, arranged in long rows, although only about half actually covered a body. They became known as “cenotaphs,” which means “empty tomb.”4

Unfortunately, the stone markers weathered poorly over time and became increasingly unpopular with Washingtonians, including some members of Congress. One representative complained that the cenotaphs resembled a huge “dry-goods box with an old-fashioned bee-hive on top . . . , the most complete consummation of hideousness that it has ever been my misfortune to observe in a cemetery.” Above all, prayed another, “I hope to be delivered from dying—[at least] while Congress is in session.” When a bill was introduced in 1876 to require production of a granite monument matching the existing cenotaphs for future representatives and senators interred at the cemetery, Representative (and later Senator) George Hoar succeeded in striking the requirement from the bill. “It is certainly adding new terror to death,” Hoar stated, to require deceased members to lie beneath a cenotaph. This marked the end of new cenotaphs in Congressional Cemetery for nearly a century. A number of members of Congress were interred there in the years following, but those graves were marked with small headstones. One last cenotaph was placed in 1972 to mark the passing of House Majority Leader Hale Boggs who perished in a plane crash that year, his body never recovered.5

Though Congress did not have a formal relationship with Christ Church or ownership of the cemetery, it played an important financial role in the burial ground’s care and maintenance. Following the first congressional burials in the early 19th century, Christ Church officials hoped the donation of burial plots to Congress would strengthen ties with lawmakers and lead to financial support for the cemetery as a quasi-public institution. In 1824 Congress appropriated $2,000 to Christ Church to build a wall around the cemetery. Congress contributed more funds in the 1830s to build a house for the cemetery caretaker, plant trees, and “otherwise improve the interment of members of Congress and other officers of the General Government.” Between 1832 and 1834, Congress also appropriated $2,800 to build a vault to hold bodies awaiting burial, a service provided to representatives and senators free of charge. (Former First Lady Dolley Madison was interred there for three years while funds were raised to allow her to be moved for burial at her husband’s Montpelier estate in Virginia.) By 1846 Congress had appropriated $10,000 for upkeep and repairs. That year, when Congress provided funds for the cemetery and the road that led to from the Capitol, it used the name “Congressional Burial Ground,” solidifying its special relationship to the cemetery.6

With the establishment of Arlington Cemetery after the Civil War, Congressional Cemetery yielded its active role as the chief national burial ground. By that time, the cemetery had been the site for grand funeral services for deceased presidents William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and John Quincy Adams, and the final resting place of U.S. Attorney General William Wirt and U.S. Secretary of State John Forsythe. During the late 19th century, notable individuals from Senate and House history continued to be interred there, including former sergeant at arms Dunning McNair; Isaac Bassett, one of the first Senate pages and later a longtime doorkeeper of the Senate; Joseph Gales and William Seaton, early newspapermen who recorded congressional debates; and Anne Royall, one of the first women journalists to cover Congress. The cemetery also continued to serve private citizens well into the 20th century, eventually providing the resting place for 60,000 individuals, including pioneering photographer Matthew Brady, famed military composer and conductor John Philip Sousa, and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, a Washington native.

By the mid-20th century, Congress had long ceased providing appropriations for the cemetery, and Christ Church’s congregation lacked the resources to maintain it. Despite efforts by groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution to generate public and congressional support for the historic site, it gradually fell into disrepair. In 1976 a nonprofit organization, the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery (APHCC), assumed management of the site. After decades of neglect, however, the APHCC struggled to keep up with the overgrown grass and weeds, repair broken monuments and crumbling private vaults, and protect the grounds from vandalism. That year Congress passed legislation authorizing the architect of the Capitol to assist in the maintenance of the cemetery and appropriated funds for that purpose. Congress did not provide additional funds in the years following, however, and by 1997 Congressional Cemetery had fallen on such hard times that the National Trust for Historic Preservation added it to its list of most endangered historic sites. Neighborhood volunteers—especially dog owners who frequented the grounds with their pets and formed the K9Corps at Historic Congressional Cemetery—worked with the APHCC to raise money and devoted hundreds of hours to bringing the cemetery back to life. In 1997 volunteers from all five branches of the military gathered at the site to mow the grass and repair headstones, an event that continues to be an annual tradition. As the cemetery’s 200th anniversary approached, Congress once again provided monetary support, passing legislation in 1999 and 2002 to establish an endowment for its ongoing restoration and maintenance. The cemetery was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2011.7

Through the efforts of local volunteers and with funds appropriated by Congress, Congressional Cemetery, the first national burial ground, has been restored as both a meaningful community space and a monument to the elected officials who died while serving their nation in Washington, DC. Eighty-four representatives, fourteen senators, and five individuals who served in both houses of Congress are interred at Congressional Cemetery alongside the cenotaphs that memorialize the passing of dozens more.

Notes

1. Abby Arthur Johnson and Ronald Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol: Congressional Cemetery and the Memory of the Nation (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2012), 9–14.

2. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol, 23–24, 53–54.

3. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol, 35; Rebecca Boggs Roberts and Sandra K. Schmidt, Historic Congressional Cemetery (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2012), 7.

4. Roberts and Schmidt, Historic Congressional Cemetery, 25–27.

5. Congressional Record, 44th Cong., 1st sess., May 15, 1876, 3092–93; Kim A. O’Connell, “A Monumental Task,” Preservation (July/August 2009): 18–19; History of the Congressional Cemetery, S. Doc. 72, 59th Cong., 2nd sess., December 6, 1906, 35.

6. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol, 33, 36–37; History of the Congressional Cemetery, 11–15.

7. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol, 223–64; “Ruin of Tombs,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 31, 1890, 9; House of Representatives, Committee on Interior Affairs, “Relating to the Preservation of the Historical Congressional Cemetery,” H. Rpt. 667, 97th Cong., 2nd sess., July 27, 1982; Betsy Crosby, “To Hell and Back: The Resurrection of Congressional Cemetery,” Preservation (January/February 2012): 28–33; “The Cemetery Lost Its Aura,” Washington Star, September 19, 1971, 1; “New Panel Eyes Cemetery Bill,” Washington Post, July 28, 1976, A15; “A Gentle Reminder of Congressional History, 20 Blocks from Capitol Hill,” Roll Call, September 18, 1988, 31; “Congressional Cemetery Could Get Funding,” Roll Call, July 26, 2001, 46.

|

| 202303 08Enriching Senate Traditions: The First Women Guest Chaplains

March 08, 2023

The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857, and for more than 100 years, guest chaplains had all been men. That changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition.

The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. All Senate chaplains have been men of Christian denomination, although guest chaplains, some of whom have been women, have represented many of the world's major religious faiths.

The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857. That year, with many senators complaining that the position had become too politicized, the Senate chose not to elect a chaplain. Instead, senators invited guests from the Washington, D.C., area to serve as chaplain on a temporary basis. In 1859 the practice of electing a permanent chaplain resumed and has continued uninterrupted since that time, but the practice of inviting a guest chaplain to occasionally open a daily session also continued. While it is possible, and perhaps likely, that the Senate selected guest chaplains prior to 1857, surviving records from the period are insufficient to make that determination.

By the mid-20th century, guest chaplains were frequently offering the Senate’s opening prayer. Clergy visiting the nation’s capital often communicated their desire to serve as a guest chaplain to their home state senators who would nominate them for the role. In the 1950s, this practice became so popular among senators that Chaplain Frederick Brown Harris, who served nearly 25 years as Senate chaplain, complained to Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas that guest chaplains had replaced him 17 times over the course of just a few weeks. Leader Johnson assured Harris that he would ask senators “to restrict the number of visiting preachers,” but the frequency of the guests persisted.1

During the 1960s, Harris suffered from a series of medical issues and was less engaged in his official duties. Consequently, Harris’s unplanned absences prompted new problems for the Senate majority leader, now Mike Mansfield of Montana, whose staff was forced to arrange for last-minute guest chaplains. Infrequently, they called on senators to offer the prayer. Further irritating the majority leader, Harris unwittingly hosted guest chaplains who used the “forum to present their own particular litanies” and political viewpoints, thereby violating the Office of the Chaplain’s tradition of nonpartisan, nonpolitical service.2

Such issues prompted Senate leaders to reevaluate policies related to the appointment of guest chaplains. When Reverend Harris passed away in early 1969, Majority Leader Mansfield and Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois created an informal, bipartisan committee on the “State of the Senate Chaplain.” Upon concluding their study, the leaders informed Harris’s successor, Chaplain Edward L. R. Elson, of a policy change: “It would be our judgement that under ordinary circumstances a regular practice of inviting two guest chaplains per month is now in order.” Also, “In instances when you are ill or unavoidably absent, we would expect you to ask a brother clergyman to fill in temporarily in your stead.” The new policy was intended to standardize and bring order to the guest chaplain practice.3

For more than 100 years, guest chaplains had been men, but that changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition. A 1942 graduate of the Union Theological Seminary, Rowland became a minister in 1957, after the Presbyterian Church allowed for the ordination of women. She was an author and associate minister in Cincinnati, Ohio, before joining the United Presbyterian Board of Christian Education in Philadelphia, where she directed its educational loans and scholarships program. When Chaplain Elson invited her to lead the Senate’s opening prayer, Rowland recognized the historical significance of his offer. “It’s an honor to pray with and for such an august body,” she explained to the press. “I’m not unmindful of the women’s lib[eration] angle to my performance. But the prayer, like any other I have offered, is still to God. I’ve kept that in mind while I’ve been working on it.”4

Generally, the opening of the Senate’s daily session is sparsely attended. Six senators were present in the Chamber on July 8, 1971, for this historic event, including the Senate’s only woman senator, Margaret Chase Smith of Maine. Senate President pro tempore Allen Ellender of Louisiana called the Senate to order at noon, then introduced Dr. Rowland as “the very first lady ever to lead the Senate in prayer.” Rowland began:

O God, who daily bears the burden of our life, we pray for humility as well as forgiveness. As our nation plays its part in the life of the world, help us to know that all wisdom does not reside in us, and that other nations have the right to differ with us as to what is best for them.

Rowland later reflected on the event: “I’m pleased not for myself but for the fact the Senate has reached the point where they feel it is normal to invite a woman to do this.”5

But it wasn’t normal yet, and three years would pass before another woman delivered the Senate’s opening prayer. On July 17, 1974, Sister Joan Doyle, president of the Congregation of Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary headquartered in Dubuque, Iowa, became the second woman and the first Roman Catholic nun to offer the opening prayer in the Chamber. Her sponsor, Iowa senator Dick Clark, introduced her. At the conclusion of Doyle’s prayer, Minority Leader Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania praised her “gentler touch” for preparing senators to enter “into the brutal conflicts of the day.” Senator Margaret Chase Smith had retired in 1973, and Senator Clark reflected on the lack of women senators in the Chamber that day. “I hope it won’t be three more years before another woman is here, not only for the opening prayer, but as a member of the Senate.” It took more than five years, in fact, for the next woman senator to take a seat in the Chamber. On January 25, 1978, Muriel Humphrey was appointed to fill the seat left vacant when her husband, Senator Hubert Humphrey, passed away.6

Since 1974 other women have followed in the footsteps of Reverend Rowland and Sister Doyle, although the number of female guest chaplains remains small. In 2008 the Reverend Dr. Patricia Bryant Harris made history as the first African American woman to give the Senate’s opening prayer. “It had a lot of meaning to me personally, to be a part of that history,” Reverend Harris said in an interview. “That is now history as part of the Congressional Record.”7

The chaplain has been an integral part of the Senate community since the election of the first chaplain, Samuel Provoost, on April 25, 1789. Today, chaplains and guest chaplains, now men and women, deliver the opening prayer each day that the Senate is in session. As Senator Mary Landrieu of Louisiana remarked in 2012, "It is good that we take a moment before each legislative day begins in the Senate to still ourselves and ask for God's grace and guidance on the work that we have been called to do."8

Notes

1. Congressional Record, 91st Cong., 2nd sess., August 20, 1970, 29611.

2. “Chaplain Absent, Senator Gives Prayer,” Hartford Courant, September 20, 1963, 25B; “Senator Takes Chaplain’s Place,” Washington Post, Times Herald, September 2, 1964; Memorandum from Richard Baker to Mike Davidson, September 19, 1985, in the files of the Senate Historical Office.

3. Mike Mansfield and Everett Dirksen to Dr. Edward L. R. Elson, Chaplain, April 29, 1969, in the files of the Senate Historical Office.

4. “Barrier to Fall: Woman Will Lead the Senate in Prayer,” Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), July 4, 1971, A-10; “A Woman, Praying for the Senate,” Washington Post, July 9, 1971, B2.

5. Congressional Record, 92nd Cong., 1st sess., July 8, 1971, 23997; “Barrier to Fall: Woman Will Lead the Senate in Prayer.”

6. “Nun Gives Prayer in Senate,” Catholic Standard, July 25, 1974.

7. Nicole Gaudiano, “Del. Pastor makes history in U.S. Senate,” News Journal (Wilmington, DE), July 11, 2008, B1.

8. “At Sen. Landrieu’s Invitation, Louisiana Chaplain Offers Opening Prayer for U.S. Senate,” Targeted News Service, Feb. 28, 2012.

|

| 202202 02Celebrating Black History Month

February 02, 2022

To celebrate Black History Month, the Senate Historical Office presents stories, profiles, and interviews available on Senate.gov that recognize the many contributions of African Americans to the U.S. Senate and the integral role they have played in Senate history.

To celebrate Black History Month, the Senate Historical Office presents stories, profiles, and interviews available on Senate.gov that recognize the many contributions of African Americans to the U.S. Senate and the integral role they have played in Senate history.

Shortly after the Civil War, Hiram R. Revels (1870) and Blanche K. Bruce (1875) of Mississippi set historic milestones as the first African Americans to be elected to the Senate. It would be nearly another century—not until 1967—before Edward W. Brooke of Massachusetts followed in their historic footsteps. In 1993 Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois became the first African American woman to be elected to the Senate. To date, 11 African Americans have served as U.S. senators. In 2021 California senator Kamala D. Harris resigned her Senate seat and took the oath of office as the nation’s 49th vice president, thereby becoming the first African American to serve as the president of the Senate.

The role of African Americans in Senate history extends beyond those who served in elected office. One of their earliest and most enduring contributions came with the construction of the U.S. Capitol. Although historians know little about the laborers who built the Capitol, evidence shows that much of that labor force was African American, both free and enslaved. Many years later, Philip Reid, an enslaved man, brought to the Capitol the mechanical expertise needed to separate and then cast the individual sections of the Statue of Freedom, which was placed atop the Capitol Dome in 1863.

African Americans also worked in and around the Senate Chamber in the 19th century. Tobias Simpson, for example, was a messenger from 1808 to 1825. His quick action during the British attack on the Capitol in 1814 saved valuable Senate records, and he was subsequently honored with a resolution (and a pay bonus). His role in that record-saving endeavor was described in an 1836 letter written by Senate clerk Lewis Machen. Another example was a young African American boy named William Hill. In the winter of 1820, senators counted on the warmth provided by fires tended by Hill, who was paid $37 for his services by Sergeant at Arms Mountjoy Bayly.

Several African Americans employed by the Senate became trailblazers. In 1868 Senate employee Kate Brown sued a railroad company that forcibly removed her from a train after she refused to sit in the car designated for Black passengers. Brown’s case eventually made it to the Supreme Court, which ruled in Brown’s favor in 1873. The first African American to join the Senate’s historic page program, Andrew F. Slade, was appointed in 1869 and served until 1881. John Sims, known by his contemporaries as the “Bishop of the Senate,” built relationships with senators in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as both a Senate barber and a popular Washington, D.C., preacher.

The first African Americans to be hired for professional clerical positions appeared in the early 20th century, including Robert Ogle, a messenger and clerk for the Senate Appropriations Committee, and Jesse Nichols, who served as government documents clerk for the Senate Finance Committee from 1937 to 1971. Senate staff members Thomas Thornton and Christine McCreary and news correspondent Louis Lautier challenged the de facto segregation of Capitol Hill in the 1940s, '50s and '60s. In 1985 Trudi Morrison became the first woman and the first African American to serve as deputy sergeant at arms of the Senate. Alfonso E. Lenhardt, who served as sergeant at arms from 2001 to 2003, was the first African American to hold that post. The Senate appointed Dr. Barry C. Black as Senate chaplain on July 7, 2003, another first for African Americans. On March 1, 2021, Sonceria Ann Berry became the first African American to serve as secretary of the Senate.

These are just a few milestones among many. As research continues, Senate historians are discovering other stories of African Americans who have played a unique and integral role in Senate history.

|

| 202106 01Shaving and Saving: The Story of Bishop Sims

June 01, 2021

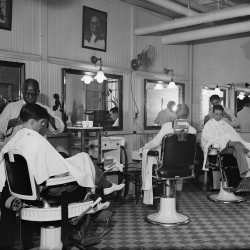

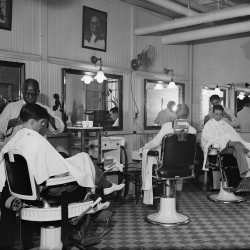

As a child, having been born into slavery in 1843, John Sims was forced to train the bloodhounds his master used to track runaway slaves. When the Civil War began in 1861, the teenaged Sims escaped bondage and fled north. When he died 73 years later, Sims was a beloved and well-known figure on Capitol Hill, a friend and confidant of some of the most powerful men in Washington. He is largely forgotten today, because John Sims wasn’t a powerful senator or a high-profile member of Capitol Hill staff—he was the Senate’s barber.

As a child, having been born into slavery in 1843, John Sims was forced to train the bloodhounds his master used to track runaway slaves. When the Civil War began in 1861, the teenaged Sims escaped bondage in his native South Carolina and fled north. When he died 73 years later, Sims was a beloved and well-known figure on Capitol Hill, a friend and confidant of some of the most powerful men in Washington. Despite his impressive rise from the bonds of slavery to the corridors of power, he is largely forgotten today. That’s because John Sims wasn’t a powerful senator or a high-profile member of Capitol Hill staff—he was the Senate’s barber.1

Sims’s dangerous flight to freedom landed him in the town of Oskaloosa in southeast Iowa. He arrived with no funds and no marketable skills, but he managed to find work in a barbershop. An apprenticeship followed and soon he was earning a living as a skilled barber. Then, in the mid-1880s, came the first of two fateful senatorial encounters—when Iowa senator William Boyd Allison got a haircut.

Throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th century, many Senate jobs were filled through patronage. Senator Allison, who chaired the Appropriations Committee, had plenty of patronage to give. He brought Sims to the Senate, where the barber’s tonsorial talents gained recognition. Sims “knows the whims [and] the vanities” of the Senate, reported the New York Times. His skill with shears and razor kept him employed long after his patron was gone, but it was Sims’s weekend job and a second notable encounter that brought him to public attention.2

John Sims moonlighted as a preacher at the Universal Church of Holiness in Washington, D.C. One day in 1916, Ohio senator (and future president) Warren G. Harding sat in the barber’s chair. “Sims,” he said, “I’m coming down next Sunday to hear you preach.” A few days later, to the surprise of the entirely African American congregation, Senator Harding attended the service. “He walked in by himself,” Sims recalled, “and took a seat near the middle of the church and waited until I was through.” When the service ended, Harding thanked Sims and returned to the Capitol to spread the news of the preaching talents of the Senate barber.

A week later, Harding returned to the Universal Church of Holiness and brought several of his colleagues with him. As the years passed, more and more senators appeared. Vice Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Charles Dawes also attended. “From the North, from the South, from the East and the West they have come to hear me,” Sims explained. “And to think that I have come up from a lowly place of humility . . . to where I have the honor of preaching to those who are high in the nation’s affairs!” Sims insisted that he owed it all to Harding. “He started it all—and the Senators have been coming to hear me ever since.”

The preaching barber became known as the “Bishop of the Senate.” His prayers, noteworthy for both length and fervor, also enlivened his official Senate duties. “[If] he thought the occasion required [it],” commented a reporter, Sims would “drop to his knees . . . in the midst of . . . a shave and pray with all his heart” for the senator sitting in his chair. In 1921, as the Senate prepared to vote for its next official chaplain, Senator Bert Fernald of Maine asked, “Can we vote for anybody who has not been placed in nomination?” With an affirmative answer to his question, he cast his vote for John Sims, although the post went to the Reverend Joseph J. Muir.3

Bishop Sims was strictly nonpartisan and loyally supported all of his patrons at election time. When two of his favorite Senate clients—Democrat Joseph T. Robinson of Arkansas and Kansas Republican Charles Curtis—competed for the vice presidency in 1928, Sims fervently prayed for each to win their party’s nomination. His prayers were answered. The two men faced each other in the general election. “Who are you for [now],” Robinson asked the barber, “myself or Senator Curtis?” “I prayed for your nominations,” Sims replied diplomatically, but now “you gotta hustle for yourself.”

John Sims achieved success, as barber and as preacher, but one cherished goal remained elusive—to pray in an open session of the Senate. “Sims cannot die happy unless he has had at least one chance to shrive the Senate,” reported the Baltimore Sun in 1928. “For many years he has been longing to be allowed to open one of the Senate sessions with a prayer.” That year, it looked as if the 85-year-old preacher’s wish would finally come true. With the second session of the 70th Congress set to convene in December, a senator pledged to invite him to give the daily prayer, but no record of such an occasion has been found. It seems that wish remained unfulfilled.4

Rising from slavery to become friend and confidant of senators, vice presidents, and presidents, John Sims remained on duty in the Senate barbershop until his death at age 91. Even after he retired from active barbering and served only as supervisor, he reported to work every day, preaching to the Senate community. Eventually, age and illness took their toll and kept Sims away from the Capitol, prompting senators to visit him at his home where they could still count on his advice and encouragement. “Don’t you worry,” Sims reassured Minnesota senator Henrik Shipstead during one of his visits to the sickbed, “I will be back in the barbershop in a couple of days.” When Sims passed away on March 29, 1934, Shipstead echoed many of his colleagues when he described the preaching barber as “the most beloved and popular man on Capitol Hill.”5

A reporter once asked Sims to explain the secret of his popularity among senators. I’m just “shaving and saving,” Sims responded. Give a good shave, and always preach salvation.6

Notes

1. “Senate Barber Preaches: Sermons of John Sims, Once a Slave, Are Heard by Many of His Tonsorial Patrons,” New York Times, September 5, 1926, 10.

2. “Rev. John Sims Has Shaved Four Decades of Senators,” New York Times, April 21, 1929, 150.

3. “Senate Barber Preaches: Sermons of John Sims, Once a Slave, Are Heard by Many of His Tonsorial Patrons,” 10; “Fernald Votes for Negro for Chaplain of Senate,” Boston Daily Globe, January 22, 1921, 12; “Odd Items from Everywhere,” Boston Daily Globe, December 14, 1923, 32.

4. “A Strange Ambition,” Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1928, 8; “Senate May Hear Negro Barber Pray at Session,” Washington Post, July 1, 1928, A10; “Aged Barber to Officiate over Senate,” Chicago Defender, July 21, 1928, A1; “Rev. John Sims Has Shaved Four Decades of Senators.”

5. “Bishop Sims,” South Carolina Genealogy Trails, accessed April 26, 2021, http://genealogytrails.com/scar/bio_bishop_sims.htm.

6. “Negro Barber’s Wish to Pray in U.S. Senate to Be Fulfilled,” Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1928, 13.

|

| 202104 01Saving Senate Records

April 01, 2021

Today, records of Senate committees and administrative offices are routinely preserved at the Center for Legislative Archives, a division of the National Archives. This wasn’t always the case. For more than a century, precious documents were stashed in basement rooms and attic spaces. In 1927 a file clerk named Harold Hufford discovered a forgotten cache of records in the basement. Cautiously opening a door, he disturbed mice and roaches to find a document signed by Vice President John C. Calhoun. “I knew that the nation’s documents shouldn’t be treated like that,” Hufford remarked, and the modern era of Senate archiving was born.

Staff and visitors to the Senate may occasionally see carts containing gray manuscript boxes in the hallways of Senate office buildings. Very likely they are viewing Senate committee records on their way to or from the Center for Legislative Archives (CLA) at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Within NARA, the CLA is the custodian of thousands of linear feet of Senate textual records and terabytes of electronic data. Noncurrent Senate committee records are boxed up and sent to NARA when the committee no longer needs immediate access to the materials. And, once archived, these records are also loaned back to the Senate when needed for reference, and made available to scholars and researchers after a closure period of at least 20 years. While these and other Senate records have long been cared for and kept secure, in the long history of the Senate, it wasn’t always this way.

In the Senate’s earliest days, the person responsible for safeguarding the ever-expanding collection of records—including bills, reports, handwritten journals, the Senate markup of the Bill of Rights, and George Washington's inaugural address—was Secretary of the Senate Samuel A. Otis. Sam Otis died in April 1814, just months before a contingent of British troops invaded the capital city and set fire to the White House, the Capitol, and other federal buildings. Fortunately, when word reached Washington on August 24, 1814, that British troops would soon occupy the city, Lewis Machen, a quick-thinking Senate clerk, and Tobias Simpson, a Senate messenger, hastily loaded boxes of priceless records onto a wagon and raced to the safety of the Maryland countryside. Nearly five years later, when the Senate returned to the reconstructed Capitol from temporary quarters, a new secretary of the Senate moved the records back into the building. With space at a premium in the Capitol, however, these founding-era documents, as well as those created in the remaining decades of the 19th century, ended up being stored in damp basements, humid attics, closets, and even behind Capitol walls. And those were the records that had been saved; countless documents had been lost or damaged over time, some falling victim to autograph hunters who snipped the signatures of presidents from their messages to Congress.1

The Senate’s records remained in this state until Secretary of the Senate Edwin P. Thayer, whose term began in 1925, found an original copy of the Monroe Doctrine in the Senate financial clerk's safe. This discovery sparked his interest in preserving additional Senate records that were scattered throughout the basement storerooms of the Capitol. In 1927 Thayer hired Harold E. Hufford, a young George Washington University law student, as a file clerk to find these dispersed and neglected materials and put them in order. Hufford famously recounted going down into the brick-lined rooms of the Capitol basement in search of documents. After cautiously opening a door, disturbing mice and roaches in the process, and walking across the room to turn on a light, he looked down and found a document underfoot; on it was the imprint of his shoe and the signature of Vice President John C. Calhoun. “I knew who Calhoun was,” Hufford said, “and I knew that the nation’s documents shouldn’t be treated like that.” Hufford spent the next six years at the Senate working tirelessly to locate, organize, and index these valuable records, including the first Senate Journal from 1789 and the Senate markup of the Bill of Rights—some of the very same records that Machen and Simpson had saved more than a century earlier.2

Meanwhile, as Hufford labored over the Senate’s neglected documents, construction began on a building to house federal records. Legislation authorizing and funding a national archives had been years in the making, finally culminating in the 1926 Public Buildings Act. The groundbreaking for the National Archives building took place on September 5, 1931, on Pennsylvania Avenue between 7th and 9th Streets Northwest. As one of his last acts as president, Herbert Hoover laid the cornerstone on February 20, 1933.3

Building the National Archives was one thing, but filling it up and running it was quite another. In March 1934 a bill to establish the National Archives as the agency that would manage, preserve, and make available the nation’s federal records was referred to the Senate Committee on the Library, chaired by Tennessee senator Kenneth McKellar. Reporting the bill back to the Senate in May, McKellar called it “one of the most important matters that has been before the Senate for some time.” By June the House and Senate conferees had agreed unanimously on the final report. The bill passed both houses of Congress and on June 19, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Archives Act into law. The legislation created the Office of the Archivist of the United States, with an archivist appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, to oversee all records of the government—legislative, executive, and judicial.4