Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress. This year’s collection of treasures from the Senate Archives along with correspondence from manuscript collections tells the story of this very event—the Senate’s long journey to a quorum in the late winter and early spring of 1789.

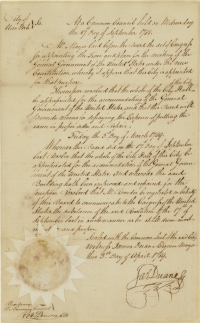

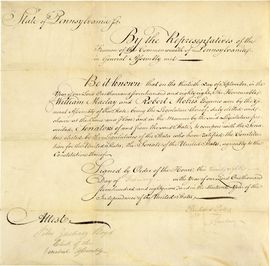

The Framers of the Constitution included a formula for its ratification. As stated in Article VII: “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution.” When the necessary ninth state—New Hampshire—ratified the Constitution on June 21, 1788, the Congress under the Articles of Confederation began the transition to form a new federal government. On September 13, that soon-to-expire Confederation Congress issued an ordinance giving states authority to elect their first senators and set the convening date for the First Federal Congress—March 4, 1789. As it turned out, that was the easy part.1

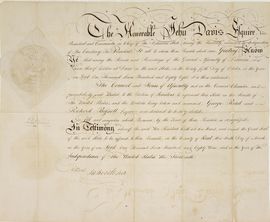

When the convening date arrived, the First Congress was to meet in the newly refurbished and renamed Federal Hall in New York City to count the electoral votes for president and vice president, inaugurate the winners, and proceed with its business. Writing to his wife that momentous day, Pennsylvania senator Robert Morris described the dramatic transition taking place in the city: “Last Night they fired 13 Canon [sic] from the Battery here over the Funeral of the Confederation & this Morning they Saluted the New Government with Eleven Cannon being one for each of the States that have adopted the Constitution,” he wrote. (Rhode Island and North Carolina had not yet ratified the Constitution.) “[R]inging of Bells & Crowds of People at the Meeting of Congress gave the air of a grand Festival to the 4th of March 1789 which no doubt will hereafter be Celebrated as a New Era in the Annals of the World.” The New York Daily Advertiser reported that “a general joy pervaded the whole city on this great, important and memorable event; every countenance testified a hope that under the auspices of the new government, commerce would again thrive … and peace and prosperity adorn our land.”2

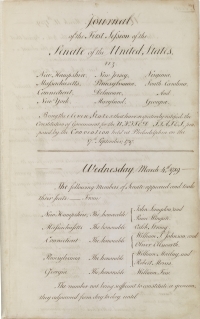

The exultation soon transitioned to disappointment, however, when both houses fell short of reaching the quorum required by the Constitution to conduct their business (30 representatives and 12 senators). Only 13 of the 59 representatives and only 8 of the 22 senators from the 11 states were present to offer their credentials (certificates of election) and be sworn in. "The number not being sufficient to constitute a quorum, they adjourned," reads the first entry in the Senate Journal.3

“We are in hopes these Numbers will Appear tomorrow,” an optimistic Morris wrote. News reports were likewise hopeful. “It is expected that a sufficient number to form a quorum will arrive this evening. Should that be the case the votes for President and Vice-President will be counted to-morrow,” the New York correspondent to the Massachusetts Centinel explained. In the subsequent days, the ongoing delay diminished such confident expectations and tested the patience of an anticipative country, including the punctual group of eight senators. Day after day, these senators appeared in the Senate Chamber only to be disappointed, harboring growing concerns of the government’s inability to operate.4

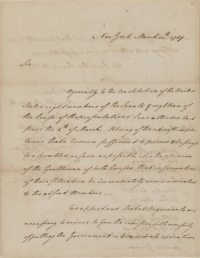

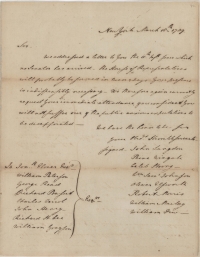

The image of a government paralyzed by absenteeism was all too familiar. The Confederation Congress had encountered similar problems, and in its final months, that legislature remained practically powerless to conduct business due to a lack of quorum. Thus, when only eight of the senators elected to the new federal government under the Constitution presented themselves on March 4, many feared a continuation of the old difficulty. "The members of the First Federal Congress who were on hand in New York on the appointed first day of the session were anxious to avoid any image of impotence caused by the lack of a quorum,” one historian explained. “They hoped that the new government could begin its work promptly, conveying an impression of the seriousness of their attention to duty to the expectant public." When a quorum failed to materialize over the next few days, those who had arrived pleaded with their missing colleagues in a letter. "We apprehend,” they wrote, “that no arguments are necessary to evince to you the indispensable necessity of putting the Government into immediate operation; and, therefore earnestly request, that you will be so obliging as to attend as soon as possible."5

Frustration and resentment grew as another week passed, and another, and still no quorum. “We earnestly request your immediate attendance,” they implored the absentees on March 18. Pennsylvania senator William Maclay complained in a letter to his friend Benjamin Rush, “I have never felt greater Mortification in my life[;] to be so long here with the Eyes of all the World on Us & to do nothing, is terrible.” In a later letter he added, “It is greatly to be lamented, That Men should pay so little regard to the important appointments that have devolved on them.” Members of the House of Representatives were likewise discouraged. “I am inclined to believe that the languor of the old Confederation is transfused into the members of the new Congress,” Massachusetts representative Fisher Ames wrote. “We lose credit, spirit, every thing. The public will forget the government before it is born.”6

The senators grew hopeful when Senator William Paterson of New Jersey appeared on March 19, followed soon thereafter by Richard Bassett of Delaware on the 21st and Jonathan Elmer of New Jersey on the 28th. Now 11 strong, they were still one man short of a quorum. Bassett earnestly wrote to his absent colleague, Delaware senator George Read, expressing concern that the House would reach a quorum before the Senate:

Where the Twelfth Member is to come from is not yet known, unless you can be prevailed on to Move forward—The Members of the Senate are very uneasy, and press me Exceedingly to urge the Necessity of your Making all Possible Dispatch in coming forward, as it is apprehended next week will bring forward a Sufficient Number of the other Branch to proceed, and they wish not to have the fault lain at our Door.7

Charles Thomson, who had been the secretary of the Continental Congress and was serving in a similar capacity during this interim period, also made a plea to Read, writing that he was “extremely mortified” that Read had not traveled to New York with Bassett, and expressing his fears that the delay would fuel opposition to the new government:

Those who feel for the honor and are solicitous for the happiness of this country are pained to the heart at the dilatory attendance of the members appointed to form the two houses while those who are averse to the new constitution and those who are unfriendly to the liberty & consequently to the happiness and prosperity of this country, exult at our languor & inattention to public concerns & flatter themselves that we shall continue as we have been for some time past the scoff of our enemies.…What must the world think of us?8

Despite the frustrations, blame, and admonishment, there were some well-founded and justifiable reasons for the delayed arrival of members, the most significant of these being the challenges of wintertime travel in the 18th century. The trip from Boston to New York City typically took six days, but during the winter, that journey could take two weeks or more. Senators navigated treacherous roads in wagons or sleighs and often were forced to seek refuge at nearby farms when conditions grew too dangerous. “There was no possibility of conveying [us] in February to new-york, by water or on wheels,” complained Massachusetts representative Elbridge Gerry. Senators from Maryland or Virginia endured weeks-long travel on horseback or in rickety coaches, braving cold and icy waters at five separate ferry crossings. Southerners, traveling mostly by sea, faced the greatest hazards of all. One southern member was delayed for weeks when his ship foundered off the Delaware coast.9

In addition to arduous weather and travel conditions, there were personal and political reasons for the delayed arrival of members of the new Congress. George Read, who finally arrived on April 13, was likely delayed due to sickness, as he later wrote that he had been unwell during this time. Correspondence from this period reveals that several others were delayed by illness, including Senator Elmer and Massachusetts senator Tristram Dalton. Politics also played a role. New York’s state legislature was deadlocked over candidates for months and did not send senators to Federal Hall until July 1789.10

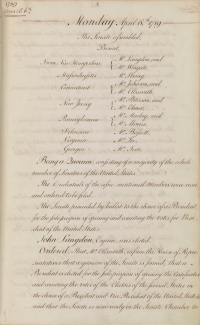

On April 1, the attending senators’ fears were realized when the House became the first of the two chambers to achieve a quorum. Five days later, on April 6, the necessary 12th senator finally arrived, Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee. The Senate then turned to the important business of helping to formalize the new national government by declaring the winner of its first presidential election. “Being a Quorum, consisting of a majority of the whole number of Senators of the United States. The Credentials of the afore mentioned members were read and ordered to be filed,” the Senate Journal reads. “The Senate proceeded by ballot to the choice of a President [pro tempore], for the sole purpose of opening and counting the votes for President of the United States.”11

Thankfully, the inauspicious beginning of the First Congress’s first session would not be repeated, as subsequent sessions saw some improvement in punctuality. In January 1790, at the start of the second session, a more experienced Senate reduced its convening delay to only two days. Finally, at the beginning of the third session in December 1790, the necessary quorum appeared on time and the Senate got down to business as planned. With the new government firmly established and transportation and infrastructure gradually improving, summoning a quorum would prove less of a challenge for future Congresses.

Notes

2. Robert Morris to Mary Morris, March 4, 1789, and New York Daily Advertiser, March 5, 1789, included in Charlene Bangs Bickford et al., eds., Correspondence: First Session, March–May 1789, vol. 15 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 15–16.

5. Charlene Bangs Bickford, “‘Public Attention Is Very Much Fixed on the Proceedings of the New Congress’: The First Federal Congress Organizes Itself,” in Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1999), 139; Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, March 11, 1789. Various Papers 1789–1982, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

6. Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, March 18, 1789. Various Papers 1789–1982, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; William Maclay to Benjamin Rush, March 19, 1789 and March 26, 1789, and Fisher Ames to George R. Minot, March 25, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:78, 126, 134.

10. William Thompson Read, Life and Correspondence of George Read: A Signer of the Declaration of Independence, with Notices of Some of His Contemporaries (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Company, 1870) 473; "New York’s First Senators: Late to Their Own Party," National Archives' Pieces of History blog, accessed March 26, 2024, https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2014/07/26/new-yorks-first-senators-late-to-their-own-party/.