On May 24, 1844, Samuel F. B. Morse achieved a historic triumph when he successfully transmitted a message over copper wire from the Senate wing of the U.S. Capitol to Baltimore, Maryland, the first long-distance demonstration of his electromagnetic telegraph. His invention would revolutionize communications in the United States and throughout the world.

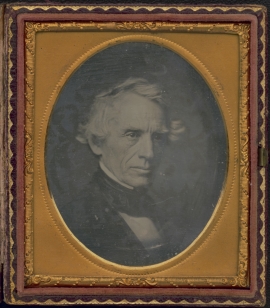

The son of famed preacher and geographer Jedidiah Morse—whose book The American Geography (1789) was a best-seller in the country for decades—Samuel Morse began his career as an artist. After graduating from Yale College in 1811, he went to London to study painting and returned to the United States in 1815 with hopes of earning public acclaim for his art. His first major painting, a now-famous depiction of the House of Representatives in session, was a commercial failure, leaving him to earn a meager living as a portrait painter. In 1824 he won the commission to paint a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette during his tour of America, and the painting launched him into the upper echelon of New York artists. In the 1830s, Morse went on to found and lead the National Academy of Design and became a professor at the University of the City of New-York (later known as New York University). He also became active in politics as chief spokesman for the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Native American Democratic Association. His career as a painter effectively ended in 1837, when he failed to win a commission for one of four monumental paintings to be added to the Capitol Rotunda, leaving him dejected and embarrassed.1

That same year, Morse’s interest in technology and invention set him on a new path. More than five years earlier, building on what others had learned in the fields of electricity and electromagnetism, Morse had conceived of transmitting messages using electrical current over wire and had built crude devices for sending and receiving these coded messages. In the fall of 1837, news about experiments in electrical telegraphs began to trickle into the United States from Europe. Upon learning this news, Morse quickly began to publicize his earlier work on the electric telegraph and identified himself as its inventor. Amid challenges to this claim from other inventors, and seeking to protect his rights in the invention, Morse reached out to his friend and Yale classmate Henry L. Ellsworth, who was Commissioner of Patents. Ellsworth provided him with a caveat, a document that preserved his claim of priority, while he prepared to apply for a patent.2

Not having expertise in the science of electricity, Morse partnered with a chemistry professor at the University of the City of New-York, Leonard Gale, to build a working telegraph, and in September 1837 the two men gave their first demonstration. Morse then turned to a former student and toolmaker, Alfred Vail, to assist with refining and producing his instruments. In December Morse submitted a proposal to Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury, who had been tasked by the House of Representatives with soliciting proposals for the construction of a telegraph system in the United States. All but one of the respondents presented plans for an optical telegraph—a series of towers with humans sending signals in semaphore to one another, a version of which had already been established in France. Morse was the lone respondent to propose an “electromagnetic telegraph,” with electrical signals sent over long distances by wire. Morse informed Woodbury that his device had sent a signal over 10 miles of spooled wire and that he “had no doubt of its effecting a similar result at any distance.”3

After demonstrations in New York and Philadelphia—in which Morse introduced the now famous code of dashes and dots that bears his name—he set up his equipment in the room of the House Committee on Commerce in the Capitol in February 1838 and gave a demonstration, explaining the technology to a group composed of members of Congress and President Martin Van Buren and his cabinet. In an era when investment funds were scarce and public support for national infrastructure was hotly debated, many inventors came to Congress looking for financial support. “It was not an uncommon thing for inventors of all kinds of outlandish and impractical machines to hang around the Capitol buttonholing every senator and member they could meet,” recalled Senate doorkeeper Isaac Bassett. The House Committee on Commerce, chaired by Francis O. J. Smith, asked Morse to submit a full report on his invention and, once received, recommended to the full House an appropriation of $30,000 to construct a 50-mile test line. Smith was so impressed by the potential of Morse’s telegraph that after losing his bid for reelection, he signed on as one of Morse’s partners.4

Unfortunately for Morse, the financial panic of 1837 had weakened political support for public investment in infrastructure projects, and over the next four years Congress took no action on the Commerce Committee’s bill. The news in 1842 that English telegraphers were seeking investors in the United States and that the Commerce Committee was considering funding a version of a French optical system (at a fraction of the cost of an electromagnetic system) set a fire under Morse, prompting him to finally take steps to acquire his U.S. patent and once again seek funding from Congress.5

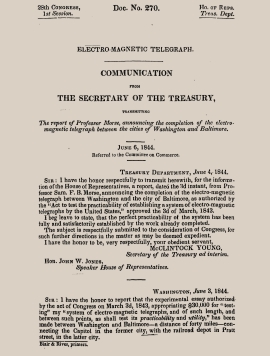

Morse began a correspondence with Representative William Boardman of Connecticut to get a petition on the floor of the House urging the Commerce Committee to explore establishing an electromagnetic telegraph system. With improved equipment, Morse began a new round of public demonstrations in New York and succeeded in passing a signal over 33 miles of wire. With the support of Boardman and Representative Charles Ferris of New York, he was able to resume his demonstrations in the Capitol, running wire from the Commerce Committee room across the length of the building to the Senate Naval Affairs Committee room. Ferris then submitted to the full House on behalf of the Commerce Committee a report stating that Morse’s apparatus was “decidedly superior to any now in use” and drafted legislation to appropriate the $30,000 to support the construction of a telegraph line “of such length, and between such points, as shall fully test its practicability and utility.” It passed the House and Senate and was signed into law on the last day of the Congress on March 3, 1843.6

Morse and his partners regrouped in Washington to begin the work on the test line. They chose Baltimore as the destination, with plans to install the wire along the route of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, a process delayed by numerous setbacks and frigid temperatures. In April 1844, Morse again set up his equipment in the Capitol, this time in a room on the north end of the Senate wing. One person who saw Morse’s apparatus in the Capitol later characterized the Senate room as “small and dingy” with a window “looking out onto Pennsylvania Avenue,” though the exact location remains unclear. As the wire reached farther east, Morse began sending out test messages, and on May 1, he gave the American public a first taste of what the electric telegraph could do. The Whig Party was holding a convention in Baltimore to nominate its presidential ticket. Alfred Vail, who had set up a station in Annapolis, 22 miles from Washington, intercepted the news of the balloting being carried by rail. He immediately transmitted it to Morse at the Capitol, bringing news of Henry Clay’s nomination to Washington a full hour before the train carrying the same message arrived.7

Finally, on May 24, with the wire stretching 38 miles between Washington and the railroad depot in Baltimore, Morse was prepared to officially open the telegraph line. In front of a small group of guests, he invited Annie Ellsworth, the daughter of the patent commissioner, to compose the first message. She chose the biblical phrase, “What hath God wrought.” Moments later, an identical message was returned from Vail in Baltimore, making the experiment a stunning success. Decades later, accounts stated that this first message was sent from the Old Supreme Court Chamber, and in 1944, to commemorate the centenary of the event, a plaque was placed outside the chamber identifying it as the site of the demonstration. Researchers have found no documentation, however, to suggest that Morse moved from the room in the Senate wing where he had set up his equipment, making it the most likely location from which the famous message was sent.8

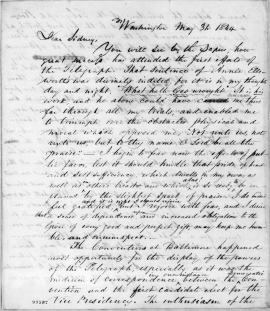

The May 24 demonstration was a private event and attracted little press attention. Days later, Morse demonstrated the revolution in communications to a wider audience. As the Democratic Convention met in Baltimore to select their presidential candidate, Vail telegraphed to the Capitol “with the rapidity of lightning” minute-by-minute updates on the balloting and the dramatic nomination of James K. Polk. President Pro Tempore Willie Mangum called the telegraph “a Miraculous triumph of Science” and recounted that a crowd of as many as a thousand eagerly awaited convention news outside of the Capitol. Morse wrote to his brother that the crowd “of some hundreds” called him to make an appearance at the window and offered three cheers to him and the telegraph. “Time and space have been completely annihilated,” declared one correspondent.9

Morse hoped to secure long-term federal funding to extend his line from Baltimore to New York and eventually to sell his invention to the government. Congress, however, appropriated only an additional $8,000 to keep the existing line in operation for another year under the direction of the Post Office, with Morse paid a salary as superintendent. Despite widespread awe at the technological achievement, lawmakers had trouble envisioning the telegraph as a useful, profitable venture. When renewal of the appropriation came up in 1845, Senator George McDuffie of South Carolina asked, “What is this telegraph to do? Would it transmit letters and newspapers?” Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri praised the technology and saw a future for it, but “wanted it to be called for by the commerce of the country, and pay its own expenses.” Congress funded the Washington-Baltimore line for only two more years, and in 1847 the Post Office leased it to private investors.10

Morse spent the next 20 years embroiled in legal fights as he, his partners and agents, and business rivals feuded over the rights and profits of establishing and growing a nationwide telegraph network. Despite Congress’s decision not to fund Morse’s work further and all the challenges that followed, private investment poured into the telegraph industry. Two decades after Morse’s Capitol demonstration, 100,000 miles of telegraph wire connected towns and cities across the United States, and Morse finally reaped the financial rewards of his invention. A few years later, the first transatlantic cable was laid between the United States and Europe. The telegraph revolutionized communications by sending news and information over vast distances almost instantaneously. It hastened westward expansion and spurred economic growth and investment in the United States, providing a handsome return on Congress’s initial investment.

Notes

1. Kenneth Silverman, Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F. B. Morse (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003), 3–20; “Samuel F. B. Morse,” National Gallery of Art, accessed April 11, 2024, https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1737.html.

4. Silverman, Lightning Man, 168–71; US Senate, Office of Senate Curator, Isaac Bassett Papers, Box 20, Folder B, p. 3, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Richard R. John, Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2010), 34–36.

7. John W. Kirk, “Historic Moments: The First News Message by Telegraph,” Scribner's Magazine 11 (May 1892): 652–56, https://todayinsci.com/Events/Telegram/TelegraphFirstNews.htm (accessed April 9, 2024).

9. Willie Mangum to Priestly H. Mangum, May 29, 1844, in Henry T. Shanks, ed., Papers of Willie Person Mangum, Vol. IV, 1844–1846 (North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 1955), 127–28; Morse to Sidney Morse, May 31, 1844, Samuel Morse Papers, Bound volume---15 January–8 June, Library of Congress Manuscript Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mmorse.017001/?sp=276&st=image&r=-0.083,0.058,1.106,0.66,0 (accessed April 9, 2024); “The Magnetic Telegraph,” Baltimore Sun, May 31, 1844, 2.