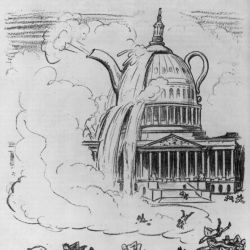

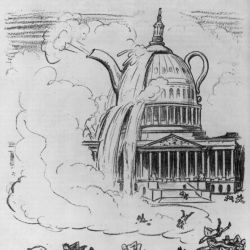

| 202407 01100 Years Since Teapot Dome

July 01, 2024

A century ago, in June 1924, the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys released a report, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, that outlined one of the worst breaches of the public trust in American history. The Senate investigation into the scandal, popularly known as Teapot Dome and led by Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, uncovered widespread corruption between government officials and powerful corporate interests. The inquiry serves as a powerful example of effective congressional oversight, highlighting the ability of lawmakers to expose wrongdoing to protect the public interest.

A century ago, in June 1924, the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys released a report, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, that outlined one of the worst breaches of the public trust in American history. The Senate investigation into the scandal, popularly known as Teapot Dome and led by Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, uncovered widespread corruption between government officials and powerful corporate interests. The inquiry serves as a powerful example of effective congressional oversight, highlighting the ability of lawmakers to expose wrongdoing to protect the public interest.

The seeds of the Teapot Dome scandal were planted in the first decade of the 20th century, when President Theodore Roosevelt and conservationists in Congress took steps to protect public lands from unlimited private exploitation. Concerned with ensuring the national government had access to energy resources and anticipating the conversion of the nation’s naval fleet from coal-burning to oil-burning power, Roosevelt instructed the U.S. Geological Survey to survey oil reservoirs beneath public lands. In 1909 President William Howard Taft responded to the Survey’s findings by signing an executive order withdrawing three million acres of public lands in California and Wyoming from private settlement and development and designating portions of these public lands in California, known as Elk Hills and Buena Vista, as naval oil reserves. In 1915 President Woodrow Wilson added a third naval oil reserve in Wyoming, named Teapot Dome after a sandstone rock formation that resembled a teapot. Congress by law in 1920 placed these reserves under the supervision of the secretary of the navy, who was given wide latitude “to conserve, develop, use, and operate the oil reserves” in the national interest.1

In the years after the reserves were created, the nation’s largest oil companies began plotting to obtain leases for drilling. The amount of oil in the reserves, and the money that could be made by extracting it, was staggering. Surveys estimated that the three reserves combined held 435 million barrels of oil, almost equal to the total amount of oil that had been produced in the country to that point. Extracted, those resources were estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, at least a billion in today’s dollars.2

In 1921 Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall was also keenly interested in the reserves. Fall was a former gold and silver prospector and attorney who had been elected to serve as one of New Mexico’s first senators in 1912. Known for his volatile personality and his frontiersman ways—he reportedly often carried a six-shooter pistol—Fall enjoyed the support of prominent industrialists who had helped finance his 1918 re-election campaign and provided backing for Fall’s purchase of a prominent Albuquerque newspaper. In the Senate, Fall became friends with fellow Republican senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio (who had joined the Senate in 1915), the two bonding over whiskey and poker games—then a popular Washington pastime. When Harding was elected president in 1920, he nominated Fall to be his secretary of the interior. Fall had plans to open the nation’s public lands to private development, and he persuaded the president to place the naval reserves under his control. On May 31, 1921, Harding signed an executive order transferring control of the naval reserves from the Navy Department to the Interior Department.3

Rumors swirled for months about Fall’s plans to develop the reserves. On April 12, 1922, Fall offered to his friend Harry F. Sinclair, the head of Sinclair Oil, an exclusive, no-bid lease for the Teapot Dome oil reserves. Intending to keep the deal a secret, Fall locked the contract in his desk and instructed the assistant secretary to tell no one about it. But intrepid reporters soon uncovered the story. On April 14, 1922, the Wall Street Journal ran a front-page exposé detailing the sweetheart deal. The Denver Post was not far behind, offering details about what it called “one of the baldest public land-grabs in history.”4

Independent oil producers saw the press coverage and, angry at not having had an opportunity to bid on the leases, complained to Wyoming Democratic senator John B. Kendrick about the secret negotiations of the Teapot Dome deal. When Kendrick inquired about the details of the lease from the Interior Department, Fall’s subordinates gave him the runaround. On April 15, Kendrick introduced a resolution in the Senate instructing the secretaries of the interior and the navy to inform the Senate about any ongoing negotiations for leases on Teapot Dome. Now under intense pressure, Fall released a statement to the press on April 18 announcing the Teapot Dome lease and disclosing the impending completion of another lease for the Elk Hills reserve to oil baron Edward Doheny and his Pan-American Oil Company. On April 20, Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, a progressive Republican and a leading conservationist in the Senate, introduced a resolution demanding from the Interior Department all documents relating to the negotiation and execution of leases on the naval oil reserves. The Senate amended the resolution to authorize the Committee on Public Lands and Surveys to conduct a full-scale investigation and approved it by unanimous vote (with 38 senators not voting) a week later.5

In early June, Fall submitted to President Harding a 75-page report and thousands of supporting documents detailing the history of the naval oil reserves and the geological data that Fall claimed justified the leases. Harding sent the report to the Senate with a memo stating that all policies regarding the reserves had been reviewed by him and “at all times had my entire approval.”6

The Teapot Dome investigation was slow to get off the ground. The first challenge was getting someone to lead it. While La Follette had been the driving force to authorize the inquiry, he was not a member of the Committee on Public Lands. The Republican chair of the committee was Reed Smoot of Utah, a conservative who was not enthusiastic about pursuing an investigation that could be politically damaging for his party. John Kendrick served on the Public Lands Committee but did not want to take on the task. La Follette and Kendrick persuaded Democrat Thomas Walsh of Montana to lead the investigation.

The son of Irish Catholic immigrants, Walsh had been an attorney in Helena, Montana, before becoming a powerful force in the state’s Democratic Party. Elected to the Senate in 1912, Walsh had a reputation as an able lawyer and a progressive willing to take on the powerful mining interests in his state. Walsh was the most junior member of the minority party on the committee, but the ranking Democrat was leaving the Senate after 1922, and La Follette and Kendrick opted to bypass the other more senior Democrats. Walsh was not a conservationist and had, to that point, been a supporter of opening up public lands—and Native American reservations—for resource exploitation. He was initially reluctant to commit to the investigation, but after some prodding from fellow Montana Democrat Burton K. Wheeler, he agreed in June 1922 to wade in and began reviewing the mountain of documents submitted by Fall.7

Walsh worked through the evidence methodically throughout the summer and fall of 1922, and by early 1923, he began to suspect that Fall had engaged in misconduct. In February 1923, with the Senate set to adjourn in March, the Public Lands Committee set a hearing date for October, a little more than a month before the 68th Congress would convene in December. By the time Walsh returned to Washington in September to begin preparing for the hearing, Albert Fall had resigned from the cabinet to go work for Sinclair, President Harding had died of a heart attack, and Vice President Calvin Coolidge had become president.8

When the hearings began on October 23, 1923, the main question facing the committee was whether Albert Fall was justified in secretly leasing the naval reserves without competitive bidding. Chairman Smoot called the committee to order and then turned over the proceedings to Walsh, who took the lead in questioning witnesses. In the opening round of questioning, Walsh challenged Fall on the legality of Harding transferring control over the naval reserves to him as secretary of the interior and argued that Congress had clearly intended for the secretary of the navy to be the steward of its oil. Fall contended that the president was in his rights to give him responsibility over the reserves. He defended his quick action in granting leases as necessary to prevent the reserves from being depleted by drainage—the intentional depletion of reserves by adjacent landowners. Reports from the Bureau of Mines had indicated that drainage was not a concern, but geologists hired by the committee at the behest of Chairman Smoot disagreed, claiming that the reserves were draining at a rapid rate and that only 25 million barrels of oil remained. Under questioning, Fall defended his selection of Sinclair as a sound business decision and the deal’s secrecy as a matter of national security. Smoot opined that “if the reports of the experts are accepted, the theory that the government made a mistake in leasing this reserve has been exploded.”9

Walsh had other sources, however, that opened up new avenues of investigation. Journalists from Denver and New Mexico—including Carl Magee, who had purchased Fall’s newspaper from him in 1920—told Walsh about a suspicious, abrupt change in Fall’s personal finances. Brought before the committee on November 30, Magee testified that Fall had been cash-poor in 1921 and a decade in arrears on the property taxes of his dilapidated New Mexico ranch. But in June 1922 Fall, suddenly flush with cash, paid his back taxes, purchased neighboring properties, and made substantial improvements to his previously rundown ranch. The burning question became, where did Fall get all of this money?10

By the time Walsh completed his questioning of witnesses in January 1924, he had uncovered suspicious payments made to Fall. Harry Sinclair gave Fall $269,000 in Liberty Bonds and cash a month after signing the Teapot Dome lease. Edward Doheny, to whom Fall awarded the Elk Hills reserve lease, testified that he instructed his son to deliver $100,000 (well over $1 million in today’s money) in cash to Fall “in a little brown satchel,” allegedly as a loan, but one that Fall had lied about and tried to conceal from Walsh and the committee. In a closed committee meeting, Walsh informed his colleagues that he would be introducing a resolution directing the president to appoint a special counsel to bring civil suits to cancel the naval reserve leases and to pursue criminal charges connected to awarding the leases. Republican Irvine Lenroot, now chair of the Public Lands Committee, informed President Coolidge of Walsh’s intentions and urged him to get out in front of the news. On January 27 Coolidge announced his intent to appoint counsel and file charges, and a few days later the Senate passed Walsh’s resolution.11

Walsh was not done with his investigation, however. What had begun in late 1923 as a quiet set of hearings in a small committee room soon became a public sensation with audiences packed into the spacious Caucus Room on the third floor of the Senate Office Building. Walsh recalled Fall to face more questioning, but Fall delayed, claiming ill health. When he finally returned on February 2, 1924, Fall refused to answer any additional questions, claiming his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself and further arguing that the imminent appointment of special prosecutors ended the committee’s authority over the case. When Sinclair came back for more questioning in March, he refused to answer questions as well, though he didn’t bother to cite his Fifth Amendment rights. “There is nothing in any of the facts or circumstances of the lease of Teapot Dome which does or can incriminate me,” he stated. The Senate referred contempt charges against both Fall and Sinclair to the District of Columbia courts.12

The Public Lands Committee concluded its hearings in May 1924, and a bipartisan majority issued its final report in June, signed by Edwin Ladd of North Dakota, who had become committee chair in March. Some senators and representatives, particularly Democrats, criticized the report for its lack of drama and its failure to draw conclusions about the corrupting influence of oil interests in government. Still, the report included additional evidence of corruption, including Sinclair’s payments to buy off rival claimants to the reserves, as well as a $1 million payment to newspaper publishers in exchange for their silence when they discovered the shady circumstances surrounding the Teapot Dome lease.13

The committee noted “rumors” of a broader conspiracy on the part of prominent oil companies to place Harding in the White House and Fall in the Interior Department for the very purpose of exploiting natural resources on public lands but concluded only that “the evidence failed to establish the existence of such a conspiracy.” Five Republicans on the committee, led by Smoot, issued a minority report complaining that the majority had not given them time to review the report and all the supporting evidence. In January 1925, a minority of the committee issued a more substantive report defending many aspects of the Harding administration’s handling of the naval reserves and criticizing Walsh for dedicating space in the report to what it saw as baseless rumors about political conspiracies. Historians who have dug into the scandal have since given these theories more credence.14

Civil and criminal litigation involving the oil reserve leases dragged on for the next six years, with several cases going before the Supreme Court. In the end, the government proved that the leases had been illegally obtained and successfully regained control of the naval reserves. Fall was found guilty of accepting a bribe from Sinclair and sentenced to a year in prison, the first cabinet official in U.S. history to be convicted of a felony. Juries acquitted Sinclair and Doheny on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government, however. Sinclair served prison time for contempt of court—he was found guilty of attempting to intimidate the jury in his criminal trial—and contempt of Congress. The Supreme Court heard his appeal, upheld his conviction, and recognized the Senate’s investigatory power and its authority to compel testimony from witnesses. In another contempt case arising out of a related investigation into Harding administration corruption, the Court held in the McGrain V. Daugherty decision, “We are of opinion that the power of inquiry—with process to enforce it, is an essential and appropriate auxiliary of the legislative function.”15

The Teapot Dome scandal cast a long shadow over American politics, for decades serving as a symbol of the highest form of government corruption. Lawmakers investigating charges of corruption in the decades that followed the scandal would inevitably make the comparison, warning the public that they may find evidence of “another Teapot Dome” or something “worse than Teapot Dome.” In 1950, commenting on the development of the western United States, President Harry Truman stated, “The name Teapot Dome stands as an everlasting symbol of the greed and privilege that underlay one philosophy about the West.” In 1973, as Watergate coverage flooded the national media, some reporters called it “the new Teapot Dome.” “For half a century, [Teapot Dome] has, for many Americans, represented the quintessence of corruption in government,” wrote one correspondent. “Now Teapot Dome has been shoved aside by contemporary events.”16

For the Senate, the Teapot Dome investigation firmly established the authority of Congress to question the executive branch and demand information about its operations. Senator Walsh’s diligent and tenacious search for the truth uncovered corruption and held the government accountable to the people it serves, setting a standard for future Senate investigations to emulate.

Notes

1. Hasia Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” in Congress Investigates: A Critical and Documentary History, vol. 1, eds. Roger Bruns, David Hostetter, and Raymond Smock (Byrd Center for Legislative Studies, 2011), 460; Laston McCartney, The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Bought the Harding Whitehouse and Tried to Steal the Country (New York: Random House, 2019), 28–29, 96.

2. Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves: Hearings Pursuant to S. Res. 282, S. Res. 294, and S. Res. 434, 68th Cong., October 31, 1923, 678. Experts of the time disagreed as to how much oil was held in the reserves. The Bureau of Mines estimated that Teapot Dome held 135 million barrels of oil, for example, but geologists employed by the Committee on Public Lands estimated it at only 12 to 26 million. These estimates turned out to be very low. The Elk Hills reserve alone has yielded more than a billion barrels of oil in the century since. “Elk Hills Is Source of Controversy,” New York Times, April 1, 1975, 10.

3. David Hodges Stratton, Tempest Over Teapot Dome: The Story of Albert B. Fall (Tulsa: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 148–49; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 31–35, 65–67.

4. Quoted in McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 127.

5. S. Res. 277, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 15, 1922; S. Res. 282, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 29, 1922; Congressional Record, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 29, 1922, 6092–97.

6. Naval Reserve Oil Leases, Message from the President of the United States, S. Doc. 67-210, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., June 8, 1922.

7. J. Leonard Bates, Senator Thomas J. Walsh: Law and Public Affairs from TR to FDR (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 201–11; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 160.

8. Bates, Senator Thomas J. Walsh, 210–11.

9. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, October 23, 24, 1923, 175–282; “Experts Uphold Teapot Dome Lease,” New York Times, October 23, 1923, 23, quoted in McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 171.

10. Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” 464; Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, November 30, 1923, 830–43.

11. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, January 24, 1924, 1772; Diner, “The Teapot Dome Scandal, 1922–1924,” 466–68; Joint Resolution Directing the President to institute and prosecute suits to cancel certain leases of oil lands and incidental contracts, and for other purposes, Public Resolution 68–4, 68th Cong., 1st sess., February 3, 1924, 43 Stat. 5.

12. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, Hearings, February 2, 1924, 1961–63; March 22, 1924, 2894; Congressional Record, 68th Cong., 1st sess., March 24, 1924, 4790–91.

13. Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, S. Rep. 68-794, 68th Cong., 1st sess., Parts 1 and 2, June 6, 1924.

14. Leases Upon Naval Oil Reserves, S. Rep. 68-794, Part 2, June 6, 1924 and Part 3, January 15, 1925; McCartney, Teapot Dome Scandal, 1–73.

15. McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135, 174 (1927); Jake Kobrick, “United States v. Albert B. Fall: The Teapot Dome Scandal,” Federal Judicial Center, accessed June 26, 2024, https://www.fjc.gov/history/cases/famous-federal-trials/us-v-albert-b-fall-teapot-dome-scandal.

16. “Teapot Dome Likeness Seen in Radio Lobby,” Washington Post, January 12, 1937, 24; “War Assets Scandal Seen,” Baltimore Sun, June 19, 1946, 4; “Power Pact Likened to Teapot Dome,” Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1955, 1; “Pledge Given by Truman to Develop West,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1950, 1; “Watergate Joins Teapot Dome in US Scandal Vocabulary,” Christian Science Monitor, May 9, 1973, 7; Lee Roderick and Stephen Stathis, “Today Watergate—Yesterday Teapot Dome,” Christian Science Monitor, July 17, 1973, 9.

|

| 202210 06A World War II Combat Tour for Senators

October 06, 2022

On July 25, 1943, shortly after Allied forces invaded Sicily and Allied bombers targeted Rome, five United States senators set out on a unique and controversial journey: to inspect American military installations engaged across the globe in the Second World War. They boarded a converted bomber named the “Guess Where II” at Washington National Airport to begin a 65-day tour of U.S. military installations around the world.

On July 25, 1943, shortly after Allied forces invaded Sicily and Allied bombers targeted Rome, five United States senators set out on a unique and controversial journey: to inspect American military installations engaged across the globe in the Second World War. They boarded a converted bomber named the “Guess Where II” at Washington National Airport (now Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport) to begin a 65-day tour of U.S. military installations around the world. Each senator wore a dog tag and carried one knife, one steel helmet, extra cigarettes, emergency food rations, manuals on jungle survival, and two military uniforms. The senators were to wear the military uniforms while flying over enemy territory and visiting U.S. field operations in the hope that, if captured, they would be treated humanely as prisoners of war.1

The idea for this inspection tour originated among members of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs and the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, also known as the Truman Committee. The Military Affairs Committee had been examining every aspect of war mobilization, from soldier recruitment to weapons and supply contracts. The Truman Committee, chaired by Missouri senator Harry Truman, had spent two years exposing waste and corruption in the awarding of defense contracts, including in the construction of military facilities around the United States. Both committees wished to expand their investigations to include inspections of facilities overseas and initially quarreled over which panel would take on the task. The Truman Committee received approval for a tour from General George C. Marshall and President Franklin D. Roosevelt in early 1943. Albert “Happy” Chandler of Kentucky, who chaired a Military Affairs subcommittee also planning overseas inspections, protested and stated that he already had “an understanding” with the War Department about a tour of military bases. Chandler took his case to General Marshall and petulantly told reporters that “maybe the Army ought to take up its legislation with the Truman Committee.”2

The army did not want the “embarrassment” of choosing between the two committees, so the White House tasked Majority Leader Alben Barkley and Republican Leader Charles McNary with reaching a compromise. In July Barkley, who initially opposed the idea of any senators traveling abroad and taking up the time of military commanders, announced the creation of a small, bipartisan ad hoc committee of five senators to take the trip, chaired by Georgia Democrat Richard Russell and composed of two members from the Truman Committee and two from Military Affairs—Ralph O. Brewster of Maine, Happy Chandler of Kentucky, James Mead of New York, and Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., of Massachusetts.3

The committee's goals were to observe the condition and morale of American troops, the quality and effectiveness of war materiel under combat conditions, and the operations of distributing military and civilian supplies to the Allied front lines. The investigatory committee believed, as Russell later explained, that what they learned on the trip would be helpful “in dealing with questions arising from our relations with the other Allied powers, and in preparing for the many trying and complex issues whose solution must have final approval by the Senate after the war is over.” In particular, the committee was concerned about securing access rights at the war’s conclusion to military installations that the U.S. had helped to establish overseas.4

As laudable as this mission seemed, departing members received a good deal of criticism both from colleagues and constituents. At a time of stringent gasoline rationing, a constituent wrote Russell that it would be wiser to allocate his aircraft's fuel to the needs of “your Georgia people.” Senator Bennett Clark of Missouri suggested that military commanders would not “let them see enough to stick in their eye.” The senators were determined to prove Clark wrong.5

The senators' first stop was England, where they bunked with the Eighth Air Force, dined with the king and queen, and interviewed Prime Minister Winston Churchill. They moved on to North Africa, spending a week in various cities along the Mediterranean Sea. From there they toured installations in the Persian Gulf, where U.S. supplies were being shipped to support the Soviet Union. They continued on to India, China, Australia, and Hawaii before returning home on September 28. The flight from the British colony of Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka) to the west coast of Australia, 3,200 miles over water, was the first time anyone had flown nonstop over the vast Indian Ocean in a land-based plane. Along the way the senators met with commanders and high-ranking civilian officials as well as enlisted men and wounded soldiers. In total the trip took 65 days and logged 40,000 miles.6

Upon their return, Russell had planned to brief the Senate at a secret session set for October 7. Before that briefing, however, Military Affairs Committee member Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., upstaged Russell by giving his own account in public session, a move that angered the chairman. Russell shared the committee’s report with his colleagues as planned and the next day had summary findings inserted into the Congressional Record for public consumption. The report framed the key issues of postwar reconstruction and policy, including recommendations for continued U.S. access to overseas military bases, the prospects of continued foreign aid after the fighting stopped, and a proposal for merging American military branches into a single department after the war.7

The report set a firm precedent for future overseas travel by senators, with additional trips taking place in 1945. Senator James M. Tunnell led a subcommittee of the Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, known as the Mead Committee after the departure of Harry Truman, on another visit to military installations in North Africa and the Middle East in early 1945. In May 1945, after Germany had surrendered, Russell guided a group of eight senators from the Military Affairs and Naval Affairs committees on a trip to France and Germany, where some of the hardest fighting of the war had taken place.8

While some observers had doubted the utility of the 1943 tour, the detailed report of Russell’s committee persuaded them that the senators had completed a useful task, setting the stage for future congressional delegations (CODELs). New York Times columnist Arthur Krock, who admitted that he had his reservations about the trip, afterwards praised the group for its careful examinations and declared the trip “an excellent illustration of what can be done by Congress by the use of the effective and responsible committee system.”9

Notes

1. George C. Fite, Richard B. Russell, Jr., Senator from Georgia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 189.

2. “2 Senate Committees Wrangle Over Who Rates Africa Tour,” Washington Post, April 9, 1943, 1; Fite, Richard B. Russell, 188–89.

3. “Avoids Ruling on Junkets,” Baltimore Sun, April 18, 1943, 15; “Five Senators to Tour World in Army Plane,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 1, 1943, 5; “War Will Continue Until 1945, Warn Senators Back from Tour,” Washington Post, September 30, 1943, 1.

4. Katherine Scott, “A Safety Valve: The Truman Committee’s Oversight during World War II,” in Colton C. Campbell and David P. Auerswald, eds., Congress and Civil Military Relations (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2015), 36–52; Congressional Record, 78th Cong., 1st sess., October 28, 1943, 8860; “Senators Seek Post-War Base Showdown Now,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 04, 1943, 8.

5. “Senators to Visit Our Forces Abroad,” New York Times, July 1, 1943, 8.

6. Congressional Record, 78th Cong., 1st sess., October 28, 1943, 8860; “Senators Reach Hawaii,” New York Times, September 23, 1943, 6; Fite, Richard B. Russell, 191.

7. Fite, Richard B. Russell, 193; Congressional Record, 78th Cong., 1st sess., October 8, 1943, 8189–90.

8. Fite, Richard B. Russell, 195–96.

9. “War Tour By Senators Promises Wide Benefits,” New York Times, October 3, 1943, E3.

|

| 202107 01Reasserting Checks and Balances: The National Emergencies Act of 1976

July 01, 2021

In 1973 the Senate assigned a herculean task to a small temporary committee. The Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency (renamed the Special Committee on National Emergencies and Delegated Emergency Powers in 1974), co-chaired by Democrat Frank Church of Idaho and Republican Charles Mathias of Maryland, would investigate outdated emergency powers granted to presidents by Congress in the previous half century. The inquiry’s surprising findings convinced Congress to pass the National Emergencies Act of 1976.

In 1973 the Senate assigned a herculean task to a small temporary committee. The Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency (renamed the Special Committee on National Emergencies and Delegated Emergency Powers in 1974), co-chaired by Democrat Frank Church of Idaho and Republican Charles Mathias of Maryland, would investigate outdated emergency powers granted to presidents by Congress in the previous half century. The inquiry’s surprising findings convinced Congress to pass the National Emergencies Act of 1976.

The story of this obscure Senate committee begins with the Vietnam War. In 1968 Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon pledged to end the war if elected. In the spring of 1970, however, President Nixon secretly expanded the war into Cambodia—without congressional approval. Weeks later, Nixon announced the expansion of the war into Cambodia on national television. The administration’s actions infuriated many senators, especially Frank Church, a long-time Vietnam War critic. Church drafted a proposal—later known as the Cooper-Church amendment—to prevent congressionally appropriated funds from being used in Cambodia. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird quickly rendered this effort moot. If Congress halted funding for the Cambodia effort, Laird warned, the Pentagon would fund the operation under the emergency provisions of a Civil War-era law called the Feed and Forage Act. With that law, Congress had granted the U.S. Cavalry the authority to purchase feed for its horses if previously appropriated money had run out while Congress was not in session. Laird explained that the provision had been used in 1958 in Lebanon and in 1961 in Berlin to fund U.S. military actions.1

The administration’s ability to circumvent Congress under the authority of a century-old law troubled Church. He had developed a reputation among his colleagues as a checks and balances proselytizer, routinely sermonizing that growing executive power threatened the health of constitutional government. When Nixon’s predecessor, Democrat Lyndon Johnson, occupied the White House, Democratic majorities in Congress felt little urgency to limit the powers of a president of their own party, and Church’s homilies fell on deaf ears, but the Nixon administration’s invasion of Cambodia converted some of Church’s colleagues to his cause. One of them, Republican Charles “Mac” Mathias of Maryland, insisted that Congress had a role to play in holding every president accountable—regardless of party. On January 6, 1973, the Senate created the Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency. Church and Mathias would lead the inquiry, joined by six colleagues and a small committee staff.

Identifying the powers that Congress had conferred on presidents during times of emergency proved to be a complex task. In the pre-personal computer era, searching hundreds of printed government publications for delegated emergency powers was extraordinarily time-consuming. After months of digging, committee staff learned that the U.S. Air Force maintained a searchable list of statutes on a computer in Colorado. Using that database and other published paper sources, investigators painstakingly compiled a list of 470 powers that Congress had granted to presidents in the previous 50 years during times of crisis, such as depression or war. “Taken together, these hundreds of statutes clothe the president with virtually unlimited power with which he can affect the lives of American citizens in a host of all-encompassing ways,” Church wrote, including seizing property and commodities, instituting martial law, and controlling transportation and communication. Though these crises had ended, Congress had not officially cancelled or revoked the powers it had granted to administrations to address them. As the Nixon administration had demonstrated, presidents could exercise these powers without congressional approval. Four national emergencies remained in effect—including one on the books since 1933! “It may be news to most Americans,” explained one Washington Post reporter, that “we have been living for at least 40 years under a state of emergency rule.”2

The committee’s investigation found that the legislative branch had rarely limited presidents’ emergency powers. The judicial branch, by contrast, had occasionally constrained those powers. For example, the Supreme Court firmly rebuffed President Harry Truman during the Korean War. The president had issued an executive order to seize control of some steel mills in 1952. Truman insisted that, as commander in chief, he had the authority to take action to avoid steel production slowdowns likely to be caused by an anticipated labor strike. The Court’s landmark decision in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer found that no law provided for the president to seize control of private property. Associate Justice Robert Jackson wrote that presidents enjoyed maximum power when they worked under the express or implied authority of Congress, but presidents who took steps explicitly at odds with the wishes of Congress worked “at [the] lowest ebb” of their constitutional power.3

The committee’s exhaustive research as well as several high-profile congressional investigations, including the Senate Watergate inquiry of 1973–74, convinced many in Congress that the time had come to reassert congressional checks and balances. The House introduced the National Emergencies Act in 1975 and the Senate passed a slightly amended version of that bill by voice vote in August 1976. The House agreed to the Senate’s amended bill, and President Gerald Ford signed the National Emergencies Act into law on September 14, 1976. The new law ended four existing states of emergency and instituted accountability and reporting requirements for future emergencies.4

Notes

1. Frank Church, “Ending Emergency Government,” American Bar Association Journal 63 (February 1977): 197–99.

2. “Bill Miller, Staff Director, Church Committee," Oral History Interview, May 5, 2014, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.; Church, “Ending Emergency Government,” 197–99; Ronald Goldfarb, “The Permanent State of Emergency,” Washington Post, January 6, 1974, B1; Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency, Emergency Powers Statutes: Provisions of Federal Law Now in Effect Delegating to the Executive Extraordinary Authority in Time of National Emergency, S. Rep. 93-549, 93rd Cong., 1st sess., November 19, 1973.

3. "Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer," Oyez, accessed June 16, 2021, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/343us579.

4. “Major Congressional Action: National Emergencies,” Congressional Quarterly Almanac 32 (Washington: Congressional Quarterly, 1976): 521–22.

|