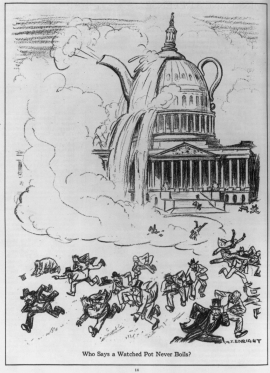

A century ago, in June 1924, the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys released a report, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, that outlined one of the worst breaches of the public trust in American history. The Senate investigation into the scandal, popularly known as Teapot Dome and led by Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, uncovered widespread corruption between government officials and powerful corporate interests. The inquiry serves as a powerful example of effective congressional oversight, highlighting the ability of lawmakers to expose wrongdoing to protect the public interest.

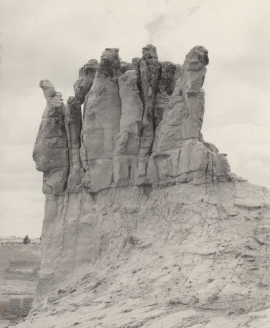

The seeds of the Teapot Dome scandal were planted in the first decade of the 20th century, when President Theodore Roosevelt and conservationists in Congress took steps to protect public lands from unlimited private exploitation. Concerned with ensuring the national government had access to energy resources and anticipating the conversion of the nation’s naval fleet from coal-burning to oil-burning power, Roosevelt instructed the U.S. Geological Survey to survey oil reservoirs beneath public lands. In 1909 President William Howard Taft responded to the Survey’s findings by signing an executive order withdrawing three million acres of public lands in California and Wyoming from private settlement and development and designating portions of these public lands in California, known as Elk Hills and Buena Vista, as naval oil reserves. In 1915 President Woodrow Wilson added a third naval oil reserve in Wyoming, named Teapot Dome after a sandstone rock formation that resembled a teapot. Congress by law in 1920 placed these reserves under the supervision of the secretary of the navy, who was given wide latitude “to conserve, develop, use, and operate the oil reserves” in the national interest.1

In the years after the reserves were created, the nation’s largest oil companies began plotting to obtain leases for drilling. The amount of oil in the reserves, and the money that could be made by extracting it, was staggering. Surveys estimated that the three reserves combined held 435 million barrels of oil, almost equal to the total amount of oil that had been produced in the country to that point. Extracted, those resources were estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, at least a billion in today’s dollars.2

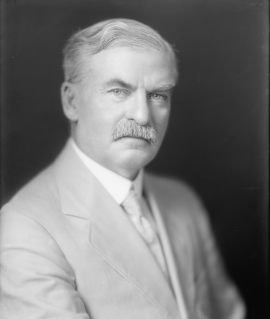

In 1921 Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall was also keenly interested in the reserves. Fall was a former gold and silver prospector and attorney who had been elected to serve as one of New Mexico’s first senators in 1912. Known for his volatile personality and his frontiersman ways—he reportedly often carried a six-shooter pistol—Fall enjoyed the support of prominent industrialists who had helped finance his 1918 re-election campaign and provided backing for Fall’s purchase of a prominent Albuquerque newspaper. In the Senate, Fall became friends with fellow Republican senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio (who had joined the Senate in 1915), the two bonding over whiskey and poker games—then a popular Washington pastime. When Harding was elected president in 1920, he nominated Fall to be his secretary of the interior. Fall had plans to open the nation’s public lands to private development, and he persuaded the president to place the naval reserves under his control. On May 31, 1921, Harding signed an executive order transferring control of the naval reserves from the Navy Department to the Interior Department.3

Rumors swirled for months about Fall’s plans to develop the reserves. On April 12, 1922, Fall offered to his friend Harry F. Sinclair, the head of Sinclair Oil, an exclusive, no-bid lease for the Teapot Dome oil reserves. Intending to keep the deal a secret, Fall locked the contract in his desk and instructed the assistant secretary to tell no one about it. But intrepid reporters soon uncovered the story. On April 14, 1922, the Wall Street Journal ran a front-page exposé detailing the sweetheart deal. The Denver Post was not far behind, offering details about what it called “one of the baldest public land-grabs in history.”4

Independent oil producers saw the press coverage and, angry at not having had an opportunity to bid on the leases, complained to Wyoming Democratic senator John B. Kendrick about the secret negotiations of the Teapot Dome deal. When Kendrick inquired about the details of the lease from the Interior Department, Fall’s subordinates gave him the runaround. On April 15, Kendrick introduced a resolution in the Senate instructing the secretaries of the interior and the navy to inform the Senate about any ongoing negotiations for leases on Teapot Dome. Now under intense pressure, Fall released a statement to the press on April 18 announcing the Teapot Dome lease and disclosing the impending completion of another lease for the Elk Hills reserve to oil baron Edward Doheny and his Pan-American Oil Company. On April 20, Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, a progressive Republican and a leading conservationist in the Senate, introduced a resolution demanding from the Interior Department all documents relating to the negotiation and execution of leases on the naval oil reserves. The Senate amended the resolution to authorize the Committee on Public Lands and Surveys to conduct a full-scale investigation and approved it by unanimous vote (with 38 senators not voting) a week later.5

In early June, Fall submitted to President Harding a 75-page report and thousands of supporting documents detailing the history of the naval oil reserves and the geological data that Fall claimed justified the leases. Harding sent the report to the Senate with a memo stating that all policies regarding the reserves had been reviewed by him and “at all times had my entire approval.”6

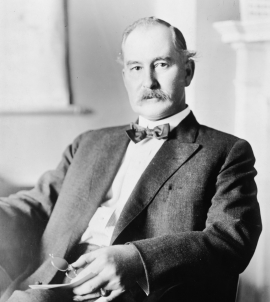

The Teapot Dome investigation was slow to get off the ground. The first challenge was getting someone to lead it. While La Follette had been the driving force to authorize the inquiry, he was not a member of the Committee on Public Lands. The Republican chair of the committee was Reed Smoot of Utah, a conservative who was not enthusiastic about pursuing an investigation that could be politically damaging for his party. John Kendrick served on the Public Lands Committee but did not want to take on the task. La Follette and Kendrick persuaded Democrat Thomas Walsh of Montana to lead the investigation.

The son of Irish Catholic immigrants, Walsh had been an attorney in Helena, Montana, before becoming a powerful force in the state’s Democratic Party. Elected to the Senate in 1912, Walsh had a reputation as an able lawyer and a progressive willing to take on the powerful mining interests in his state. Walsh was the most junior member of the minority party on the committee, but the ranking Democrat was leaving the Senate after 1922, and La Follette and Kendrick opted to bypass the other more senior Democrats. Walsh was not a conservationist and had, to that point, been a supporter of opening up public lands—and Native American reservations—for resource exploitation. He was initially reluctant to commit to the investigation, but after some prodding from fellow Montana Democrat Burton K. Wheeler, he agreed in June 1922 to wade in and began reviewing the mountain of documents submitted by Fall.7

Walsh worked through the evidence methodically throughout the summer and fall of 1922, and by early 1923, he began to suspect that Fall had engaged in misconduct. In February 1923, with the Senate set to adjourn in March, the Public Lands Committee set a hearing date for October, a little more than a month before the 68th Congress would convene in December. By the time Walsh returned to Washington in September to begin preparing for the hearing, Albert Fall had resigned from the cabinet to go work for Sinclair, President Harding had died of a heart attack, and Vice President Calvin Coolidge had become president.8

When the hearings began on October 23, 1923, the main question facing the committee was whether Albert Fall was justified in secretly leasing the naval reserves without competitive bidding. Chairman Smoot called the committee to order and then turned over the proceedings to Walsh, who took the lead in questioning witnesses. In the opening round of questioning, Walsh challenged Fall on the legality of Harding transferring control over the naval reserves to him as secretary of the interior and argued that Congress had clearly intended for the secretary of the navy to be the steward of its oil. Fall contended that the president was in his rights to give him responsibility over the reserves. He defended his quick action in granting leases as necessary to prevent the reserves from being depleted by drainage—the intentional depletion of reserves by adjacent landowners. Reports from the Bureau of Mines had indicated that drainage was not a concern, but geologists hired by the committee at the behest of Chairman Smoot disagreed, claiming that the reserves were draining at a rapid rate and that only 25 million barrels of oil remained. Under questioning, Fall defended his selection of Sinclair as a sound business decision and the deal’s secrecy as a matter of national security. Smoot opined that “if the reports of the experts are accepted, the theory that the government made a mistake in leasing this reserve has been exploded.”9

Walsh had other sources, however, that opened up new avenues of investigation. Journalists from Denver and New Mexico—including Carl Magee, who had purchased Fall’s newspaper from him in 1920—told Walsh about a suspicious, abrupt change in Fall’s personal finances. Brought before the committee on November 30, Magee testified that Fall had been cash-poor in 1921 and a decade in arrears on the property taxes of his dilapidated New Mexico ranch. But in June 1922 Fall, suddenly flush with cash, paid his back taxes, purchased neighboring properties, and made substantial improvements to his previously rundown ranch. The burning question became, where did Fall get all of this money?10

By the time Walsh completed his questioning of witnesses in January 1924, he had uncovered suspicious payments made to Fall. Harry Sinclair gave Fall $269,000 in Liberty Bonds and cash a month after signing the Teapot Dome lease. Edward Doheny, to whom Fall awarded the Elk Hills reserve lease, testified that he instructed his son to deliver $100,000 (well over $1 million in today’s money) in cash to Fall “in a little brown satchel,” allegedly as a loan, but one that Fall had lied about and tried to conceal from Walsh and the committee. In a closed committee meeting, Walsh informed his colleagues that he would be introducing a resolution directing the president to appoint a special counsel to bring civil suits to cancel the naval reserve leases and to pursue criminal charges connected to awarding the leases. Republican Irvine Lenroot, now chair of the Public Lands Committee, informed President Coolidge of Walsh’s intentions and urged him to get out in front of the news. On January 27 Coolidge announced his intent to appoint counsel and file charges, and a few days later the Senate passed Walsh’s resolution.11

Walsh was not done with his investigation, however. What had begun in late 1923 as a quiet set of hearings in a small committee room soon became a public sensation with audiences packed into the spacious Caucus Room on the third floor of the Senate Office Building. Walsh recalled Fall to face more questioning, but Fall delayed, claiming ill health. When he finally returned on February 2, 1924, Fall refused to answer any additional questions, claiming his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself and further arguing that the imminent appointment of special prosecutors ended the committee’s authority over the case. When Sinclair came back for more questioning in March, he refused to answer questions as well, though he didn’t bother to cite his Fifth Amendment rights. “There is nothing in any of the facts or circumstances of the lease of Teapot Dome which does or can incriminate me,” he stated. The Senate referred contempt charges against both Fall and Sinclair to the District of Columbia courts.12

The Public Lands Committee concluded its hearings in May 1924, and a bipartisan majority issued its final report in June, signed by Edwin Ladd of North Dakota, who had become committee chair in March. Some senators and representatives, particularly Democrats, criticized the report for its lack of drama and its failure to draw conclusions about the corrupting influence of oil interests in government. Still, the report included additional evidence of corruption, including Sinclair’s payments to buy off rival claimants to the reserves, as well as a $1 million payment to newspaper publishers in exchange for their silence when they discovered the shady circumstances surrounding the Teapot Dome lease.13

The committee noted “rumors” of a broader conspiracy on the part of prominent oil companies to place Harding in the White House and Fall in the Interior Department for the very purpose of exploiting natural resources on public lands but concluded only that “the evidence failed to establish the existence of such a conspiracy.” Five Republicans on the committee, led by Smoot, issued a minority report complaining that the majority had not given them time to review the report and all the supporting evidence. In January 1925, a minority of the committee issued a more substantive report defending many aspects of the Harding administration’s handling of the naval reserves and criticizing Walsh for dedicating space in the report to what it saw as baseless rumors about political conspiracies. Historians who have dug into the scandal have since given these theories more credence.14

Civil and criminal litigation involving the oil reserve leases dragged on for the next six years, with several cases going before the Supreme Court. In the end, the government proved that the leases had been illegally obtained and successfully regained control of the naval reserves. Fall was found guilty of accepting a bribe from Sinclair and sentenced to a year in prison, the first cabinet official in U.S. history to be convicted of a felony. Juries acquitted Sinclair and Doheny on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government, however. Sinclair served prison time for contempt of court—he was found guilty of attempting to intimidate the jury in his criminal trial—and contempt of Congress. The Supreme Court heard his appeal, upheld his conviction, and recognized the Senate’s investigatory power and its authority to compel testimony from witnesses. In another contempt case arising out of a related investigation into Harding administration corruption, the Court held in the McGrain V. Daugherty decision, “We are of opinion that the power of inquiry—with process to enforce it, is an essential and appropriate auxiliary of the legislative function.”15

The Teapot Dome scandal cast a long shadow over American politics, for decades serving as a symbol of the highest form of government corruption. Lawmakers investigating charges of corruption in the decades that followed the scandal would inevitably make the comparison, warning the public that they may find evidence of “another Teapot Dome” or something “worse than Teapot Dome.” In 1950, commenting on the development of the western United States, President Harry Truman stated, “The name Teapot Dome stands as an everlasting symbol of the greed and privilege that underlay one philosophy about the West.” In 1973, as Watergate coverage flooded the national media, some reporters called it “the new Teapot Dome.” “For half a century, [Teapot Dome] has, for many Americans, represented the quintessence of corruption in government,” wrote one correspondent. “Now Teapot Dome has been shoved aside by contemporary events.”16

For the Senate, the Teapot Dome investigation firmly established the authority of Congress to question the executive branch and demand information about its operations. Senator Walsh’s diligent and tenacious search for the truth uncovered corruption and held the government accountable to the people it serves, setting a standard for future Senate investigations to emulate.

Notes

1. Hasia Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” in Congress Investigates: A Critical and Documentary History, vol. 1, eds. Roger Bruns, David Hostetter, and Raymond Smock (Byrd Center for Legislative Studies, 2011), 460; Laton McCartney, The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Bought the Harding Whitehouse and Tried to Steal the Country (New York: Random House, 2019), 28–29, 96.

2. Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves: Hearings Pursuant to S. Res. 282, S. Res. 294, and S. Res. 434, 68th Cong., October 31, 1923, 678. Experts of the time disagreed as to how much oil was held in the reserves. The Bureau of Mines estimated that Teapot Dome held 135 million barrels of oil, for example, but geologists employed by the Committee on Public Lands estimated it at only 12 to 26 million. These estimates turned out to be very low. The Elk Hills reserve alone has yielded more than a billion barrels of oil in the century since. “Elk Hills Is Source of Controversy,” New York Times, April 1, 1975, 10.

11. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, January 24, 1924, 1772; Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” 466–68; Joint Resolution Directing the President to institute and prosecute suits to cancel certain leases of oil lands and incidental contracts, and for other purposes, Public Resolution 68–4, 68th Cong., 1st sess., February 3, 1924, 43 Stat. 5.

15. McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135, 174 (1927); Jake Kobrick, “United States v. Albert B. Fall: The Teapot Dome Scandal,” Federal Judicial Center, accessed June 26, 2024, https://www.fjc.gov/history/cases/famous-federal-trials/us-v-albert-b-fall-teapot-dome-scandal.

16. “Teapot Dome Likeness Seen in Radio Lobby,” Washington Post, January 12, 1937, 24; “War Assets Scandal Seen,” Baltimore Sun, June 19, 1946, 4; “Power Pact Likened to Teapot Dome,” Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1955, 1; “Pledge Given by Truman to Develop West,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1950, 1; “Watergate Joins Teapot Dome in US Scandal Vocabulary,” Christian Science Monitor, May 9, 1973, 7; Lee Roderick and Stephen Stathis, “Today Watergate—Yesterday Teapot Dome,” Christian Science Monitor, July 17, 1973, 9.