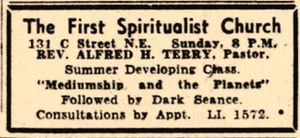

In the early 1950s, Washington D.C.’s “Square 725” was a vibrant city block comprising private residences, organizations, and businesses just blocks to the northeast of the Capitol. Dozens of individuals and families called this place home. Schott’s Alley cut across the heart of Square 725 lined on either side by about 10 residences, some of which were renovated into “deluxe living quarters” by developers in 1954. Locals shopped for groceries at Lucille’s Delicatessen, located at 135 C Street NE. Two doors down at 131 C. Street NE, Rev. Alfred Terry held religious services on Sundays at the First Spiritualist Church and sponsored seances and classes. The Galena and The Merrick, at 132 and 138 B. Street NE respectively, were both lodging homes primarily for women who worked as clerks, stenographers, and typists, many of whom were employed by the Senate. In other words, Square 725 was a lively community much like any other in the District. The U.S. Senate was about to dramatically change it.1

Following World War II, senators sought to modernize their institution, approving the Legislative Reorganization Act in 1946 that provided for the hiring of professional, non-partisan staff. It wasn’t long before the Senate needed additional office space to accommodate that staff. Planning began shortly thereafter to erect a second office building (the first Senate Office Building—today's Russell Senate Office Building—opened in 1909), and the logical location was Square 725. Following the pattern established when the first Senate Office Building had been constructed, the Senate planned to purchase the land and demolish the existing neighborhood to make way for a new structure. By the end of 1949, the Senate had acquired the western half of Square 725, cleared much of the land, and approved a new building design, but construction was delayed. The groundbreaking ceremony for the Senate’s new office building finally took place on January 26, 1955. While waiting on construction, senators discussed acquiring and clearing the entirety of Square 725 for potential building expansion at a later date.

Clearing Square 725, however, would not be so easy. At the corner of Constitution Avenue and 2nd Street NE sat the historic Belmont House, headquarters for the National Woman’s Party (NWP) since 1929. The NWP, one of the most influential American women’s rights organizations of the early 20th century, was credited with helping to secure women’s suffrage and protections from employment discrimination. Belmont House had also been the scene of historic events connected to the Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812. Preservationists considered the structure to be “one of the cornerstones of American heritage on Capitol Hill.”2

The Washington Post reported in early 1956 that the most likely outcome for the entire square was full acquisition by the Senate, potentially by seizure under eminent domain laws, with all structures eventually to be demolished. With legislation for full acquisition pending, the Senate Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds of the Committee on Public Works held hearings in May 1956 to hear from some of the affected parties. Recognizing that the Belmont House was endangered, the NWP rallied in opposition and strongly protested in their testimony.3

During the first moments of the 1956 hearings, Senator Carl Hayden of Arizona, a champion of women’s rights and suffrage even before his Senate service, testified as a witness and offered to amend the pending legislation to exclude the Belmont House, but only if “there should be a quantity of proof before the committee as to the historical value of the property.” In response to Hayden’s offer, nearly a dozen NWP supporters testified to the structure’s unique history, including Augusta Wood Dale, widow of Senator Porter Dale and former Belmont House owner. Most witnesses focused on the house’s age and its connection to early American heritage.4

Dating to about 1800, the house was rented from 1801 to 1813 by Albert Gallatin, secretary of the treasury under President Thomas Jefferson and primary negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty. During the War of 1812, the house gained some notoriety, as conveyed by several witnesses who told the story of shots being fired from the house upon advancing British troops who then burned part of the structure before moving on to burn the Capitol. Several witnesses testified to the historical integrity of the structure and lamented the destruction of historic buildings throughout the District, including the Old Brick Capitol that had been razed to make way for the Supreme Court Building in the 1930s. All throughout the testimony, the building’s connection to the NWP and women’s history was hardly mentioned.5

Despite the testimony at the 1956 hearings demonstrating the historical value of Belmont House, the legislation to acquire Square 725 continued to threaten the house’s existence for the next two years. NWP leader Alice Paul, speaking to the Washington Post, expressed her frustration with the long delay, equating the ongoing threat of demolition to congressional harassment. With full Square 725 acquisition still pending on June 23, 1958, Senator Dennis Chavez of New Mexico, chair of the Committee on Public Works, finally introduced an amendment, penned by Senator Hayden, that excluded seven lots, described as “property in Schott’s Alley and other property,” from the proposed acquisition. In a statement accompanying his amendment, Senator Hayden indicated that he understood acquisition would proceed if “the bill is amended so as to exclude the real property occupied by the NWP.” With the amendment adopted, the bill passed easily. The Senate had spared the Belmont House, for now.6

In 1967, less than 10 years after the opening of the Senate’s second office building (later named the Dirksen Senate Office Building), Senator Jennings Randolph of West Virginia proclaimed that the Senate was “long since past a critical stage” regarding office space. A Committee on Public Works survey concluded that 72 senators and 24 committees required additional space and recommended immediate acquisition of the remainder of Square 725—including portions of the NWP’s property—to build a third office building (later named the Hart Senate Office Building). The Belmont House was again in demolition crosshairs.7

The Senate quietly moved forward with these plans and, unbeknownst to the NWP, passed a bill to acquire the remaining sections of Square 725 by a vote of 42-33 in April 1968. The Senate bill called for condemning two-thirds of the Belmont House property to make way for an access driveway for the newest Senate office building. When the House considered the bill that September, NWP leadership finally learned of the plan and rushed to make their voices heard. NWP leaders fired off telegrams, visited House of Representative offices, and spoke directly to the media over the course of about two weeks as the bill neared House approval. Joining the NWP in its crusade to save Belmont House was “a new coalition of college girls and radicals,” according to the Washington Post, including the newly created National Organization of Women and members of the National Women’s Liberation Group. The house’s connection to women’s history was now front and center. To the relief of NWP leadership, the House rejected the legislation, and the Belmont House was spared for a second time.8

The Belmont House’s future brightened significantly between 1972 and 1974. First, Congress authorized the purchase of some of the NWP’s peripheral property, providing funds for the organization to discharge its debts. Next, the National Capital Planning Commission worked with the National Park Service (NPS) to have the house listed on the National Register of Historical Places, thus formally recognizing the structure’s national historical significance for the first time. Writing in support of the listing, an unsigned NPS commenter noted, “They’ve torn down all adjacent housing and I’m sure that they’ve got this in mind next.” The Belmont House also benefitted from increased attention to women’s rights. In 1972 the Senate overwhelmingly approved the Equal Rights Amendment, to prohibit discrimination on account of sex, by a vote of 84-8. The House had already passed the bill, and it was sent to the states for ratification.9

In 1974 a Senate staff member kickstarted legislation to permanently save the Belmont House. Then-NWP National Chairman Elizabeth Chittick approached Frankie Sue Del Papa, a law student in her third year working as a staff member in the office of Senator Alan Bible of Nevada. Del Papa created a law school project, with the blessing of Senator Bible, to draft legislation that would, in her words, “save the Sewall-Belmont House from eminent domain.” Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington introduced the legislation on March 19, 1974, and called for its passage because “the women’s rights movement is not itself represented” within the National Park Service. Senator Bible wholly supported the bill and, as chairman of the Subcommittee on Parks and Recreation of the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, scheduled hearings for May 31, 1974.10

Many senators testified at the subcommittee hearing in favor of permanently protecting the Belmont House because of its connections to women’s history. Senator Jackson provided the context and impetus for such action: “What a fitting statement by Congress to create a women’s history monument as the Equal Rights Amendment marched towards certain ratification.” Senator Howard Metzenbaum of Ohio, who co-sponsored the bill, echoed this sentiment while also drawing a metaphor about the women’s rights movement and the Belmont House itself: “In this house, much of the history of the woman's movement was made, fragile gains cementing one another, somewhat as the brick walls of the kitchen were laid with mortar made from oyster shells.” Del Papa’s testimony underscored the importance of the Belmont house as a symbol of women’s history. “Previous Senate committees have not always been so thoughtful of this neighboring historic house,” she explained, reminding senators the house was nearly razed in the 1950s, before praising “some farsighted Senators [who] sought to preserve for posterity this symbol of, and monument to, the women’s rights movement.”11

On October 4, 1974, a favorable report from Senator Bible of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs recommended passage of an NPS omnibus bill creating six park units, amended to include the “Sewall-Belmont House National Historical Site” as a “cooperative agreement to assist in the preservation and interpretation of such house.” Four days later, the Senate passed the measure without debate, and it was signed into law by President Gerald Ford later that month. According to Del Papa, significant support in the Senate came from Senator Bible’s direct appeal to other members. 12

Today the Belmont House stands proudly at the corner of 2nd Street NE and Constitution Avenue—the only remaining structure of the once vibrant Square 725. Sitting at the Capitol’s periphery since 1800, the Belmont House was associated with historically significant events and people, but it was its connection to the women’s suffrage movement that ultimately saved it from the wrecking ball. According to Elizabeth Chittick, the Belmont House is “a place where women may find their identity with the history of the past in their march for equal rights.” Senator Jackson brought this same sentiment to the Senate floor in 1974, stating the Belmont House represented “contributions and efforts which women have made to the development of this nation and in awakening social conscience for human rights.” This perspective took years to form within the Senate, but largely thanks to efforts by the NWP and senators who listened, the Belmont House became central to American history and heritage at a particularly significant time for the advancement of women’s rights. Today, under the protections of the National Park Service, the Belmont House, now the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, serves as a reminder of that powerful political heritage. 13

Notes

1. Senate Committee on Public Works, Extension of Capitol Grounds: Hearings on S.3704, 84th Cong., 2nd sess., May 21–22, 1956 (hereafter referred to as “1956 Hearings”), 9; Population Schedule for Washington D.C., ED 1-785, Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950, Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; “Rooms Furnished-N.E.,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), August 15, 1950.

2. Note that the “Belmont House” has been known by many names over the years. As of 2025, it is formally known as the “Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument.” It has also been known as the Sewall House (1800–1929), the Alva Belmont House (1929–1972), and the Sewall-Belmont House and Museum (1972–2016). This essay refers to the structure as the “Belmont House” for simplicity and because this was the terminology typically used by senators from the 1940s through the 1970s; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, Hearing held before Subcommittee on Fiscal Affairs of the Committee on the District of Columbia, S.2306, Relating to the Exemption of the National Woman’s Party, Inc. from Taxation in D.C., 86th Cong., 2nd sess., January 19, 1960 (hereafter referred to as “1960 Hearing”), 14–19.

3. “Senate Unit Votes $4.5 million to Buy 1 1/2 Blocks Near ‘Hill’ Area,” Washington Post and Times Herald, February 9, 1956; 1960 Hearing, 25; Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia, S. Rep. 57-166, 57th Cong., 1st sess., 1902, 37–40; Quinn Evans, Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument: Historic Resource Study, National Park Service (Jan. 2021): 3–51; Enlarging of the Capitol Grounds: The Final Report of the Commission for Enlarging of the Capitol Grounds, S.Doc 76-251, 76th Cong., 3rd sess., 1943, 493.

6. Paul Sampson, “New Belmont House War,” Washington Post and Times Herald, February 19, 1957; Richard L. Lyons, “Belmont House Women in Arms,” Washington Post and Times Herald, March 29, 1957; “$965,000 Voted in Parking Bill,” Washington Post and Times Herald, January 30, 1958; Congressional Record, 85th Cong., 2nd sess., July 17, 1958, 11943.

8. Emma Guffey Miller and Alice Paul to Senator Everett Jordan, September 17, 1969; Emma Guffey Miller and Alice Paul to Hale Boggs, September 17, 1968; Emma Guffey Miller to John W. McCormach, September 24, 1968; Mary Birckhead and Alice Paul to Charles E. Bennett, September 26, 1968; Alice Paul to Emma Guffey Miller, September 26, 1968, NWP Papers, Part 1, Section C: 1945–1974 (Sep. 1 – Sep. 30, 1968); "An Act to Authorize the Extension of the Additional Senate Office Building Site,” S.2484 90th Cong., 2nd sess., 1967; “Senate Office Building,” CQ Almanac 1968 24 (1969); ”One House Saves Another,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1968; ”Delay in Belmont House Bill,” Los Angeles Times, September 24, 1968; ”Senate Plan Brings Ringing Protests,” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1968.

10. “Frankie Sue Del Papa,” Nevada Women’s History Project, accessed March 14, 2025, https://nevadawomen.org/del-papa-frankie-sue/.

12. An Act to provide for the establishment of the Clara Barton National Historic Site, Maryland; John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon; Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota; Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Massachusetts; Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama; and Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, New York; and for other purposes, Public Law 93-486, 93rd Cong., 2nd. Sess., October 26, 1974, 88 Stat. 1463; Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Report on Providing for the Establishment of Clara Barton National Historic Site, Md., and Other Historic Sites and Memorials, S. Rep. 93-1233, 93rd Cong., 2nd. sess., October 4, 1974; Senate Committee on Public Works, Addition to the Dirksen Senate Office Building, Hearing, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., 1974, 49; Congressional Record, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., October 8, 1974, 34297–401; Wauhillau LaHay, “She’s the Happiest Woman in Washington,” NWP Papers, Group II: Printed Matter, 1850–1974.