| 202502 26Reconstruction Louisiana and the Case of PBS Pinchback

February 26, 2025

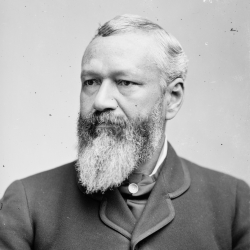

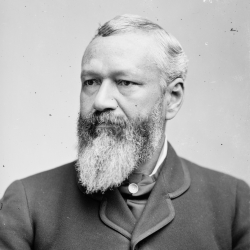

In February 1870, Hiram Revels of Mississippi made history as the first Black American to be elected to the United States Senate. Revels served only 13 months, but five years later the Mississippi legislature, still under the control of Republicans who were swept into office as part of post-Civil War Reconstruction, elected Blanche K. Bruce, making him the first Black American elected to a full Senate term. Often forgotten, however, is another pioneering Black politician, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback of Louisiana, who was elected to the Senate in 1873 but never allowed to take his seat.

In February 1870, Hiram Revels of Mississippi made history as the first Black American to be elected to the United States Senate. Revels served only 13 months, but five years later the Mississippi legislature, still under the control of Republicans who were swept into office as part of post-Civil War Reconstruction, elected Blanche K. Bruce, making him the first Black American elected to a full Senate term. Often forgotten, however, is another pioneering Black politician, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback of Louisiana, who was elected to the Senate in 1873 but never allowed to take his seat.

Pinchback’s story offers a window into an era of political upheaval in the United States, when Black Americans fought to exercise their newly won political and civil rights in the South, and former Confederates sought, often violently, to reclaim power from Republican-dominated Reconstruction governments in which a large number of African Americans held office. Throughout the 1870s, members of the Senate and House of Representatives debated the power of Congress to ensure fair elections in the South and enforce protections enshrined in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.1

Pinchback, who went by the initials PBS but was “Pinch” to his friends, was born in 1837 to a formerly enslaved mother, Eliza Stewart, and her white enslaver, Major William Pinchback. Major Pinchback had freed and married Stewart and moved the family to Mississippi. When Major Pinchback died in 1848, Stewart, denied the Pinchback estate by Mississippi courts and fearing re-enslavement by Major Pinchback's family, moved with her children to Cincinnati, Ohio, where PBS Pinchback was already attending boarding school. At 12 years old, Pinchback ended his formal education and went to work on Mississippi river boats, eventually falling in with a gambler who instructed him in the art of dice and card games.2

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Pinchback made his way to Union-occupied New Orleans where he enlisted with the Union army. He was tasked by General Benjamin Butler with recruiting a company of Black soldiers and was commissioned as the company’s captain. He resigned in September 1863 after enduring poor treatment from white troops and officers. A gifted orator, Pinchback went north after the war to promote Black suffrage in the South and later settled in Alabama to help freedmen organize for their political rights.3

After the Radical Republicans in Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act in 1867 to remove former Confederates from power and protect Black rights, Pinchback returned to New Orleans to work with Republican officials in the city. A speech he delivered at the Republican state party convention in defense of Black civil rights led to Pinchback’s appointment to the party’s executive committee, followed by his election to the state constitutional convention in 1867. When the constitutional convention first met in 1866, a white mob had disrupted the proceedings and sparked what came to be known as the Mechanics Institute Massacre (the Institute was being used as the State House at the time), which left 46 African Americans dead and another 60 injured. At the 1867 constitutional convention, undeterred by the threat of violence, Pinchback led the drafting of a civil rights article for the new constitution that granted Blacks the right to vote and disenfranchised former Confederates.4

Impressed with his performance at the convention, Louisiana Republicans floated Pinchback as the party’s nominee for governor, but he demurred and supported a young white attorney from Illinois, Henry Clay Warmoth, who won election in April 1868 along with other Radical Republicans, despite widespread violence and intimidation against Black voters. Meanwhile, Pinchback won election to the state senate, but only after a state committee on elections determined there had been fraud in the balloting and awarded him the seat.5

In the years that followed, Republicans in Louisiana and Washington split into contending factions over the future of Reconstruction, forcing Pinchback to negotiate a rapidly shifting political landscape. The state’s Black Republicans grew frustrated with Governor Warmoth as he failed to support strong civil rights legislation and curried favor with white Democrats by, among other things, appointing former Confederates to state office. Pinchback initially continued to support Warmoth and was rewarded with election as president of the Senate, a post that carried with it duties as acting lieutenant governor. But in 1872, when Warmoth announced his support for presidential candidate Horace Greeley, a Democrat backed by the new Liberal Republican Party who came to oppose Radical Reconstruction in favor of reconciliation with former Confederates, Pinchback broke with his political patron. Back in the good graces of the state’s regular Republicans, Pinchback campaigned for President Ulysses S. Grant and for continued federal support for Black civil rights in the South. In the race for Louisiana governor, Pinchback stumped for U.S. Senator William Pitt Kellogg against Democrat John McEnery, who ran with the support of Warmoth and the state’s Liberal Republicans.6

The 1872 elections left Louisiana in political chaos. McEnery and his coalition of Democrats and Liberal Republicans declared themselves the victors, while the state’s Republicans charged that they would have won if not for widespread fraud and violence against Black voters. When Governor Warmoth took control of the state’s election board to certify the Democratic victory in violation of a federal court order, the district judge intervened, and federal troops took control of the State House. On December 9, 1872, the Republicans passed articles of impeachment against Warmoth, which under Louisiana law suspended him from office pending trial. As a result, Pinchback became the acting governor, the first Black governor of a state in the nation’s history. When the newly elected government was to meet on January 14, both sides organized rival governments, each claiming to be the legitimate representatives of the people. Backed by the federal courts, the Republicans gathered in the State House and inaugurated Kellogg as governor, while the Democrats organized their own legislature at City Hall and swore in McEnery.7

Louisiana’s political troubles soon reached the U.S. Senate, with Pinchback at the center. When Kellogg resigned his Senate seat to take over as governor, the competing legislatures each elected a replacement to complete the final weeks of Kellogg’s term. Both Democrat William McMillen and Republican John Ray presented their credentials—one signed by McEnery and the other by Kellogg, respectively—to the Senate. At the same time, the Republican legislature elected Pinchback to the Senate for the full term beginning on March 4, 1873, and the Democratic coalition legislature elected McMillen for the seat.

A Senate increasingly divided over Reconstruction policies and the role of the federal government in enforcing Black political rights in the South took up the question of who held rightful claim to Louisiana’s Senate seat. The Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, chaired by Radical Republican leader Oliver Morton of Indiana, launched an investigation into “whether there is any existing State government in Louisiana” that could name a senator. After a month of examination, the committee recommended rejecting both sets of credentials and offered a bill to mandate new elections in the state. A committee majority—which included Republicans Matthew Carpenter of Wisconsin, John Logan of Illinois, James Alcorn of Mississippi, and Henry Anthony of Rhode Island—concluded that if the election had “been fairly conducted and returned, Kellogg … and a legislature composed of the same political party, would have been elected,” and that recognizing the McEnery government without scrutinizing the election returns “would be recognizing a government based upon fraud, in defiance of the wishes and intention of the voters of that State.” But the majority also charged that the Republican legislature in Louisiana had no legal authority, strongly condemned the intervention of the federal courts, and concluded that the Republicans had “usurped” the government by tossing out the Democratic victory. In the minority, Democrats on the committee called for McMillen to be seated, arguing that Congress had no role to play in state elections and could not throw out the Democrats’ “official” results. Only Chairman Morton made the case that the Republicans were entitled to the seat unconditionally. The full Senate took no action, however, and the seat remained vacant.8

When new senators were sworn in at the start of the 43rd Congress on March 4, 1873, the Senate did not address the Louisiana seat. That spring, white paramilitary groups continued a campaign of violence against Black Louisianans, including the infamous Colfax Massacre in April when 80 to 100 African Americans were killed. Despite the ongoing political violence, a growing number of senators began to question federal intervention in the South. When the Senate convened for the first regular session in December 1873, the Committee on Privileges and Elections took up Pinchback’s case but reported that they were “evenly divided” and “beg[ed] leave to be discharged from further consideration.” Pinchback faced yet another setback in January 1874 when his champion in the Senate, Oliver Morton, heard rumors that Pinchback had secured his election through bribes and wavered in his commitment to the case. When Morton moved for a new investigation into Pinchback’s personal conduct by the Committee on Privileges and Elections, Matthew Carpenter instead introduced a resolution calling for new elections in Louisiana. Neither resolution was put to a vote, the case languished for the remainder of 1874, and the seat remained vacant.9

Pinchback’s case received new life in January 1875 when, after another contested election in 1874, Louisiana’s Republican legislature again elected him to the Senate “in order that all doubts or questioning of the title … be entirely silenced.” Morton set his qualms aside and threw himself once again behind securing Pinchback his seat. Senate Democrats refused to concede the fight and launched a filibuster that kept the Senate in session all night on February 17. They had the support of a number of Republicans, such as George Edmunds of Vermont, who had become highly critical of Reconstruction policy and the federal government’s role in supporting Black voters in the South. The debate continued on and off for weeks, with Republicans railing against the frauds and intimidation that had allowed McEnery and the Democrats to claim victory in the 1872 elections, and Democrats dismissing Kellogg as a “usurper.” By the end of the session, Republicans had still failed to get a vote on the Pinchback resolution.10

Meanwhile, in December 1874, responding to a plea from President Grant, the House of Representatives had created a committee to investigate Louisiana’s 1874 elections and resolve the political deadlock. New York Representative and future Vice President William Wheeler produced a plan, later known as the Wheeler Compromise, whereby the Democrats would accept Kellogg’s position as governor and be granted a majority of seats in the state assembly, and the Republicans would be given control of the state senate. Kellogg and both parties accepted the plan in April 1875, and in January 1876 this newly constituted Louisiana legislature declared the Senate seat vacant and elected a new senator, James B. Eustis, a Democrat. A trio of Republican Louisiana state senators submitted a statement to the Senate lamenting “being unable … to elect a gentleman strictly of our own party faith” but defending Eustis’s election as “an act in the interests of peace and prosperity, and a healthy and lasting good-will among all here at home.” This willingness by Republicans to compromise at the expense of Black voters signaled the beginning of the end of Reconstruction in Louisiana.11

Morton refused to accept that the Louisiana seat was vacant for Eustis to claim and in February 1876 put Pinchback’s case before the Senate one last time. Blanche Bruce of Mississippi, who had entered the Senate the previous year, used the occasion to deliver his maiden speech. Bruce told his Republican colleagues that to reject Pinchback amounted to the federal government turning its back on Louisiana and its Black citizens. In a closed executive session, Bruce was even more forceful. “If when the Louisiana case is again called, it be not settled,” he stated, “I will resign my seat in a body which presents this spectacle of asinine conduct.”12

The Senate did settle the case, and Bruce did not resign. On March 8, 1876, more than three years after Pinchback had arrived in Washington to take the oath of office, the Senate rejected his claim to the seat. Seated at the back of the Chamber while the final debate and vote took place, Pinchback reportedly “acted as one relieved, and who felt the great strain was over.” As a consolation, the Senate awarded him $16,000, approximately what he would have earned as a senator during those three years.13

Pinchback returned to New Orleans where he remained an important political figure for a time, even as Democratic lawmakers consolidated their power in the former Confederate states under Jim Crow laws. In a letter to Blanche Bruce, he called himself “the liveliest corpse in the dead South.” Pinchback settled back in Washington in the 1890s and remained a presence at banquets and parties but increasingly seemed a relic of a bygone political era, when Black southerners had won election to federal office. Pinchback died in 1921 at the age of 84. After Blanche K. Bruce left the Senate in 1881, more than 80 years passed before another African American—Edward Brooke of Massachusetts—won election to the Senate.14

Notes

1. History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, Office of the Historian, Black Americans in Congress, 1870–2007, “’The Fifteenth Amendment in Flesh and Blood:’ 1870–1901,” accessed February 18, 2025, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Essays/Fifteenth-Amendment/Introduction/.

2. Philip Dray, Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction Through the Lives of the First Black Congressmen (Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 103; George H. Devol, Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi, (Home Book Co., 1894), 216–17.

3. Charles Vincent, Black Legislators in Louisiana During Reconstruction (Southern Illinois University Press, 2011), 8–10; James Haskins, The First Black Governor: Pinkney Benton Stewart Pinchback (MacMillan, 1973; African World Press, 1996), 24–25, 38–45.

4. Haskins, First Black Governor, 47–54, 56–60; Dray, Capitol Men, 28–32, 106.

5. Dray, Capitol Men, 107.

6. Dray, Capitol Men, 109–110, 117–118, 124–127; Haskins, First Black Governor, 82–83, 100–102; “New Orleans,” New York Times, January 21, 1872, 1.

7. Dray, Capitol Men, 134. For the most complete details of the events surrounding the elections, see Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Louisiana Investigation, S. Rpt. 457, 42nd Cong., 3rd sess., February 20, 1873.

8. S. Rpt. 457, XLIV.

9. Congressional Record, 43rd Cong., 1st sess., December 15, 1873, 188; January 30, 1874, 1036–58; March 3, 1874, 1926–27; Haskins, First Black Governor, 196–99, 202–4; Dray, Capitol Men, 224–25. In the meantime, Pinchback had been on the ballot for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1872, but the election was contested and remained unresolved for much of the 43rd Congress. He pleaded his case to the House of Representatives in June 1874 to obtain the at-large seat, but the House awarded the seat to his Democratic opponent.

10. “In Louisiana,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 13, 1875, 1; Resolution that Senate recognize validity of credentials of P. B. S. Pinchback, S. Mis. Doc. 16, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., December 23, 1874; Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Credentials of P. B. S. Pinchback, for seat in Senate from Louisiana, S. Rpt. 626, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., February 8, 1875.

11. James T. Otten, “The Wheeler Adjustment in Louisiana: National Republicans Begin to Reappraise Their Reconstruction Policy,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 13, no. 4 (1972): 349–67; Views of certain State senators on election of Hon. J. B. Eustis as United States Senator from Louisiana, S. Mis. Doc. 41, 44th Cong, 1st sess., January 26, 1876.

12. New Orleans Times, February 17, 1876, quoted in Sadie Daniel St. Clair, The National Career of Blanche Kelso Bruce (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1947), 96–97.

13. Congressional Record, 44th Cong., 1st sess., March 8, 1876, 1557–58; New Orleans Republican, March 14, 1876, quoted in Haskins, 221; Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, Question of allowance proper to be made to P. B. S. Pinchback, late contestant for seat in Senate from Louisiana, S. Rpt. 274, 44th Cong., 1st sess., April 17, 1876.

14. Haskins, First Black Governor, 241; “Pinchback, Louisiana Governor in 1872, Dead,” Washington Post, December 22, 1921, 10.

|

| 202201 03Three Brothers Compete for One Senate Seat

January 03, 2022

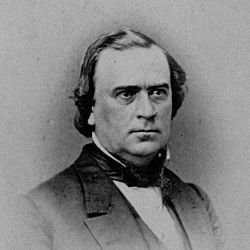

The 1871 election of a U.S. senator from Delaware remains unique in Senate history. That year, Senator Willard Saulsbury, Sr., of Delaware sought reelection to a seat he had occupied since 1859. With two Senate terms behind him, Saulsbury was quite confident that he could gain a majority vote in the Delaware state legislature to win reelection, but two surprising competitors challenged him for the seat—his brothers.

The 1871 election of a U.S. senator from Delaware remains unique in Senate history. That year, Senator Willard Saulsbury, Sr., of Delaware sought reelection to a seat he had occupied since 1859. With two Senate terms behind him, Saulsbury was quite confident that he could easily gain the 16-vote majority he needed from the 30-member state legislature, but—to his surprise—two serious competitors challenged him for the seat.

Willard Saulsbury began his Senate career in 1859 as a “copperhead” (or “peace Democrat”), someone who resisted secession and opposed war while maintaining opposition to the abolition of slavery. Believing that the Union could be saved through peaceful means, he proposed a “Central Confederacy” of states that excluded the extreme proslavery states of the South as well as the radical antislavery states of the North. His proposal was ignored.1

Soon after taking office, Saulsbury began having “political difficulties,” often due to a combination of his combustible personality and his fondness for alcohol. In 1863, for example, as the Senate debated a bill to criticize President Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, Saulsbury accused Lincoln of being a “weak and imbecile” man. “If I wanted to paint a despot,” he proclaimed, “I would paint the hideous form of Abraham Lincoln.” Vice President Hannibal Hamlin called Saulsbury out of order and demanded that he take his seat, but the Delaware senator refused. When Hamlin directed the sergeant at arms to “take the senator in charge,” Saulsbury drew a pistol. “Let him do so at his expense,” he cried and threatened to shoot the officer. Days later, facing a resolution of expulsion, Saulsbury apologized. The Senate considered expelling him again in 1867 when he repeatedly appeared in the Chamber intoxicated, but Saulsbury managed to escape disciplinary action.2

Not surprisingly, by 1871 members of the Delaware state legislature had grown concerned about Saulsbury’s erratic behavior. As his reelection drew near, party leaders discretely approached another possible candidate—the senator’s elder brother, Gove Saulsbury. A physician and out-going governor of Delaware, the ambitious Gove readily agreed to challenge his younger brother. Willard cried foul and charged Gove with betrayal, vowing to stop at nothing to defeat him. Thus the two brothers—Willard and Gove—became fierce competitors for the Senate seat. As if that wasn’t complicated enough, when state legislators prepared to vote on January 17, 1871, a third, surprise candidate appeared—Eli Saulsbury, the third brother. Three brothers—one Senate seat.

On the first two ballots, the incumbent Willard drew 13 votes, but Gove got 14 with Eli trailing far behind. On the third ballot, Gove held the lead with 15, followed by Willard at 14, leaving just a single vote for Eli. As the fourth ballot began, knowing that Gove was just one vote away from a majority, a bitter Willard released his supporters and backed brother Eli as a compromise candidate. Eli Saulsbury won the election.3

Unlike his very competitive brothers, Eli was not a fiery orator nor a partisan crusader. “He was a quiet plodder,” suggested a reporter, “a lawyer by profession, and a man who was plain and unassuming.” He was also a dedicated teetotaler. Eli Saulsbury remained in office for the next 18 years.

Notes

1. American National Biography, s.v. “Saulsbury, Willard (02 June 1820–06 April 1892)”; Harold B. Hancock, Delaware During the Civil War: A Political History (Wilmington: Historical Society of Delaware, 1961).

2. Richard A. Baker, 200 Notable Days: Senate Stories, 1787 to 2002 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2006), 77; Hancock, Delaware During the Civil War, 129; Jonathan W. White, Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011), 72; Mark Scroggins, Hannibal: The Life of Abraham Lincoln’s First Vice President (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1994), 195; Congressional Globe, 37th Cong., 3rd sess., January 27, 1863, 549–84; Robert C. Byrd, The Senate, 1789–1989: Addresses on the History of the United States Senate, vol. 2, ed. Wendy Wolff, S. Doc. 100-20, 100th Cong., 1st sess. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1991), 98–100.

3. “Hon. Eli Saulsbury, the New Senator from Delaware,” New York Times, January 20, 1871, 2; “Washington: The Closing Scenes of Congress,” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1871, 2; “United States Senators Elect: Eli Saulsbury, of Delaware,” Baltimore Sun, January 19, 1871, 1; “Political,” Chicago Tribune, January 26, 1871, 3.

|