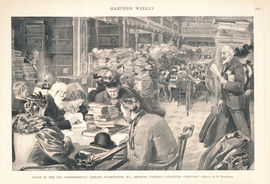

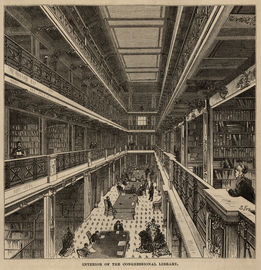

Of the many historical images in the U.S. Senate Collection that depict the Library of Congress in the Capitol Building, one 1897 Harper’s Weekly illustration stands out for its particularly chaotic depiction of the space. As the caption indicates, the scene portrays the institution’s “present congested condition” in the months just prior to the library’s relocation to its own building across the street. The illustration by artist William Bengough teems with visitors. Men and women, young and old, occupy every seat visible in the image and navigate mountainous piles of books and papers stacked high on the floor and on nearly every horizontal surface. In the background, the library’s innovative cast-iron architecture can be glimpsed above and behind the disorder of the central vignette. Though the library soared some 38-feet high, Bengough crops the vertical space, contributing to the claustrophobic scene. For all of this visual confusion, however, the illustration reveals at least three truths about the Library of Congress during its years in the Capitol (1800–1897): 1) it exceeded its founding purpose and served as an important public resource, 2) the library rapidly outgrew its physical spaces as its collections expanded, and 3) it was one of the Capitol’s architectural gems.

At the time of its founding, the library was intended to serve a narrower, albeit significant, purpose. Section 5 of the April 24, 1800, act relocating the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to Washington established the library. It appropriated $5,000 “for the purchase of books as may be necessary for the use of Congress at the said city of Washington, and for fitting up a suitable apartment [in the Capitol] for containing them.” Though its collections started small and its intended audience was “both houses of Congress and the members thereof,” within its first decades in the Capitol, the library’s holdings had grown in size and public importance. At the same time, its “suitable apartment” in the building grew in size and architectural stature.1

Bengough’s illustration shows the last of several Capitol spaces occupied by the Library of Congress. The library’s first two decades required it to be portable and adaptable. Though the founding act called for “fitting up a suitable apartment” to house the library’s collections, its books were first stored in the office of the Clerk of the Senate. It was not until 1802 that the library’s collections of 964 volumes and 9 maps were relocated to a large, two-story room in the northwest corner of the Capitol, a space that had most recently served as a temporary House Chamber. Just three years after moving into the new location, however, the library was asked to remove its collections to a committee room on the south side of the library so that the House could reconvene in the space. In a November 1808 report, architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who was hired by President Thomas Jefferson to oversee construction of the Capitol, observed that the committee room was already “much too small” and that the books were “piled up in heaps,” a situation that would certainly cause the “utmost embarrassment.”2

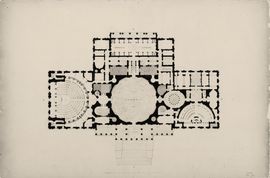

Despite Latrobe’s concerns, it was not until a devastating fire set by British troops at the Capitol on August 24, 1814, destroyed much of the building and completely consumed the library that it finally received a dedicated space. Congress acted quickly to replenish the Library of Congress’s holdings by purchasing the personal library of President Jefferson, but it took nearly a decade to rebuild the library itself. Congress asked Latrobe to create more committee rooms in the building’s north wing for the Senate’s use, and the architect decided to repurpose the space previously occupied by the library to fulfill Congress’s request. His March 1817 plan of the Capitol’s principal floor relocated the library to the west side of the Capitol’s center building. Architect Charles Bulfinch, who stepped in after Latrobe’s November 1817 resignation, defined the new library’s design and saw it to completion. Opened on August 17, 1824, the new library was widely recognized for its grandeur and refinement. As one commentator observed soon after the room opened, “The new Library Room is admitted, by all who see it, to be, on the whole, the most beautiful apartment in the building. Its decorations are remarkably chaste and elegant, and the architecture of the whole displays a great deal of taste.”3

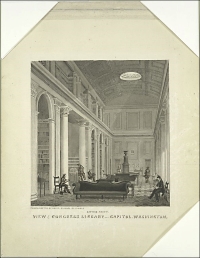

The only known image of Bulfinch’s design for the Library of Congress, an 1832 view by architect Alexander Jackson Davis and artist Stephen Gimber, emphasizes the library’s impressive architecture and portrays it as a comfortable space for visitors. Four deep alcoves filled with books, as well as a second-story gallery with additional book storage, are visible along the left-hand side of the image. Monumental columns frame the library’s east and west entrances. The room is well appointed with large sofas, reading tables, and side chairs. One of the neoclassical iron stoves designed by Bulfinch to heat the room is visible in the image, towering over the library’s patrons. Architect Robert Mills remarked upon the public use of the space in 1834, “The valuable privileges afforded all, whether residents or strangers, who come properly introduced, are properly appreciated; for the room is usually well filled, during the hours it is accessible, both with ladies and gentlemen.” Thus, it is clear by this time that the library was frequently used by men and women of the public, albeit with the restriction that they “come properly introduced.”4

Despite its many amenities, Bulfinch’s library was largely constructed of wood, and the threat of fire was a persistent source of concern. The space survived one on December 22, 1825—scarcely 16 months after it had opened—when a patron left a candle burning in the gallery after the library closed for the evening. The conflagration destroyed many of the books on the gallery level (most of which were duplicates of books stored elsewhere), but firefighters were able to extinguish the flames before they reached the ceiling’s large wooden trusses. This contained the fire to the library and prevented its spread to the Capitol’s dome. This near-disaster led to discussions about how to fire-proof the library, but the required fixes were deemed prohibitively expensive. Unfortunately, a second fire, sparked by a faulty flue leading from a fireplace in a room below, completely destroyed the library on December 24, 1851. Some 35,000 volumes—approximately three-fifths of the collections—as well as many priceless artworks burned. News of the fire traveled quickly, and the Cleveland Daily Herald reported—even before the fire had been extinguished—that the destruction of the library “cannot be regarded otherwise than as a great national calamity.” Though it had been founded as a library for the use of Congress, by the time of the 1851 fire, according to the newspaper, “it had become eminently creditable as a National Library.”5

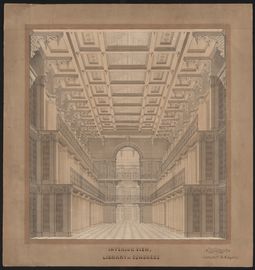

Moving rapidly to rebuild, Congress called upon architect Thomas U. Walter, who was working on the Capitol extension, to design the world’s first completely fireproof library. With amazing speed, just 24 days after the fire, Walter provided architectural plans, sections, and elevations for a new library that was revolutionary in its use of cast-iron, a strong, noncombustible material that could be shaped into delicately ornamented panels. The library had three stories of tiered alcoves and galleries with cast-iron shelving. Recessed cast-iron semicircular staircases located at each end of the room enabled patrons to ascend to the upper levels. Large foliated pendants supported the weight of the cast-iron ceiling, the first in the United States to be constructed of this material. Marble, another fireproof medium, was selected for the flooring. With a robust appropriation of $75,000 from Congress, the library, as Harper’s New Monthly Magazine described it, “rose, phoenix-like, from its ashes.” A “large number of ladies and gentlemen” reportedly gathered for the library’s public reopening on August 23, 1853, and spectators were amazed by its iron architecture, describing it as “unsurpassed for its beauty and elegance.”6

Two large extensions added in 1867 to the north and south ends of the main hall tripled the library’s physical size and greatly expanded its capacity from 38,000 to 134,000 volumes. Such a substantial expansion was necessary to accommodate the rapid growth of the collections, which more than quadrupled in size from a reported 86,414 volumes in 1864 to 374,022 volumes by 1879. This tremendous increase was driven by several significant acquisitions and purchases, including a large transfer from the Smithsonian Institution library in 1866, as well as the 1870 Copyright Act, which required all materials copyrighted in the United States to be deposited with the Library of Congress.7

Throughout this period, commentators remarked on the library’s popularity with the public. In 1872 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine reported that it was almost impossible to “visit the library at any time when its doors are open without finding from ten to fifty citizens seated at the reading-tables, where all can peruse such books as they may request to have brought to them from the shelves.” The accompanying illustration presents a view of the library, looking down from the lower gallery. It shows patrons using the library’s collections at each level. People are depicted reading, but also socializing (as in the group of three chatting prominently in the foreground) and people-watching (as in the woman pictured on the right-hand side of the image, who gazes toward a man on the opposite side of the library at the left). The article emphasizes the public’s generous access to the Library of Congress and even claims, “The library is thus thrown open to any one [sic] and every one, without any formality of admission or any restriction.”8

Illustrators had the advantage of being able to represent the social aspects of visitors’ engagement with the library in ways not easily achieved in other media. Though the space was often reproduced photographically in popular stereographs during the late 19th century, the limitations of shutter speed during this period meant that people using the library—who possibly weren’t even aware that a photograph was being taken—appear blurry and indistinct. A stereograph of the Library of Congress published by J. F. Jarvis exemplifies the ghostly appearance of the library’s patrons. Though many are seated at reading tables, they elude the camera’s quest for fixity by flipping newspaper pages and shifting in their seats. The fleeting impressions of people in the space contrast with the tremendous detail that the camera captures of the library’s static and seemingly permanent fireproof architecture.

A close examination of the first gallery level of the library in this stereograph reveals piles of books and papers stacked high on the gallery floor. Once again, the library was stretched beyond capacity. By 1875 Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford reported that the institution had run out of shelf space, and that books, maps, and other collection items were “being piled upon the floor in all directions.” Four years prior, anticipating the spatial limitations of the Capitol, Spofford had proposed constructing a dedicated building for the Library of Congress in a separate location. In 1886 Congress authorized construction of what is now the Library of Congress’s Jefferson Building across the street from the Capitol.9

The Library of Congress remained in the Capitol until its new building opened on November 1, 1897. The large cast-iron rooms formerly occupied by the library remained in place until June 1900, when Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the Architect of the Capitol to reconstruct the space into three floors, with rooms on two of the floors split evenly between the House and the Senate and the third floor turned into a shared reference library. The ironwork—once considered an architectural marvel—was dismantled and sold at auction for scrap. By 1901 evidence of the Library of Congress in the Capitol had largely vanished. Only traces remained in the building’s fabric, including the library’s black and white marble flooring, which was reused in the corridor one floor below.10

The early history of the library serves as a reminder that, when walking the halls of the Capitol today, it is easy to forget such spaces—even those, like the library, that were once considered among the building’s architectural gems. Historical prints and photographs in the U.S. Senate Collection can help us to remember and revisit the Library of Congress and other sites in the Capitol that are no longer extant. Additional historical images of the Library of Congress, as well as depictions of other interior Capitol spaces, are available on the Senate website.

Notes

2. An Act concerning the Library for the use of both Houses of Congress, 2 Stat. 128 (January 26, 1802); Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, The Original Library of Congress: The History (1800–1814) of the Library of Congress in the U.S. Capitol, report prepared by Anne-Imelda Radice, 97th Cong., 1st sess., 1981, 2, 5–7. Latrobe quoted in U.S. House of Representatives, Documentary History of the Construction and Development of the United States Capitol Building and Grounds, 58th Cong., 2nd sess., H. Rpt. 646, 148.

3. William C. Allen, History of the United States Capitol: A Chronicle of Design, Construction, and Politics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 109; Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Original Library of Congress, 26; “Congressional Library Room,” Wilmingtonian and Delaware Register, January 6, 1825.

7. “The Library of Congress,” 48; US Senate, Office of Senate Curator, Isaac Bassett Manuscript Collection, Box 8, Folder C, p. 125, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Isaac Bassett Manuscript Collection, Box 13, Folder C, p. 58a; An Act to provide for the Transfer of the Custody of the Library of the Smithsonian Institute to the Library of Congress, 14 Stat. 13 (April 5, 1866); An Act to revise, consolidate, and amend the Statues relating to Patents and Copyrights, 16 Stat. 198 (July 8, 1870).