To encourage Americans to learn more about the Constitution, Congress designated September 17—the date in 1787 when delegates to the federal convention signed the Constitution—as Constitution Day.

Throughout the summer of 1787, the framers of the Constitution debated where to place the power to make executive and judicial appointments. Eventually, they settled on the concept of a shared power—the president would make appointments with the “advice and consent” of the Senate. Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution provides that the president "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for.”

The president nominates all federal judges in the judicial branch and specified officers in cabinet-level departments, independent agencies, the military services, the Foreign Service, and uniformed civilian services, as well as U.S. attorneys and U.S. marshals. The vast majority are routinely confirmed, while a small but sometimes highly visible number of nominees fail to receive action or are rejected by the Senate. In its history, the Senate has confirmed 128 Supreme Court nominations and well over 500 cabinet nominations.

The following is a selection of historical documents related to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

John Adams’s Thoughts on Government, 1776

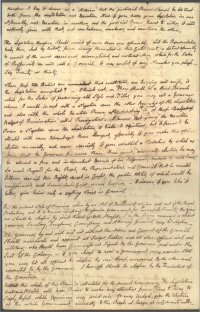

Written in the spring of 1776, John Adams’s Thoughts on Government was first drafted as a letter to North Carolina’s William Hooper, a fellow congressman in the Continental Congress, who had asked Adams for his views on forming a plan of government for North Carolina’s constitution. Adams developed several additional drafts for other colleagues in the following months, and the letter was ultimately published as a pamphlet. Adams’s plan called for three separate branches of government (including a bicameral legislature), which operated within a system of checks and balances, including a shared appointment power. Drawing from similar language in a 1691 Massachusetts’s colonial charter, and referencing a part of the legislative body he called the “Council,” Adams recommended that “The Governor, by and with and not without the Advice and Consent of the Council should nominate and appoint all Judges, Justices, and all other officers civil and military, who should have Commissions signed by the Governor.” Several years later, in 1780, Adams drew from his plan as he helped to write Massachusetts's constitution, which would include the shared appointment power and the phrase “advice and consent.”

In 1787, during the Constitutional Convention, the appointment or nomination clause split the delegates into two factions—those who wanted the executive to have the sole power of appointment, and those who wanted the national legislature, and more specifically the Senate, to have that responsibility. The latter faction followed precedents established by the Articles of Confederation and most of the state constitutions, which granted the legislature the power to make appointments, while the Massachusetts Constitution, with its divided appointment power, provided an alternative model, which was ultimately selected for the U.S. Constitution.

Report of the Grand Committee, September 4, 1787

After debating the appointment clause over the course of several weeks during the Constitutional Convention, the framers eventually settled on the concept of a shared power. Initially, the delegates granted the president the power to appoint the officers of the executive branch and, given that judges’ life-long terms would extend past the authority of any one president, allowed the Senate to appoint members of the judiciary. On September 4, 1787, however, as the proceedings of the convention were nearing conclusion, the Committee of Eleven (also known as the “Grand Committee”)—a special committee consisting of one delegate from each represented state that regularly met to resolve specific disagreements—reported an amended appointment clause. Unanimously adopted on September 7 and based on the Massachusetts constitutional model, which had been recommended earlier during the course of the debates by Massachusetts delegate Nathaniel Gorham, the clause provided that the president shall nominate and, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint the officers of the United States.

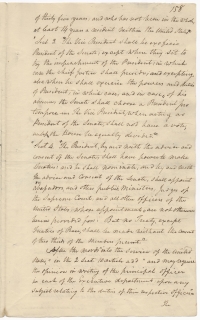

Nomination of Alexander Hamilton to be Secretary of the Treasury, 1789

On September 11, 1789, the new federal government under the Constitution took a large step forward. On that day, President George Washington sent his first cabinet nomination to the Senate for its advice and consent. Minutes later, perhaps even before the messenger returned to the president’s office, senators approved unanimously the appointment of Alexander Hamilton to be secretary of the treasury.

Hamilton’s place in history as the Senate’s first consideration and confirmation of a cabinet nominee is fitting as he had participated in the creation of this shared power. At the Constitutional Convention, and in the subsequent campaign to ensure the Constitution’s ratification, Hamilton was convinced that Senate confirmation of nominees would be a welcome check on the president and supported provisions that divided responsibility for appointing government officials between the president and the Senate. Defending the structure of the appointing power in Federalist 76, Hamilton wrote that the “cooperation of the Senate” in nominations “would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from State prejudice, from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity.”

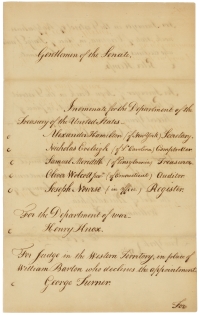

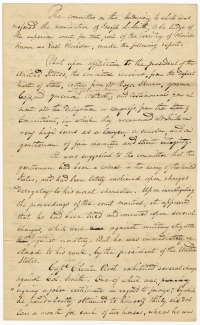

Report of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary Concerning the Nomination of Joseph L. Smith to be Judge of the Superior Court of the Territory of Florida, 1822

The way in which the Senate has exercised its power of advice and consent on nominations has evolved over the course of its history. Before the 1860s, the Senate considered most presidential nominations without referring them to a committee for review or investigation. There were a few exceptions, however, including Joseph L. Smith (nominated by President James Monroe in 1822 to be judge of the Superior Court for the Territory of Florida), who was investigated by the Judiciary Committee, as shown by this report. “It was suggested to the committee that this gentleman had been a colonel in the Army of the United States, and had been lately cashiered upon charges derogatory to his moral character,” the report begins. Subsequently laid out in the report, the committee’s investigation revealed that charges against Smith were refuted by credible witnesses, and he was restored to his rank. “On a full view of all the facts and circumstances,” the report concluded, “the committee could see no objection that ought to operate against the appointment of Col. Smith, and therefore respectfully recommend…that the Senate do advise and consent to the appointment.” Persuaded by the findings of the committee, the full Senate confirmed Smith’s nomination.

Nomination Withdrawal, George H. Williams to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1874

In 1868 the Senate adopted rules to provide for more routine referral of nominations to "appropriate committees," but investigations of judicial nominees typically took place only in cases where the committee received credible allegations of wrongdoing on the part of a nominee. For example, in 1873 the Judiciary Committee, led by Chairman George Edmunds of Vermont, investigated allegations of financial misconduct against Attorney General George H. Williams, who had been nominated to be chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States by President Ulysses S. Grant. After an investigation, the committee informed the president that Williams would likely not be confirmed and Williams asked that his name be withdrawn.

The Senate’s formal order of Williams’s withdrawal begins with, “In Executive Session.” The confirmation of presidential nominations is one of the Senate’s executive (rather than legislative) constitutional duties. This task is therefore performed in executive session, separate from the Senate’s legislative proceedings. Prior to 1929, the Senate rules stipulated that nominations be debated in closed session. These closed executive proceedings were made open on occasion when the Senate voted to ”remove the injunction of secrecy,” and reports of these proceedings were often leaked to the press.

Senator Wilkinson Call to the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on the Nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida, 1890

In its first decade, the Senate established the practice of senatorial courtesy in which senators expected to be consulted on all nominees to federal posts within their states and senators deferred to the wishes of a colleague who objected to an individual nominated to serve in his or her state. If a president insisted on nominating an individual without consultation with or over the objections of a senator, senators merely had to announce in committee or before the full Senate that a nominee was “personally obnoxious” or “personally objectionable” to them without any further explanation. They could depend on the deference of Senate colleagues in rejecting the nominee. While the custom of senatorial courtesy was firmly established by the late 19th century, senatorial objections did not always doom the nomination, especially if a senator was of the opposing party from the president or the Senate majority. In 1890, with Senate Republicans in the majority and Republican Benjamin Harrison in the White House, Judiciary Committee chairman George Edmunds used this form letter to solicit the opinion of Florida Democratic senator Wilkinson Call about the nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida. “I do not consider him to be qualified either mentally or morally for the office of judge,” Call replied. Despite Call’s objection, and the objection of his fellow Florida senator Samuel Pasco (also a Democrat), Swayne’s nomination cleared the Senate.

Blue Slip, Signed by Senator W. Lee O’Daniel, 1943

The Judiciary Committee formalized a version of senatorial courtesy through use of the “blue slip,” a blue sheet of paper on which a senator could register support for or opposition to a judicial nominee to serve in his or her state. The process has varied over the years, with different committee chairs giving varied weight to a negative or non-returned blue slip, but the system has endured, providing home-state senators the opportunity to be heard by the Judiciary Committee. During a nomination debate on the Senate floor in 1960, William Proxmire of Wisconsin called senatorial courtesy “the ultimate senatorial weapon,” a “nuclear warhead intercontinental ballistic missile of Senate nomination action.” While there have been changes to the rules and customs governing Senate advice and consent over the past half century—for example, senators no longer announce in the Senate Chamber that a nominee is “personally obnoxious” to them—individual senators continue to influence the nomination and confirmation process.

Hearings on the Nomination of Sandra Day O’Connor to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1981

During the 20th century, Senate committees hired staff to handle nominations and formalized procedures and practices for scrutinizing nominees. In 1939 Felix Frankfurter became the first nominee to appear before the Judiciary Committee to answer questions in a public hearing, and Dean Acheson became the first nominee for secretary of state to testify in open session before the Foreign Relations Committee 10 years later. By the 1950s, committees began routinely holding public hearings and requiring nominees to appear in person. By the 1990s, Judiciary Committee staff included an investigator who worked on nominations. In 1981 Sandra Day O’Connor of Arizona appeared before the Judiciary Committee as the first woman nominated to the serve on the Supreme Court. O’Connor’s nomination hearing was the first to be televised, and today all committee nomination hearings are broadcast or live-streamed on the Internet.

Today, committees have the option of reporting a nominee to the full Senate with a recommendation to approve ("reported favorably"), with a recommendation to not approve ("reported adversely"), or with no recommendation. Reporting adversely—sometimes because senatorial courtesy was not observed—has become rare. Since the 1970s, committees have on occasion, though still infrequently, voted not to report a nominee to the full Senate, effectively killing the nomination. More frequently, committees do not act on nominations that do not have majority support to move forward.

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution in 1787. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled its constitutional responsibility of advice and consent, playing a role both in the selection and confirmation of nominees.