| 202409 17Constitution Day 2024: The Senate’s Power of Advice and Consent on Nominations

September 17, 2024

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled this important responsibility. This selection of historical documents relates to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

To encourage Americans to learn more about the Constitution, Congress designated September 17—the date in 1787 when delegates to the federal convention signed the Constitution—as Constitution Day.

Throughout the summer of 1787, the framers of the Constitution debated where to place the power to make executive and judicial appointments. Eventually, they settled on the concept of a shared power—the president would make appointments with the “advice and consent” of the Senate. Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution provides that the president "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for.”

The president nominates all federal judges in the judicial branch and specified officers in cabinet-level departments, independent agencies, the military services, the Foreign Service, and uniformed civilian services, as well as U.S. attorneys and U.S. marshals. The vast majority are routinely confirmed, while a small but sometimes highly visible number of nominees fail to receive action or are rejected by the Senate. In its history, the Senate has confirmed 128 Supreme Court nominations and well over 500 cabinet nominations.

The following is a selection of historical documents related to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

John Adams’s Thoughts on Government, 1776

Written in the spring of 1776, John Adams’s Thoughts on Government was first drafted as a letter to North Carolina’s William Hooper, a fellow congressman in the Continental Congress, who had asked Adams for his views on forming a plan of government for North Carolina’s constitution. Adams developed several additional drafts for other colleagues in the following months, and the letter was ultimately published as a pamphlet. Adams’s plan called for three separate branches of government (including a bicameral legislature), which operated within a system of checks and balances, including a shared appointment power. Drawing from similar language in a 1691 Massachusetts’s colonial charter, and referencing a part of the legislative body he called the “Council,” Adams recommended that “The Governor, by and with and not without the Advice and Consent of the Council should nominate and appoint all Judges, Justices, and all other officers civil and military, who should have Commissions signed by the Governor.” Several years later, in 1780, Adams drew from his plan as he helped to write Massachusetts's constitution, which would include the shared appointment power and the phrase “advice and consent.”

In 1787, during the Constitutional Convention, the appointment or nomination clause split the delegates into two factions—those who wanted the executive to have the sole power of appointment, and those who wanted the national legislature, and more specifically the Senate, to have that responsibility. The latter faction followed precedents established by the Articles of Confederation and most of the state constitutions, which granted the legislature the power to make appointments, while the Massachusetts Constitution, with its divided appointment power, provided an alternative model, which was ultimately selected for the U.S. Constitution.

Report of the Grand Committee, September 4, 1787

After debating the appointment clause over the course of several weeks during the Constitutional Convention, the framers eventually settled on the concept of a shared power. Initially, the delegates granted the president the power to appoint the officers of the executive branch and, given that judges’ life-long terms would extend past the authority of any one president, allowed the Senate to appoint members of the judiciary. On September 4, 1787, however, as the proceedings of the convention were nearing conclusion, the Committee of Eleven (also known as the “Grand Committee”)—a special committee consisting of one delegate from each represented state that regularly met to resolve specific disagreements—reported an amended appointment clause. Unanimously adopted on September 7 and based on the Massachusetts constitutional model, which had been recommended earlier during the course of the debates by Massachusetts delegate Nathaniel Gorham, the clause provided that the president shall nominate and, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint the officers of the United States.

Nomination of Alexander Hamilton to be Secretary of the Treasury, 1789

On September 11, 1789, the new federal government under the Constitution took a large step forward. On that day, President George Washington sent his first cabinet nomination to the Senate for its advice and consent. Minutes later, perhaps even before the messenger returned to the president’s office, senators approved unanimously the appointment of Alexander Hamilton to be secretary of the treasury.

Hamilton’s place in history as the Senate’s first consideration and confirmation of a cabinet nominee is fitting as he had participated in the creation of this shared power. At the Constitutional Convention, and in the subsequent campaign to ensure the Constitution’s ratification, Hamilton was convinced that Senate confirmation of nominees would be a welcome check on the president and supported provisions that divided responsibility for appointing government officials between the president and the Senate. Defending the structure of the appointing power in Federalist 76, Hamilton wrote that the “cooperation of the Senate” in nominations “would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from State prejudice, from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity.”

Report of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary Concerning the Nomination of Joseph L. Smith to be Judge of the Superior Court of the Territory of Florida, 1822

The way in which the Senate has exercised its power of advice and consent on nominations has evolved over the course of its history. Before the 1860s, the Senate considered most presidential nominations without referring them to a committee for review or investigation. There were a few exceptions, however, including Joseph L. Smith (nominated by President James Monroe in 1822 to be judge of the Superior Court for the Territory of Florida), who was investigated by the Judiciary Committee, as shown by this report. “It was suggested to the committee that this gentleman had been a colonel in the Army of the United States, and had been lately cashiered upon charges derogatory to his moral character,” the report begins. Subsequently laid out in the report, the committee’s investigation revealed that charges against Smith were refuted by credible witnesses, and he was restored to his rank. “On a full view of all the facts and circumstances,” the report concluded, “the committee could see no objection that ought to operate against the appointment of Col. Smith, and therefore respectfully recommend…that the Senate do advise and consent to the appointment.” Persuaded by the findings of the committee, the full Senate confirmed Smith’s nomination.

Nomination Withdrawal, George H. Williams to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1874

In 1868 the Senate adopted rules to provide for more routine referral of nominations to "appropriate committees," but investigations of judicial nominees typically took place only in cases where the committee received credible allegations of wrongdoing on the part of a nominee. For example, in 1873 the Judiciary Committee, led by Chairman George Edmunds of Vermont, investigated allegations of financial misconduct against Attorney General George H. Williams, who had been nominated to be chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States by President Ulysses S. Grant. After an investigation, the committee informed the president that Williams would likely not be confirmed and Williams asked that his name be withdrawn.

The Senate’s formal order of Williams’s withdrawal begins with, “In Executive Session.” The confirmation of presidential nominations is one of the Senate’s executive (rather than legislative) constitutional duties. This task is therefore performed in executive session, separate from the Senate’s legislative proceedings. Prior to 1929, the Senate rules stipulated that nominations be debated in closed session. These closed executive proceedings were made open on occasion when the Senate voted to ”remove the injunction of secrecy,” and reports of these proceedings were often leaked to the press.

Senator Wilkinson Call to the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on the Nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida, 1890

In its first decade, the Senate established the practice of senatorial courtesy in which senators expected to be consulted on all nominees to federal posts within their states and senators deferred to the wishes of a colleague who objected to an individual nominated to serve in his or her state. If a president insisted on nominating an individual without consultation with or over the objections of a senator, senators merely had to announce in committee or before the full Senate that a nominee was “personally obnoxious” or “personally objectionable” to them without any further explanation. They could depend on the deference of Senate colleagues in rejecting the nominee. While the custom of senatorial courtesy was firmly established by the late 19th century, senatorial objections did not always doom the nomination, especially if a senator was of the opposing party from the president or the Senate majority. In 1890, with Senate Republicans in the majority and Republican Benjamin Harrison in the White House, Judiciary Committee chairman George Edmunds used this form letter to solicit the opinion of Florida Democratic senator Wilkinson Call about the nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida. “I do not consider him to be qualified either mentally or morally for the office of judge,” Call replied. Despite Call’s objection, and the objection of his fellow Florida senator Samuel Pasco (also a Democrat), Swayne’s nomination cleared the Senate.

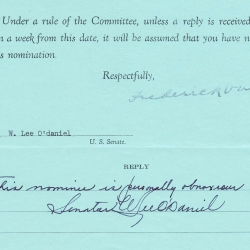

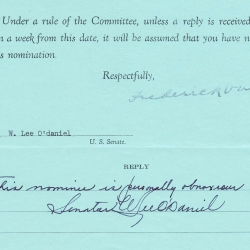

Blue Slip, Signed by Senator W. Lee O’Daniel, 1943

The Judiciary Committee formalized a version of senatorial courtesy through use of the “blue slip,” a blue sheet of paper on which a senator could register support for or opposition to a judicial nominee to serve in his or her state. The process has varied over the years, with different committee chairs giving varied weight to a negative or non-returned blue slip, but the system has endured, providing home-state senators the opportunity to be heard by the Judiciary Committee. During a nomination debate on the Senate floor in 1960, William Proxmire of Wisconsin called senatorial courtesy “the ultimate senatorial weapon,” a “nuclear warhead intercontinental ballistic missile of Senate nomination action.” While there have been changes to the rules and customs governing Senate advice and consent over the past half century—for example, senators no longer announce in the Senate Chamber that a nominee is “personally obnoxious” to them—individual senators continue to influence the nomination and confirmation process.

Hearings on the Nomination of Sandra Day O’Connor to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1981

During the 20th century, Senate committees hired staff to handle nominations and formalized procedures and practices for scrutinizing nominees. In 1939 Felix Frankfurter became the first nominee to appear before the Judiciary Committee to answer questions in a public hearing, and Dean Acheson became the first nominee for secretary of state to testify in open session before the Foreign Relations Committee 10 years later. By the 1950s, committees began routinely holding public hearings and requiring nominees to appear in person. By the 1990s, Judiciary Committee staff included an investigator who worked on nominations. In 1981 Sandra Day O’Connor of Arizona appeared before the Judiciary Committee as the first woman nominated to the serve on the Supreme Court. O’Connor’s nomination hearing was the first to be televised, and today all committee nomination hearings are broadcast or live-streamed on the Internet.

Today, committees have the option of reporting a nominee to the full Senate with a recommendation to approve ("reported favorably"), with a recommendation to not approve ("reported adversely"), or with no recommendation. Reporting adversely—sometimes because senatorial courtesy was not observed—has become rare. Since the 1970s, committees have on occasion, though still infrequently, voted not to report a nominee to the full Senate, effectively killing the nomination. More frequently, committees do not act on nominations that do not have majority support to move forward.

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution in 1787. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled its constitutional responsibility of advice and consent, playing a role both in the selection and confirmation of nominees.

|

| 202407 01100 Years Since Teapot Dome

July 01, 2024

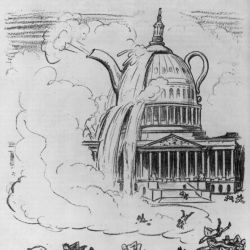

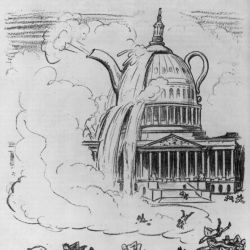

A century ago, in June 1924, the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys released a report, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, that outlined one of the worst breaches of the public trust in American history. The Senate investigation into the scandal, popularly known as Teapot Dome and led by Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, uncovered widespread corruption between government officials and powerful corporate interests. The inquiry serves as a powerful example of effective congressional oversight, highlighting the ability of lawmakers to expose wrongdoing to protect the public interest.

A century ago, in June 1924, the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys released a report, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, that outlined one of the worst breaches of the public trust in American history. The Senate investigation into the scandal, popularly known as Teapot Dome and led by Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, uncovered widespread corruption between government officials and powerful corporate interests. The inquiry serves as a powerful example of effective congressional oversight, highlighting the ability of lawmakers to expose wrongdoing to protect the public interest.

The seeds of the Teapot Dome scandal were planted in the first decade of the 20th century, when President Theodore Roosevelt and conservationists in Congress took steps to protect public lands from unlimited private exploitation. Concerned with ensuring the national government had access to energy resources and anticipating the conversion of the nation’s naval fleet from coal-burning to oil-burning power, Roosevelt instructed the U.S. Geological Survey to survey oil reservoirs beneath public lands. In 1909 President William Howard Taft responded to the Survey’s findings by signing an executive order withdrawing three million acres of public lands in California and Wyoming from private settlement and development and designating portions of these public lands in California, known as Elk Hills and Buena Vista, as naval oil reserves. In 1915 President Woodrow Wilson added a third naval oil reserve in Wyoming, named Teapot Dome after a sandstone rock formation that resembled a teapot. Congress by law in 1920 placed these reserves under the supervision of the secretary of the navy, who was given wide latitude “to conserve, develop, use, and operate the oil reserves” in the national interest.1

In the years after the reserves were created, the nation’s largest oil companies began plotting to obtain leases for drilling. The amount of oil in the reserves, and the money that could be made by extracting it, was staggering. Surveys estimated that the three reserves combined held 435 million barrels of oil, almost equal to the total amount of oil that had been produced in the country to that point. Extracted, those resources were estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, at least a billion in today’s dollars.2

In 1921 Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall was also keenly interested in the reserves. Fall was a former gold and silver prospector and attorney who had been elected to serve as one of New Mexico’s first senators in 1912. Known for his volatile personality and his frontiersman ways—he reportedly often carried a six-shooter pistol—Fall enjoyed the support of prominent industrialists who had helped finance his 1918 re-election campaign and provided backing for Fall’s purchase of a prominent Albuquerque newspaper. In the Senate, Fall became friends with fellow Republican senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio (who had joined the Senate in 1915), the two bonding over whiskey and poker games—then a popular Washington pastime. When Harding was elected president in 1920, he nominated Fall to be his secretary of the interior. Fall had plans to open the nation’s public lands to private development, and he persuaded the president to place the naval reserves under his control. On May 31, 1921, Harding signed an executive order transferring control of the naval reserves from the Navy Department to the Interior Department.3

Rumors swirled for months about Fall’s plans to develop the reserves. On April 12, 1922, Fall offered to his friend Harry F. Sinclair, the head of Sinclair Oil, an exclusive, no-bid lease for the Teapot Dome oil reserves. Intending to keep the deal a secret, Fall locked the contract in his desk and instructed the assistant secretary to tell no one about it. But intrepid reporters soon uncovered the story. On April 14, 1922, the Wall Street Journal ran a front-page exposé detailing the sweetheart deal. The Denver Post was not far behind, offering details about what it called “one of the baldest public land-grabs in history.”4

Independent oil producers saw the press coverage and, angry at not having had an opportunity to bid on the leases, complained to Wyoming Democratic senator John B. Kendrick about the secret negotiations of the Teapot Dome deal. When Kendrick inquired about the details of the lease from the Interior Department, Fall’s subordinates gave him the runaround. On April 15, Kendrick introduced a resolution in the Senate instructing the secretaries of the interior and the navy to inform the Senate about any ongoing negotiations for leases on Teapot Dome. Now under intense pressure, Fall released a statement to the press on April 18 announcing the Teapot Dome lease and disclosing the impending completion of another lease for the Elk Hills reserve to oil baron Edward Doheny and his Pan-American Oil Company. On April 20, Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, a progressive Republican and a leading conservationist in the Senate, introduced a resolution demanding from the Interior Department all documents relating to the negotiation and execution of leases on the naval oil reserves. The Senate amended the resolution to authorize the Committee on Public Lands and Surveys to conduct a full-scale investigation and approved it by unanimous vote (with 38 senators not voting) a week later.5

In early June, Fall submitted to President Harding a 75-page report and thousands of supporting documents detailing the history of the naval oil reserves and the geological data that Fall claimed justified the leases. Harding sent the report to the Senate with a memo stating that all policies regarding the reserves had been reviewed by him and “at all times had my entire approval.”6

The Teapot Dome investigation was slow to get off the ground. The first challenge was getting someone to lead it. While La Follette had been the driving force to authorize the inquiry, he was not a member of the Committee on Public Lands. The Republican chair of the committee was Reed Smoot of Utah, a conservative who was not enthusiastic about pursuing an investigation that could be politically damaging for his party. John Kendrick served on the Public Lands Committee but did not want to take on the task. La Follette and Kendrick persuaded Democrat Thomas Walsh of Montana to lead the investigation.

The son of Irish Catholic immigrants, Walsh had been an attorney in Helena, Montana, before becoming a powerful force in the state’s Democratic Party. Elected to the Senate in 1912, Walsh had a reputation as an able lawyer and a progressive willing to take on the powerful mining interests in his state. Walsh was the most junior member of the minority party on the committee, but the ranking Democrat was leaving the Senate after 1922, and La Follette and Kendrick opted to bypass the other more senior Democrats. Walsh was not a conservationist and had, to that point, been a supporter of opening up public lands—and Native American reservations—for resource exploitation. He was initially reluctant to commit to the investigation, but after some prodding from fellow Montana Democrat Burton K. Wheeler, he agreed in June 1922 to wade in and began reviewing the mountain of documents submitted by Fall.7

Walsh worked through the evidence methodically throughout the summer and fall of 1922, and by early 1923, he began to suspect that Fall had engaged in misconduct. In February 1923, with the Senate set to adjourn in March, the Public Lands Committee set a hearing date for October, a little more than a month before the 68th Congress would convene in December. By the time Walsh returned to Washington in September to begin preparing for the hearing, Albert Fall had resigned from the cabinet to go work for Sinclair, President Harding had died of a heart attack, and Vice President Calvin Coolidge had become president.8

When the hearings began on October 23, 1923, the main question facing the committee was whether Albert Fall was justified in secretly leasing the naval reserves without competitive bidding. Chairman Smoot called the committee to order and then turned over the proceedings to Walsh, who took the lead in questioning witnesses. In the opening round of questioning, Walsh challenged Fall on the legality of Harding transferring control over the naval reserves to him as secretary of the interior and argued that Congress had clearly intended for the secretary of the navy to be the steward of its oil. Fall contended that the president was in his rights to give him responsibility over the reserves. He defended his quick action in granting leases as necessary to prevent the reserves from being depleted by drainage—the intentional depletion of reserves by adjacent landowners. Reports from the Bureau of Mines had indicated that drainage was not a concern, but geologists hired by the committee at the behest of Chairman Smoot disagreed, claiming that the reserves were draining at a rapid rate and that only 25 million barrels of oil remained. Under questioning, Fall defended his selection of Sinclair as a sound business decision and the deal’s secrecy as a matter of national security. Smoot opined that “if the reports of the experts are accepted, the theory that the government made a mistake in leasing this reserve has been exploded.”9

Walsh had other sources, however, that opened up new avenues of investigation. Journalists from Denver and New Mexico—including Carl Magee, who had purchased Fall’s newspaper from him in 1920—told Walsh about a suspicious, abrupt change in Fall’s personal finances. Brought before the committee on November 30, Magee testified that Fall had been cash-poor in 1921 and a decade in arrears on the property taxes of his dilapidated New Mexico ranch. But in June 1922 Fall, suddenly flush with cash, paid his back taxes, purchased neighboring properties, and made substantial improvements to his previously rundown ranch. The burning question became, where did Fall get all of this money?10

By the time Walsh completed his questioning of witnesses in January 1924, he had uncovered suspicious payments made to Fall. Harry Sinclair gave Fall $269,000 in Liberty Bonds and cash a month after signing the Teapot Dome lease. Edward Doheny, to whom Fall awarded the Elk Hills reserve lease, testified that he instructed his son to deliver $100,000 (well over $1 million in today’s money) in cash to Fall “in a little brown satchel,” allegedly as a loan, but one that Fall had lied about and tried to conceal from Walsh and the committee. In a closed committee meeting, Walsh informed his colleagues that he would be introducing a resolution directing the president to appoint a special counsel to bring civil suits to cancel the naval reserve leases and to pursue criminal charges connected to awarding the leases. Republican Irvine Lenroot, now chair of the Public Lands Committee, informed President Coolidge of Walsh’s intentions and urged him to get out in front of the news. On January 27 Coolidge announced his intent to appoint counsel and file charges, and a few days later the Senate passed Walsh’s resolution.11

Walsh was not done with his investigation, however. What had begun in late 1923 as a quiet set of hearings in a small committee room soon became a public sensation with audiences packed into the spacious Caucus Room on the third floor of the Senate Office Building. Walsh recalled Fall to face more questioning, but Fall delayed, claiming ill health. When he finally returned on February 2, 1924, Fall refused to answer any additional questions, claiming his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself and further arguing that the imminent appointment of special prosecutors ended the committee’s authority over the case. When Sinclair came back for more questioning in March, he refused to answer questions as well, though he didn’t bother to cite his Fifth Amendment rights. “There is nothing in any of the facts or circumstances of the lease of Teapot Dome which does or can incriminate me,” he stated. The Senate referred contempt charges against both Fall and Sinclair to the District of Columbia courts.12

The Public Lands Committee concluded its hearings in May 1924, and a bipartisan majority issued its final report in June, signed by Edwin Ladd of North Dakota, who had become committee chair in March. Some senators and representatives, particularly Democrats, criticized the report for its lack of drama and its failure to draw conclusions about the corrupting influence of oil interests in government. Still, the report included additional evidence of corruption, including Sinclair’s payments to buy off rival claimants to the reserves, as well as a $1 million payment to newspaper publishers in exchange for their silence when they discovered the shady circumstances surrounding the Teapot Dome lease.13

The committee noted “rumors” of a broader conspiracy on the part of prominent oil companies to place Harding in the White House and Fall in the Interior Department for the very purpose of exploiting natural resources on public lands but concluded only that “the evidence failed to establish the existence of such a conspiracy.” Five Republicans on the committee, led by Smoot, issued a minority report complaining that the majority had not given them time to review the report and all the supporting evidence. In January 1925, a minority of the committee issued a more substantive report defending many aspects of the Harding administration’s handling of the naval reserves and criticizing Walsh for dedicating space in the report to what it saw as baseless rumors about political conspiracies. Historians who have dug into the scandal have since given these theories more credence.14

Civil and criminal litigation involving the oil reserve leases dragged on for the next six years, with several cases going before the Supreme Court. In the end, the government proved that the leases had been illegally obtained and successfully regained control of the naval reserves. Fall was found guilty of accepting a bribe from Sinclair and sentenced to a year in prison, the first cabinet official in U.S. history to be convicted of a felony. Juries acquitted Sinclair and Doheny on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government, however. Sinclair served prison time for contempt of court—he was found guilty of attempting to intimidate the jury in his criminal trial—and contempt of Congress. The Supreme Court heard his appeal, upheld his conviction, and recognized the Senate’s investigatory power and its authority to compel testimony from witnesses. In another contempt case arising out of a related investigation into Harding administration corruption, the Court held in the McGrain V. Daugherty decision, “We are of opinion that the power of inquiry—with process to enforce it, is an essential and appropriate auxiliary of the legislative function.”15

The Teapot Dome scandal cast a long shadow over American politics, for decades serving as a symbol of the highest form of government corruption. Lawmakers investigating charges of corruption in the decades that followed the scandal would inevitably make the comparison, warning the public that they may find evidence of “another Teapot Dome” or something “worse than Teapot Dome.” In 1950, commenting on the development of the western United States, President Harry Truman stated, “The name Teapot Dome stands as an everlasting symbol of the greed and privilege that underlay one philosophy about the West.” In 1973, as Watergate coverage flooded the national media, some reporters called it “the new Teapot Dome.” “For half a century, [Teapot Dome] has, for many Americans, represented the quintessence of corruption in government,” wrote one correspondent. “Now Teapot Dome has been shoved aside by contemporary events.”16

For the Senate, the Teapot Dome investigation firmly established the authority of Congress to question the executive branch and demand information about its operations. Senator Walsh’s diligent and tenacious search for the truth uncovered corruption and held the government accountable to the people it serves, setting a standard for future Senate investigations to emulate.

Notes

1. Hasia Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” in Congress Investigates: A Critical and Documentary History, vol. 1, eds. Roger Bruns, David Hostetter, and Raymond Smock (Byrd Center for Legislative Studies, 2011), 460; Laston McCartney, The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Bought the Harding Whitehouse and Tried to Steal the Country (New York: Random House, 2019), 28–29, 96.

2. Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves: Hearings Pursuant to S. Res. 282, S. Res. 294, and S. Res. 434, 68th Cong., October 31, 1923, 678. Experts of the time disagreed as to how much oil was held in the reserves. The Bureau of Mines estimated that Teapot Dome held 135 million barrels of oil, for example, but geologists employed by the Committee on Public Lands estimated it at only 12 to 26 million. These estimates turned out to be very low. The Elk Hills reserve alone has yielded more than a billion barrels of oil in the century since. “Elk Hills Is Source of Controversy,” New York Times, April 1, 1975, 10.

3. David Hodges Stratton, Tempest Over Teapot Dome: The Story of Albert B. Fall (Tulsa: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 148–49; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 31–35, 65–67.

4. Quoted in McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 127.

5. S. Res. 277, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 15, 1922; S. Res. 282, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 29, 1922; Congressional Record, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 29, 1922, 6092–97.

6. Naval Reserve Oil Leases, Message from the President of the United States, S. Doc. 67-210, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., June 8, 1922.

7. J. Leonard Bates, Senator Thomas J. Walsh: Law and Public Affairs from TR to FDR (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 201–11; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 160.

8. Bates, Senator Thomas J. Walsh, 210–11.

9. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, October 23, 24, 1923, 175–282; “Experts Uphold Teapot Dome Lease,” New York Times, October 23, 1923, 23, quoted in McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 171.

10. Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” 464; Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, November 30, 1923, 830–43.

11. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, January 24, 1924, 1772; Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” 466–68; Joint Resolution Directing the President to institute and prosecute suits to cancel certain leases of oil lands and incidental contracts, and for other purposes, Public Resolution 68–4, 68th Cong., 1st sess., February 3, 1924, 43 Stat. 5.

12. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, February 2, 1924, 1961–63; March 22, 1924, 2894; Congressional Record, 68th Cong., 1st sess., March 24, 1924, 4790–91.

13. Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, S. Rep. 68-794, 68th Cong., 1st sess., Parts 1 and 2, June 6, 1924.

14. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, S. Rep. 68-794, Part 2, June 6, 1924 and Part 3, January 15, 1925; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 1–73.

15. McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135, 174 (1927); Jake Kobrick, “United States v. Albert B. Fall: The Teapot Dome Scandal,” Federal Judicial Center, accessed June 26, 2024, https://www.fjc.gov/history/cases/famous-federal-trials/us-v-albert-b-fall-teapot-dome-scandal.

16. “Teapot Dome Likeness Seen in Radio Lobby,” Washington Post, January 12, 1937, 24; “War Assets Scandal Seen,” Baltimore Sun, June 19, 1946, 4; “Power Pact Likened to Teapot Dome,” Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1955, 1; “Pledge Given by Truman to Develop West,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1950, 1; “Watergate Joins Teapot Dome in US Scandal Vocabulary,” Christian Science Monitor, May 9, 1973, 7; Lee Roderick and Stephen Stathis, “Today Watergate—Yesterday Teapot Dome,” Christian Science Monitor, July 17, 1973, 9.

|

| 202306 12Chairman J. William Fulbright and the 1964 Tonkin Gulf Resolution

June 12, 2023

In early August 1964, two reported attacks on American navy ships in the waters of the Tonkin Gulf prompted President Lyndon B. Johnson to ask Congress to approve a joint resolution authorizing the use of force in Southeast Asia without a congressional declaration of war. Senator J. William “Bill” Fulbright of Arkansas ensured swift passage of what came to be known as the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, a role that he would later come to regret.

In early August 1964, two reportedly unprovoked attacks on American navy ships in the waters of the Tonkin Gulf near North Vietnam became key events in the evolution of congressional war powers. For nearly a decade, American policymakers had viewed South Vietnam as a critical Cold War ally. Republican and Democratic administrations had provided the independent South Vietnamese government with financial assistance and military advisors to combat ongoing threats from its communist neighbor, North Vietnam. In the summer of 1964, the U.S. military presence in South Vietnam included approximately 12,000 military advisors, as well as a naval presence in the waters of the Tonkin Gulf. On August 2, an American destroyer, the USS Maddox, came under fire by North Vietnamese boats while supporting a South Vietnamese covert operation in the Gulf. Two days later, the commander of the Maddox reported “being under continuous torpedo attack” while on patrol with a second destroyer, the USS C. Turner Joy.1

After the second reported attack, President Lyndon B. Johnson summoned congressional leaders, including Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman J. William “Bill” Fulbright of Arkansas, to the White House for a briefing. Citing the second unprovoked attack, President Johnson informed lawmakers that he would be launching retaliatory strikes against North Vietnamese targets, a unilateral action that he believed he could take in his constitutional capacity as commander in chief of the armed forces. Like President Dwight D. Eisenhower before him, Johnson wished to secure congressional approval—in advance—for any future military actions he may wish to take to protect national interests in the region. Consequently, Johnson asked lawmakers to approve the Southeast Asia Resolution to “promote the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia,” by authorizing the commander in chief “to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the … United States and to prevent further aggression.” Fulbright and his colleagues voiced their support for the air strikes and the resolution. Hours later, Johnson publicly announced that he had ordered attacks on North Vietnam while affirming that his administration did not seek a wider war.2

The next morning, Johnson personally asked Fulbright to shepherd the administration’s joint Southeast Asia Resolution, which came to be known as the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, swiftly through the Senate. The administration had modeled it after two 1950s resolutions that had provided President Dwight D. Eisenhower with congressional authorization to use military force if necessary to defend allies from Communist aggressors in Formosa (today Taiwan) and the Middle East. “The Constitution assumes that our two branches of government should get along together,” Eisenhower later recalled of the effort to obtain congressional authorization for the use of military force. He preferred that any military response be an expression of the will of the legislative and executive branches. Under Article 1, Section 8, of the Constitution, however, only Congress has the authority to declare war. During debates about the Eisenhower resolutions, Fulbright had expressed misgivings that Congress was relinquishing its constitutional war powers to the executive branch. Nevertheless, Fulbright did support the Formosa Resolution in 1955. (He was not present to cast a vote for the Middle East Resolution in 1957.) While President Eisenhower did not take the nation to war under those congressional authorizations, Congress had set a precedent in granting an administration such broad authority.3

Despite his earlier reservations, in 1964 Senator Fulbright readily agreed to shepherd the Tonkin Gulf Resolution through the Senate. Fulbright viewed President Johnson as a long-time friend and political ally. In 1959, while serving as Senate majority leader, Johnson had helped maneuver Fulbright into the coveted position of chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, and Leader Johnson fondly referred to Fulbright as “my secretary of state.” In 1960 Fulbright had supported Johnson’s candidacy in the Democratic presidential primary. Johnson won the vice-presidential nomination instead and in 1961 assumed the critical role of congressional liaison for President John F. Kennedy’s administration. In that capacity, Johnson’s warm relationship with Fulbright continued.4

As the Senate’s undisputed foreign policy expert, Fulbright understood that President Johnson had inherited a complex situation in Vietnam after Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. The domestic politics of responding to the North Vietnamese attacks on U.S. ships weighed on Fulbright’s mind as well. The resolution came “in the beginning of the contest between Johnson and [Barry] Goldwater” in the 1964 presidential election, Fulbright later recalled. “I was just overpersuaded … in my feelings that I ought to support the president.” Fulbright accepted the responsibility of delivering for the president a strong bipartisan political victory just months before the election.5

Shortly after Johnson announced the retaliatory strikes and his intention to seek congressional authorization for future military action, Americans rallied around the commander in chief. “Southeast Asia is our first line of defense; when an enemy attacks us there, he is in principle, attacking us on our native land,” declared Senator Frank Lausche of Ohio. Polls showed that the Johnson administration had the overwhelming support of the American public—with 85 percent supporting its response. A desire for peace must “not be misconstrued as weakness,” wrote the Philadelphia Inquirer. The Los Angeles Times blamed “Communists” for “escalat[ing] the hostilities—an escalation we must meet.” Johnson’s political rival endorsed his actions, too. “We cannot allow the American flag to be shot at anywhere on earth if we are to retain our respect and prestige,” Barry Goldwater announced. Retaliatory strikes, Goldwater maintained, are the “only thing [the president] can do under the circumstances.”6

President Johnson sent the Tonkin Gulf Resolution to the Senate on the morning of August 5. Fulbright met with Senate leadership and administration officials to plot a strategy for its swift passage, emphasizing the need for quick action and repeating the official administration position that “hostilities on a larger scale are not envisaged.” Staff who recalled “soul-searching” Senate debates over Eisenhower’s Middle East Resolution in 1957—a debate that lasted for 13 days—were incredulous at Fulbright’s determination to rush the resolution through the Senate, but the Arkansas senator proved persuasive. As one historian later assessed, “The administration had skillfully cultivated a crisis atmosphere that seemed to leave little room for debate.”7

On August 6, the Foreign Relations Committee chairman convened a joint executive session with the Armed Services Committee. During that session, which lasted a little more than an hour-and-a-half, senators posed few substantive questions of the witnesses representing the administration, including Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk. “As much as I would like to be consulted with on this kind of thing,” Senator Russell Long of Louisiana told the president’s advisors, “the less time you spend on consulting and the quicker you shoot back the better off you are.” Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon was the exception, challenging the administration’s claim that the attacks had been unprovoked. Tipped off by a Pentagon officer, Morse inquired if North Vietnam might have interpreted recent joint United States-South Vietnam covert operations as provocations. Secretary of Defense McNamara said no. The committee voted 14-1—Morse provided the dissenting vote—to send the resolution to the full Senate for its consideration.8

A few hours after the committee vote, Fulbright stood at his desk in the Senate Chamber and urged “the prompt and overwhelming endorsement of the resolution now before the Senate.” He had secured a unanimous consent agreement to limit the debate over the resolution to three hours, beginning that afternoon and continuing into the following morning. A final vote was scheduled for 1:00 p.m. on August 7. Despite the grave implications of the resolution, the debate was sparsely attended. A few senators expressed skepticism about the wisdom of granting the president such broad authority. Did the resolution authorize the president to “use such force as could lead into war” without a congressional declaration, John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky wondered? Yes, Fulbright conceded, the resolution did give the president such authority. “We all hope and believe that the President will not use this discretion arbitrarily or irresponsibly,” Fulbright explained. “We know that he is accustomed to consulting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff and with congressional leaders. But he does not have to do that.” The chairman reassured his colleagues, however, that the Johnson administration had denied any intent to widen the war, stating: “The policy of our Government not to expand the war still holds.”9

Chief opponent Wayne Morse was present for nearly all of the debate. He pleaded with his colleagues not to approve the resolution. “I shall not support … a predated declaration of war,” he insisted. But Fulbright’s foreign policy expertise and his close relationship with the president helped to assuage doubts about the wisdom of granting any president such sweeping authority. “When it came to foreign policy,” noted Senator Maurine Neuberger, Morse’s junior colleague from Oregon, “I did whatever Bill Fulbright said I should do.” At the conclusion of the debate, the Senate approved the resolution 88-2. Ernest Gruening of Alaska joined Morse in dissent. The House had already unanimously approved the joint resolution, and the president signed it into law on August 10, 1964.10

Fulbright had helped to deliver a major political and policy victory for his friend, President Johnson. In November, Johnson defeated Goldwater in an electoral landslide. In early 1965, under the provisions of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, Johnson vastly expanded the war in Vietnam. He approved a bombing campaign in North Vietnam and ordered the first U.S. combat troops to South Vietnam. This betrayal of his stated intent stung some of the president’s friends in Congress, especially Fulbright. More than 150,000 U.S. combat troops entered South Vietnam by the end of 1965, and that number swelled to more than 530,000 by 1968.

Wayne Morse had predicted that his Senate colleagues would come to regret their support for the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. It wasn’t long before Fulbright did. Beginning in 1966, Fulbright’s Foreign Relations Committee held a series of high-profile educational hearings about the war. Broadcast live on national television, these hearings revealed the White House’s intentional deceptions about the war’s progress and widened what came to be known as the administration’s “credibility gap.”11

The hearings deepened Fulbright’s resolve to educate the public (and his colleagues) about the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. An ongoing committee investigation revealed that the administration’s justification for retaliatory action in 1964 and even the sequence of events that precipitated the request for the Tonkin Gulf Resolution were based on obfuscations and lies. The administration had drafted the resolution months before the reported attacks of August 1964, the hearings revealed, having it ready to present to Congress when the timing was right. Despite the fact the administration had insisted that the second unprovoked attack required forceful retaliation, there was doubt at the time that the attack had occurred. On the afternoon of August 4, for example, the commander of the USS Maddox—just hours after his initial report of the attack—cabled his superiors, “Review of action makes many reported contacts and torpedoes fired appear doubtful … Suggest complete evaluation before any further action.” The administration failed to share these doubts with members of Congress.12

In 1968, as the number of American casualties in Vietnam grew, Senator Fulbright expressed regret for his role in passing the resolution. “I feel a very deep moral responsibility to the Senate and the country for having misled them,” he lamented. Fulbright devoted the remainder of his Senate career to reclaiming Congress’s constitutional war-making powers and ending the war in Vietnam.13

In 1971 Congress rescinded the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, though it continued to fund the war until the U.S. military withdrew from Vietnam in March 1973. Later that year, Congress approved the War Powers Act over President Richard M. Nixon’s veto. The law represented Congress’s desire to define the circumstances under which presidents may unilaterally commit U.S. armed forces. Congress had granted the executive branch discretionary war-making power with the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, and some had learned a powerful lesson in that experience. “If we could rely on the good faith of the Executive,” Fulbright explained during a Senate debate of the war powers bill in July 1973, “we would not need the bill. However, since we cannot do so, so we do need a bill.” The War Powers Act requires the executive branch to consult with and report to Congress any commitment of armed forces.14

Despite his achievements, Fulbright lost his bid for reelection in a 1974 primary. The War Powers Act continues to serve mainly as a framework to promote legislative and executive branch cooperation on war powers issues. Its efficacy, however, depends upon Congress’s willingness to enforce the law. Since the 1950s, Congress has authorized presidential administrations to use military force by congressional resolutions rather than by declarations of war.

Notes

1. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and Senate Committee on Armed Forces, Southeast Asia Resolution, Joint Hearing Before the Committee on Foreign Relations and the Committee on Armed Services, 88th Cong., 2nd sess., August 6, 1964, 8.

2. Randall Bennett Woods, Fulbright: A Biography (London: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 349–50; Joint Resolution to promote the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia, Public Law 88-408, 88th Cong., 2nd sess., August 7, 1965, 59 Stat. 1031; President Lyndon B. Johnson, “August 4, 1964: Report on the Gulf of Tonkin Incident,” Presidential Speeches, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidency, Miller Center at the University of Virginia, transcript and recording accessed June 2, 2023, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/august-4-1964-report-gulf-tonkin-incident; Louis Fisher, Constitutional Conflicts Between Congress and the President, 4th ed. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997), 278–79.

3. Woods, Fulbright, 221; Congressional Record, 84th Cong., 1st sess., January 28, 1955, 994; Congressional Record, 85th Cong., 1st sess., March 5, 1957, 3129; Fisher, Constitutional Conflicts, 278, 281.

4. Woods, Fulbright, 215, 353.

5. Woods, Fulbright, 348; Frederik Logevall, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 205.

6. Congressional Record, 88th Cong., 2nd sess., August 5, 1964, 18084; “A Nation United,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 6, 1964, reprinted in the Congressional Record, 88th Cong., 2nd sess., August 6, 1964, 18400; Woods, Fulbright, 354; “Times Editorials: U.S. Answer to Aggression,” Los Angeles Times, August 6, 1964, A4; Charles Mohr, “Goldwater Backs Vietnam Action by Johnson,” New York Times, August 5, 1964, 4.

7. "Pat M. Holt, Chief of Staff, Foreign Relations Committee," Oral History Interviews, September 9, to December 12, 1980, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C., 178; Logevall, Choosing War, 205; Woods, Fulbright, 347, 353.

8. Committees on Foreign Relations and Armed Services, Southeast Asia Resolution, 14, 18.

9. Ezra Y. Siff, Why the Senate Slept: The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the Beginning of America’s Vietnam War (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1999), 27; Congressional Record, 88th Cong., 2nd sess., August 6, 1964, 18399, 18402, 18409-10.

10. Congressional Record, 88th Cong., 2nd sess., August 5, 1964, 18139; Mason Drukman, Wayne Morse: A Political Biography (Portland: The Oregon Historical Society Press, 1997), 413.

11. Drukman, Wayne Morse, 413; Joseph A. Fry, Debating Vietnam: Fulbright, Stennis and Their Senate Hearings (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2006).

12. Woods, Fulbright, 350–51; Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Executive Sessions of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (Historical Series), Vol. XX, 90th Cong., 2nd sess., 1968 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2010), 281–86.

13. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Executive Sessions of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (Historical Series), Vol. XX, 90th Cong., 2nd sess., 1968 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2010), 305-306.

14. Fisher, Constitutional Conflicts, 281–87; Logevall, Choosing War, 202–5, 213; Woods, Fulbright: 340–59, 415–67; Congressional Record, 93rd Cong., 1st sess., July 20, 1973, 25088.

|

| 202304 04Treasures from the Senate Archives: Legislative-Executive Relations

April 04, 2023

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the selection of historic records featured in this month’s “Senate Stories,” which highlight the complex relationship between the Senate and the president.

Each year, during the first week of April, the Senate commemorates “Congress Week.” Tied to the date when the Senate established a quorum for the first time—April 6, 1789—Congress Week is an annual reminder of the importance of saving and preserving the records of Congress, including the selection of historic records featured in this month’s “Senate Stories,” which highlight the complex relationship between the Senate and the president.

Among the foundational principles of the U.S. Constitution is the separation of powers. In establishing three distinct branches of government—legislative, executive, and judicial—the Constitution divides authority to create the law, implement and enforce the law, and interpret the law. At the same time, many powers exercised by one branch may be shared with another. This system of checks and balances invites both compromise and conflict among the branches, especially between the legislative and executive, and prevents the consolidation of power in any single branch. For example, the Senate’s “advice and consent” is required for executive functions such as nominations and treaties. Conversely, the president has the power to veto legislation; however, Congress may overturn the veto with a two-thirds majority of those present and voting in both houses.1

The constitutional structure that provides for checks and balances is expansive and complex by design, generating an interdependence between the Senate and the executive branch that, combined with transient political interests, has historically demonstrated moments of high conflict as well as examples of great cooperation. This collection of historic documents from the Senate’s archives highlights the collaborations and the struggles that have defined the relationship between the Senate and the president. Each document, while capturing a specific moment in time with unique political conditions at play, also provides a broader view of the constitutional system of government in action, specifically the foundational principle of separation of powers and the complex system of checks and balances.

George Washington's First Inaugural Address, 1789

When George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the United States on April 30, 1789, he delivered this address to a joint session of Congress, assembled in the Senate Chamber in New York City’s Federal Hall. While this first occasion was not the public event we have come to expect, Washington's speech nevertheless established the enduring tradition of presidential inaugural addresses. Early presidential messages, including inaugural addresses and annual messages (now known as State of the Union addresses), are included in Senate records at the National Archives.

Although noting his constitutional directive as president "to recommend to your consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient," Washington refrained from detailing his policy preferences regarding legislation. Rather, on the occasion of his inaugural, he stated his confidence in the abilities of the legislators, insisting, "It will be…far more congenial with the feelings which actuate me, to substitute, in place of a recommendation of particular measures, the tribute that is due to the talents, the rectitude, and the patriotism which adorn the characters selected to devise and adopt them."

Message from President Thomas Jefferson to Congress Regarding the Louisiana Purchase, 1804

Treaty powers are among those shared by the president and the Senate. The Constitution provides that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur" (Article II, section 2). In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson's administration negotiated a treaty with France by which the United States purchased the vast Louisiana Territory. Questions arose concerning the constitutionality of the purchase, but Jefferson and his supporters successfully justified the legality of the acquisition. On October 20, 1803, the Senate approved the treaty for ratification by a vote of 24 to 7. The territory, which encompassed more than 800,000 square miles of land, now makes up 15 states stretching from Louisiana to Montana. In this congratulatory message to Congress dated January 16, 1804, President Jefferson reported on the formal transfer of the land to the United States and referenced the December 20, 1803, proclamation announcing to the residents of the territory the transfer of national authority.

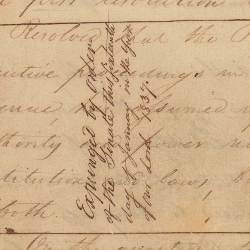

Page from the Senate Journal Showing the Expungement of a Resolution to Censure President Andrew Jackson, 1834

The March 28, 1834, censure of President Andrew Jackson represents a notably contentious episode in the executive-legislative relationship. For two years, Democratic president Andrew Jackson had clashed with Senator Henry Clay and his allies over the congressionally chartered Bank of the United States. The dispute came to a head when President Jackson, who had opposed the creation of the Bank, ordered the removal of federal deposits from the Bank to be distributed to several state banks. When his first Treasury secretary refused to do so, Jackson fired him during a Senate recess and appointed a new Treasury secretary, who carried out his orders. Senator Clay and his allies, who supported the Bank, believed that President Jackson did not have the constitutional authority to take such action, and they found the explanation given for moving the federal deposits “unsatisfactory and insufficient.” Clay introduced the resolution to censure the president, charging that Jackson had “assumed the exercise of a power over the Treasury of the United States not granted him by the Constitution and laws.” After extensive debate, the censure resolution passed. Jackson responded by submitting to the Senate a 100-page message arguing that the Senate did not have the authority to censure the president. The Senate again rebuffed the president by refusing to print the lengthy message in its Journal.2

Over the next three years, Missouri Democrat and Jackson ally Thomas Hart Benton campaigned to expunge the censure resolution from the Senate Journal. In January 1837, after Democrats regained the majority in the Senate, Senator Benton succeeded. On January 16, the secretary of the Senate carried the 1834 Journal into the Senate Chamber, drew careful lines around the text of the censure resolution, and wrote, “Expunged by order of the Senate."

President Abraham Lincoln's Nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to be Lieutenant General of the U.S. Army, 1864

Like treaty powers, the Constitution requires that the Senate serve as a check on the president's nomination authority. The president nominates federal judges, members of the cabinet, and military officials, among others, whose nominations are confirmed with the advice and consent of the Senate. This remarkable document dated February 29, 1864, representing a critical moment in the Civil War, is President Abraham Lincoln's nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to be lieutenant general of the U.S. Army, at the time the United States’ highest military rank. Previously, only two men had achieved that rank—George Washington and Winfield Scott—and Scott’s had been a brevet promotion. To facilitate Grant’s nomination and ensure his superior status among military officers, Congress passed a bill to revive the grade of lieutenant general and authorize the president "to appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, a lieutenant-general, to be selected among those officers in the military service of the United States . . . most distinguished for courage, skill, and ability." The Senate confirmed Lincoln's nomination of Grant on March 2, 1864.

Letter from President Woodrow Wilson to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, 1919

A unique event in legislative-executive relations occurred on August 19, 1919, when President Woodrow Wilson offered testimony before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations on the Treaty of Versailles, then under consideration by the committee. The meeting, convened in the East Room of the White House, stood “in contradiction of the precedents of more than a century,” the Atlanta Constitution reported, noting the rarity of a president offering testimony before a congressional committee.3

The Treaty of Versailles ended military actions against Germany in World War I and created the League of Nations, an international organization designed to prevent another world war. President Wilson had led the U.S. delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and had been a principal architect of the treaty. For months, Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Henry Cabot Lodge had encouraged the president to seek the advice of the Senate while negotiating the treaty’s terms, but Wilson chose to negotiate on his own. Personally invested in the treaty’s adoption, the president hand-delivered it to the Senate on July 10, 1919, and urged its approval for ratification in an unusual speech before the full Senate.

Under Senate rules, the treaty went to the Foreign Relations Committee for consideration, which held public hearings from July 31 to September 12, 1919. Among the most vocal critics of the proposed treaty was Lodge, who was also the Senate majority leader. Lodge opposed several elements of the treaty, particularly those related to U.S. participation in the League of Nations. On behalf of the Foreign Relations Committee, Lodge asked Wilson to meet with the committee to answer senators’ questions. With this letter, President Wilson agreed to Lodge's request and proposed the August 19 date at the White House.

Ultimately, Lodge’s committee insisted on a number of “reservations” to the treaty, but Wilson and Senate proponents of the treaty were unwilling to compromise on terms. Consequently, on November 19, 1919, for the first time in its history, the Senate rejected a peace treaty.

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, 1973

Under the Constitution, the president is permitted to veto legislative acts, but Congress has the authority to override presidential vetoes by two-thirds majorities of both houses. This document provides a comprehensive example of these constitutional checks and balances in action. In 1973 Congress passed S.518, which sought to abolish the offices of the director and deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget and reestablish those positions with a new requirement that they be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. The bill’s proponents argued that because these positions had evolved to wield significant power, they ought to be subject to Senate confirmation.

President Richard Nixon vetoed the bill on May 18, claiming it to be unconstitutional. “This step would be a grave violation of the fundamental doctrine of separation of powers,” Nixon stated. While the Senate achieved the necessary two-thirds majority to override the veto, the House did not, and Nixon’s veto was sustained. Congressional efforts to override Nixon’s veto were recorded by the secretary of the Senate and clerk of the House of Representatives on the reverse side of the bill.

The system of checks and balances set forth by the Constitution is a complex one, creating a legislative-executive relationship that is sometimes adversarial and at other times cooperative, but always interdependent. Illustrating the Senate's broad-ranging responsibilities and the integral role the Senate has played in this constitutional system, these treasured documents from the Senate’s archives help us to gain a better understanding of the conflicts and compromises that have historically defined the relationship between the Senate and the president.

Notes

1. Matthew E. Glassman, "Separation of Powers: An Overview," Congressional Research Service, R44334, updated January 8, 2016, 2.

2. Senate Journal, 25th Cong., 2nd sess., March 28, 1834, 197.

3. “Wilson Meets Senators in Wordy Duel,” Atlanta Constitution, August 20, 1919, 1.

|

| 202207 05Origins of Senatorial Courtesy

July 05, 2022

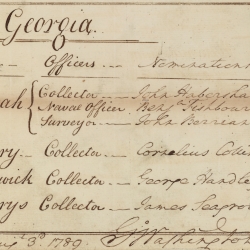

On August 5, 1789, the Senate rejected for the first time a presidential nominee. At the urging of Georgia senator James Gunn, the Senate failed to confirm Benjamin Fishbourn, President George Washington’s nominee to serve as federal naval officer for the Port of Savannah. The Senate’s rejection of Fishbourn has been regarded as the first assertion of “senatorial courtesy.”

On August 5, 1789, the Senate rejected for the first time a presidential nominee. At the urging of Georgia senator James Gunn, the Senate failed to confirm Benjamin Fishbourn, President George Washington’s nominee to serve as federal naval officer for the Port of Savannah. The Senate’s rejection of Fishbourn has been regarded as the first assertion of “senatorial courtesy,” the practice whereby senators defer to the wishes of a colleague who objects to an individual nominated to serve in his or her state. Senatorial courtesy also has been interpreted to mean that a president should consult with senators of his or her party when nominating individuals to serve in positions in their home states. Such a practice was not envisioned by the framers. In fact, in The Federalist, No. 66, Alexander Hamilton wrote: “There will, of course, be no exertion of choice [in executive appointments] on the part of Senators. They can only ratify or reject the choice of the President.”1

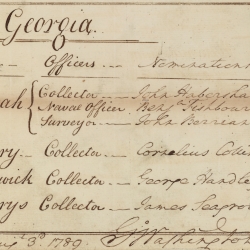

Like other office seekers, Fishbourn had written to Washington in hopes of securing a federal appointment in the new government. Fishbourn had served in the Georgia legislature and had been appointed earlier that year as state naval officer of Savannah by the state’s governor. He hoped to fill the same role for the federal government. Washington had informed Fishbourn that he would assume the presidency “free from engagements of every kind and nature whatsoever,” and would make appointments only with “justice” and “the public good” in mind. Fishbourn benefitted, however, from the support of General Anthony Wayne, under whom he had served as aide-de-camp during the Revolutionary War. Wayne had a close bond with Washington and had recommended Fishbourn for a position in the government. As a result, Fishbourn’s name was added to President Washington’s long list of nominees to serve as customs collectors, naval officers, and land surveyors throughout the country that was presented to the Senate on August 3, 1789. The Senate confirmed most of the nominees on the list the next day. Two other nominees from Georgia were confirmed on August 5, but the Senate, at the urging of Senator Gunn, rejected Fishbourn.2

Why did Senator Gunn object to Fishbourn? The drama surrounding the nomination can be traced back to a duel challenge and personal rivalries. Affairs of honor, in which men in the public eye were willing to exchange gunfire and risk death in defense of their reputations, were an important element of politics in the early American republic. In 1785 James Gunn, while serving as an army captain, feuded with Major General Nathanael Greene over a rather arcane military policy. At some point during the Revolutionary War, James Gunn’s horse was killed in battle. He was able to select a government-procured horse to use during the remainder of the war, as was custom. The problem arose when Gunn traded the horse, which was considered to be quite valuable, for two other horses and an enslaved individual. General Greene objected to the transaction, not for the atrocity that an enslaved person was considered property equivalent to a horse, but because Gunn had dispensed with government property as if it was his personal property. Greene called for a military court of inquiry to investigate. The court ruled that Gunn was justified in trading the horse, but Greene was not satisfied. He ordered Gunn to return the horse and referred the matter to the Continental Congress. Congress adopted resolutions supporting Greene’s actions and ordered Gunn to replace the horse with “another equally good.”3

After the war, both Gunn and Greene settled in Georgia. Gunn, still smarting from what he saw as Greene’s attack on his character, challenged Greene to a duel. Greene refused the challenge, claiming that a commanding officer could not be accountable to a subordinate for his actions while in command. Gunn reportedly declared that “he would attack [Greene] wherever he met him” and began to carry pistols in the event of an encounter. The confrontation never occurred, and Greene received support from Washington himself, who assured him that his “honor and reputation will stand” for refusing to accept Gunn’s challenge.4

What does all of this have to do with Fishbourn and senatorial courtesy? Fishbourn had publicly sided with Greene during the dispute, and Gunn never forgot that. When asked by another senator to explain his reasons for objecting to Fishbourn, Gunn responded simply with “personal invective and abuse.” This was enough to sway other senators to vote down the nomination.5

Angry about the rejection of his nominee, Washington wrote in a message to the Senate, “Permit me to submit to your consideration whether on occasions where the propriety of Nominations appear questionable to you, it would not be expedient to communicate that circumstance to me, and thereby avail yourselves of the information which led me to make them, and which I would with pleasure lay before you.” Washington, according to one source, even went to the Chamber to ask the Senate’s reasons for the rejection, to which Gunn informed him that the Senate owed him no explanation.6

Fishbourn was stung by the rejection. His supporters attempted to undo the damage to his reputation. Anthony Wayne wrote to Washington to assure him that the “unmerited and wanton attack upon [Fishbourn's] Character by Mr. Gunn” was groundless and that he would never have recommended Fishbourn for the position if the charges were true. Wayne published a defense of Fishbourn signed by notable men from Savannah.7

A month later, Fishbourn sent a letter to Washington in hopes of repairing his reputation after such a public embarrassment. He asked the president to write him indicating that he held no prejudices against him based on “representations having been made against me in the Senate.” As he left Georgia and public life, he hoped “I may have it to say I have the sanction as well as the good wishes of his Excellency the President of the United States.” Fishbourn was probably disappointed to receive a reply only from an aide to Washington, stating “I am directed by him to inform you that when he nominated you for Naval Officer of the Port of Savannah he was ignorant of any charge existing against you—and, not having, since that time, had any other exibit (sic) of the facts which were alledged (sic) in the Senate . . . he does not consider himself competent to give any opinion on the subject.”8

Senator James Gunn’s objection to Fishbourn for what he saw as an affront to his public honor—even if Fishbourn was but a minor player in the affair—established an enduring precedent in the Senate. Despite periodic efforts by presidents to push back on senators’ attempts to control executive appointments, the custom of senatorial courtesy became firmly established by the late 19th century. In 1906, two years prior to his run for president, William Howard Taft observed that presidents were “naturally quite dependent on . . . advice and recommendation” of senators, such that “the appointing power is in effect in their hands subject only to a veto by the President.” When considering a nomination in executive session—held behind closed doors until 1929—senators merely had to rise and announce that a nominee was “personally obnoxious” or “personally objectionable” to them, without any further explanation. They could depend on the deference of Senate colleagues in rejecting the nominee. The Senate Judiciary Committee formalized a version of senatorial courtesy through use of the “blue slip,” a blue sheet of paper on which a senator could register support for or opposition to a judicial nominee to serve in his or her state. In 1960 William Proxmire of Wisconsin called senatorial courtesy “the ultimate senatorial weapon,” a “nuclear warhead intercontinental ballistic missile of Senate nomination action.” While there have been changes to the rules and customs governing Senate advice and consent over the past half century—for example, senators no longer announce on the floor that a nominee is “personally obnoxious” to them—individual senators continue to exert a great deal of power over the nomination and confirmation process.9

Notes

1. Robert C. Byrd, The Senate, 1789-1989: Addresses on the History of the United States Senate, vol. 2, ed. Wendy Wolff, S. Doc. 100-20, 100th Cong., 1st sess. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1991), 31; Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 66, quoted in George H. Haynes, The Senate of the United States: Its History and Practice (Cambridge: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1938), 2:736.

2. Mitchel A. Sollenberger, “Georgia’s Influence on the U. S. Senate: A Reassessment of the Rejection of Benjamin Fishbourn and the Origin of Senatorial Courtesy,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 93, no. 2 (2009): 182–90; “From George Washington to Benjamin Fishbourn, 23 December 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0148. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 24 September 1788 – 31 March 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987), 198–200.]; “To George Washington from Anthony Wayne, 10 May 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-02-02-0189. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 2, 1 April 1789 – 15 June 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987), 261–64.]

3. Joanne B. Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the Early Republic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); George R. Lamplugh, “The Importance of Being Truculent: James Gunn, the Chatham Militia, and Georgia Politics, 1782–1789,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 80, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 228–29; Sollenberger, “Georgia’s Influence,” 185–87.

4. Sollenberger, “Georgia’s Influence,” 187; Lamplugh, “Importance of Being Truculent,” 232.

5. Fergus M. Bordewich, The First Federal Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2016), 132; Lamplugh, “Importance of Being Truculent,” 240–43.

6. “From George Washington to Benjamin Fishbourn, 23 December 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0148. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 198–200.] Washington’s visit to the Senate was recounted years later by the son of Washington aide Tobias Lear. Notably, William Maclay was absent on that day, but he committed to his diary the comments of a fellow senator about Washington’s intemperate response to the rejection, though it is not clear if that occurred in person in the Senate chamber. Kenneth R. Bowling and Helen E. Veit, eds., Diary of William Maclay and Other Notes on Senate Debates, vol. 9 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 121.

7. “To George Washington from Anthony Wayne, 30 August 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-03-02-0330. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 3, 15 June 1789–5 September 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 569–70.]

8. “To George Washington from Benjamin Fishbourn, 25 September 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-04-02-0054 [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 4, 8 September 1789 – 15 January 1790, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), 81–83; fn1.] This was quite a change in tone from December 1788, when Washington wrote in a letter to Fishbourn: “For you may rest assured, Sir, that, while I feel a sincere pleasure in hearing of the prosperity of my army acquaintances in general, the satisfaction is of a nature still more interesting, when the success has attended an officer with whose services I was more particularly acquainted.”; “From George Washington to Benjamin Fishbourn, 23 December 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0148 [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 198–200.]

9. William Howard Taft, Four Aspects of Civic Duty (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 98–99, quoted in Haynes, Senate of the United States, 1:736; Congressional Record, 86th Cong., 2nd Sess., April 19, 1960, 8159; Michael J. Gerhardt, The Federal Appointments Process (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), 143–53.

|

| 202107 01Reasserting Checks and Balances: The National Emergencies Act of 1976

July 01, 2021