Staff and visitors to the Senate may occasionally see carts containing gray manuscript boxes in the hallways of Senate office buildings. Very likely they are viewing Senate committee records on their way to or from the Center for Legislative Archives (CLA) at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Within NARA, the CLA is the custodian of thousands of linear feet of Senate textual records and terabytes of electronic data. Noncurrent Senate committee records are boxed up and sent to NARA when the committee no longer needs immediate access to the materials. And, once archived, these records are also loaned back to the Senate when needed for reference, and made available to scholars and researchers after a closure period of at least 20 years. While these and other Senate records have long been cared for and kept secure, in the long history of the Senate, it wasn’t always this way.

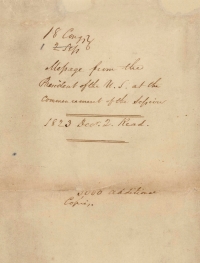

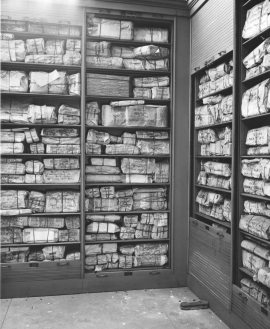

In the Senate’s earliest days, the person responsible for safeguarding the ever-expanding collection of records—including bills, reports, handwritten journals, the Senate markup of the Bill of Rights, and George Washington's inaugural address—was Secretary of the Senate Samuel A. Otis. Sam Otis died in April 1814, just months before a contingent of British troops invaded the capital city and set fire to the White House, the Capitol, and other federal buildings. Fortunately, when word reached Washington on August 24, 1814, that British troops would soon occupy the city, Lewis Machen, a quick-thinking Senate clerk, and Tobias Simpson, a Senate messenger, hastily loaded boxes of priceless records onto a wagon and raced to the safety of the Maryland countryside. Nearly five years later, when the Senate returned to the reconstructed Capitol from temporary quarters, a new secretary of the Senate moved the records back into the building. With space at a premium in the Capitol, however, these founding-era documents, as well as those created in the remaining decades of the 19th century, ended up being stored in damp basements, humid attics, closets, and even behind Capitol walls. And those were the records that had been saved; countless documents had been lost or damaged over time, some falling victim to autograph hunters who snipped the signatures of presidents from their messages to Congress.1

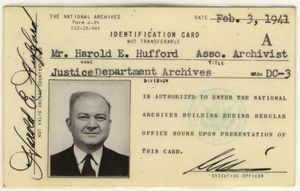

The Senate’s records remained in this state until Secretary of the Senate Edwin P. Thayer, whose term began in 1925, found an original copy of the Monroe Doctrine in the Senate financial clerk's safe. This discovery sparked his interest in preserving additional Senate records that were scattered throughout the basement storerooms of the Capitol. In 1927 Thayer hired Harold E. Hufford, a young George Washington University law student, as a file clerk to find these dispersed and neglected materials and put them in order. Hufford famously recounted going down into the brick-lined rooms of the Capitol basement in search of documents. After cautiously opening a door, disturbing mice and roaches in the process, and walking across the room to turn on a light, he looked down and found a document underfoot; on it was the imprint of his shoe and the signature of Vice President John C. Calhoun. “I knew who Calhoun was,” Hufford said, “and I knew that the nation’s documents shouldn’t be treated like that.” Hufford spent the next six years at the Senate working tirelessly to locate, organize, and index these valuable records, including the first Senate Journal from 1789 and the Senate markup of the Bill of Rights—some of the very same records that Machen and Simpson had saved more than a century earlier.2

Meanwhile, as Hufford labored over the Senate’s neglected documents, construction began on a building to house federal records. Legislation authorizing and funding a national archives had been years in the making, finally culminating in the 1926 Public Buildings Act. The groundbreaking for the National Archives building took place on September 5, 1931, on Pennsylvania Avenue between 7th and 9th Streets Northwest. As one of his last acts as president, Herbert Hoover laid the cornerstone on February 20, 1933.3

Building the National Archives was one thing, but filling it up and running it was quite another. In March 1934 a bill to establish the National Archives as the agency that would manage, preserve, and make available the nation’s federal records was referred to the Senate Committee on the Library, chaired by Tennessee senator Kenneth McKellar. Reporting the bill back to the Senate in May, McKellar called it “one of the most important matters that has been before the Senate for some time.” By June the House and Senate conferees had agreed unanimously on the final report. The bill passed both houses of Congress and on June 19, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Archives Act into law. The legislation created the Office of the Archivist of the United States, with an archivist appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, to oversee all records of the government—legislative, executive, and judicial.4

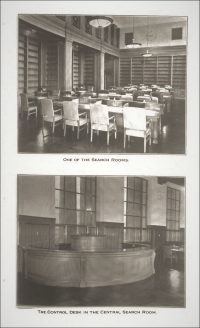

On October 10, 1934, President Roosevelt appointed Robert D. W. Connor as the first archivist of the United States. In his first annual report to Congress, in June of 1935, Connor recalled the many efforts that led to the creation of his office. He noted that while the idea of a “Hall of Records,” which would simply provide a warehouse function, had been circulating through Congress since the early 1800s, it took much longer for scholars and historians to convey to Congress the importance of a national archives in researching and understanding American history. In 1910 the American Historical Association adopted a resolution stating its concern “for the preservation of the records of the National Government as monuments of our national advancement and as material which historians must use in order to ascertain the truth.” The Association petitioned Congress to build a “national archive depository” to properly care for and preserve the records. Connor believed that “the idea of service to Government officials and to scholars as a primary function of a national archives establishment” gave emphasis to “the movement and stimulated a livelier interest in the proposal,” ultimately leading to its success.5

This concept of the National Archives as a place for research and education utilizing our nation’s primary documents has continued, and the Senate participates in those efforts by sending its noncurrent committee and administrative records to the archives—work that began on March 25, 1937, when the Senate authorized the secretary of the Senate to transfer certain records to the custody of the archivist. “From the standpoint of historical as well as intrinsic interest,” remarked the examiner who surveyed the Senate’s collection, “this is perhaps the most valuable collection of records in the entire Government. It touches all phases of governmental activity, and contains a vast amount of research material that has never been used.” Three years earlier, Senate Librarian James D. Preston commented that the imperfect storage of the historic records of the Senate would require their ultimate caretaker to be prepared for a long, hard job and be an expert at document evaluation. Luckily for the Senate, not only did those rescued Senate records move from attics and basements to the newly constructed building, so did Harold Hufford, who left the Senate to join the National Archives staff, becoming director of the legislative section. Hufford didn’t just preserve and catalog Senate records that came to the archives, he also provided excellent service to Senate committees and their staff by loaning back records efficiently and ensuring their safe return to the archives.6

Nearly 50 years later, in an address on Senate history, Senator Robert C. Byrd stated that “many on Capitol Hill said that they could receive faster service on their noncurrent records from the National Archives than they could by keeping and servicing the records themselves.” Senator Byrd’s statement remains accurate today, as staff at the Center for Legislative Archives facilitate the transfer of records to and from the Senate. The Senate archivist in the Senate Historical Office advises senators, committees, and administrative staff on disposition of their noncurrent office files and maintains information detailing locations of former members' papers. Both the Senate Historical Office and the Center for Legislative Archives staff assist students, researchers, scholars, and the general public with reference requests and access to these invaluable historical resources. All of these records, whether housed in gray archive boxes or held electronically on computers, are critical to our ability to research and understand the history of the Senate and our nation.7

Notes

3. See, “A History of the National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.,” National Archives and Records Administration, accessed March 17, 2021, https://www.archives.gov/about/history/building.html.

6. S. Res. 99, Congressional Record, 75th Cong. 1st sess., March 25, 1937, 2735; Frank McAllister to Thomas M. Owen, Jr., February 12, 1937, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; “Senate Librarian Would Make Archives Post Lifetime Job,” Washington Post, September 23, 1934, B7.