In May 1971 newspapers heralded the end of a long tradition when the Senate approved a resolution to allow the appointment of three female pages: Paulette Desell, Ellen McConnell, and Julie Price. “New Pages in Senate’s History: Girls,” announced the Washington Post. “Senate pages have always been boys, altho [sic] there is no regulation against the appointment of girls,” reported the Chicago Tribune.1

On one hand, the Tribune was correct. There had never been a rule prohibiting the appointment of female pages in the Senate. On the other hand, the story inaccurately identified Desell, McConnell, and Price as the first female Senate page appointments. While the efforts of these three teenagers who successfully petitioned for their appointments were historically significant at the time, Senate historians have recently learned that the Senate appointed female pages at least as early as 1907. Emma Madeen served as a Senate riding page from June to December of that year, one of eight female riding pages who served between 1907 and 1926. The “discovery” of female riding pages in the early 20th century prompts a question: In an institution as old as the Senate, how can historians be certain that any event is a Senate “first”?

The appointment of Senate pages is one of the Senate’s oldest traditions. It began in 1824 when 12-year-old James Tims, the relative of Senate employees, was listed in the compensation ledger as “boy—for attendance in the Senate room.” In 1837 Senate employment records showed the position of “page” to identify young messengers who provided support for Senate operations. The titles and responsibilities of pages evolved with the institution. There were “mail boys” who helped with mail delivery, “telegraph pages” who delivered outgoing messages between the Capitol’s telegraph offices, “telephone pages” who received telephone messages, and “riding pages” who carried messages from the Senate to executive departments and the White House on horseback.

Though it is difficult to pinpoint the precise date of the Senate’s first riding page appointment, Senate records indicate that they served during the Civil War. An 1862 Senate expense report includes payment for the rental of two saddle horses and two letter bags for use by “riding pages.” During the war, riding pages delivered messages throughout Washington on horseback, a fast and relatively safe way to navigate a city pockmarked by open sewers, crisscrossed by muddy roads, and infiltrated by Confederate spies. The position continued long after the war. In 1880 Senate ledgers recorded back pay for riding page Andrew F. Slade, the first known African American page to serve in the Senate, and the title of “riding page” was listed on the secretary of the Senate’s report of expenses that year.2

By the late 1880s, riding pages did not rely solely on horses to navigate the city. The Senate appointed Carl A. Loeffler in 1889 as a riding page under the patronage of Senator Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania. When he arrived at the Senate, Loeffler learned that riding pages had recently experimented with using the city’s horse car system to deliver their messages. Horse-drawn trolley cars, or “horse cars,” were a popular mode of transportation in the 1880s, with systems in many large American cities, including New York, Boston, and Washington, DC. Horse cars allowed passengers to avoid walking on crowded and sometimes muddy streets. But riding pages needed to quickly deliver messages throughout the city’s federal departments and return promptly to the Capitol, and horse cars, which made frequent stops, proved to be an impractical option. By the 1890s, riding pages had largely abandoned the use of horse cars and, with Senate permission, adopted bicycles—the latest transportation innovation. However, Senate pages continued to deliver messages and packages on horseback through the 1910s, likely until the Senate formally closed its horse stables in 1914, as recorded in the secretary of the Senate’s annual report that year. The duties of the Senate riding pages have evolved alongside the Senate’s own evolving roles and responsibilities. By the 1950s, riding pages delivered messages to executive agencies by car, for example, making the position best suited for adult Senate staff. And while the role of the riding page has continued into the 21st century, modern Senate riding pages have not been a part of the Senate’s formal page program.3

Senate riding pages enjoyed many perks. In 1899 the annual salary for a riding page was $912.50, a considerable sum when compared with the salary of a Senate document folder ($840), or a laborer ($720). In addition to good pay, these teenagers also traveled about the city independently, escaping the watchful eyes of supervising adults for extended periods of time. Occasionally, when a favorite Senate Chamber page aged out of that program (in the early 20th century, 12- to 16-year-olds were eligible for the position), they transitioned to the riding page program.4

Much of what we know about the riding page position comes from one of the Senate’s many official records, the secretary of the Senate’s report of expenses, published annually (and later biannually). This report provides historians with a snapshot of the Senate community at a moment in time. The 1896 report, for example, includes all purchases and salaries paid that year, including one oak rocker for the Committee on Claims ($5.50), and a salary of $1,440 paid to S. F. Tappau for service as a messenger to that committee. That same year, the report documents salaries for four riding pages: M. S. Railey, J. A. Thompson, C. A. Loeffler, and Frank Beall. These detailed reports include the names of staff, their titles, and salaries, but do not categorize individuals according to race, ethnicity, or gender. To identify women on Senate staff, historians rely upon other clues, especially “gendered” first names, and turn to other sources, including census records, personal diaries, and newspaper accounts, in hopes of confirming personal details. As the 1896 report suggests, lists of names can be ambiguous when initials, rather than full names, are published. Additionally, feminine names can be difficult to trace through the years. When women marry, they often take their spouse’s surname, complicating efforts to document their full Senate employment record.5

Yet, even with these incomplete records, Senate historians can challenge some long-standing accounts of notable Senate “firsts.” During the summer of 1907, according to the secretary of the Senate’s report, the Senate employed four riding pages: F. Beall , Parker Trent, Albertus Brown, and E. Madeen. A subsequent report reveals that the initial E stands for “Emma.” Madeen may have been the first female page appointment, but no newspapers reported Madeen’s appointment as extraordinary at the time. Unfortunately, no official records provide historians with clues about Madeen’s life in the Senate, on Capitol Hill, or in Washington, DC. How old was she and how did she secure this job? In late December 1907, Helen Taylor replaced Madeen as a riding page. A year later, Taylor was joined by a second female page, Rose Baringer, and others followed. In addition to Madeen, Taylor, and Baringer, Flora White, Henrietta Greeley, Lucy Murphy, Mildred Larrazolo, and Marguerite Frydell served as Senate riding pages between 1907 and 1926.6

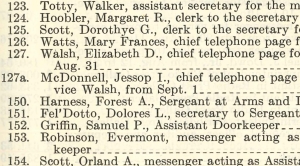

Senators and staff in 1971 may be forgiven for forgetting these female riding pages, who left the Senate 45 years before the Senate reportedly ended the “boys only” page tradition. But even this timeline is more complicated than it seems. From 1951 to 1954, both party cloakrooms employed women as their “chief telephone pages.” Operating out of the private spaces reserved for senators at the rear of the chamber, these women (census records indicate that they were likely adults, rather than girls or teens) answered incoming calls from staff in the Senate office building and provided critical updates about members’ whereabouts and the day’s scheduled floor proceedings and debates. Before technology allowed for the internal broadcasting of floor speeches over so-called “squawk boxes,” the Senate’s telephone pages helped to ensure the institution’s smooth operations and, as a constant presence in the cloakrooms, were likely recognizable. In 1971, when the Senate reportedly ended its “boys only” tradition, at least a dozen senators who voted on that proposal had served in the Senate from 1951 to 1954—when they had likely encountered these female telephone pages.7

Was Emma Madeen the first female page appointment? The answer may be yes—that is, until Senate historians find evidence of an earlier one!

Notes

3. Carl Loeffler unpublished memoir, Senate Historical Office files; John H. White, Jr., Horsecars, Cable Cars and Omnibuses (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1974); Senate Committee on Government Operations, “Special Senate Investigation on Charges and Countercharges Involving: Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens, John G. Adams, H. Struve Hensel and Senator Joe McCarthy, Roy M. Cohn, and Francis P. Carr, Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations,” 83rd Cong., 2nd sess., Part 1, March 16 and April 22, 1954, 35; “Security Minded CIA is so Secure Senator Can’t Get Letter to Director, Page Turned Back at Barricade,” Washington Post, June 11, 1963.