The chaplain of the U.S. Senate opens daily sessions with a prayer and provides spiritual counseling and guidance to the Senate community. An elected officer of the Senate, the chaplain is nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and nonsectarian. All Senate chaplains have been men of Christian denomination, although guest chaplains, some of whom have been women, have represented many of the world's major religious faiths.

The practice of inviting guest chaplains to deliver the Senate’s opening prayer dates to at least 1857. That year, with many senators complaining that the position had become too politicized, the Senate chose not to elect a chaplain. Instead, senators invited guests from the Washington, D.C., area to serve as chaplain on a temporary basis. In 1859 the practice of electing a permanent chaplain resumed and has continued uninterrupted since that time, but the practice of inviting a guest chaplain to occasionally open a daily session also continued. While it is possible, and perhaps likely, that the Senate selected guest chaplains prior to 1857, surviving records from the period are insufficient to make that determination.

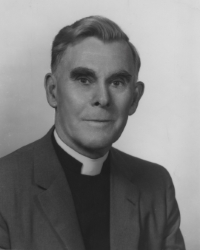

By the mid-20th century, guest chaplains were frequently offering the Senate’s opening prayer. Clergy visiting the nation’s capital often communicated their desire to serve as a guest chaplain to their home state senators who would nominate them for the role. In the 1950s, this practice became so popular among senators that Chaplain Frederick Brown Harris, who served nearly 25 years as Senate chaplain, complained to Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas that guest chaplains had replaced him 17 times over the course of just a few weeks. Leader Johnson assured Harris that he would ask senators “to restrict the number of visiting preachers,” but the frequency of the guests persisted.1

During the 1960s, Harris suffered from a series of medical issues and was less engaged in his official duties. Consequently, Harris’s unplanned absences prompted new problems for the Senate majority leader, now Mike Mansfield of Montana, whose staff was forced to arrange for last-minute guest chaplains. Infrequently, they called on senators to offer the prayer. Further irritating the majority leader, Harris unwittingly hosted guest chaplains who used the “forum to present their own particular litanies” and political viewpoints, thereby violating the Office of the Chaplain’s tradition of nonpartisan, nonpolitical service.2

Such issues prompted Senate leaders to reevaluate policies related to the appointment of guest chaplains. When Reverend Harris passed away in early 1969, Majority Leader Mansfield and Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois created an informal, bipartisan committee on the “State of the Senate Chaplain.” Upon concluding their study, the leaders informed Harris’s successor, Chaplain Edward L. R. Elson, of a policy change: “It would be our judgement that under ordinary circumstances a regular practice of inviting two guest chaplains per month is now in order.” Also, “In instances when you are ill or unavoidably absent, we would expect you to ask a brother clergyman to fill in temporarily in your stead.” The new policy was intended to standardize and bring order to the guest chaplain practice.3

For more than 100 years, guest chaplains had been men, but that changed in July 1971, when Reverend Dr. Wilmina M. Rowland of Philadelphia became the first woman to participate in this century-long tradition. A 1942 graduate of the Union Theological Seminary, Rowland became a minister in 1957, after the Presbyterian Church allowed for the ordination of women. She was an author and associate minister in Cincinnati, Ohio, before joining the United Presbyterian Board of Christian Education in Philadelphia, where she directed its educational loans and scholarships program. When Chaplain Elson invited her to lead the Senate’s opening prayer, Rowland recognized the historical significance of his offer. “It’s an honor to pray with and for such an august body,” she explained to the press. “I’m not unmindful of the women’s lib[eration] angle to my performance. But the prayer, like any other I have offered, is still to God. I’ve kept that in mind while I’ve been working on it.”4

Generally, the opening of the Senate’s daily session is sparsely attended. Six senators were present in the Chamber on July 8, 1971, for this historic event, including the Senate’s only woman senator, Margaret Chase Smith of Maine. Senate President pro tempore Allen Ellender of Louisiana called the Senate to order at noon, then introduced Dr. Rowland as “the very first lady ever to lead the Senate in prayer.” Rowland began:

O God, who daily bears the burden of our life, we pray for humility as well as forgiveness. As our nation plays its part in the life of the world, help us to know that all wisdom does not reside in us, and that other nations have the right to differ with us as to what is best for them.

Rowland later reflected on the event: “I’m pleased not for myself but for the fact the Senate has reached the point where they feel it is normal to invite a woman to do this.”5

But it wasn’t normal yet, and three years would pass before another woman delivered the Senate’s opening prayer. On July 17, 1974, Sister Joan Doyle, president of the Congregation of Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary headquartered in Dubuque, Iowa, became the second woman and the first Roman Catholic nun to offer the opening prayer in the Chamber. Her sponsor, Iowa senator Dick Clark, introduced her. At the conclusion of Doyle’s prayer, Minority Leader Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania praised her “gentler touch” for preparing senators to enter “into the brutal conflicts of the day.” Senator Margaret Chase Smith had retired in 1973, and Senator Clark reflected on the lack of women senators in the Chamber that day. “I hope it won’t be three more years before another woman is here, not only for the opening prayer, but as a member of the Senate.” It took more than five years, in fact, for the next woman senator to take a seat in the Chamber. On January 25, 1978, Muriel Humphrey was appointed to fill the seat left vacant when her husband, Senator Hubert Humphrey, passed away.6

Since 1974 other women have followed in the footsteps of Reverend Rowland and Sister Doyle, although the number of female guest chaplains remains small. In 2008 the Reverend Dr. Patricia Bryant Harris made history as the first African American woman to give the Senate’s opening prayer. “It had a lot of meaning to me personally, to be a part of that history,” Reverend Harris said in an interview. “That is now history as part of the Congressional Record.”7

The chaplain has been an integral part of the Senate community since the election of the first chaplain, Samuel Provoost, on April 25, 1789. Today, chaplains and guest chaplains, now men and women, deliver the opening prayer each day that the Senate is in session. As Senator Mary Landrieu of Louisiana remarked in 2012, "It is good that we take a moment before each legislative day begins in the Senate to still ourselves and ask for God's grace and guidance on the work that we have been called to do."8

Notes