| 202602 12Edward Brooke of Massachusetts—The Bridge Builder

February 12, 2026

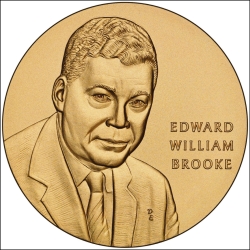

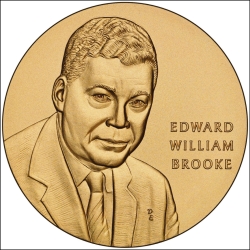

In 2009 former Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the first popularly elected African American senator, received the Congressional Gold Medal in recognition of his “pioneering accomplishments” in public service. During his two Senate terms, Brooke had been a pragmatic lawmaker, building bridges across party and racial lines to chart a course out of the nation’s segregated past, earning his place in the ranks of civil rights pioneers.

On October 28, 2009, former Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the first popularly elected African American senator, stood in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda to receive the Congressional Gold Medal. It was fitting that President Barack Obama, the first African American elected to the presidency, presented the medal to Brooke. Obama highlighted the improbability of a Black, Protestant Republican winning office in a state known for being white, Catholic, and Democratic. As Obama recalled, Brooke “ran for office, as he put it, to bring people together who had never been together before, and that he did.” As the only African American to serve in the Senate during the civil rights era, Brooke brought a unique set of experiences and perspectives to bear on some of the most politically charged issues of his time.1

Edward Brooke was born in the District of Columbia in 1919, to Helen, a homemaker, and Edward Jr., a lawyer with the U.S. Veteran’s Administration. Brooke grew up in the Brookland neighborhood of northeastern D.C., at a time when the city’s schools and public accommodations were segregated. He attended Dunbar High School, one of the best performing public high schools for African American students in the country. Following in his father’s footsteps, Brooke enrolled at Howard University, where he served in the school’s ROTC program, graduating in June 1941. Brooke entered the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant with the segregated, all-Black 366th Combat Infantry Regiment stationed at Fort Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts, on December 7, the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. 2

Brooke’s army service was an eye-opening, transformative experience. On the army base in Massachusetts, African American men were denied access to the pools, the exchange, and the officers’ club. “We were treated as second-class soldiers,” Brooke later recalled. Despite lacking any legal training, Brooke successfully defended Black enlisted men in military court—an experience that later led him to law school. In 1944 he sailed with his unit to Europe where he served in North Africa and in the campaign to liberate Italy. Brooke continued to encounter discrimination on base, this time in the form of racist tirades from his commanding officers. With some basic language training, Brooke quickly developed a fluency in Italian, a skill that proved useful in reconnaissance missions with Italian partisans. “My principal job,” he later explained, “was to map mine fields, supply roads, ammunition dumps, to locate concentration camps, and take prisoners for interrogation.” He never forgot the contrast between the freedom and dignity he felt when off base and the racism he experienced on base. Despite the challenges, Brooke earned the rank of captain and was awarded a Bronze Star in 1943 for “heroic or meritorious achievement or service.” While stationed in Italy, he met Remigia Ferrari-Scacco and the two were married in Boston in June 1947.3

Upon his return stateside, Brooke enrolled in Boston University School of Law, earning both a bachelor and a master of laws degree in 1948 and 1950, respectively. He built his own firm in Roxbury, a predominantly African American Boston neighborhood. Encouraged by friends to run for a seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the political neophyte (he did not cast his first vote until age 30) entered both the Republican and Democratic primaries for the house seat in 1950. He won the G.O.P. nomination but lost the general election. He ran again in 1952, with the same result. Stinging from two successive electoral defeats, Brooke continued to practice law while volunteering with various civic organizations, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.4

In 1960 state Republicans urged Brooke to run for secretary of the Commonwealth. He lost the race by a narrow margin to Democrat Kevin White, whose barely disguised racially charged slogan was, “Vote White.” Impressed by Brooke’s strong showing, Republican Governor John Volpe invited him to join his staff. Brooke declined but asked to be appointed chair of the Boston Finance Commission, a municipal watchdog. Volpe obliged, and Brooke transformed the moribund commission into an anti-corruption force, overseeing dozens of investigations, some of which resulted in the resignation of city officials. His oversight work helped him win election as state attorney general in 1962, flipping the office for the GOP. His victory made him the first African American attorney general in the nation and the highest-ranking African American in any state government at the time.5

Three years later, Brooke set his sights on national office. When Republican Senator Leverett Saltonstall announced his retirement in December 1965, Brooke jumped into the race for the open seat. His opponent was former Governor Endicott Peabody, who enjoyed the endorsement of Massachusetts’s popular senator, Democrat Edward “Ted” Kennedy. Brooke won handily, claiming 60 percent of votes cast. Members of the Black press hailed this historic victory as “the most exciting step forward for the Negro in politics” since Reconstruction.6

As an elected official in Massachusetts, Brooke had always been mindful that fewer than 10 percent of his constituents were Black. As attorney general, he had once declared, “I am not a civil rights leader and I don’t profess to be one. I can’t just serve the Negro cause. I’ve got to serve all the people of Massachusetts.” Even so, as the Senate’s only Black member during the peak of the civil rights movement, Brooke was committed to combating racial discrimination, noting in February 1967, “It’s not purely a Negro problem. It’s a social and economic problem—an American problem.”7

To tackle this problem, Brooke worked across party lines. He co-sponsored the Fair Housing Act with Democratic Senator Walter Mondale of Minnesota. Informed by Brooke’s work on the President’s Commission on Civil Disorders, the bill would prohibit housing discrimination in the sale, rental, or financing of housing nationwide. This would become the key provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Passing this ambitious civil rights bill, which faced strong opposition from southern senators, required patience and political acumen. At a time when it took two-thirds of senators present and voting to invoke cloture and overcome a filibuster, Brooke and Mondale painstakingly built a bipartisan coalition to pass the bill. After weeks of debate, and three failed cloture motions, the Senate finally invoked cloture and approved the bill. Brooke stood by the side of President Lyndon B. Johnson on April 11, 1968, as he signed it into law.8

Senator Brooke’s pragmatic approach to politics did not change after Republican Richard Nixon gained the presidency in 1969. While Brooke often supported the administration’s policies, including official recognition of China and nuclear arms limitation, he did not refrain from expressing his differences. He opposed three of the president’s six Supreme Court nominees, citing concerns over their stances on segregation. In November 1973, after the Senate Watergate Committee revealed that the Nixon administration had orchestrated a cover-up of its illegal campaign activities, Brooke became the first Republican senator to publicly call for the president’s resignation. “It has been like a nightmare,” Brooke said. “He might not be guilty of any impeachable offense “[but] because he has lost the confidence of the people of the country … he should step down, should, tender his resignation.”9

During the 1970s, much of Brooke’s legislative attention turned to protecting school desegregation efforts. Stating on national television that he was “deeply concerned about the lack of commitment to equal opportunities for all people,” Brooke charged that the White House neglected Black communities by failing to enforce school integration. Brooke was also central in defeating several antibusing bills initially passed by the House. In 1974 he successfully defeated the Holt amendment to an appropriations bill, introduced by Maryland Representative Marjorie Sewell Holt, that would have effectively ended the federal government’s role in school desegregation. That same year, Brooke helped quash an amendment introduced by Senator Edward Gurney (R-FL) that similarly would have ended busing. In 1975 Brooke reaffirmed his support for busing programs despite the political risk. “It’s not popular—certainly among my constituents. I know that,” he explained. “But, you know, I’ve always believed that those of us who serve in public life have a responsibility to inform and provide leadership for our constituents.”10

Brooke focused on other legislative initiatives as well, including regulating the tobacco industry, providing funding for cancer research programs, investigating connections between civil unrest and poverty, and advocating for a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion.11

Brooke easily won reelection in 1972 but faced a serious primary challenge in 1978, narrowly defeating conservative radio host and political newcomer Avi Nelson. Politically damaged by charges of financial improprieties, he was ultimately defeated by Democrat Paul Tsongas in the general election. Brooke retired from politics to practice law in Washington, D.C. In 2004 President George W. Bush awarded Brooke the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Four years later, Congress awarded him the Congressional Gold Medal, making him just the seventh senator to receive the award at the time. He died in January 2015.12

Edward Brooke did not define himself as a civil rights leader, but as a self-professed “creative Republican” and the Senate’s lone Black member, he sought ways to fight racial discrimination and improve opportunities for African Americans. Brooke was a pragmatic lawmaker, building bridges across party and racial lines to chart a course out of the nation’s segregated past, earning his place in the ranks of civil rights pioneers.13

Notes

1. Martin Kady II, “Brooke gets Congressional Gold Medal,” Politico, October 29, 2009, https://www.politico.com/story/2009/10/brooke-gets-congressional-gold-medal-028864.

2. “An Individual Who Happens to be a Negro,” Time, February 17, 1967.

3. Edward Brooke, Bridging the Divide (Rutgers University Press, 2007), 22.; John Henry Cutler, Ed Brooke; Biography of a Senator (Bobs Merrill, 1972), 27; “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE, Edward William, III,” History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, accessed February 3, 2026, https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/B/BROOKE,-Edward-William,-III-(B000871)/.

4. “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives; Brooke, Bridging, 64.

5. “An Individual,” Time; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives.

6. Edward W. Brooke, The Challenge of Change: Crisis in Our Two-Party System (Boston: Little, Brown, 1966); David S. Broder special, “Saltonstall is Quitting Senate,” New York Times, December 30, 1965; “Brooke Takes Office as Mass. Attorney General,” Chicago Defender, January 17, 1963, 4; “Brooke Takes a Giant Step into National Prominence,” Boston Globe, November 11, 1966, 18; “An Individual,” Time.

7. “Edward W. Brooke, Former U.S. Senator, Oaks Bluff Resident, Dies at 95,” Martha’s Vineyard Times, January 3, 2015, https://www.mvtimes.com/2015/01/03/edward-w-brooke-former-u-s-senator-oak-bluffs-resident-dies-95/; “An Individual,” Time.

8. Rigel C. Oliveri, “The Legislative Battle for the Fair Housing Act (1966–1968),” in Gregory D. Squires, ed., The Fight for Fair Housing: Causes, Consequences and Future Implications of the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act (New York: Routledge, 2017); “Congress Passes Rights Bill: Bars Bias in 80% of Housing,” Boston Globe, April 11, 1968, 1; “President Signs Civil Rights Bill: Pleads for Calm,” New York Times, April 12, 1968, 1; Civil Rights Act of 1968, Title VIII, Fair Housing, Public Law 90-284, 82 Stat. 73 (1968).

9. Brooke, Bridging, 191, 202, 203–4; “A Portrait of Racism,” Boston Globe, February 8, 1970, A25; “Brooke to Vote Against Nominee,” Hartford Courant, February 26, 1970, 5; “GOP Senator Brooke Asks Nixon to Quit,” Atlanta Constitution, November 5, 1973, 1A; “Carswell Disavows ’48 Speech Backing White Supremacy,” New York Times, January 22, 1970.

10. “Brooke Says Nixon Shuns Black Needs,” New York Times, March 12, 1970; “BROOKE,” History, Art & Archives; Richard D. Lyons, “Busing of Pupils Upheld in a Senate Vote of 47-46,” New York Times, May 16, 1974; Jason Sokol, “How a Young Joe Biden Turned Liberals Against Integration,” Politico, August 4, 2015, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/08/04/joe-biden-integration-school-busing-120968/.

11. Brooke, Bridging, 186, 216–7, 220.

12. Dane Morris Netherton, “Paul Tsongas and the Battles Over Energy and the Environment, 1974-80,” Ph.D. diss., Washington State University (May 2004): 130, 144.; “U.S. Senators Awarded the Congressional Gold Medal,” United States Senate, accessed February 3, 2026, https://www.senate.gov/senators/Senators_Congressional_Gold_Medal.htm.

13. Gary Orfield, “Senator Edward Brooke: A Personal Reflection,” The Civil Rights Project, accessed January 8, 2015, https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/senator-edward-brooke-a-personal-reflection-by-gary-orfield/; Sally Jacobs, “The Unfinished Chapter,” Globe Magazine, March 5, 2000, https://cache.boston.com/globe/magazine/2000/3-5/featurestory2.shtml.

|

| 202412 16When is a Senate First Truly a First?

December 16, 2024

In May 1971, newspapers heralded the end of a “boys-only” Senate page tradition with the appointment of three female pages. Senate historians have recently learned, however, that the Senate employed female pages at least as early as 1907. Emma Madeen served as a Senate riding page from June to December of that year, one of eight female riding pages who served between 1907 and 1926. The “discovery” of female riding pages in the early 20th century prompts a question: In an institution as old as the Senate, how can historians be certain that any event is a Senate “first”?

In May 1971 newspapers heralded the end of a long tradition when the Senate approved a resolution to allow the appointment of three female pages: Paulette Desell, Ellen McConnell, and Julie Price. “New Pages in Senate’s History: Girls,” announced the Washington Post. “Senate pages have always been boys, altho [sic] there is no regulation against the appointment of girls,” reported the Chicago Tribune.1

On one hand, the Tribune was correct. There had never been a rule prohibiting the appointment of female pages in the Senate. On the other hand, the story inaccurately identified Desell, McConnell, and Price as the first female Senate page appointments. While the efforts of these three teenagers who successfully petitioned for their appointments were historically significant at the time, Senate historians have recently learned that the Senate appointed female pages at least as early as 1907. Emma Madeen served as a Senate riding page from June to December of that year, one of eight female riding pages who served between 1907 and 1926. The “discovery” of female riding pages in the early 20th century prompts a question: In an institution as old as the Senate, how can historians be certain that any event is a Senate “first”?

The appointment of Senate pages is one of the Senate’s oldest traditions. It began in 1824 when 12-year-old James Tims, the relative of Senate employees, was listed in the compensation ledger as “boy—for attendance in the Senate room.” In 1837 Senate employment records showed the position of “page” to identify young messengers who provided support for Senate operations. The titles and responsibilities of pages evolved with the institution. There were “mail boys” who helped with mail delivery, “telegraph pages” who delivered outgoing messages between the Capitol’s telegraph offices, “telephone pages” who received telephone messages, and “riding pages” who carried messages from the Senate to executive departments and the White House on horseback.

Though it is difficult to pinpoint the precise date of the Senate’s first riding page appointment, Senate records indicate that they served during the Civil War. An 1862 Senate expense report includes payment for the rental of two saddle horses and two letter bags for use by “riding pages.” During the war, riding pages delivered messages throughout Washington on horseback, a fast and relatively safe way to navigate a city pockmarked by open sewers, crisscrossed by muddy roads, and infiltrated by Confederate spies. The position continued long after the war. In 1880 Senate ledgers recorded back pay for riding page Andrew F. Slade, the first known African American page to serve in the Senate, and the title of “riding page” was listed on the secretary of the Senate’s report of expenses that year.2

By the late 1880s, riding pages did not rely solely on horses to navigate the city. The Senate appointed Carl A. Loeffler in 1889 as a riding page under the patronage of Senator Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania. When he arrived at the Senate, Loeffler learned that riding pages had recently experimented with using the city’s horse car system to deliver their messages. Horse-drawn trolley cars, or “horse cars,” were a popular mode of transportation in the 1880s, with systems in many large American cities, including New York, Boston, and Washington, DC. Horse cars allowed passengers to avoid walking on crowded and sometimes muddy streets. But riding pages needed to quickly deliver messages throughout the city’s federal departments and return promptly to the Capitol, and horse cars, which made frequent stops, proved to be an impractical option. By the 1890s, riding pages had largely abandoned the use of horse cars and, with Senate permission, adopted bicycles—the latest transportation innovation. However, Senate pages continued to deliver messages and packages on horseback through the 1910s, likely until the Senate formally closed its horse stables in 1914, as recorded in the secretary of the Senate’s annual report that year. The duties of the Senate riding pages have evolved alongside the Senate’s own evolving roles and responsibilities. By the 1950s, riding pages delivered messages to executive agencies by car, for example, making the position best suited for adult Senate staff. And while the role of the riding page has continued into the 21st century, modern Senate riding pages have not been a part of the Senate’s formal page program.3

Senate riding pages enjoyed many perks. In 1899 the annual salary for a riding page was $912.50, a considerable sum when compared with the salary of a Senate document folder ($840), or a laborer ($720). In addition to good pay, these teenagers also traveled about the city independently, escaping the watchful eyes of supervising adults for extended periods of time. Occasionally, when a favorite Senate Chamber page aged out of that program (in the early 20th century, 12- to 16-year-olds were eligible for the position), they transitioned to the riding page program.4

Much of what we know about the riding page position comes from one of the Senate’s many official records, the secretary of the Senate’s report of expenses, published annually (and later biannually). This report provides historians with a snapshot of the Senate community at a moment in time. The 1896 report, for example, includes all purchases and salaries paid that year, including one oak rocker for the Committee on Claims ($5.50), and a salary of $1,440 paid to S. F. Tappau for service as a messenger to that committee. That same year, the report documents salaries for four riding pages: M. S. Railey, J. A. Thompson, C. A. Loeffler, and Frank Beall. These detailed reports include the names of staff, their titles, and salaries, but do not categorize individuals according to race, ethnicity, or gender. To identify women on Senate staff, historians rely upon other clues, especially “gendered” first names, and turn to other sources, including census records, personal diaries, and newspaper accounts, in hopes of confirming personal details. As the 1896 report suggests, lists of names can be ambiguous when initials, rather than full names, are published. Additionally, feminine names can be difficult to trace through the years. When women marry, they often take their spouse’s surname, complicating efforts to document their full Senate employment record.5

Yet, even with these incomplete records, Senate historians can challenge some long-standing accounts of notable Senate “firsts.” During the summer of 1907, according to the secretary of the Senate’s report, the Senate employed four riding pages: F. Beall , Parker Trent, Albertus Brown, and E. Madeen. A subsequent report reveals that the initial E stands for “Emma.” Madeen may have been the first female page appointment, but no newspapers reported Madeen’s appointment as extraordinary at the time. Unfortunately, no official records provide historians with clues about Madeen’s life in the Senate, on Capitol Hill, or in Washington, DC. How old was she and how did she secure this job? In late December 1907, Helen Taylor replaced Madeen as a riding page. A year later, Taylor was joined by a second female page, Rose Baringer, and others followed. In addition to Madeen, Taylor, and Baringer, Flora White, Henrietta Greeley, Lucy Murphy, Mildred Larrazolo, and Marguerite Frydell served as Senate riding pages between 1907 and 1926.6

Senators and staff in 1971 may be forgiven for forgetting these female riding pages, who left the Senate 45 years before the Senate reportedly ended the “boys only” page tradition. But even this timeline is more complicated than it seems. From 1951 to 1954, both party cloakrooms employed women as their “chief telephone pages.” Operating out of the private spaces reserved for senators at the rear of the chamber, these women (census records indicate that they were likely adults, rather than girls or teens) answered incoming calls from staff in the Senate office building and provided critical updates about members’ whereabouts and the day’s scheduled floor proceedings and debates. Before technology allowed for the internal broadcasting of floor speeches over so-called “squawk boxes,” the Senate’s telephone pages helped to ensure the institution’s smooth operations and, as a constant presence in the cloakrooms, were likely recognizable. In 1971, when the Senate reportedly ended its “boys only” tradition, at least a dozen senators who voted on that proposal had served in the Senate from 1951 to 1954—when they had likely encountered these female telephone pages.7

Was Emma Madeen the first female page appointment? The answer may be yes—that is, until Senate historians find evidence of an earlier one!

Notes

1. Angela Terrell, “Girl Pages Approved,” Washington Post, May 14, 1971; “Fight for Senate Girl Pages,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1971.

2. J. D. Dickey, Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, D.C. (Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2014); “General of the Army: The Bill Passes Restoring the Title,” Atlanta Constitution, June 2, 1888.

3. Carl Loeffler unpublished memoir, Senate Historical Office files; John H. White, Jr., Horsecars, Cable Cars and Omnibuses (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1974); Senate Committee on Government Operations, “Special Senate Investigation on Charges and Countercharges Involving: Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens, John G. Adams, H. Struve Hensel and Senator Joe McCarthy, Roy M. Cohn, and Francis P. Carr, Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations,” 83rd Cong., 2nd sess., Part 1, March 16 and April 22, 1954, 35; “Security Minded CIA is so Secure Senator Can’t Get Letter to Director, Page Turned Back at Barricade,” Washington Post, June 11, 1963.

4. “California Boy Coolidge’s Page,” Boston Daily Globe, February 13, 1922.

5. Annual Report of William R. Cox, Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 55-1, 55th Cong., 2nd sess., December 6, 1897, 7–8.

6. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Senate, S. Doc. 60-1, 60th Cong., 1st sess., December 4, 1907, 26.

7. “Robert G. Baker: Senate Page and Chief Telephone Page, 1943–1953; Secretary for the Majority, 1953–1963,” Oral History Interviews, June 1, 2009, to May 4, 2010, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C., 14–15.

|

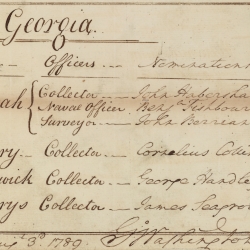

| 202404 06Treasures from the Senate Archives: The Long Journey to Quorum

April 06, 2024

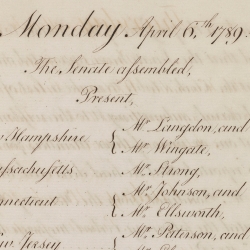

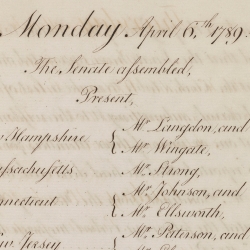

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress. This year’s collection of treasures from the Senate Archives along with correspondence from manuscript collections tells the story of this very event—the Senate’s long journey to a quorum in the late winter and early spring of 1789.

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress. This year’s collection of treasures from the Senate Archives along with correspondence from manuscript collections tells the story of this very event—the Senate’s long journey to a quorum in the late winter and early spring of 1789.

The Framers of the Constitution included a formula for its ratification. As stated in Article VII: “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution.” When the necessary ninth state—New Hampshire—ratified the Constitution on June 21, 1788, the Congress under the Articles of Confederation began the transition to form a new federal government. On September 13, that soon-to-expire Confederation Congress issued an ordinance giving states authority to elect their first senators and set the convening date for the First Federal Congress—March 4, 1789. As it turned out, that was the easy part.1

When the convening date arrived, the First Congress was to meet in the newly refurbished and renamed Federal Hall in New York City to count the electoral votes for president and vice president, inaugurate the winners, and proceed with its business. Writing to his wife that momentous day, Pennsylvania senator Robert Morris described the dramatic transition taking place in the city: “Last Night they fired 13 Canon [sic] from the Battery here over the Funeral of the Confederation & this Morning they Saluted the New Government with Eleven Cannon being one for each of the States that have adopted the Constitution,” he wrote. (Rhode Island and North Carolina had not yet ratified the Constitution.) “[R]inging of Bells & Crowds of People at the Meeting of Congress gave the air of a grand Festival to the 4th of March 1789 which no doubt will hereafter be Celebrated as a New Era in the Annals of the World.” The New York Daily Advertiser reported that “a general joy pervaded the whole city on this great, important and memorable event; every countenance testified a hope that under the auspices of the new government, commerce would again thrive … and peace and prosperity adorn our land.”2

The exultation soon transitioned to disappointment, however, when both houses fell short of reaching the quorum required by the Constitution to conduct their business (30 representatives and 12 senators). Only 13 of the 59 representatives and only 8 of the 22 senators from the 11 states were present to offer their credentials (certificates of election) and be sworn in. "The number not being sufficient to constitute a quorum, they adjourned," reads the first entry in the Senate Journal.3

“We are in hopes these Numbers will Appear tomorrow,” an optimistic Morris wrote. News reports were likewise hopeful. “It is expected that a sufficient number to form a quorum will arrive this evening. Should that be the case the votes for President and Vice-President will be counted to-morrow,” the New York correspondent to the Massachusetts Centinel explained. In the subsequent days, the ongoing delay diminished such confident expectations and tested the patience of an anticipative country, including the punctual group of eight senators. Day after day, these senators appeared in the Senate Chamber only to be disappointed, harboring growing concerns of the government’s inability to operate.4

The image of a government paralyzed by absenteeism was all too familiar. The Confederation Congress had encountered similar problems, and in its final months, that legislature remained practically powerless to conduct business due to a lack of quorum. Thus, when only eight of the senators elected to the new federal government under the Constitution presented themselves on March 4, many feared a continuation of the old difficulty. "The members of the First Federal Congress who were on hand in New York on the appointed first day of the session were anxious to avoid any image of impotence caused by the lack of a quorum,” one historian explained. “They hoped that the new government could begin its work promptly, conveying an impression of the seriousness of their attention to duty to the expectant public." When a quorum failed to materialize over the next few days, those who had arrived pleaded with their missing colleagues in a letter. "We apprehend,” they wrote, “that no arguments are necessary to evince to you the indispensable necessity of putting the Government into immediate operation; and, therefore earnestly request, that you will be so obliging as to attend as soon as possible."5

Frustration and resentment grew as another week passed, and another, and still no quorum. “We earnestly request your immediate attendance,” they implored the absentees on March 18. Pennsylvania senator William Maclay complained in a letter to his friend Benjamin Rush, “I have never felt greater Mortification in my life[;] to be so long here with the Eyes of all the World on Us & to do nothing, is terrible.” In a later letter he added, “It is greatly to be lamented, That Men should pay so little regard to the important appointments that have devolved on them.” Members of the House of Representatives were likewise discouraged. “I am inclined to believe that the languor of the old Confederation is transfused into the members of the new Congress,” Massachusetts representative Fisher Ames wrote. “We lose credit, spirit, every thing. The public will forget the government before it is born.”6

The senators grew hopeful when Senator William Paterson of New Jersey appeared on March 19, followed soon thereafter by Richard Bassett of Delaware on the 21st and Jonathan Elmer of New Jersey on the 28th. Now 11 strong, they were still one man short of a quorum. Bassett earnestly wrote to his absent colleague, Delaware senator George Read, expressing concern that the House would reach a quorum before the Senate:

Where the Twelfth Member is to come from is not yet known, unless you can be prevailed on to Move forward—The Members of the Senate are very uneasy, and press me Exceedingly to urge the Necessity of your Making all Possible Dispatch in coming forward, as it is apprehended next week will bring forward a Sufficient Number of the other Branch to proceed, and they wish not to have the fault lain at our Door.7

Charles Thomson, who had been the secretary of the Continental Congress and was serving in a similar capacity during this interim period, also made a plea to Read, writing that he was “extremely mortified” that Read had not traveled to New York with Bassett, and expressing his fears that the delay would fuel opposition to the new government:

Those who feel for the honor and are solicitous for the happiness of this country are pained to the heart at the dilatory attendance of the members appointed to form the two houses while those who are averse to the new constitution and those who are unfriendly to the liberty & consequently to the happiness and prosperity of this country, exult at our languor & inattention to public concerns & flatter themselves that we shall continue as we have been for some time past the scoff of our enemies.…What must the world think of us?8

Despite the frustrations, blame, and admonishment, there were some well-founded and justifiable reasons for the delayed arrival of members, the most significant of these being the challenges of wintertime travel in the 18th century. The trip from Boston to New York City typically took six days, but during the winter, that journey could take two weeks or more. Senators navigated treacherous roads in wagons or sleighs and often were forced to seek refuge at nearby farms when conditions grew too dangerous. “There was no possibility of conveying [us] in February to new-york, by water or on wheels,” complained Massachusetts representative Elbridge Gerry. Senators from Maryland or Virginia endured weeks-long travel on horseback or in rickety coaches, braving cold and icy waters at five separate ferry crossings. Southerners, traveling mostly by sea, faced the greatest hazards of all. One southern member was delayed for weeks when his ship foundered off the Delaware coast.9

In addition to arduous weather and travel conditions, there were personal and political reasons for the delayed arrival of members of the new Congress. George Read, who finally arrived on April 13, was likely delayed due to sickness, as he later wrote that he had been unwell during this time. Correspondence from this period reveals that several others were delayed by illness, including Senator Elmer and Massachusetts senator Tristram Dalton. Politics also played a role. New York’s state legislature was deadlocked over candidates for months and did not send senators to Federal Hall until July 1789.10

On April 1, the attending senators’ fears were realized when the House became the first of the two chambers to achieve a quorum. Five days later, on April 6, the necessary 12th senator finally arrived, Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee. The Senate then turned to the important business of helping to formalize the new national government by declaring the winner of its first presidential election. “Being a Quorum, consisting of a majority of the whole number of Senators of the United States. The Credentials of the afore mentioned members were read and ordered to be filed,” the Senate Journal reads. “The Senate proceeded by ballot to the choice of a President [pro tempore], for the sole purpose of opening and counting the votes for President of the United States.”11

Thankfully, the inauspicious beginning of the First Congress’s first session would not be repeated, as subsequent sessions saw some improvement in punctuality. In January 1790, at the start of the second session, a more experienced Senate reduced its convening delay to only two days. Finally, at the beginning of the third session in December 1790, the necessary quorum appeared on time and the Senate got down to business as planned. With the new government firmly established and transportation and infrastructure gradually improving, summoning a quorum would prove less of a challenge for future Congresses.

Notes

1. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904–37), 34:523, September 13, 1788.

2. Robert Morris to Mary Morris, March 4, 1789, and New York Daily Advertiser, March 5, 1789, included in Charlene Bangs Bickford et al., eds., Correspondence: First Session, March–May 1789, vol. 15 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 15–16.

3. Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., March 4, 1789.

4. Robert Morris to Mary Morris, March 4, 1789, and Massachusetts Centinel, March 14, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:15–17.

5. Charlene Bangs Bickford, “‘Public Attention Is Very Much Fixed on the Proceedings of the New Congress’: The First Federal Congress Organizes Itself,” in Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1999), 139; Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, March 11, 1789. Various Papers 1789–1982, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

6. Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, March 18, 1789. Various Papers 1789–1982, Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; William Maclay to Benjamin Rush, March 19, 1789 and March 26, 1789, and Fisher Ames to George R. Minot, March 25, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:78, 126, 134.

7. Richard Bassett to George Read, March 21, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:86.

8. Charles Thomson to George Read, March 21, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:90–91.

9. A good description of the hazards of travel to New York at this time is included Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:19–22; Elbridge Gerry to James Warren, March 22, 1789, included in Bickford, Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 15:92.

10. William Thompson Read, Life and Correspondence of George Read: A Signer of the Declaration of Independence, with Notices of Some of His Contemporaries (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Company, 1870) 473; "New York’s First Senators: Late to Their Own Party," National Archives' Pieces of History blog, accessed March 26, 2024, https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2014/07/26/new-yorks-first-senators-late-to-their-own-party/.

11. Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 1st sess., April 6, 1789.

|

| 202402 28Integrating Senate Spaces: Louis Lautier, Alice Dunnigan, Thomas Thornton and Christine McCreary

February 28, 2024

African American men and women have worked on Capitol Hill since Congress moved to the new capital in the District of Columbia in 1800. Black laborers, enslaved and free, helped to build the Capitol. They worked as messengers, groundskeepers, carpenters, and cafeteria workers. In the 20th century, as African Americans moved into professional positions, they began to challenge inequality in their workplaces. Years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 legally ended segregation, four courageous individuals demanded the integration of Senate spaces.

African American men and women have worked on Capitol Hill since Congress moved to the new capital in the District of Columbia in 1800. Black laborers, enslaved and free, helped to build the Capitol. In the 19th century, African Americans worked as messengers, groundskeepers, pages, carpenters, and cafeteria workers. In the 20th century, as they began to move into professional positions, they challenged the discriminatory practices that prevailed in their workplaces. Years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 legally ended segregation, four courageous individuals demanded the integration of Senate spaces.

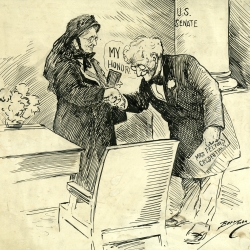

In January 1946, Louis Lautier, a correspondent for the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association, applied to the Senate Standing Committee of Correspondents for admission to the daily press gallery. In 1884 the Senate had made the Standing Committee, a group of elected members of the press gallery, responsible for credentialing congressional correspondents. Under Senate rules, the daily press gallery was open to correspondents “who represent daily newspapers or newspaper associations requiring telegraphic service.” Most African American papers were published weekly. A separate periodicals gallery served reporters of weekly magazines, not newspapers. Rules that seemingly were intended to prevent lobbyists from moonlighting as correspondents effectively made the Senate’s daily press gallery and the periodicals gallery off-limits to Black reporters. As Senate Historian Emeritus Donald Ritchie explains, “There [was] never a rule of the press gallery that says, ‘You have to be a white man,’ but the rules are written in such a way that that’s the only people who could get in.1

African American reporters had applied for admission on occasion despite these regulations, but their applications had all met the same fate—rejection. When rejecting Lautier’s application for admission in January 1946, the Standing Committee explained, “Inasmuch as your chief attention and your principal earned income is not obtained from daily telegraphic correspondence for a daily newspaper, as required under [Senate rules], you [are] not eligible.” Lautier then revised his application, noting that he was “jointly employed” by the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association, “with each organization paying half of my salary.” The Standing Committee stood by its initial decision, so Lautier appealed directly to the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, which had jurisdiction over the press galleries. The Rules Committee chairman, Democrat Harry Byrd of Virginia, did not intervene. Undeterred, Lautier resubmitted his application to the Standing Committee in November 1946.2

When the 80th Congress convened for its first session in January 1947, Republicans gained control of the Senate for the first time since 1933. One of the first orders of business facing the Senate was the seating of Senator Theodore Bilbo, a vocal white supremacist. In 1946 a Senate committee had investigated allegations by Black Mississippians that Bilbo had “conducted an aggressive and ruthless campaign” to deny Blacks the right to vote in the 1946 Democratic primary. A second, separate Senate inquiry had concluded that Bilbo had accepted “gifts, services, and political contributions” from war contractors whom he had assisted in securing government defense contracts. Lautier intended to cover the Senate debate, but without admittance to the press galleries, he was forced to wait in long lines for a seat in the public galleries, where Senate rules prohibited him from taking notes.3

Weeks later, on March 4, “after exhaustive deliberations and a personal hearing,” the Standing Committee again rejected Lautier’s application. Editorials in the national press urged the Standing Committee to reconsider its decision, and Lautier appealed to the new Rules Committee chairman, Senator C. Wayland “Curley” Brooks of Illinois. “Since the Standing Committee of Correspondents has acted arbitrarily in refusing me admission to the press galleries, and since under the interpretation of the rules Negro correspondents are barred solely because of their race or color, it appears that the Senate Rules Committee has the responsibility and duty to see that this gross discrimination against the Negro press is removed,” Lautier wrote.4

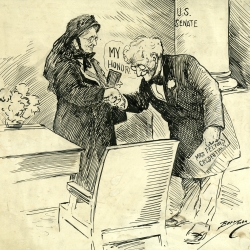

Senator Brooks, who had recently encountered separate allegations of racial discrimination in Senate facilities, readily agreed to investigate Lautier’s case. On March 18, 1947, Chairman Brooks convened a hearing to consider both Lautier’s application and the issue of discrimination in Senate dining facilities. “In the Capitol of the greatest free country in the world, we certainly should have no discrimination,” Brooks declared.5

The hearings first addressed Lautier’s application. Lautier testified that he met the qualifications for admittance to the daily press gallery under the existing rules. “I believe that I comply with the rules, if reasonably interpreted … because daily I gather news for the Atlanta Daily World.” While the rules had not been designed to “exclude Negro correspondents” from the press galleries “solely because of their race or color … that is the practical effect of the interpretation given the rules by the Standing Committee of Correspondents,” Lautier explained to committee members. Lautier described how the Atlanta Daily World and the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association rendered a vital service to African Americans by focusing on issues of particular significance to them. At a recent hearing to consider amending the cloture rule, for example, Louisiana senator John Overton had stated that “the Democratic South stands for white supremacy.” Overton’s statement, as well as debates about proposed changes to Senate rules and procedures, had been “inadequately reported by the white daily press,” Lautier explained. His readers relied upon Black correspondents to be “intelligently informed of what is going on in the Congress.”6

Testifying in defense of the decision to deny Lautier’s admission, the chairman of the Standing Committee, Griffing Bancroft of the Chicago Sun, maintained that race had not played a role in its decision making and recommended a rules revision “so that facilities could be provided for the weekly papers.” Brooks pressed Bancroft; couldn’t the situation be immediately resolved by admitting Lautier? That is not a long-term solution, Bancroft replied, because without revising the rules for admission, African American correspondents writing for weekly papers would continue to be denied admission to the daily press gallery and the periodicals gallery. Lautier believed that a rules change would not be required in his case, because “under a reasonable interpretation of [the current] rules I am entitled to admission.” Members of the Rules Committee agreed with Lautier and voted unanimously to approve his application for admission to the Senate daily press gallery. It was only a partial victory for Black correspondents, however, as it was not clear if Lautier’s admission had paved the way for other Black reporters.7

At the same time that Lautier was appealing the decision of the Standing Committee for credentials to the daily press gallery, Alice Dunnigan, the new Washington correspondent for the Associated Negro Press, had just arrived in the city to cover the Bilbo floor debate. Unaware of the Lautier case, Dunnigan submitted applications to the Standing Committee for admission to the daily press gallery and to the periodicals gallery, but she waited weeks with no answer. She called repeatedly to inquire about her application and made personal visits to the Capitol, “probably making a nuisance of [herself].” Even after Chairman Brooks’s hearing on Lautier’s application, Dunnigan still did not get an answer. After some investigation, Dunnigan learned that she faced another kind of discrimination. The founder and director of her news organization, Claude Barnett, had failed to provide a letter of recommendation in support of Dunnigan’s application, as required by the Standing Committee. When Dunnigan confronted Barnett about the issue, he explained, “For years, we have been trying to get a [Black] man accredited to the Capitol Galleries and have not succeeded. What makes you think that you—a woman—can accomplish this feat?” Dunnigan persisted, however, and Barnett eventually sent his letter to the Standing Committee, who promptly approved her application for admission to the daily gallery in June 1947. “My acceptance received widespread publicity,” Dunnigan later recalled, “and the Republican-controlled Congress received credit for opening the Capitol Press Galleries” to African American reporters.8

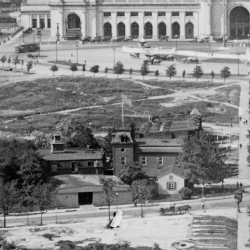

Chairman Brooks’s hearing on the Senate press galleries had a positive impact on integrating those Senate spaces, but the fight to integrate the Senate’s dining facilities took a bit longer. Brooks had appointed World War II army veteran Thomas N. Thornton, Jr., an African American, to a position as a mail carrier in the Senate post office on February 20, 1947. One day in early March, Thornton stopped at the luncheonette in the Senate Office Building (now the Russell Senate Office Building) and ordered a sandwich and coffee. A waitress asked Thornton to take his order to go, but he refused, sat down at a table, and ate his meal. Though Senate rules prohibited discrimination in Senate facilities, Thornton had violated a long-standing Senate practice of “whites only” dining facilities. Word of Thornton’s actions spread, and Washington Post syndicated columnist Drew Pearson reported that Sergeant at Arms Edward McGinnis had reprimanded Thornton and advised him not to eat again inside Senate dining facilities. During the March 1947 Rules Committee hearings about discrimination in Senate facilities, the Architect of the Capitol, David Lynn, whose responsibilities included the operation of Senate restaurants, assured Chairman Brooks that discrimination in Senate dining facilities would not be tolerated. “When this incident happened, it was purely a misunderstanding on the part of a new [restaurant] employee or it would never have happened,” reported the director of Senate dining facilities, D. W. Darling.9

Despite these assurances, de facto segregation in the Capitol’s dining rooms persisted for years. Not long after joining Senator Stuart Symington’s personal staff in 1953, Christine McCreary attempted to eat in the Senate cafeteria. When an anxious hostess reminded her that the cafeteria served “only … people who work in the Senate,” McCreary explained, patiently, that she worked for Senator Symington. The hostess demurred, then reluctantly invited McCreary to “take a seat anyplace you can find.” Diners gawked as McCreary passed through the serving line with tray in hand. “You could hear a pin drop,” she later recalled. Silently enduring the “snide remarks” of those who disapproved of her effort, McCreary remembered her first years of Senate service as “a lonesome time.” But she refused to give up. “I went back [to the cafeteria] the next day, and the next day, until finally they got used to seeing me coming.”10

As we commemorate Black History Month, let us acknowledge the perseverance and determination of members of the Senate community, including Lautier, Dunnigan, Thornton, and McCreary, and their remarkable courage in challenging the Senate’s long-standing discriminatory practices.

Notes

1. Donald A. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 109–110; “Donald Ritchie, Senate Historian 1976–2015,” Oral History Interviews, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.

2. “Credentials,” January 1946, Louis Lautier Case, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office: Senate Press Gallery, Standing Committee on Correspondents.

3. Special Committee to Investigate Senatorial Campaign Expenditures, Investigation of Senatorial Campaign Expenditures, 1946, S. Rep. 80-1, 80th Cong., 1st sess., January 3, 1947; Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, Investigation of the National Defense Program, Additional Report, Transactions Between Senator Theodore G. Bilbo and Various War Contractors, S. Rep. 79-110, Part 8, January 2, 1947, 79th Cong., 2nd sess., 2; Donald A. Ritchie, Reporting from Washington: The History of the Washington Press Corps (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 35.

4. Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery and Hearing on Reports of Discrimination in Admission to Senate Restaurants and Cafeterias, 80th Cong., 1st sess., March 18, 1947, 5–6, 47–52.

5. Ibid., 70.

6. Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 4, 10; Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Amending Senate Rule Relating to Cloture: Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Rules and Administration on S. Res. 25, 30, 32, and 39, 80th Cong., 1st sess., January 28, February 4, 11, 18, 1947.

7. Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 9, 38.

8. Alice Dunnigan, Alone Atop the Hill: The Autobiography of Alice Dunnigan, Pioneer of the National Black Press (Athens: The University Press of Georgia, 2015) 107–9, 110–12; Ritchie, Reporting From Washington, 39–40; “Credentials,” January 1947, Alice Dunnigan Case, included in the subject files of the Senate Historical Office: Senate Press Gallery, Standing Committee on Correspondents.

9. Kenneth O’Reilly, “The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson,” Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 17 (Autumn, 1997), 117–21; Rodney Dutcher, “Behind the Scenes in Washington,” Times-News, Hendersonville, N.C., March 3, 1934; Drew Pearson, “Color Bar in Senate Restaurant,” Washington Post, 8 Mar 1947, 9; Hearing on the Application of Louis R. Lautier for Admission to Senate Press Gallery, 61–64, 66; Report of the Secretary of the Senate, July 1, 1946, to January 3, 1947 and January 4, 1947, to June 30, 1947, S. Doc. 80-117, 80th Cong., 2nd sess., January 7, 1948, 260.

10. "Christine S. McCreary, Staff of Senator Stuart Symington, 1953–1977 and Senator John Glenn, 1977–1998," Oral History Interviews, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.

|

| 202303 08Enriching Senate Traditions: The First Women Guest Chaplains

March 08, 2023

The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857, and for more than 100 years, guest chaplains had all been men. That changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition.

The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. All Senate chaplains have been men of Christian denomination, although guest chaplains, some of whom have been women, have represented many of the world's major religious faiths.

The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857. That year, with many senators complaining that the position had become too politicized, the Senate chose not to elect a chaplain. Instead, senators invited guests from the Washington, D.C., area to serve as chaplain on a temporary basis. In 1859 the practice of electing a permanent chaplain resumed and has continued uninterrupted since that time, but the practice of inviting a guest chaplain to occasionally open a daily session also continued. While it is possible, and perhaps likely, that the Senate selected guest chaplains prior to 1857, surviving records from the period are insufficient to make that determination.

By the mid-20th century, guest chaplains were frequently offering the Senate’s opening prayer. Clergy visiting the nation’s capital often communicated their desire to serve as a guest chaplain to their home state senators who would nominate them for the role. In the 1950s, this practice became so popular among senators that Chaplain Frederick Brown Harris, who served nearly 25 years as Senate chaplain, complained to Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas that guest chaplains had replaced him 17 times over the course of just a few weeks. Leader Johnson assured Harris that he would ask senators “to restrict the number of visiting preachers,” but the frequency of the guests persisted.1

During the 1960s, Harris suffered from a series of medical issues and was less engaged in his official duties. Consequently, Harris’s unplanned absences prompted new problems for the Senate majority leader, now Mike Mansfield of Montana, whose staff was forced to arrange for last-minute guest chaplains. Infrequently, they called on senators to offer the prayer. Further irritating the majority leader, Harris unwittingly hosted guest chaplains who used the “forum to present their own particular litanies” and political viewpoints, thereby violating the Office of the Chaplain’s tradition of nonpartisan, nonpolitical service.2

Such issues prompted Senate leaders to reevaluate policies related to the appointment of guest chaplains. When Reverend Harris passed away in early 1969, Majority Leader Mansfield and Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois created an informal, bipartisan committee on the “State of the Senate Chaplain.” Upon concluding their study, the leaders informed Harris’s successor, Chaplain Edward L. R. Elson, of a policy change: “It would be our judgement that under ordinary circumstances a regular practice of inviting two guest chaplains per month is now in order.” Also, “In instances when you are ill or unavoidably absent, we would expect you to ask a brother clergyman to fill in temporarily in your stead.” The new policy was intended to standardize and bring order to the guest chaplain practice.3

For more than 100 years, guest chaplains had been men, but that changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition. A 1942 graduate of the Union Theological Seminary, Rowland became a minister in 1957, after the Presbyterian Church allowed for the ordination of women. She was an author and associate minister in Cincinnati, Ohio, before joining the United Presbyterian Board of Christian Education in Philadelphia, where she directed its educational loans and scholarships program. When Chaplain Elson invited her to lead the Senate’s opening prayer, Rowland recognized the historical significance of his offer. “It’s an honor to pray with and for such an august body,” she explained to the press. “I’m not unmindful of the women’s lib[eration] angle to my performance. But the prayer, like any other I have offered, is still to God. I’ve kept that in mind while I’ve been working on it.”4

Generally, the opening of the Senate’s daily session is sparsely attended. Six senators were present in the Chamber on July 8, 1971, for this historic event, including the Senate’s only woman senator, Margaret Chase Smith of Maine. Senate President pro tempore Allen Ellender of Louisiana called the Senate to order at noon, then introduced Dr. Rowland as “the very first lady ever to lead the Senate in prayer.” Rowland began:

O God, who daily bears the burden of our life, we pray for humility as well as forgiveness. As our nation plays its part in the life of the world, help us to know that all wisdom does not reside in us, and that other nations have the right to differ with us as to what is best for them.

Rowland later reflected on the event: “I’m pleased not for myself but for the fact the Senate has reached the point where they feel it is normal to invite a woman to do this.”5

But it wasn’t normal yet, and three years would pass before another woman delivered the Senate’s opening prayer. On July 17, 1974, Sister Joan Doyle, president of the Congregation of Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary headquartered in Dubuque, Iowa, became the second woman and the first Roman Catholic nun to offer the opening prayer in the Chamber. Her sponsor, Iowa senator Dick Clark, introduced her. At the conclusion of Doyle’s prayer, Minority Leader Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania praised her “gentler touch” for preparing senators to enter “into the brutal conflicts of the day.” Senator Margaret Chase Smith had retired in 1973, and Senator Clark reflected on the lack of women senators in the Chamber that day. “I hope it won’t be three more years before another woman is here, not only for the opening prayer, but as a member of the Senate.” It took more than five years, in fact, for the next woman senator to take a seat in the Chamber. On January 25, 1978, Muriel Humphrey was appointed to fill the seat left vacant when her husband, Senator Hubert Humphrey, passed away.6

Since 1974 other women have followed in the footsteps of Reverend Rowland and Sister Doyle, although the number of female guest chaplains remains small. In 2008 the Reverend Dr. Patricia Bryant Harris made history as the first African American woman to give the Senate’s opening prayer. “It had a lot of meaning to me personally, to be a part of that history,” Reverend Harris said in an interview. “That is now history as part of the Congressional Record.”7

The chaplain has been an integral part of the Senate community since the election of the first chaplain, Samuel Provoost, on April 25, 1789. Today, chaplains and guest chaplains, now men and women, deliver the opening prayer each day that the Senate is in session. As Senator Mary Landrieu of Louisiana remarked in 2012, "It is good that we take a moment before each legislative day begins in the Senate to still ourselves and ask for God's grace and guidance on the work that we have been called to do."8

Notes

1. Congressional Record, 91st Cong., 2nd sess., August 20, 1970, 29611.

2. “Chaplain Absent, Senator Gives Prayer,” Hartford Courant, September 20, 1963, 25B; “Senator Takes Chaplain’s Place,” Washington Post, Times Herald, September 2, 1964; Memorandum from Richard Baker to Mike Davidson, September 19, 1985, in the files of the Senate Historical Office.

3. Mike Mansfield and Everett Dirksen to Dr. Edward L. R. Elson, Chaplain, April 29, 1969, in the files of the Senate Historical Office.

4. “Barrier to Fall: Woman Will Lead the Senate in Prayer,” Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), July 4, 1971, A-10; “A Woman, Praying for the Senate,” Washington Post, July 9, 1971, B2.

5. Congressional Record, 92nd Cong., 1st sess., July 8, 1971, 23997; “Barrier to Fall: Woman Will Lead the Senate in Prayer.”

6. “Nun Gives Prayer in Senate,” Catholic Standard, July 25, 1974.

7. Nicole Gaudiano, “Del. Pastor makes history in U.S. Senate,” News Journal (Wilmington, DE), July 11, 2008, B1.

8. “At Sen. Landrieu’s Invitation, Louisiana Chaplain Offers Opening Prayer for U.S. Senate,” Targeted News Service, Feb. 28, 2012.

|

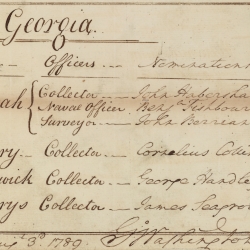

| 202211 21Rebecca Felton and One Hundred Years of Women Senators

November 21, 2022

On November 21, 1922, Rebecca Felton of Georgia took the oath of office, becoming the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate. Though her legacy has been tarnished by her racism, the significance of this milestone—now 100 years old—remains. Felton’s historic appointment opened the door for other women senators to follow. One hundred years later, 59 women have been elected or appointed to the Senate, and many more women have supported Senate operations as elected officers and staff.

On November 21, 1922, Rebecca Felton of Georgia took the oath of office, becoming the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate. Though her legacy has been tarnished by her racism, the significance of this milestone—now 100 years old—remains. Felton’s historic appointment opened the door for other women senators to follow. One hundred years later, 59 women have been elected or appointed to the Senate, and many more women have supported Senate operations as elected officers and staff.

Appointed to fill a vacant seat on October 3, 1922, Felton formally took the oath of office in the Senate Chamber on November 21 and served only 24 hours while the Senate was in session. For Felton, that historic day marked the culmination of a lifetime of political activism as a feminist, journalist, and suffragist. Like many of her contemporaries, however, Felton was also a white supremacist whose views on race both reflected and reinforced racial inequality for generations. Her complicated legacy sheds light on both the progressive and the reactionary politics that she influenced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born Rebecca Latimer in 1835, she was the daughter of a wealthy Georgia planter. She married Dr. William Felton in 1853, moving to his home near Cartersville. Although the state of Georgia prohibited women from owning property at that time, as the mistress of her husband’s plantation, Felton managed a household that included 50 enslaved people.

In 1860, as Civil War approached, the Feltons initially opposed the secession of Southern states from the Union, but like other white Southerners of their social class, they supported the Confederacy during the war to protect their “ownership of African slaves.” Felton later explained, “All I owned was invested in slaves.” She joined the local Ladies Aid Society to support the Confederate army. A physician and a preacher, William Felton tended Confederate soldiers at a nearby military camp, frequently leaving Rebecca alone to defend their property. Physical assault by marauding soldiers was a common wartime experience for rural women like Felton, and their trauma informed Felton’s political advocacy as she later fought for financial security and protection from sexual violence for all women.1

When the war concluded, the Feltons were emotionally depressed and financially destitute. They lost their farm and livelihood during the war and suffered the loss of two young children to wartime diseases. They founded a school, but politics soon came calling. After a report of the brutal sexual assault of a Black girl in a chain gang, Rebecca petitioned the Georgia state legislature to enhance protections for all female labor convicts—Black and white—and she would fight for prison reform for the remainder of her life. William pursued electoral politics, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Georgia state legislature. Felton participated in all aspects of her husband’s career, serving as his campaign manager and speechwriter, atypical roles for a woman in the 19th century. Political opponents criticized their unusual partnership. “We sincerely trust that the example set by Mrs. Felton will not be followed by southern ladies,” complained the Thomasville Times. “Let the dirty work in politics be confined to men.” By serving as her husband’s partner, and at times as his political surrogate, Felton helped to redefine the “traditional” role of southern white women.2

In the 1880s, Rebecca Felton broadened her activism, joining the temperance movement and emerging as a prominent and dynamic public speaker for the rights of poor, rural white women. A prolific and engaging writer, she co-founded a small newspaper in 1885 and later wrote a semi-weekly column for the Atlanta Journal. By the 1890s, Felton had emerged as a prominent public figure whose rousing speeches drew large crowds and whose columns and letters to the editor were widely distributed and debated nationwide. Felton used her influence to push for progressive policy reforms on behalf of white women and children, including universal public education, prison reform, better employment opportunities for women, and female suffrage.3

Felton’s views on race, however, were far from progressive, and throughout her life she held and perpetuated racist attitudes about African Americans. Decades after the Civil War, she continued to promote the myth of the happy enslaved person. She dehumanized Black men, calling them “debased, lustful brutes.” In her memoirs, published in 1919, Felton acknowledged that white supremacy served as an organizing principle for white southerners during and after the war. “The dread of negro insurrection and social equality with negroes at the ballot box held the Southern whites together in war or peace.” By the 1890s, many former Confederate states had adopted new constitutions to restrict African Americans’ civil rights, particularly voting rights. Prominent political figures, including Felton, inflamed racial tensions by promoting unfounded allegations of Black men assaulting white women. Such allegations fueled the heinous practice of lynching.4

In a widely reported speech in 1897, Felton criticized white men for their indifference to women’s rights and their failure to protect white women from assault, promoting her vision of equality for farm women. In the final moments of the speech, however, she pivoted to reactionary race politics: “As long as your politicians take the colored man into their embrace on election day…so long will lynching prevail.…If it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts,” she said, “then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary.” Although the purpose of her speech had been to promote the empowerment of white rural women, in the weeks and months that followed, it was Felton’s virulent support for lynching that was widely reported and used as justification for this barbaric practice.5

Shortly after her husband’s death in 1909, Felton joined the suffrage movement and canvassed the state to promote voting rights for women. Racism played a prominent role here as well, with many leading white suffragists insisting that extending voting rights to white women would help to dilute the voting power of Black men. When Felton testified before the all-male Georgia state legislature in 1914, for example, she asked: “Why can’t [women] help you make the laws the same as they help you run your homes and churches? I do not want to see a negro man walk to the polls and vote … while I myself [cannot].” In 1920 Felton and fellow suffragists celebrated the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which extended voting rights to many, though not all, women. Her suffrage work enhanced her popularity among newly enfranchised women voters in Georgia and beyond.6

In September 1922, when Georgia senator Thomas Watson died in office, he left a vacancy to be filled by gubernatorial appointment until the upcoming special election. Georgia governor (and former senator) Thomas Hardwick planned to appoint a “place-holder” and then run for that seat himself. Because he had opposed the Nineteenth Amendment, Hardwick feared newly enfranchised women would deny him the coveted Senate seat. On October 3, 1922, hoping to quell their opposition, Hardwick chose 87-year old Rebecca Latimer Felton of Cartersville for the historic appointment.

Hardwick ceremonially presented Felton with her appointment at Bartow County Courthouse on October 6. Women packed the courthouse, eager to show their support for the first woman senator. Because the Senate had adjourned sine die until December, and her replacement would be elected on November 7, Hardwick’s action was viewed as a symbolic attempt to gain women’s votes. Though Felton would receive a Senate salary and the administrative support of a secretary, as one newspaper reported, it was “only remotely possible” that she would appear on the Senate floor.7

Not content with a remote possibility, Felton’s allies launched an effort to have her seated in the Senate. Helen Longstreet, the widow of Georgia’s Confederate general James Longstreet, petitioned President Warren G. Harding in person on October 5, requesting that he call a special session before the November election so that Felton could be sworn in. Others followed Longstreet’s lead. “I voice the desire of multitudes of women voters,” explained one prominent suffragist in a letter to Harding, “who will shortly be approaching the polls.” Harding ignored the political pressure for a time, resisting calls for a special session. Meanwhile, on October 17, Governor Hardwick lost the Democratic primary to Judge Walter George, who won the general election on November 7. Felton now had an elected successor, but that didn’t halt the pressure to provide her the opportunity to take a Senate seat. Felton lobbied Harding to call Congress back for a special session as many of her supporters petitioned the president for action. On November 9, the president relented, announcing a special session to begin November 20 to consider several Republican legislative priorities. Attention again turned to Felton. Would she be seated?8

Less than a week before the special session was scheduled to convene, Georgia secretary of state S. G. McLendon, Felton’s political ally, declared that Walter George’s election likely would not be certified before the special session began. The ballots of 14 Georgia counties remained to be counted, he explained, and the state canvassing board had yet to be called to certify those results. According to state law, only the governor had the authority to convene the canvassing board, and Governor Hardwick was vacationing in New York. To resolve the situation, Hardwick returned to Georgia and convened the board, which promptly certified the election results. When the Senate convened on November 20, Senator-elect Walter George would be certified and ready to present his credentials. To many, Felton’s chances of taking the oath of office in an open session seemed to be dwindling.9

Undeterred, Felton personally asked George to delay presenting his credentials to the Senate. “I have no objections to interpose,” George astutely proclaimed at a press conference after their meeting. “The Senate is the exclusive judge of the eligibility of its members.… I will be glad to see the distinction come to [Felton], if the Senate can and will find a way to make this legally possible.” After George’s public announcement, Felton’s goal seemed within reach. She packed her bags and boarded a train to Washington, D.C. Both she and George would be present when the Senate convened for the special session. The Senate would decide her fate.10

On Monday, November 20, Felton arrived at the Senate early, her credentials tucked under her arm. Escorted into the Chamber by former Georgia senator Hoke Smith, she took a seat at an empty desk. Senators surrounded her, extending her a warm welcome. When the Senate convened at noon, it approved a resolution recognizing the death of her predecessor Thomas Watson and then—as was Senate custom—adjourned for the day. The question of Felton taking the oath would have to wait another 24 hours.

Felton again arrived early on November 21 and received a raucous ovation from visitors in the galleries as she took a seat at Watson’s vacant desk. After recessing for a joint session, the Senate reconvened, accepted the credentials of two new members, and then turned to deciding Felton’s case. Thomas Walsh of Montana addressed the chair. First describing the law that seemed to prevent Felton from being seated, Walsh then provided precedents in her favor. “I did not like to have it appear, if the lady is sworn in—as I have no doubt she is entitled to be sworn in—that the Senate … extend[ed] so grave a right to her as a favor, or as a mere matter of courtesy, or being moved by a spirit of gallantry,” he said, “but rather that the Senate, being fully advised about it, decided that she was entitled to take the oath.” Without objection, the clerk proceeded to read the certificate as presented by Felton, and Vice President Calvin Coolidge administered the oath of office shortly after noon.11

As a duly sworn senator, Felton answered one roll call and delivered a single speech. "When the women of the country come in and sit with you,” she told her Senate colleagues, “...you will get ability, you will get integrity..., you will get exalted patriotism, and you will get unstinted usefulness." She served for 24 hours before relinquishing the seat to Senator-elect Walter George. A gallery full of women erupted into cheers and applause as Senator Felton bade farewell.12

Following her appointment, Felton had predicted that women’s era had dawned, but women’s time in the Senate had begun to dawn even before Felton’s historic appointment. The Senate had already benefitted from a small but talented group of pioneering female staff, including Leona Wells, who joined the Senate's clerical staff in 1901 and became one of the first women to serve as lead clerk on a committee. By the early 1920s, women held half of the Senate’s committee staff positions. Today, women hold many of the most important and influential posts in the Senate, including secretary of the Senate and sergeant at arms.13

As Felton predicted, however, her historic appointment did pave the way for other trailblazing women senators. Hattie Caraway of Arkansas became the first woman to win election to the Senate in 1932 and subsequently the first to chair a committee. In 1938 Senator Gladys Pyle of South Dakota became the first Republican woman to serve in the Senate. Margaret Chase Smith of Maine took the oath of office in 1949, becoming the first woman to serve in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois, having prevailed in the general election of 1992, was the first African American woman senator. In 1995 Barbara Mikulski of Maryland set a milestone by becoming the first woman elected to Democratic Party leadership, and in 2000 Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas achieved that goal for the Republican Party. Other milestones followed. In 2013 Mazie Hirono of Hawaii became the first Asian and Pacific Islander woman to take the oath, while Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin became the first openly gay senator. The first Latina, Catherine Cortez Masto, joined the Senate in 2017. When Vice President Kamala Harris took the oath of office in 2021, she became the first woman to serve as president of the Senate and the first Asian American and African American to hold that position. On November 5, 2022, Senator Dianne Feinstein of California became the longest serving woman senator, with more than 30 years of Senate service. To date, 59 women have followed the trail blazed by Felton in 1922, with 24 serving in the 117th Congress. While historians continue to reckon with the troubling aspects of Felton’s life and career, her legacy as the first woman senator remains a significant milestone—now 100 years old—in the history of the Senate.

Notes

1. Rebecca Latimer Felton, Country Life in Georgia in the Days of My Youth (Atlanta, GA: Index Printing Co., 1919), 80, 86; Crystal N. Feimster, Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 7–36.

2. John E. Talmadge, Rebecca Latimer Felton: Nine Stormy Decades (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1960), 79; Feimster, Southern Horrors, 34–35.

3. Talmadge, Rebecca Latimer Felton, 125; LeeAnn Whites, “Rebecca Latimer Felton and the Wife’s Farm: The Class and Racial Politics of Gender Reform,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 76, No. 2 (Summer 1992): 372.