By the time the Senate welcomed the first female senator in 1922, women were already playing a groundbreaking role on Senate staff. Women began working on Senate staff, typically in custodial positions, as early as the 1850s, but by the dawn of the 20th century they were assuming increasingly important roles in senators’ offices and committees. These pioneering women challenged gender stereotypes, overcame societal and institutional obstacles, and opened doors for others to follow. Each and every one of them had a hand in shaping the history of the Senate and the nation.

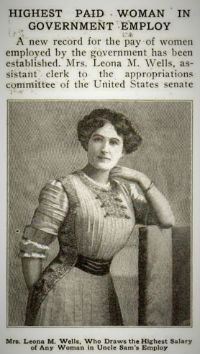

Among the earliest pioneers was Leona Wells, who joined Senate staff in 1901 and remained on the payroll for the next 25 years. Born in Illinois around 1878, Wells moved to Wyoming when she turned 21 (because this young suffragist could cast a vote in Wyoming). There she met Senator Francis E. Warren, whose patronage brought her to Washington, D.C. She served as messenger and assistant clerk to several committees. When Senator Warren became chairman of the Committee on Appropriations in 1911, he assigned to Wells the management of all committee business, although she never gained the official title of clerk—forerunner to today’s chief clerk position. Wells wasn’t the first woman to hold a clerical position for a Senate committee, nor the first to be lead clerk, but she was the first to assume that responsibility for such a powerful committee as Appropriations.1

At the time, Leona Wells was unusual—a well-paid professional woman on Capitol Hill. In fact, she was so unusual that she attracted media attention. Leona Wells “is probably the most envied woman in government service,” reported the Boston Globe in 1911. Not only did she earn a good salary, the Globe noted, but she is “placed in charge of the affairs of a big committee.” Wells scouted new territory for female staff, but one area remained off-limits—the Senate Chamber. When Chairman Warren was on the floor handling committee business, Wells had to wait outside. Male committee clerks freely entered the Chamber, but the Senate was not yet ready to admit a female staffer to its inner sanctum. Instead, as the Globe reported, Wells waited “just outside the swing doors of the senate chamber . . . and kept the door an inch or two ajar that she might hear everything that went on inside.”2

Soon, other women set their own milestones. By 1917 five women served as top clerk on Senate committees, including Jessie L. Simpson, clerk for the Committee on Foreign Relations. Raised in St. Louis, Simpson actively participated in the presidential campaign for Woodrow Wilson in 1912, where she caught the attention of Missouri senator William Stone. Simpson joined the Senate staff that year through Stone’s patronage, serving as messenger and clerk to several committees before joining the staff of the Foreign Relations Committee in 1914. Having served as assistant clerk, Simpson gained the top committee job in 1917 with an annual salary of $3,000. (At that time, senators received a salary of $7,500.)

News reporters took note of the accomplishment, but they often commented not on Simpson’s abilities but on her fitness for such a sensitive job. “It’s an old story that a woman can not keep a secret,” commented one, “but here is one who must keep many,” who must “go through what is described as an ordeal for her sex” to keep diplomatic secrets. Despite the attention, Simpson took it in stride. “I can’t see why all this fuss about my being appointed to the clerkship,” she stated. “I’ve been acting clerk for months. It’s merely a question of my appointment being made permanent.” As the committee’s top clerk, the New York Times reported, Simpson took on tremendous responsibilities. “In her hands will be treaties with foreign Governments . . . and much other information of a delicate nature.” Like Leona Wells, Jessie Simpson proved that women in government service could tackle difficult jobs with great skill, but she didn’t stay in the position long. In November of 1917, Simpson relinquished her well-paying Senate job to “do her bit” for the war effort. She became a clerk for the U.S. Department of War in France.3

By this time, a growing number of women were taking jobs in the Senate. As early as 1904, news accounts had noted that some “of the best paid employees of our government are women.” Many came to Washington, D.C., during the First World War to fill jobs held by men who had joined the war effort, while others came seeking employment that would be long-lasting. “Is Washington in danger of being overrun by women?” asked a reporter for the Washington Post in 1917. By the 1920s, women filled a number of top positions in senators’ offices and in committees. In 1922 six Senate committees employed women as principal clerks, and many other women served as assistant clerks. In fact, that year, at least 82 of the Senate’s 154 committee clerks listed in the Congressional Directory—53 percent—were women. Four Senate committees were staffed entirely by women.4

Among those six chief clerks was Mabelle J. Talbert. Hired by Nebraska senator George Norris in 1915, Talbert moved with Norris through several committees. When he became chairman of the Committee on Agriculture in 1921, Talbert signed on as assistant clerk. A year later, she became clerk in charge of all committee operations, including management of investigative hearings into such issues as the meat-packing industry and shipment of “filled” or adulterated milk (declared illegal in 1923). Like a number of other top female staff at the time, Talbert served in dual roles in the Senate, as lead clerk to a committee and as secretary to the committee chairman. Norris once described his secretary as a “trusted lieutenant” who “knew the ground and understood the nature of the opposition forces and weapons.”5

Cora Rubin, in 1922 the clerk for the Education and Labor Committee and also secretary to Idaho senator William Borah, became a well-known figure on Capitol Hill. An Idaho native, Rubin first worked for Borah when he was a lawyer in their home state. When the state legislature elected Borah to the Senate in 1906, Rubin followed him to Washington to serve as his stenographer, then as secretary, and by 1920 also was in charge of a major committee. In her dual capacity, Rubin assumed so much responsibility that the press dubbed her “deputy senator.” One Borah biographer described her as the “Cerberus who guarded the office door.”

Regardless of her position and decades of service on Capitol Hill, Rubin still faced persistent institutional barriers, such as Chamber access. As committee clerk she held floor privileges but was wary of exercising them, as she explained, “because of the notoriety that would follow.” Although this has been difficult to document, Rubin most likely overcame that hesitation. “I have promised myself that before I leave here for good,” she told a reporter in 1922, “I am going to walk right in on the floor of the senate when it is in session and watch the grave and reverend senators fall over at such desecration!” It would take many years for the “masculine precinct” of the Senate Chamber, as the New York Times described it in 1929, to be fully breached by women staff.6

Another milestone came in 1926 when Mary Jean Simpson became the Senate’s first female bill clerk. Sponsored by Vermont senator Porter Dale, Simpson was no newcomer to politics and public service. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1913 and became active in politics in her home state of Vermont. She participated in various wartime efforts and served in local and state elective offices. Serving as Senate bill clerk until 1933, Simpson later led Vermont’s emergency relief efforts during the Great Depression, directed the women’s division of the Vermont Works Progress Administration, and then became dean of women at the University of Vermont. Today, that university awards an annual prize in honor of this one-time Senate pioneer, the Mary Jean Simpson Award, to a female student “who best exemplifies the qualities of character, leadership, and scholarship.”7

As the role of women on Senate staff grew, Lola Williams took those trailblazing efforts a step further and made history in 1929. “For the first time,” reported the New York Times, “a woman is serving as secretary to the Vice President.” This long-time secretary to Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas achieved that milestone when Curtis took the oath of office as vice president on March 4, 1929, thereby becoming the constitutional president of the Senate. Curtis enthusiastically extolled Williams’s intelligence and experience, but press coverage of her groundbreaking move focused more on appearance than ability. “Miss Williams has one salient characteristic, essentially feminine,” remarked an Associated Press reporter, “for all her efficiency, she wears clothes well and is good to look upon.” As the vice president’s chief aide, Williams oversaw correspondence between Curtis and President Herbert Hoover and managed all official business while the vice president presided over the Senate. A woman had “never appeared in such an official capacity,” noted the Times.8

Earlene White was also a pioneer, although much of her story remains a puzzle. Born in Mississippi, White began her career as a newspaperwoman in Jackson and then went into public relations. It is unclear what brought White to the nation’s capital, but that move may have coincided with her becoming president of the National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs in 1937. By that year, she also served as a mail carrier in the Senate, and by the end of that decade news accounts consistently identified her as Senate postmaster. Senate employment records do not assign that title to her; rather, they list her as mail carrier throughout her Senate career.

Whether she enjoyed the title of postmaster or not, White was a powerhouse. In addition to her Senate duties, she continued to lead national women’s rights organizations. Advancement of the Equal Rights Amendment and equal opportunities in the workplace became her principal goals. “I ask each of you within sound of my voice,” White proclaimed to a large audience in 1938, “to take a pledge that we will not rest until the women of all the nations enjoy political opportunities. . . . We must think how best to advance women for high political and appointive office.” When White died in 1961, the Washington Post described her as “a fighter for the rights of women” and as the “former postmistress of the Senate.” Was Earlene White the de facto postmaster without a title, just as Leona Wells had been de facto lead clerk of a committee without that title? That remains a mystery, but there is no question that she was one of the Senate’s female pioneers.9

It took much longer for women of color to find their place on the Senate’s professional staff. Although African American women had been Senate employees for a century, not until the 1950s did they likely gain professional positions on committees or in senators’ offices. One of the earliest was Christine McCreary, who joined the staff of Missouri senator William Stuart Symington in 1953. When McCreary came to Capitol Hill, she not only faced lingering resistance to women in top staff positions, but also a racially segregated workplace. In an oral history interview with the Senate Historical Office, McCreary recalled the frightening experience of being among the first to challenge segregation in Senate spaces. “I didn’t know what to expect,” McCreary remembered, “because you see Washington was segregated and you had to deal with that.” Facing segregation in the Senate cafeteria, for example, McCreary courageously demanded to be served, and refused to give up. “I went back the next day, and the next day, until finally they got used to seeing me coming in there.” McCreary remained on Senate staff until 1998.10

For many years, scholars studying Congress paid scant attention to Capitol Hill staff, and those who did assumed that women played little or no role on Senate staff before the Second World War. As research continues, Senate historians are discovering that women held positions of influence, on committee staff and in senators’ offices, early in the 20th century. This important role of the “Women of the Senate” is not a recent phenomenon but a story encompassing more than a century of Senate history.

Notes

2. Annual Report of Charles G. Bennett, Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 57-1, 57th Cong., 2nd sess., December 2, 1902; Annual Report of the Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 62-954, 62nd Cong., 3rd sess. December 4, 1912; “Is Suffragette Uncle Sam’s Highest Salaried Woman,” Boston Daily Globe, August 6, 1911, SM11; “Is Best-Paid Woman,” Washington Post, May 28, 1911, M1; “Women Who Count,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 24, 1911, J11.

3. Report of the Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 65-309, 65th Cong., 3rd sess., December 2, 1918; “Important Post for Woman: Miss Jessie L. Simpson Appointed Clerk to Senate Foreign Relations Committee,” New York Times, January 3, 1917, 10; “First Woman Secretary of Senate Committee,” Boston Daily Globe, January 3, 1917, 11; “Going to the Front,” Los Angeles Times, November 21, 1917, I1; “Drops Honor for War,” New York Times, November 13, 1917, 5; “Pretty Girl Custodian of Important Secrets,” Knoxville Sentinel, February 8, 1917, 9.

4. Congressional Directory, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., December 1921, 232–33; 67th Cong., 4th sess., December 1922, 234–35; “Women Crowding to Washington to Fill Government Jobs of Men Gone to Fight Nation’s Battles,” Washington Post, June 17, 1917, SM4; “Women. Government Employs a Large Number,” Boston Daily Globe, May 22, 1904, 55.

7. The Mary Jean Simpson archival collection is housed in Special Collections of the University of Vermont Libraries in Burlington, VT; “Grafton ‘Old Home’ Day,” Christian Science Monitor, August 21, 1925, 3; “Miss Mary Jean Simpson to Aid on Women’s Project,” Washington Post, October 4, 1936, M14; “WPA Consultant Accepts Deanship,” August 6, 1937, 3.

9. Report of the Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 76-136, 76th Cong., 3rd sess., January 11, 1940; “City Club Dinner Party Will Honor Miss White,” Washington Post, August 11, 1935, S7; “Senate Postmistress is Nominated for President of Professional Women’s National Federation,” Washington Post, July 23, 1937, 17; “Earlene White in 2d Address,” Washington Post, August 5, 1938, 15; “Guest Speaker,” Washington Post, September 13, 1938, 20; “Hill B. & P. W. Forms Branch,” Washington Post, August 2, 1939, 13; “Earlene White, Woman Leader,” Washington Post, February 23, 1961, B3; “Colonials Hear Earlene White,” Washington Post, April 18, 1941, 17.