| 202401 31The Evolution of the Response to the State of the Union

January 31, 2024

Each year, before a joint session of Congress, the president fulfills his or her constitutional duty to "from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient." Today’s State of the Union Address follows well established protocols and rituals, but one aspect in particular—the opposition response—is a modern practice that has evolved to address a problem faced by Congress in its earliest years.

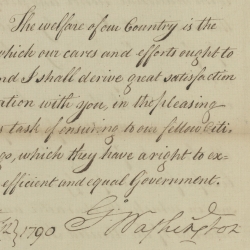

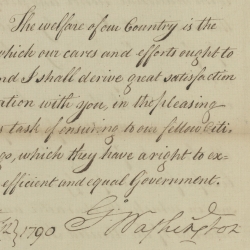

Each year, before a joint session of Congress, the president fulfills his or her constitutional duty to "from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient." The ceremony that we know today as the State of the Union Address follows well established protocols and rituals, but it has evolved a great deal since 1790, when President George Washington delivered his first annual address to Congress. One aspect in particular—the opposition response—is a modern practice that has developed to address a problem faced by Congress in its earliest years.1

In January 1790, as members of both the House and Senate gathered to begin the second session of the First Congress, President Washington wrote to John Adams (who as vice president also served as president of the Senate) that he wished to address both houses in a joint session as soon as they reached a quorum. The two houses achieved quorums on January 7 and informed the president they were ready to receive his message. On January 8, the president arrived at Federal Hall at 11:00 a.m. and proceeded to the Senate Chamber, where, accompanied by a few of his personal aides, he delivered his address to senators, representatives, and cabinet members. In his brief speech, Washington congratulated Congress on the “present favorable prospects of our public affairs,” highlighted the progress of the young nation, and made policy suggestions, including calling for the establishment of a national militia and a uniform system of currency.2

After Washington departed Federal Hall and representatives returned to their chamber, the Senate appointed a committee “to prepare and report the draft of an Address to the President of the United States, in answer to his Speech delivered this day to both Houses of Congress, in the Senate Chamber.” In keeping with the traditional ceremonial exchange between British Parliament and the King, both the Senate and House had offered a formal response to the president’s first inaugural address in April 1789, and both chambers prepared to follow that same practice with Washington’s annual message. Not all senators agreed, however, as to how the Senate should respond to the president’s speech. According to Pennsylvania senator William Maclay, South Carolina senator Pierce Butler thought that “the Speech was committed rather too hastily” and “made some remarks on it.” When Vice President Adams called Butler to order for his criticism, Maclay wrote that Butler “resented the call, and some Altercation ensued.”3

A few days later, the committee presented a draft response to the Senate, which assured the president that the Senate would address each issue that he mentioned, point by point. Maclay, who was becoming a staunch opponent of the Washington administration, objected to the response. He called it “the most Servile Echo” he ever heard, and while the Senate did amend some sections of the original draft, Maclay complained that many clauses were passed without roll-call votes, leaving opponents to accept them “in silent disapprobation.” Meanwhile, the House of Representatives followed the same procedure, meeting to collaborate on a response, a process that proved both “time-consuming and contentious.” Once the House and Senate finally approved their drafts, each body then agreed to wait on the president en masse at his residence to present their responses in person. Following these formal presentations, the president then delivered his own responses.4

The ceremonial spectacle of these proceedings struck some members as obsequious and unnecessary, including Maclay, who worried that the response could be considered by the president’s administration as a tacit approval of its policies. “It was a Stale ministerial Trick in Britain, to get the Houses of parliament to chime in with the speech, and then consider them as pledged to support any Measure which could be grafted on the Speech.” A foreign observer who witnessed both the president’s speech and Congress’s responses noted that the exchange “looked completely like that practiced in England between the King and Parliament” except for the fact that “the next day not one voice was raised in the two Houses to attack any part whatever of the address.” The opposition remained silent.5

As partisan factions developed during Washington’s administration, the process of drafting and agreeing to a single institutional response became impractical. Washington interpreted the Constitution’s directive “from time to time” to mean once a year, and every president since Washington has followed this precedent. This meant that year after year, both the Senate and House spent days, and sometimes weeks, during Washington’s presidency tediously debating their respective responses paragraph by paragraph, arguing over word choice and overall tone. In addition, those in the Senate minority remained frustrated with Senate responses that supported administration policies and ignored dissenting views.

In December 1795 Washington delivered his annual address at the first session of the Fourth Congress, six months after the Senate had convened in a special executive session to consider the controversial Jay Treaty. The Senate’s rancorous debate over the treaty had deepened the partisan divisions among senators, with the majority pro-administration Federalists supporting it and anti-administration Democratic Republicans voting in opposition. The Senate approved the treaty for ratification by the slimmest margin. In his speech, Washington referred to the treaty, declaring that the “summary of our affairs, with regard to the Foreign powers between whom and the United States controversies have subsisted . . . opens a wide field for consoling and gratifying reflections.”6

The treaty’s opponents felt neither consoled nor gratified. When the draft of the Senate’s response included similar praise for the treaty, the Democratic-Republicans objected. Virginia senator Stevens Thomson Mason argued that referring to the treaty in this way served only to rekindle animosities among senators. “The minority on that occasion were not now to be expected to recede from the opinions they held then, and they could not therefore join in the indirect self-approbation which the majority appeared to wish for.”7

Virginia senator Henry Tazewell not only objected to the passage about the treaty, but he questioned the practice of a congressional response altogether, asking “what had given rise to the practice of returning an answer of any kind to the President’s communication to Congress in the form of an Address? There was nothing . . . in the Constitution, or in any of the fundamental rules of the Federal Government which required that ceremony from either branch of the Congress.” Tazewell’s observation was true, but many in Congress clung tight to the pageantry and ceremonial trappings of the executive-legislative exchange.8

Despite the protests of the Democratic-Republicans, attempts to remove the offending passages from the Senate’s response failed. The Senate then approved what was essentially the majority’s response to the annual address on a party-line vote of 14-8. While responses to Washington’s remaining annual addresses and those of John Adams do not appear to have been debated quite as intensely, the strong Federalist majorities in the Senate of that era meant that the minority voice remained unheard.9

When Congress moved from Philadelphia to the newly created capital city of Washington in the District of Columbia in 1800, the tradition of the executive-legislative exchange continued. President Adams presented his final annual address to Congress in person at the Capitol, and both the Senate and House presented responses to the president at his new residence. Unlike Philadelphia, however, where Congress Hall was a mere block from the president’s residence, in the District of Columbia the President’s House was more than a mile from the Capitol, making the trip less convenient. This was one of the reasons given by President Thomas Jefferson in 1801 when he chose to send his message to Congress in writing. He further suggested that the Senate and House need not prepare their official replies:

The circumstances under which we find ourselves at this place rendering inconvenient the mode heretofore practiced, of making by personal address the first communications between the legislative and executive branches, I have adopted that by message, as used on all subsequent occasions through the session. In doing this I have had principal regard to the convenience of the legislature, to the economy of their time, to their relief from the embarrassment of immediate answers, on subjects not yet fully before them, and to the benefits thence resulting to the public affairs.10

For the rest of the 19th century, and into the 20th, presidents followed Jefferson’s example, and Congress stopped officially replying to the president. The annual message to Congress became a lengthy report that laid out the activities and financial needs of the executive branch and included policy recommendations and a summary of foreign affairs. This was the case until 1913, when Woodrow Wilson announced that he would read his annual address to Congress in person.

Wilson understood the power of public opinion in pressuring Congress to support his agenda, so he tailored his speech to appeal to a much wider audience—the American public. He kept the address short but visionary, hoping to persuade and move his audience through emotional rhetoric. According to press reports, Wilson’s in-person performance was a “triumph.” His successors continued the tradition of in-person delivery, and the State of the Union Address became a platform that elevated the priorities of the president and his party. Even more so than during the nation’s founding era, members of the opposing political party found themselves without a formal role to play in the annual event. The advent of television in the 1940s and ʼ50s and the shift of the speech delivery from daytime to prime time in 1965 further expanded the reach of the president’s message, prompting minority leadership in Congress to finally develop a coordinated response. In 1966 Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen and House Minority Leader Gerald Ford recorded a 30-minute rebuttal which aired on major television networks a week after the president’s speech. The opposition response was born.11

Today, the opposition response is broadcast live immediately following the president’s speech. It has become an integral part of this annual ritual, anticipated and discussed almost as much as the address itself—thanks in part to social media platforms. No doubt the Democratic-Republicans of the early 19th century would have appreciated this innovation. What began in the Senate and House as congressional responses expressing the approbation of the president’s majority party has evolved into an opposition response by the other national party, reflecting the complexity of both party politics and executive-legislative relations and demonstrating the delicate balance of power between discordant forces in our system of government.

Notes

1. U.S. Constitution, Article II, section 3.

2. Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 2nd sess., January 8, 1790, 102–4.

3. Ibid., 104; Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., 20, 22–23, 26–27; Kenneth R. Bowling and Helen E. Veit, eds., Diary of William Maclay and Other Notes on Senate Debates, vol. 9 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 180.

4. Bowling and Veit, Diary of William Maclay, 181; “A ‘Troublesome and Greatly Derided Custom’ — Answering the Annual Message,” History, Art, & Archives, United States House of Representatives, Whereas: Stories from the People’s House, https://history.house.gov/Blog/2016/January/1-12-LyonResponse/, accessed January 19, 2024.

5. Bowling and Veit, Diary of William Maclay, 181; Letter from Louis Guillaume Otto to Comte de Montmorin, January 12, 1790, in Charlene Bangs Bickford, Kenneth R. Bowling, Helen E. Veit, and William Charles diGiacomantonio, eds., Correspondence, Second Session: October 1789–14 March 1790, vol. 18 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 196–97.

6. Annals of Congress, 4th Cong., 1st sess., 11.

7. Ibid., 15–16.

8. Ibid., 21.

9. Ibid., 22–23.

10. Senate Journal, 7th Cong., 1st sess., December 8, 1801, 156.

11. James W. Ceaser, Glen E. Thurow, Jeffrey Tulis and Joseph M. Bessette, “The Rise of the Rhetorical Presidency,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 11, No. 2 (Spring, 1981): 158–71; “Wilson Triumphs with Message,” New York Times, December 3, 1913, 1.

|

| 202310 10The First National Burial Ground: Congressional Cemetery

October 10, 2023

When Pierre L’Enfant produced his design for the new federal city in 1791, his plan did not include burial grounds. With the relocation of the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia set to happen by 1800, DC’s commissioners anticipated the influx of population that would follow and set aside land in 1798 for two cemeteries on the outskirts of the city, one on the west side and the other on the east. When the site on the east side of the city proved to be unsuitable for burials, a group of parishioners of Christ Church on Capitol Hill established a new burial ground two miles from the Capitol, known by the 1830s as Congressional Cemetery.

When Pierre L’Enfant produced his design for the new federal city in 1791, his plan did not include burial grounds. With the relocation of the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia set to happen by 1800, DC’s commissioners anticipated the influx of population that would follow and set aside land in 1798 for two cemeteries on the outskirts of the city, one on the west side and the other on the east. When the site on the east side of the city proved to be unsuitable for burials, a group of parishioners of Christ Church on Capitol Hill established a new burial ground along the Anacostia River, two miles from the Capitol. In time this cemetery came to be regarded as the first national burial ground, known by the 1830s as Congressional Cemetery.1

Just a few months after the Christ Church cemetery opened, Senator Uriah Tracy of Connecticut became the first member of Congress to be buried there. A Revolutionary War veteran and former president pro tempore of the Senate, Tracy died on July 19, 1807, and a few days later was interred in the cemetery “with the honors due to his station and character, as a statesman.” A member of the House of Representatives was buried there in 1808, and the following year Senator Francis Malbone of Rhode Island, who died on the steps of the Capitol after only three months in office, was interred there as well. Vice President George Clinton was interred there in 1812 and Vice President Elbridge Gerry followed in 1814, each escorted to his final resting place by a grand procession down Pennsylvania Avenue.2

The Washington Parish Burial Ground, as it was formally known at the time, was a public cemetery open to all, including African Americans (though in a segregated portion of the grounds). In addition to serving as the final resting place for some members of Congress, the cemetery also accommodated Senate officers, staff members, and even laborers who worked at the Capitol. William Swinton, a stonecutter who had worked on construction of the Capitol, was the first individual interred there in April 1807, just days after the cemetery was created. The Senate’s first doorkeeper and sergeant at arms, James Mathers, was laid to rest in the cemetery in 1811, as was the first secretary of the Senate, Samuel Otis, in 1814. Numerous members of the Tims family, who worked as doorkeepers, messengers, and pages in the early Senate, also found their final resting place in the cemetery.

During the early years of the 19th century, embalming practices did not allow for long-distance transportation of the deceased, making local burial a necessity. Consequently, when a member of Congress died during a congressional session, he was typically buried in a local cemetery. Between 1800 and 1830, practically every member of Congress who died in office was buried at this site. Facing this reality, in 1817 Christ Church donated 100 burial sites for the interment of representatives and senators. In 1820 it opened those sites to the families of members of Congress as well as the heads of cabinet departments. A few years later, the church provided 300 additional burial sites for members of Congress and government officials. Around this time, the site became popularly known as Congressional Cemetery.3

To give distinction to the gravesites of lawmakers, Congress in 1815 commissioned Capitol architect Benjamin Latrobe to design a stately monument to honor each of the deceased members. Latrobe’s design featured a large cube topped with a small, conical dome made from the same sandstone used to construct the Capitol. An engraved marble plaque identified the deceased. Latrobe believed the monuments would be more durable than the typical marble headstones in use at the time.

As years went by, improvements in embalming practices and in transportation—particularly with the construction of railroads—made it possible to return the deceased to home-state cemeteries. It became more common for members to be temporarily interred at the cemetery, then later transported for a home-state burial, leaving the space beneath the monument empty. For decades to come, Congress continued to add a monument to the cemetery whenever a member died in office, regardless of whether or not mortal remains ever rested there. By the 1870s, the cemetery held more than 150 of the Latrobe-designed monuments, arranged in long rows, although only about half actually covered a body. They became known as “cenotaphs,” which means “empty tomb.”4

Unfortunately, the stone markers weathered poorly over time and became increasingly unpopular with Washingtonians, including some members of Congress. One representative complained that the cenotaphs resembled a huge “dry-goods box with an old-fashioned bee-hive on top . . . , the most complete consummation of hideousness that it has ever been my misfortune to observe in a cemetery.” Above all, prayed another, “I hope to be delivered from dying—[at least] while Congress is in session.” When a bill was introduced in 1876 to require production of a granite monument matching the existing cenotaphs for future representatives and senators interred at the cemetery, Representative (and later Senator) George Hoar succeeded in striking the requirement from the bill. “It is certainly adding new terror to death,” Hoar stated, to require deceased members to lie beneath a cenotaph. This marked the end of new cenotaphs in Congressional Cemetery for nearly a century. A number of members of Congress were interred there in the years following, but those graves were marked with small headstones. One last cenotaph was placed in 1972 to mark the passing of House Majority Leader Hale Boggs who perished in a plane crash that year, his body never recovered.5

Though Congress did not have a formal relationship with Christ Church or ownership of the cemetery, it played an important financial role in the burial ground’s care and maintenance. Following the first congressional burials in the early 19th century, Christ Church officials hoped the donation of burial plots to Congress would strengthen ties with lawmakers and lead to financial support for the cemetery as a quasi-public institution. In 1824 Congress appropriated $2,000 to Christ Church to build a wall around the cemetery. Congress contributed more funds in the 1830s to build a house for the cemetery caretaker, plant trees, and “otherwise improve the interment of members of Congress and other officers of the General Government.” Between 1832 and 1834, Congress also appropriated $2,800 to build a vault to hold bodies awaiting burial, a service provided to representatives and senators free of charge. (Former First Lady Dolley Madison was interred there for three years while funds were raised to allow her to be moved for burial at her husband’s Montpelier estate in Virginia.) By 1846 Congress had appropriated $10,000 for upkeep and repairs. That year, when Congress provided funds for the cemetery and the road that led to from the Capitol, it used the name “Congressional Burial Ground,” solidifying its special relationship to the cemetery.6

With the establishment of Arlington Cemetery after the Civil War, Congressional Cemetery yielded its active role as the chief national burial ground. By that time, the cemetery had been the site for grand funeral services for deceased presidents William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and John Quincy Adams, and the final resting place of U.S. Attorney General William Wirt and U.S. Secretary of State John Forsythe. During the late 19th century, notable individuals from Senate and House history continued to be interred there, including former sergeant at arms Dunning McNair; Isaac Bassett, one of the first Senate pages and later a longtime doorkeeper of the Senate; Joseph Gales and William Seaton, early newspapermen who recorded congressional debates; and Anne Royall, one of the first women journalists to cover Congress. The cemetery also continued to serve private citizens well into the 20th century, eventually providing the resting place for 60,000 individuals, including pioneering photographer Matthew Brady, famed military composer and conductor John Philip Sousa, and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, a Washington native.

By the mid-20th century, Congress had long ceased providing appropriations for the cemetery, and Christ Church’s congregation lacked the resources to maintain it. Despite efforts by groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution to generate public and congressional support for the historic site, it gradually fell into disrepair. In 1976 a nonprofit organization, the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery (APHCC), assumed management of the site. After decades of neglect, however, the APHCC struggled to keep up with the overgrown grass and weeds, repair broken monuments and crumbling private vaults, and protect the grounds from vandalism. That year Congress passed legislation authorizing the architect of the Capitol to assist in the maintenance of the cemetery and appropriated funds for that purpose. Congress did not provide additional funds in the years following, however, and by 1997 Congressional Cemetery had fallen on such hard times that the National Trust for Historic Preservation added it to its list of most endangered historic sites. Neighborhood volunteers—especially dog owners who frequented the grounds with their pets and formed the K9Corps at Historic Congressional Cemetery—worked with the APHCC to raise money and devoted hundreds of hours to bringing the cemetery back to life. In 1997 volunteers from all five branches of the military gathered at the site to mow the grass and repair headstones, an event that continues to be an annual tradition. As the cemetery’s 200th anniversary approached, Congress once again provided monetary support, passing legislation in 1999 and 2002 to establish an endowment for its ongoing restoration and maintenance. The cemetery was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2011.7

Through the efforts of local volunteers and with funds appropriated by Congress, Congressional Cemetery, the first national burial ground, has been restored as both a meaningful community space and a monument to the elected officials who died while serving their nation in Washington, DC. Eighty-four representatives, fourteen senators, and five individuals who served in both houses of Congress are interred at Congressional Cemetery alongside the cenotaphs that memorialize the passing of dozens more.

Notes

1. Abby Arthur Johnson and Ronald Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol: Congressional Cemetery and the Memory of the Nation (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2012), 9–14.

2. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol, 23–24, 53–54.

3. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol, 35; Rebecca Boggs Roberts and Sandra K. Schmidt, Historic Congressional Cemetery (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2012), 7.

4. Roberts and Schmidt, Historic Congressional Cemetery, 25–27.

5. Congressional Record, 44th Cong., 1st sess., May 15, 1876, 3092–93; Kim A. O’Connell, “A Monumental Task,” Preservation (July/August 2009): 18–19; History of the Congressional Cemetery, S. Doc. 72, 59th Cong., 2nd sess., December 6, 1906, 35.

6. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol, 33, 36–37; History of the Congressional Cemetery, 11–15.

7. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol, 223–64; “Ruin of Tombs,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 31, 1890, 9; House of Representatives, Committee on Interior Affairs, “Relating to the Preservation of the Historical Congressional Cemetery,” H. Rpt. 667, 97th Cong., 2nd sess., July 27, 1982; Betsy Crosby, “To Hell and Back: The Resurrection of Congressional Cemetery,” Preservation (January/February 2012): 28–33; “The Cemetery Lost Its Aura,” Washington Star, September 19, 1971, 1; “New Panel Eyes Cemetery Bill,” Washington Post, July 28, 1976, A15; “A Gentle Reminder of Congressional History, 20 Blocks from Capitol Hill,” Roll Call, September 18, 1988, 31; “Congressional Cemetery Could Get Funding,” Roll Call, July 26, 2001, 46.

|

| 202308 11Give Us a (Summer) Break: Origins of the August Recess

August 11, 2023

The arrival of August means that the Senate is out of session and in the midst of its annual summer recess. Senators’ now-traditional time away from Washington, DC, during the “dog days” of summer can be traced back to the mid-20th century when workloads were growing, legislating was becoming a full-time, yearlong job, and the need to modernize Congress to meet the demands of the 20th century was becoming more evident. In the 1960s, Senator Gale McGee of Wyoming relentlessly worked to convince his colleagues that to modernize the Senate and meet those demands, they would have to take a summer break.

The arrival of August means that the Senate is out of session and in the midst of its annual summer recess. Senators’ now-traditional time away from Washington, DC, during the “dog days” of summer can be traced back to the mid-20th century when workloads were growing, legislating was becoming a full-time, yearlong job, and the need to modernize Congress to meet the demands of the 20th century was becoming more evident. In the 1960s, Senator Gale McGee of Wyoming relentlessly worked to convince his colleagues that to modernize the Senate and meet those demands, they would have to take a summer break.

From 1789 until the 1930s, Congress convened for its first regular session in December and typically adjourned in spring or midsummer. After months away from Washington, members of Congress would return for a short second session in December that adjourned on March 3. Occasionally, extraordinary sessions or the demands of war kept Congress in session longer, but generally senators agreed with Vice President John Nance Garner, who reportedly proclaimed, “No good legislation ever comes out of Washington after June.”1

By the late 1950s, however, the schedule had changed and workloads had grown. Adoption of the Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution in 1933 moved the start of each session of Congress to January. The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 included a provision that “except in time of war or during a national emergency,” Congress was to adjourn by the last day in July, but this rarely happened in practice. The dramatic growth of the federal government since the Great Depression brought greater oversight responsibilities and increasingly complex appropriations work to lawmakers, all on top of their need to address national problems like civil rights and the challenge of governing the world’s largest economy. From 1949 to 1951, the earliest Congress adjourned was October 19. In 1956 Congress adjourned on July 27—marking the last time the Senate adjourned before the first of August.2

Senators began to feel the effects of these longer and busier legislative sessions. Short tempers and testy exchanges accompanied work in the hot Washington summers. In 1959 Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine warned of the Senate’s increasing workload. “The pressures under which Congress works every year at this time of year . . . create disorder,” she complained, as well as “confused thinking, harmful emotions, destructive tempers, unsound and unwise legislation, and ill health with the very specter of death hanging over Members of Congress.” (If that sounds dramatic, keep in mind that in the 1950s, senators died in office at a rate of about two per year.) Smith proposed an annual break from August to mid-November, but the Senate ignored her words of caution.3

In 1960, when the growing workload resulted in another long session that lasted into September, support for a summer recess grew. In 1961 freshman senator Gale McGee proposed an annual break to last from June to October, gaining the support of 32 co-sponsors. McGee argued that the long sessions prohibited many senators from returning to their home states, which had a deleterious effect on their family lives. “We are faced in the Senate with the fact that the work in the Senate is never finished,” he stated, adding it was time “to work out a habit of living that will enable us to rise to these challenges with a minimum disruption of normal family living.” During the 1950s, an influx of younger senators meant that more senators came to Washington with spouses and children in tow. In 1961 there were at least 141 school-age children of senators in and around the DC area. McGee was 46 years old with four children of his own, and almost half of his resolution’s co-sponsors were aged 50 and under.4

Among McGee’s most ardent supporters were many wives of senators and representatives. Bethine Church, wife of Idaho senator Frank Church and the chair of a committee created by the Democratic Congressional Wives Forum and the Republican Congressional Wives Club to study the issue, presented to the Senate Rules Committee a petition of support signed by more than 170 congressional spouses. In testimony to the committee, Church explained that Senate wives typically brought their children back to their home states after school let out for the summer. “It is important,” she stated, “to keep children close to the State which their father represents.” With the Senate in session during the summer, senators stayed in Washington while the family was absent. Once the session ended in the fall, senators traveled back home to meet with constituents (or, in election years, to campaign) just as their children returned to school in Washington. “The average Congressman with school-age children,” Church concluded, “is separated from his family almost half of the year.”5

A summer recess was also popular among senators from the West and Midwest for whom travel back home was costly and difficult to make in the midst of a session. Over two-thirds of McGee’s co-sponsors represented states away from the East Coast. Senator Jack Miller of Iowa stated, “I don’t know a better place in my State for me to obtain true grassroots thinking on problems of people of my State than at the county fairs,” and long sessions meant that he could not attend any of them.6

Unfortunately for McGee, a change to the congressional calendar required the cooperation of the House of Representatives. The Constitution states that neither the House nor the Senate can adjourn for longer than three days without the consent of the other. Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, a 79-year-old bachelor without children, vehemently opposed a scheduled summer recess, declaring, “It’s the greatest nonsense I ever heard.” In light of this opposition from Rayburn and other older, long-serving members, no action was taken on McGee’s resolution.7

In 1962 the Senate met from January to October with no recess. Just before adjournment that year, McGee renewed his call for a summer recess and got the attention of Senate leadership. In early 1963, Majority Leader Mike Mansfield of Montana expressed support for a summer recess and appointed an informal committee of Democratic senators, led by Senator Mike Monroney of Oklahoma, to suggest ways of speeding up Senate business and changes to the Senate calendar. In March Monroney’s group recommended that the Senate take a short break that session at the end of August. By May, however, Mansfield was already backtracking, saying that a recess would not be possible that year. An anonymous senator, likely McGee, speculated that Mansfield would not commit to an August break since that could be seen as a concession that the session would continue into the fall. That year, the Senate adjourned in December without having taken a break longer than a three-day weekend.8

By 1965 both the House and Senate were prepared to thoroughly examine their way of doing business, and McGee suddenly found himself with a more receptive audience. The Joint Committee on the Reorganization of Congress held more than a dozen hearings that year to explore ways to improve Congress’s efficiency and effectiveness. While McGee still highlighted the benefits of a recess for families, he began to emphasize that a summer break was essential to a broader modernization of the Senate. At a Joint Committee hearing in May, he asserted that “our annual race with the calendar and our perennial guessing game as to when we shall adjourn for the session are symbols of inefficiency and relics of the past.” He argued that mentally and physically tired senators rushed to adjourn at the end of long sessions, leading to good bills being tossed by the wayside while other bills passed without proper debate and scrutiny. McGee argued that a series of scheduled breaks, including a month off in August, would make it “easier, more orderly, and more predictable to pace ourselves during the arduous full legislative year.” The Joint Committee agreed. In its 1966 report, the committee recommended that the House and Senate adopt reforms with the goal of adjourning by July 31, but if the session had to be extended, neither house would meet during the month of August.9

Congress would not adopt the full array of the Joint Committee’s recommendations for a number of years, but in the meantime the Senate was ready to try out a summer recess. In 1968 the Senate took a month-long break in August to allow members to attend the party nominating conventions. If the Senate could break for the conventions in election years, some asked, why not in other years? The following year the Senate recessed from August 13 to September 3. Young reformers gleefully left town, while older senators grumbled. “There’s too much work piling up,” snarled one. “Now we’ll be here till Christmas!” Come September, reviews of the experimental recess were mixed. It certainly was “no vacation,” insisted George Aiken of Vermont, who discovered that his Senate work followed him home. But even critics acknowledged that the break provided useful opportunities for family gatherings and connection with constituents.10

Congress passed the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 in October of that year, which mandated that in odd-numbered years both the House and Senate adjourn for a summer recess in August. On August 6, 1971, the Senate began its first official summer recess. While the statute did not mandate a break in even-numbered years—senators chose to maintain flexibility during campaign seasons—the Senate took shorter breaks in August of election years and, beginning in the 1990s, began taking longer August breaks every year.11

On rare occasions, the Senate has chosen to shorten its break or even to forgo the August recess entirely. For example, in 1994 during a heated debate over healthcare legislation, Majority Leader George Mitchell of Maine delayed the Senate’s recess until August 25. The Senate interrupted its summer recess in 2005 to pass an emergency relief bill in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. The Senate cancelled the August recess in 2018 to consider appropriations bills. Such cases remain the exception. By practice and by law, the Senate’s August recess has become a cherished tradition.12

Notes

1. Garner’s line was first attributed to him by Senator Willis Robertson in 1956. Congressional Record, 84th Cong., 2nd sess., July 12, 1956, 12419.

2. Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, Public Law 79–601, 79th Cong., 2nd sess., August 2, 1946, 60 Stat. 831. For a complete list of congressional session dates, see “Dates of Sessions of the Congress,” United States Senate, accessed July 14, 2003, https://www.senate.gov/legislative/DatesofSessionsofCongress.htm.

3. Congressional Record, 86th Cong., 1st sess., September 10, 1959, 18679, 18880.

4. S. Con. Res. 16, 87th Cong., 1st sess; Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Adjournment of Congress: Hearing on S. Con. Res. 6 and S. Con. Res. 16, 87th Cong., 1st sess., August 2, 1961, 10.

5. Adjournment of Congress, 7, 9–13..

6. Adjournment of Congress, 16.

7. “Rayburn Opposes Summer Recess for Congress,” Hartford Courant, May 10, 1961, 24A; “Yes Dear, Father Tried…but Mr. Rayburn Said No,” Boston Globe, August 3, 1961, 14.

8. “Senate Eyes New Set-Up for Meetings,” Baltimore Sun, January 10, 1963, 1; “Mansfield Proposes Easier Senate Pace, Six Recesses,” Wall Street Journal, January 11, 1963, 5; “Senate Unit Proposes Legislative Speed Up,” Washington Post, March 31, 1963, A2; “Mansfield Does Not Believe Summer Recess is Possible,” Washington Post, May 12, 1963, B2; “To Move Congress Out of its Ruts,” New York Times, April 7, 1963, SM39.

9. Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Subcommittee on Standing Rules of the Senate, Reorganization of Congress: Hearing on S. Con. Res. 2 and S. 1208, 89th Cong., 1st sess., February 24, 1965; Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress, Organization of Congress: Hearings Pursuant to S. Con. Res. 2, Part 2, 89th Cong., 1st sess., May 20, 1965, 332–38; Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress, Organization of Congress: Final Report of the Joint Committee on the Organization of the Congress, 89th Cong., 2nd sess., S. Rpt. 1414, July 28, 1966, 55–56.

10. “Recess for Congress,” Baltimore Sun, July 22, 1968, A8; Congressional Record, 91st Cong., 1st sess., August 13, 1969, 23660; “Vacation Breather Refreshes Capitol Hill—But Work Piles Up,” Christian Science Monitor, September 13, 1969, 7. For dates of recesses, see the “Sessions of Congress,” Congressional Directory, 117th Cong. 2nd sess., October 2022, 540–58.

11. Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, Public Law 91-510, 91st Cong., 2nd sess., October 26, 1970, 84 Stat. 1193; Congressional Record, 91st Cong., 2nd sess., October 5, 1970, 34945; “Senate Churns Out Bills, Recesses,” Boston Globe, August 7, 1971, 5; “Regular Recesses Help Congress Do More Work,” Los Angeles Times, October 25, 1975, 1.

12. H. Con. Res. 179, 101st Cong., 1st sess., 1989; “The Longest Debate,” Washington Post, August 19, 1994, G1; “Health Reform Vote May Hang on Senate Recess,” Los Angeles Times, August 23, 1994, A1; Susan Davis, “Mitch McConnell Cancels Senate’s August Recess,” June 5, 2018, accessed July, 10, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2018/06/05/617219548/mitch-mcconnell-cancels-senates-august-recess.

|

| 202303 08Enriching Senate Traditions: The First Women Guest Chaplains

March 08, 2023

The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857, and for more than 100 years, guest chaplains had all been men. That changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition.

The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. All Senate chaplains have been men of Christian denomination, although guest chaplains, some of whom have been women, have represented many of the world's major religious faiths.

The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857. That year, with many senators complaining that the position had become too politicized, the Senate chose not to elect a chaplain. Instead, senators invited guests from the Washington, D.C., area to serve as chaplain on a temporary basis. In 1859 the practice of electing a permanent chaplain resumed and has continued uninterrupted since that time, but the practice of inviting a guest chaplain to occasionally open a daily session also continued. While it is possible, and perhaps likely, that the Senate selected guest chaplains prior to 1857, surviving records from the period are insufficient to make that determination.

By the mid-20th century, guest chaplains were frequently offering the Senate’s opening prayer. Clergy visiting the nation’s capital often communicated their desire to serve as a guest chaplain to their home state senators who would nominate them for the role. In the 1950s, this practice became so popular among senators that Chaplain Frederick Brown Harris, who served nearly 25 years as Senate chaplain, complained to Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas that guest chaplains had replaced him 17 times over the course of just a few weeks. Leader Johnson assured Harris that he would ask senators “to restrict the number of visiting preachers,” but the frequency of the guests persisted.1

During the 1960s, Harris suffered from a series of medical issues and was less engaged in his official duties. Consequently, Harris’s unplanned absences prompted new problems for the Senate majority leader, now Mike Mansfield of Montana, whose staff was forced to arrange for last-minute guest chaplains. Infrequently, they called on senators to offer the prayer. Further irritating the majority leader, Harris unwittingly hosted guest chaplains who used the “forum to present their own particular litanies” and political viewpoints, thereby violating the Office of the Chaplain’s tradition of nonpartisan, nonpolitical service.2

Such issues prompted Senate leaders to reevaluate policies related to the appointment of guest chaplains. When Reverend Harris passed away in early 1969, Majority Leader Mansfield and Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois created an informal, bipartisan committee on the “State of the Senate Chaplain.” Upon concluding their study, the leaders informed Harris’s successor, Chaplain Edward L. R. Elson, of a policy change: “It would be our judgement that under ordinary circumstances a regular practice of inviting two guest chaplains per month is now in order.” Also, “In instances when you are ill or unavoidably absent, we would expect you to ask a brother clergyman to fill in temporarily in your stead.” The new policy was intended to standardize and bring order to the guest chaplain practice.3

For more than 100 years, guest chaplains had been men, but that changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition. A 1942 graduate of the Union Theological Seminary, Rowland became a minister in 1957, after the Presbyterian Church allowed for the ordination of women. She was an author and associate minister in Cincinnati, Ohio, before joining the United Presbyterian Board of Christian Education in Philadelphia, where she directed its educational loans and scholarships program. When Chaplain Elson invited her to lead the Senate’s opening prayer, Rowland recognized the historical significance of his offer. “It’s an honor to pray with and for such an august body,” she explained to the press. “I’m not unmindful of the women’s lib[eration] angle to my performance. But the prayer, like any other I have offered, is still to God. I’ve kept that in mind while I’ve been working on it.”4

Generally, the opening of the Senate’s daily session is sparsely attended. Six senators were present in the Chamber on July 8, 1971, for this historic event, including the Senate’s only woman senator, Margaret Chase Smith of Maine. Senate President pro tempore Allen Ellender of Louisiana called the Senate to order at noon, then introduced Dr. Rowland as “the very first lady ever to lead the Senate in prayer.” Rowland began:

O God, who daily bears the burden of our life, we pray for humility as well as forgiveness. As our nation plays its part in the life of the world, help us to know that all wisdom does not reside in us, and that other nations have the right to differ with us as to what is best for them.

Rowland later reflected on the event: “I’m pleased not for myself but for the fact the Senate has reached the point where they feel it is normal to invite a woman to do this.”5

But it wasn’t normal yet, and three years would pass before another woman delivered the Senate’s opening prayer. On July 17, 1974, Sister Joan Doyle, president of the Congregation of Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary headquartered in Dubuque, Iowa, became the second woman and the first Roman Catholic nun to offer the opening prayer in the Chamber. Her sponsor, Iowa senator Dick Clark, introduced her. At the conclusion of Doyle’s prayer, Minority Leader Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania praised her “gentler touch” for preparing senators to enter “into the brutal conflicts of the day.” Senator Margaret Chase Smith had retired in 1973, and Senator Clark reflected on the lack of women senators in the Chamber that day. “I hope it won’t be three more years before another woman is here, not only for the opening prayer, but as a member of the Senate.” It took more than five years, in fact, for the next woman senator to take a seat in the Chamber. On January 25, 1978, Muriel Humphrey was appointed to fill the seat left vacant when her husband, Senator Hubert Humphrey, passed away.6

Since 1974 other women have followed in the footsteps of Reverend Rowland and Sister Doyle, although the number of female guest chaplains remains small. In 2008 the Reverend Dr. Patricia Bryant Harris made history as the first African American woman to give the Senate’s opening prayer. “It had a lot of meaning to me personally, to be a part of that history,” Reverend Harris said in an interview. “That is now history as part of the Congressional Record.”7

The chaplain has been an integral part of the Senate community since the election of the first chaplain, Samuel Provoost, on April 25, 1789. Today, chaplains and guest chaplains, now men and women, deliver the opening prayer each day that the Senate is in session. As Senator Mary Landrieu of Louisiana remarked in 2012, "It is good that we take a moment before each legislative day begins in the Senate to still ourselves and ask for God's grace and guidance on the work that we have been called to do."8

Notes

1. Congressional Record, 91st Cong., 2nd sess., August 20, 1970, 29611.

2. “Chaplain Absent, Senator Gives Prayer,” Hartford Courant, September 20, 1963, 25B; “Senator Takes Chaplain’s Place,” Washington Post, Times Herald, September 2, 1964; Memorandum from Richard Baker to Mike Davidson, September 19, 1985, in the files of the Senate Historical Office.

3. Mike Mansfield and Everett Dirksen to Dr. Edward L. R. Elson, Chaplain, April 29, 1969, in the files of the Senate Historical Office.

4. “Barrier to Fall: Woman Will Lead the Senate in Prayer,” Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), July 4, 1971, A-10; “A Woman, Praying for the Senate,” Washington Post, July 9, 1971, B2.

5. Congressional Record, 92nd Cong., 1st sess., July 8, 1971, 23997; “Barrier to Fall: Woman Will Lead the Senate in Prayer.”

6. “Nun Gives Prayer in Senate,” Catholic Standard, July 25, 1974.

7. Nicole Gaudiano, “Del. Pastor makes history in U.S. Senate,” News Journal (Wilmington, DE), July 11, 2008, B1.

8. “At Sen. Landrieu’s Invitation, Louisiana Chaplain Offers Opening Prayer for U.S. Senate,” Targeted News Service, Feb. 28, 2012.

|

| 202012 30When a New Congress Begins

December 30, 2020

On January 3, 2021, the U.S. Senate will convene to open the 117th Congress. The Senate typically operates according to long-standing rules, traditions, and precedents, and the first day of a new Congress is no exception. On this day, the Senate follows a well-established routine—parts of which date back to the first Congress in 1789. The Constitution mandates that Congress convene once each year at noon on January 3, unless the preceding Congress designates a different day. In odd-numbered years, following congressional elections, a “new” Congress begins.

On January 3, 2021, the U.S. Senate will convene to open the 117th Congress. The Senate typically operates according to long-standing rules, traditions, and precedents, and the first day of a new Congress is no exception. The Constitution mandates that Congress convene once each year at noon on January 3, unless the preceding Congress designates a different day.1 In odd-numbered years, following congressional elections, a “new” Congress begins. From 1789 until 1934, a new Congress began on March 4. The Twentieth Amendment, adopted in 1933, changed the opening date to January.

Regardless of the change in date, the first day of a new Congress for the Senate follows a well-established routine—parts of which date back to the first Congress in 1789.

The day begins with the opening prayer and recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance, followed by the swearing-in of senators-elect (and sometimes appointed senators), the establishment of a quorum, notifications to the House of Representatives and the president, and often the election of a president pro tempore and other officers. Unlike the House of Representatives, the Senate, as a continuing body, does not have to adopt or readopt its rules with each new Congress. Article 1, section 3 of the U.S. Constitution provides for staggered six-year terms for senators. The Senate is divided into three classes for election purposes, and every two years only one-third of the senators are elected or reelected, allowing two-thirds to continue serving without interruption.

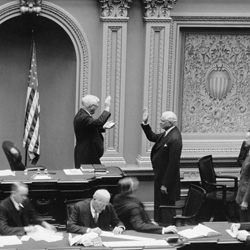

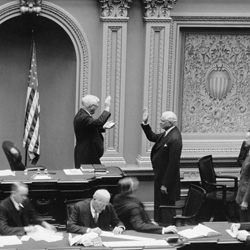

Before senators-elect can begin exercising their legislative responsibilities, each must present his or her certificate of election and then take the prescribed oath of office in an open session of the Senate. The certificate of election, issued by the governor from the incoming member’s state, confirms that the person was duly elected. Affixed with the state’s official seal, it is delivered to the secretary of the Senate for official recording. After the opening prayer and recitation of the pledge, the vice president of the United States, who serves as the president of the Senate, announces the receipt of certificates. Following established tradition, senators-elect are then escorted down the center aisle of the Senate Chamber to the presiding officer’s desk. Typically, the other senator from the member-elect’s state serves as an escort. Occasionally, the senator-elect chooses an alternative or additional escort, such as a former senator or a family member who also served in the Senate.

The vice president, or, in the vice president’s absence the president pro tempore, administers the oath of office. Senators-elect take the oath to defend the Constitution by raising their right hand and agreeing to the words spoken by the presiding officer:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter: So help me God.

Some hold in their left hand a personal Bible or other text of personal significance. The final act in the oath-taking ceremony occurs as the secretary of the Senate invites each newly sworn senator to sign his or her name on a dedicated page in the Senate Oath Book.

Following the official oath-taking ceremony in the Senate Chamber, newly sworn senators join the vice president in the Old Senate Chamber, where they reenact the swearing-in ceremony. Prior to 1987, when the opening day of the Senate was first broadcast on live television, the official swearing-in ceremony was normally off-limits to cameras of any sort. The long-standing ban on photography in the Chamber led newly sworn members to devise an alternative way of capturing this moment for their families, constituents, and posterity. In earlier years, the vice president invited newly sworn senators and their families into his Capitol office for a reenactment for home-state photographers. In 1983 the reenactment ceremony moved to the restored Old Senate Chamber and has been held in that historic setting ever since.

Once the senators-elect have been sworn in, the vice president directs the Senate clerk to call the roll to establish a quorum, which the Constitution requires in order for the Senate to conduct business. The majority leader then moves to adopt resolutions to notify the House and the president that the Senate has a quorum and is ready to proceed. The language of those resolutions has changed very little over the last 230 years. In 1791 the Second Congress convened in Philadelphia. After senators-elect presented their credentials and the vice president administered the oath of office, the Senate passed the following motion:

Ordered, That Messrs. Butler, Morris, and Dickinson, be a committee to wait on the President of the United States, and inform him that a quorum of the Senate is assembled agreeably to the Constitution, and ready to receive any communications he may be pleased to make to the Senate.2

On January 3, 2019, the Senate adopted this resolution:

Resolved, That a committee consisting of two Senators be appointed to join such committee as may be appointed by the House of Representatives to wait upon the President of the United States and inform him that a quorum of each House is assembled and that the Congress is ready to receive any communication he may be pleased to make.3

While the committee members appointed to “wait upon the President of the United States” did so in person in the 18th and 19th centuries, today the committee informs the president by telephone.4

The Senate next proceeds to other administrative business, which often includes the election of the president pro tempore, the secretary of the Senate, the sergeant at arms, and the chaplain. The Senate typically adopts a resolution early in the new Congress to set procedures for operating the Senate during the next two years. The resolution may include committee ratios, committee membership, and other agreements made between the majority and minority parties on the operation of the Senate. This is usually a routine matter approved by unanimous consent agreement, but there have been occasions when the Senate faced unique challenges, making organization difficult. With much of the “housekeeping” out of the way, the Senate is ready to take up legislative and executive business. With each new Congress, all pending legislation and nominations of the previous Congress expire, requiring many bills and resolutions to be reintroduced.

Guests seated in the Senate galleries and those watching from home will note that members often stand behind their Senate desks to deliver their remarks. At the start of each Congress, the desks are reapportioned between the two sides of the Chamber based on the number of senators from the two political parties. For many years, the desks were assigned on a first-come, first-served basis. When a seat became available, the first senator to speak for it won the right to it. Today, at the beginning of each Congress, senators are given the option to change their seats, based on seniority. Three desks that are not assigned in this manner are the Daniel Webster Desk, the Jefferson Davis Desk, and the Henry Clay Desk. Senate resolutions govern the assignment of these desks.

To learn more about the opening day of a new Congress or other Senate traditions, visit Frequently Asked Questions about a New Congress or About Senate Traditions & Symbols.

Notes

1. U.S. Const., amend. XX, § 2.

2. Senate Journal, 2nd Cong., 1st sess., October 24, 1791, 323.

3. “Informing the President of the United States That a Quorum of Each House Is Assembled,” Congressional Record, 116th Cong., 1st sess., January 3, 2019, S5 (daily edition).

4. Valerie Heitshusen, "The First Day of a New Congress: A Guide to Proceedings on the Senate Floor." Congressional Research Service, RS20722, updated December 22, 2020, 4.

|

| 202012 14Christmas Gift Giving in the Senate

December 14, 2020

The Senate is an institution steeped in tradition. While some traditions prove to be long lasting, others come and go. Such is the case with one tradition of gift giving in the Senate around the Christmas holiday.

The Senate is an institution steeped in tradition. While some traditions prove to be long lasting, others come and go. Such is the case with one tradition of gift giving in the Senate around the Christmas holiday.

Christmas was not always an eventful holiday in the Senate. Prior to the 1850s, senators took very little time off while the Senate was in session. The legislative session started in the first week of December and, in the era before widely available railroad service, it was too onerous to travel home for a short holiday break. The Senate was typically in session on December 24, adjourned for Christmas Day, then returned to business on December 26. Not until 1857 did senators resolve to take a recess for the Christmas and New Year holidays. In 1870 Congress passed legislation that made Christmas a holiday for federal employees in the District of Columbia. By the 1890s newspapers reported that attendance in both houses of Congress was “steadily diminishing” as the holiday approached, noting the Capitol was “practically deserted.”1

The absence of senators during a holiday recess meant there was time for those who stayed in town, especially staff, to celebrate the season. Soon, gift giving became part of the Senate’s holiday tradition. On Christmas Day 1862, for example, the Chamber’s messengers presented their supervisor Isaac Bassett—the assistant doorkeeper who began his 64-year Senate career as a page in 1831—with an engraved gold-topped cane to thank him for his service, in particular for “always showing the utmost courtesy to the messengers under his direction.”2

Another notable gift came in 1902, when Senate Sergeant at Arms Daniel M. Ransdell received a package from an unknown sender. Ransdell carefully removed the gold-foil wrapping from the package to find 14 ounces of anthracite coal. Before assuming that he was on the “naughty list,” know that the lump of coal was actually a welcome gift. Ransdell had been short on fuel for heating the Capitol that season.3

In the late 19th century, holiday celebrations—which had long been public displays of revelry—became more focused on children. In the Senate, gift-giving traditions centered on the youngsters employed as Senate pages.

In 1887 California senator Leland Stanford, a multimillionaire, gave each page a five-dollar gold coin at Christmas. Isaac Bassett was charged with dispensing the gift and, though not a rotund man, his white hair and long beard and his “merry eye and cheerful voice” led the pages to dub him Santa Claus.4

Vice President Thomas R. Marshall began a tradition in 1913 of an annual Christmas dinner with the pages in the Senate dining room. Pages were treated to a sumptuous holiday spread and toasted for their hard work. Marshall then offered sage advice to the sated boys on how to succeed after they left the Senate’s employ. Calvin Coolidge continued the tradition when he became vice president in 1921.5

Some senators took advantage of the annual dinner to give the pages tokens of their appreciation. In 1915 Senator George Oliver of Pennsylvania and Senator James Martine of New Jersey gave each page a crisp new dollar bill. The following year Senator Willard Saulsbury of Delaware joined Oliver in giving cash gifts to the 16 pages. For a number of years Senator John Kendrick of Wyoming gave each page a new necktie. In an oral history interview conducted decades later, page Donald Detwiler recalled a Christmas dinner in 1917 at which Senator James D. Phelan of New York presented each page with a book.6

When the vice presidency was vacant in 1923—Coolidge had ascended to the presidency after the death of Warren G. Harding—a newspaper reporter quipped that “tiny Tim,” the smallest of the Senate pages, had lost his Santa Claus because no substitute had emerged to carry on the holiday tradition.7

The pages needn’t have worried. A few days after Christmas, Maud Younger, congressional chairwoman of the National Woman’s Party, learned that the pages might miss their celebration and invited them to her home for a feast. Arkansas senator Thaddeus Caraway donned a Santa Claus suit and arrived at Younger’s home with a bag of gifts. In 1925 Senator Robert Stanfield of Oregon took over the role of Santa and distributed gifts to the pages on the steps of the Capitol.8

When Vice President Charles Dawes revived the Christmas page dinner in 1925, the appreciative pages decided to turn the tables and offer their own gifts to the vice president. They delivered gifts to Dawes in a giant paper-mache pipe, a nod to his affinity for smoking a Lyon pipe (he became so identified with it that it became known after as the Dawes pipe). The gifts included a copy of the Senate rules “shot full of holes,” a clever reference to Dawes’s much-publicized harangue against Senate procedures that he had delivered from the presiding officer’s chair earlier that year. At the 1927 dinner, the pages presented Dawes with a new set of rules they had written to give the vice president complete control over Senate debate. Another gift was a model of a yellow taxicab, to mark the day that Dawes slept peacefully at the Willard Hotel when he was needed to cast a critical tie-breaking vote. Dawes had been awakened and hopped into a cab to rush back to the Chamber only to find he was too late to cast a vote. A few years later, the pages presented Vice President Charles Curtis with a tool to maintain order in the Chamber: a giant paper-mache gavel. The pages informed Curtis that should a senator become disorderly, the gavel was “guaranteed to mash ’em flat.” In return, Curtis gave each page a silver dollar.9

The vice president’s annual Senate page Christmas dinner and the associated gift giving continued a few more years, but the nascent tradition came to an end in the 1930s. Part of the reason for its demise was the adoption in 1933 of the 20th Amendment to the Constitution, which moved the start of congressional sessions from December to January. With the Senate recessing by fall in the years that followed, neither the vice president nor the pages were on duty at the Capitol for the holiday season. By the 1960s, when Senate sessions were growing longer and often extending into December, both the page program and the vice presidency had undergone changes. Rather than employing local youngsters for multiple years, the page program began accepting high school students from around the country to serve one semester at a time. By this time, the vice president also spent less time at the Capitol. Assuming more executive duties, the vice president began presiding only on ceremonial occasions or when needed to break a tie vote. Once a cherished Senate tradition, the annual gift exchanges disappeared and became lost to the past.

Notes

1. Congressional Globe, 35th Cong., 1st sess., December 23, 1857, 156; Jacob R. Straus, "Federal Holidays: Evolution and Current Practices," Congressional Research Service, R41990, updated July 1, 2021; “Holiday Pressure Is Growing,” Washington Post, December 19, 1892, 6; “Around the Capitol,” Baltimore Sun, December 25, 1894, 2.

2. Isaac Bassett Papers, Box 20, Folder G, p. 180, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. [online version available through Archives Research Catalog (ARC Identifier 5423124, p. 22) at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5423124].

3. “Coal His Christmas Gift,” New York Times, December 25, 1902, 3.

4. “Christmas Celebration at the Federal Capital,” Atlanta Constitution, December 23, 1900, 18; “Senate Pages Christmas Gifts,” Washington Post, December 23, 1887, 2.

5. “Marshall Is Pages’ Host,” Washington Post, December 24, 1915, 4; “Coolidge Invites Pages,” New York Times, December 23, 1921, 12.

6. “Senators Remember Pages and Officials,” Washington Times, December 25, 1915, 6, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, accessed December 1, 2020, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1915-12-25/ed-1/seq-6/; “Senate Pages Receive Gifts,” Washington Evening Star, December 23, 1916, 10, Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1916-12-23/ed-1/seq-10/; Washington Evening Star, January 4, 1925, Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1925-01-04/ed-1/seq-85/; “Senate Chief Pages Get Christmas Gifts,” Washington Herald, December 25, 1915, 9, Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045433/1915-12-25/ed-1/seq-9/; "Donald J. Detwiler: Senate Page (1917–1918),” Oral History Interview, August 8, 1985, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C., available at https://www.senate.gov/about/oral-history/detwiler-donald-oral-history.htm.

7. “Pages in Senate Have Lost Santa Clause thru Promotion,” Atlanta Constitution, December 23, 1923, 16.

8. “Senate Pages Get Feast After All,” Boston Daily Globe, December 29, 1923, 7.

9. “Curtis Gets a Huge Gavel,” New York Times, December 25, 1930; “'Study Senators' Is Advice to Pages,” Washington Evening Star, December 25, 1929, 4, Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1929-12-25/ed-1/seq-4/ ; “Dawes Gives Christmas Party,” Washington Post, December 24, 1926, 4; “New Set of Rules Is Dawes’s Gift from Pages in Senate,” Hartford Courant, December 23, 1927, 10; “Senate Pages Turn the Tables on Dawes,” New York Times, December 24, 1926, 2.

|