Each year, before a joint session of Congress, the president fulfills his or her constitutional duty to "from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient." The ceremony that we know today as the State of the Union Address follows well established protocols and rituals, but it has evolved a great deal since 1790, when President George Washington delivered his first annual address to Congress. One aspect in particular—the opposition response—is a modern practice that has developed to address a problem faced by Congress in its earliest years.1

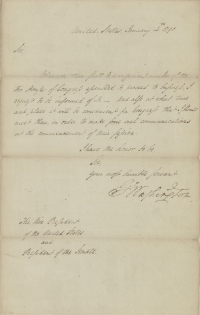

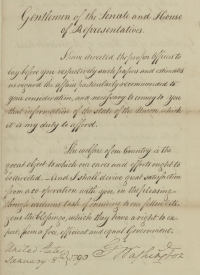

In January 1790, as members of both the House and Senate gathered to begin the second session of the First Congress, President Washington wrote to John Adams (who as vice president also served as president of the Senate) that he wished to address both houses in a joint session as soon as they reached a quorum. The two houses achieved quorums on January 7 and informed the president they were ready to receive his message. On January 8, the president arrived at Federal Hall at 11:00 a.m. and proceeded to the Senate Chamber, where, accompanied by a few of his personal aides, he delivered his address to senators, representatives, and cabinet members. In his brief speech, Washington congratulated Congress on the “present favorable prospects of our public affairs,” highlighted the progress of the young nation, and made policy suggestions, including calling for the establishment of a national militia and a uniform system of currency.2

After Washington departed Federal Hall and representatives returned to their chamber, the Senate appointed a committee “to prepare and report the draft of an Address to the President of the United States, in answer to his Speech delivered this day to both Houses of Congress, in the Senate Chamber.” In keeping with the traditional ceremonial exchange between British Parliament and the King, both the Senate and House had offered a formal response to the president’s first inaugural address in April 1789, and both chambers prepared to follow that same practice with Washington’s annual message. Not all senators agreed, however, as to how the Senate should respond to the president’s speech. According to Pennsylvania senator William Maclay, South Carolina senator Pierce Butler thought that “the Speech was committed rather too hastily” and “made some remarks on it.” When Vice President Adams called Butler to order for his criticism, Maclay wrote that Butler “resented the call, and some Altercation ensued.”3

A few days later, the committee presented a draft response to the Senate, which assured the president that the Senate would address each issue that he mentioned, point by point. Maclay, who was becoming a staunch opponent of the Washington administration, objected to the response. He called it “the most Servile Echo” he ever heard, and while the Senate did amend some sections of the original draft, Maclay complained that many clauses were passed without roll-call votes, leaving opponents to accept them “in silent disapprobation.” Meanwhile, the House of Representatives followed the same procedure, meeting to collaborate on a response, a process that proved both “time-consuming and contentious.” Once the House and Senate finally approved their drafts, each body then agreed to wait on the president en masse at his residence to present their responses in person. Following these formal presentations, the president then delivered his own responses.4

The ceremonial spectacle of these proceedings struck some members as obsequious and unnecessary, including Maclay, who worried that the response could be considered by the president’s administration as a tacit approval of its policies. “It was a Stale ministerial Trick in Britain, to get the Houses of parliament to chime in with the speech, and then consider them as pledged to support any Measure which could be grafted on the Speech.” A foreign observer who witnessed both the president’s speech and Congress’s responses noted that the exchange “looked completely like that practiced in England between the King and Parliament” except for the fact that “the next day not one voice was raised in the two Houses to attack any part whatever of the address.” The opposition remained silent.5

As partisan factions developed during Washington’s administration, the process of drafting and agreeing to a single institutional response became impractical. Washington interpreted the Constitution’s directive “from time to time” to mean once a year, and every president since Washington has followed this precedent. This meant that year after year, both the Senate and House spent days, and sometimes weeks, during Washington’s presidency tediously debating their respective responses paragraph by paragraph, arguing over word choice and overall tone. In addition, those in the Senate minority remained frustrated with Senate responses that supported administration policies and ignored dissenting views.

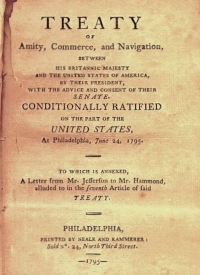

In December 1795 Washington delivered his annual address at the first session of the Fourth Congress, six months after the Senate had convened in a special executive session to consider the controversial Jay Treaty. The Senate’s rancorous debate over the treaty had deepened the partisan divisions among senators, with the majority pro-administration Federalists supporting it and anti-administration Democratic Republicans voting in opposition. The Senate approved the treaty for ratification by the slimmest margin. In his speech, Washington referred to the treaty, declaring that the “summary of our affairs, with regard to the Foreign powers between whom and the United States controversies have subsisted . . . opens a wide field for consoling and gratifying reflections.”6

The treaty’s opponents felt neither consoled nor gratified. When the draft of the Senate’s response included similar praise for the treaty, the Democratic-Republicans objected. Virginia senator Stevens Thomson Mason argued that referring to the treaty in this way served only to rekindle animosities among senators. “The minority on that occasion were not now to be expected to recede from the opinions they held then, and they could not therefore join in the indirect self-approbation which the majority appeared to wish for.”7

Virginia senator Henry Tazewell not only objected to the passage about the treaty, but he questioned the practice of a congressional response altogether, asking “what had given rise to the practice of returning an answer of any kind to the President’s communication to Congress in the form of an Address? There was nothing . . . in the Constitution, or in any of the fundamental rules of the Federal Government which required that ceremony from either branch of the Congress.” Tazewell’s observation was true, but many in Congress clung tight to the pageantry and ceremonial trappings of the executive-legislative exchange.8

Despite the protests of the Democratic-Republicans, attempts to remove the offending passages from the Senate’s response failed. The Senate then approved what was essentially the majority’s response to the annual address on a party-line vote of 14-8. While responses to Washington’s remaining annual addresses and those of John Adams do not appear to have been debated quite as intensely, the strong Federalist majorities in the Senate of that era meant that the minority voice remained unheard.9

_1800_capitol_wing_l.jpg)

When Congress moved from Philadelphia to the newly created capital city of Washington in the District of Columbia in 1800, the tradition of the executive-legislative exchange continued. President Adams presented his final annual address to Congress in person at the Capitol, and both the Senate and House presented responses to the president at his new residence. Unlike Philadelphia, however, where Congress Hall was a mere block from the president’s residence, in the District of Columbia the President’s House was more than a mile from the Capitol, making the trip less convenient. This was one of the reasons given by President Thomas Jefferson in 1801 when he chose to send his message to Congress in writing. He further suggested that the Senate and House need not prepare their official replies:

The circumstances under which we find ourselves at this place rendering inconvenient the mode heretofore practiced, of making by personal address the first communications between the legislative and executive branches, I have adopted that by message, as used on all subsequent occasions through the session. In doing this I have had principal regard to the convenience of the legislature, to the economy of their time, to their relief from the embarrassment of immediate answers, on subjects not yet fully before them, and to the benefits thence resulting to the public affairs.10

For the rest of the 19th century, and into the 20th, presidents followed Jefferson’s example, and Congress stopped officially replying to the president. The annual message to Congress became a lengthy report that laid out the activities and financial needs of the executive branch and included policy recommendations and a summary of foreign affairs. This was the case until 1913, when Woodrow Wilson announced that he would read his annual address to Congress in person.

Wilson understood the power of public opinion in pressuring Congress to support his agenda, so he tailored his speech to appeal to a much wider audience—the American public. He kept the address short but visionary, hoping to persuade and move his audience through emotional rhetoric. According to press reports, Wilson’s in-person performance was a “triumph.” His successors continued the tradition of in-person delivery, and the State of the Union Address became a platform that elevated the priorities of the president and his party. Even more so than during the nation’s founding era, members of the opposing political party found themselves without a formal role to play in the annual event. The advent of television in the 1940s and ʼ50s and the shift of the speech delivery from daytime to prime time in 1965 further expanded the reach of the president’s message, prompting minority leadership in Congress to finally develop a coordinated response. In 1966 Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen and House Minority Leader Gerald Ford recorded a 30-minute rebuttal which aired on major television networks a week after the president’s speech. The opposition response was born.11

Today, the opposition response is broadcast live immediately following the president’s speech. It has become an integral part of this annual ritual, anticipated and discussed almost as much as the address itself—thanks in part to social media platforms. No doubt the Democratic-Republicans of the early 19th century would have appreciated this innovation. What began in the Senate and House as congressional responses expressing the approbation of the president’s majority party has evolved into an opposition response by the other national party, reflecting the complexity of both party politics and executive-legislative relations and demonstrating the delicate balance of power between discordant forces in our system of government.

Notes

3. Ibid., 104; Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., 20, 22–23, 26–27; Kenneth R. Bowling and Helen E. Veit, eds., Diary of William Maclay and Other Notes on Senate Debates, vol. 9 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 180.

4. Bowling and Veit, Diary of William Maclay, 181; “A ‘Troublesome and Greatly Derided Custom’ — Answering the Annual Message,” History, Art, & Archives, United States House of Representatives, Whereas: Stories from the People’s House, https://history.house.gov/Blog/2016/January/1-12-LyonResponse/, accessed January 19, 2024.

5. Bowling and Veit, Diary of William Maclay, 181; Letter from Louis Guillaume Otto to Comte de Montmorin, January 12, 1790, in Charlene Bangs Bickford, Kenneth R. Bowling, Helen E. Veit, and William Charles diGiacomantonio, eds., Correspondence, Second Session: October 1789–14 March 1790, vol. 18 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 196–97.