| 202409 17Constitution Day 2024: The Senate’s Power of Advice and Consent on Nominations

September 17, 2024

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled this important responsibility. This selection of historical documents relates to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

To encourage Americans to learn more about the Constitution, Congress designated September 17—the date in 1787 when delegates to the federal convention signed the Constitution—as Constitution Day.

Throughout the summer of 1787, the framers of the Constitution debated where to place the power to make executive and judicial appointments. Eventually, they settled on the concept of a shared power—the president would make appointments with the “advice and consent” of the Senate. Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution provides that the president "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for.”

The president nominates all federal judges in the judicial branch and specified officers in cabinet-level departments, independent agencies, the military services, the Foreign Service, and uniformed civilian services, as well as U.S. attorneys and U.S. marshals. The vast majority are routinely confirmed, while a small but sometimes highly visible number of nominees fail to receive action or are rejected by the Senate. In its history, the Senate has confirmed 128 Supreme Court nominations and well over 500 cabinet nominations.

The following is a selection of historical documents related to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

John Adams’s Thoughts on Government, 1776

Written in the spring of 1776, John Adams’s Thoughts on Government was first drafted as a letter to North Carolina’s William Hooper, a fellow congressman in the Continental Congress, who had asked Adams for his views on forming a plan of government for North Carolina’s constitution. Adams developed several additional drafts for other colleagues in the following months, and the letter was ultimately published as a pamphlet. Adams’s plan called for three separate branches of government (including a bicameral legislature), which operated within a system of checks and balances, including a shared appointment power. Drawing from similar language in a 1691 Massachusetts’s colonial charter, and referencing a part of the legislative body he called the “Council,” Adams recommended that “The Governor, by and with and not without the Advice and Consent of the Council should nominate and appoint all Judges, Justices, and all other officers civil and military, who should have Commissions signed by the Governor.” Several years later, in 1780, Adams drew from his plan as he helped to write Massachusetts's constitution, which would include the shared appointment power and the phrase “advice and consent.”

In 1787, during the Constitutional Convention, the appointment or nomination clause split the delegates into two factions—those who wanted the executive to have the sole power of appointment, and those who wanted the national legislature, and more specifically the Senate, to have that responsibility. The latter faction followed precedents established by the Articles of Confederation and most of the state constitutions, which granted the legislature the power to make appointments, while the Massachusetts Constitution, with its divided appointment power, provided an alternative model, which was ultimately selected for the U.S. Constitution.

Report of the Grand Committee, September 4, 1787

After debating the appointment clause over the course of several weeks during the Constitutional Convention, the framers eventually settled on the concept of a shared power. Initially, the delegates granted the president the power to appoint the officers of the executive branch and, given that judges’ life-long terms would extend past the authority of any one president, allowed the Senate to appoint members of the judiciary. On September 4, 1787, however, as the proceedings of the convention were nearing conclusion, the Committee of Eleven (also known as the “Grand Committee”)—a special committee consisting of one delegate from each represented state that regularly met to resolve specific disagreements—reported an amended appointment clause. Unanimously adopted on September 7 and based on the Massachusetts constitutional model, which had been recommended earlier during the course of the debates by Massachusetts delegate Nathaniel Gorham, the clause provided that the president shall nominate and, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint the officers of the United States.

Nomination of Alexander Hamilton to be Secretary of the Treasury, 1789

On September 11, 1789, the new federal government under the Constitution took a large step forward. On that day, President George Washington sent his first cabinet nomination to the Senate for its advice and consent. Minutes later, perhaps even before the messenger returned to the president’s office, senators approved unanimously the appointment of Alexander Hamilton to be secretary of the treasury.

Hamilton’s place in history as the Senate’s first consideration and confirmation of a cabinet nominee is fitting as he had participated in the creation of this shared power. At the Constitutional Convention, and in the subsequent campaign to ensure the Constitution’s ratification, Hamilton was convinced that Senate confirmation of nominees would be a welcome check on the president and supported provisions that divided responsibility for appointing government officials between the president and the Senate. Defending the structure of the appointing power in Federalist 76, Hamilton wrote that the “cooperation of the Senate” in nominations “would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from State prejudice, from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity.”

Report of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary Concerning the Nomination of Joseph L. Smith to be Judge of the Superior Court of the Territory of Florida, 1822

The way in which the Senate has exercised its power of advice and consent on nominations has evolved over the course of its history. Before the 1860s, the Senate considered most presidential nominations without referring them to a committee for review or investigation. There were a few exceptions, however, including Joseph L. Smith (nominated by President James Monroe in 1822 to be judge of the Superior Court for the Territory of Florida), who was investigated by the Judiciary Committee, as shown by this report. “It was suggested to the committee that this gentleman had been a colonel in the Army of the United States, and had been lately cashiered upon charges derogatory to his moral character,” the report begins. Subsequently laid out in the report, the committee’s investigation revealed that charges against Smith were refuted by credible witnesses, and he was restored to his rank. “On a full view of all the facts and circumstances,” the report concluded, “the committee could see no objection that ought to operate against the appointment of Col. Smith, and therefore respectfully recommend…that the Senate do advise and consent to the appointment.” Persuaded by the findings of the committee, the full Senate confirmed Smith’s nomination.

Nomination Withdrawal, George H. Williams to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1874

In 1868 the Senate adopted rules to provide for more routine referral of nominations to "appropriate committees," but investigations of judicial nominees typically took place only in cases where the committee received credible allegations of wrongdoing on the part of a nominee. For example, in 1873 the Judiciary Committee, led by Chairman George Edmunds of Vermont, investigated allegations of financial misconduct against Attorney General George H. Williams, who had been nominated to be chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States by President Ulysses S. Grant. After an investigation, the committee informed the president that Williams would likely not be confirmed and Williams asked that his name be withdrawn.

The Senate’s formal order of Williams’s withdrawal begins with, “In Executive Session.” The confirmation of presidential nominations is one of the Senate’s executive (rather than legislative) constitutional duties. This task is therefore performed in executive session, separate from the Senate’s legislative proceedings. Prior to 1929, the Senate rules stipulated that nominations be debated in closed session. These closed executive proceedings were made open on occasion when the Senate voted to ”remove the injunction of secrecy,” and reports of these proceedings were often leaked to the press.

Senator Wilkinson Call to the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on the Nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida, 1890

In its first decade, the Senate established the practice of senatorial courtesy in which senators expected to be consulted on all nominees to federal posts within their states and senators deferred to the wishes of a colleague who objected to an individual nominated to serve in his or her state. If a president insisted on nominating an individual without consultation with or over the objections of a senator, senators merely had to announce in committee or before the full Senate that a nominee was “personally obnoxious” or “personally objectionable” to them without any further explanation. They could depend on the deference of Senate colleagues in rejecting the nominee. While the custom of senatorial courtesy was firmly established by the late 19th century, senatorial objections did not always doom the nomination, especially if a senator was of the opposing party from the president or the Senate majority. In 1890, with Senate Republicans in the majority and Republican Benjamin Harrison in the White House, Judiciary Committee chairman George Edmunds used this form letter to solicit the opinion of Florida Democratic senator Wilkinson Call about the nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida. “I do not consider him to be qualified either mentally or morally for the office of judge,” Call replied. Despite Call’s objection, and the objection of his fellow Florida senator Samuel Pasco (also a Democrat), Swayne’s nomination cleared the Senate.

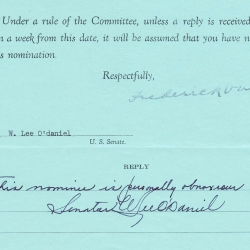

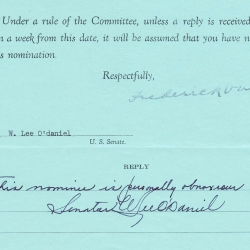

Blue Slip, Signed by Senator W. Lee O’Daniel, 1943

The Judiciary Committee formalized a version of senatorial courtesy through use of the “blue slip,” a blue sheet of paper on which a senator could register support for or opposition to a judicial nominee to serve in his or her state. The process has varied over the years, with different committee chairs giving varied weight to a negative or non-returned blue slip, but the system has endured, providing home-state senators the opportunity to be heard by the Judiciary Committee. During a nomination debate on the Senate floor in 1960, William Proxmire of Wisconsin called senatorial courtesy “the ultimate senatorial weapon,” a “nuclear warhead intercontinental ballistic missile of Senate nomination action.” While there have been changes to the rules and customs governing Senate advice and consent over the past half century—for example, senators no longer announce in the Senate Chamber that a nominee is “personally obnoxious” to them—individual senators continue to influence the nomination and confirmation process.

Hearings on the Nomination of Sandra Day O’Connor to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1981

During the 20th century, Senate committees hired staff to handle nominations and formalized procedures and practices for scrutinizing nominees. In 1939 Felix Frankfurter became the first nominee to appear before the Judiciary Committee to answer questions in a public hearing, and Dean Acheson became the first nominee for secretary of state to testify in open session before the Foreign Relations Committee 10 years later. By the 1950s, committees began routinely holding public hearings and requiring nominees to appear in person. By the 1990s, Judiciary Committee staff included an investigator who worked on nominations. In 1981 Sandra Day O’Connor of Arizona appeared before the Judiciary Committee as the first woman nominated to the serve on the Supreme Court. O’Connor’s nomination hearing was the first to be televised, and today all committee nomination hearings are broadcast or live-streamed on the Internet.

Today, committees have the option of reporting a nominee to the full Senate with a recommendation to approve ("reported favorably"), with a recommendation to not approve ("reported adversely"), or with no recommendation. Reporting adversely—sometimes because senatorial courtesy was not observed—has become rare. Since the 1970s, committees have on occasion, though still infrequently, voted not to report a nominee to the full Senate, effectively killing the nomination. More frequently, committees do not act on nominations that do not have majority support to move forward.

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution in 1787. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled its constitutional responsibility of advice and consent, playing a role both in the selection and confirmation of nominees.

|

| 202207 05Origins of Senatorial Courtesy

July 05, 2022

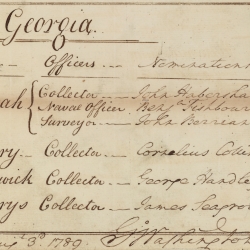

On August 5, 1789, the Senate rejected for the first time a presidential nominee. At the urging of Georgia senator James Gunn, the Senate failed to confirm Benjamin Fishbourn, President George Washington’s nominee to serve as federal naval officer for the Port of Savannah. The Senate’s rejection of Fishbourn has been regarded as the first assertion of “senatorial courtesy.”

On August 5, 1789, the Senate rejected for the first time a presidential nominee. At the urging of Georgia senator James Gunn, the Senate failed to confirm Benjamin Fishbourn, President George Washington’s nominee to serve as federal naval officer for the Port of Savannah. The Senate’s rejection of Fishbourn has been regarded as the first assertion of “senatorial courtesy,” the practice whereby senators defer to the wishes of a colleague who objects to an individual nominated to serve in his or her state. Senatorial courtesy also has been interpreted to mean that a president should consult with senators of his or her party when nominating individuals to serve in positions in their home states. Such a practice was not envisioned by the framers. In fact, in The Federalist, No. 66, Alexander Hamilton wrote: “There will, of course, be no exertion of choice [in executive appointments] on the part of Senators. They can only ratify or reject the choice of the President.”1

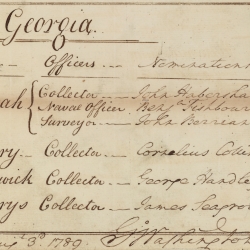

Like other office seekers, Fishbourn had written to Washington in hopes of securing a federal appointment in the new government. Fishbourn had served in the Georgia legislature and had been appointed earlier that year as state naval officer of Savannah by the state’s governor. He hoped to fill the same role for the federal government. Washington had informed Fishbourn that he would assume the presidency “free from engagements of every kind and nature whatsoever,” and would make appointments only with “justice” and “the public good” in mind. Fishbourn benefitted, however, from the support of General Anthony Wayne, under whom he had served as aide-de-camp during the Revolutionary War. Wayne had a close bond with Washington and had recommended Fishbourn for a position in the government. As a result, Fishbourn’s name was added to President Washington’s long list of nominees to serve as customs collectors, naval officers, and land surveyors throughout the country that was presented to the Senate on August 3, 1789. The Senate confirmed most of the nominees on the list the next day. Two other nominees from Georgia were confirmed on August 5, but the Senate, at the urging of Senator Gunn, rejected Fishbourn.2

Why did Senator Gunn object to Fishbourn? The drama surrounding the nomination can be traced back to a duel challenge and personal rivalries. Affairs of honor, in which men in the public eye were willing to exchange gunfire and risk death in defense of their reputations, were an important element of politics in the early American republic. In 1785 James Gunn, while serving as an army captain, feuded with Major General Nathanael Greene over a rather arcane military policy. At some point during the Revolutionary War, James Gunn’s horse was killed in battle. He was able to select a government-procured horse to use during the remainder of the war, as was custom. The problem arose when Gunn traded the horse, which was considered to be quite valuable, for two other horses and an enslaved individual. General Greene objected to the transaction, not for the atrocity that an enslaved person was considered property equivalent to a horse, but because Gunn had dispensed with government property as if it was his personal property. Greene called for a military court of inquiry to investigate. The court ruled that Gunn was justified in trading the horse, but Greene was not satisfied. He ordered Gunn to return the horse and referred the matter to the Continental Congress. Congress adopted resolutions supporting Greene’s actions and ordered Gunn to replace the horse with “another equally good.”3

After the war, both Gunn and Greene settled in Georgia. Gunn, still smarting from what he saw as Greene’s attack on his character, challenged Greene to a duel. Greene refused the challenge, claiming that a commanding officer could not be accountable to a subordinate for his actions while in command. Gunn reportedly declared that “he would attack [Greene] wherever he met him” and began to carry pistols in the event of an encounter. The confrontation never occurred, and Greene received support from Washington himself, who assured him that his “honor and reputation will stand” for refusing to accept Gunn’s challenge.4

What does all of this have to do with Fishbourn and senatorial courtesy? Fishbourn had publicly sided with Greene during the dispute, and Gunn never forgot that. When asked by another senator to explain his reasons for objecting to Fishbourn, Gunn responded simply with “personal invective and abuse.” This was enough to sway other senators to vote down the nomination.5

Angry about the rejection of his nominee, Washington wrote in a message to the Senate, “Permit me to submit to your consideration whether on occasions where the propriety of Nominations appear questionable to you, it would not be expedient to communicate that circumstance to me, and thereby avail yourselves of the information which led me to make them, and which I would with pleasure lay before you.” Washington, according to one source, even went to the Chamber to ask the Senate’s reasons for the rejection, to which Gunn informed him that the Senate owed him no explanation.6

Fishbourn was stung by the rejection. His supporters attempted to undo the damage to his reputation. Anthony Wayne wrote to Washington to assure him that the “unmerited and wanton attack upon [Fishbourn's] Character by Mr. Gunn” was groundless and that he would never have recommended Fishbourn for the position if the charges were true. Wayne published a defense of Fishbourn signed by notable men from Savannah.7

A month later, Fishbourn sent a letter to Washington in hopes of repairing his reputation after such a public embarrassment. He asked the president to write him indicating that he held no prejudices against him based on “representations having been made against me in the Senate.” As he left Georgia and public life, he hoped “I may have it to say I have the sanction as well as the good wishes of his Excellency the President of the United States.” Fishbourn was probably disappointed to receive a reply only from an aide to Washington, stating “I am directed by him to inform you that when he nominated you for Naval Officer of the Port of Savannah he was ignorant of any charge existing against you—and, not having, since that time, had any other exibit (sic) of the facts which were alledged (sic) in the Senate . . . he does not consider himself competent to give any opinion on the subject.”8

Senator James Gunn’s objection to Fishbourn for what he saw as an affront to his public honor—even if Fishbourn was but a minor player in the affair—established an enduring precedent in the Senate. Despite periodic efforts by presidents to push back on senators’ attempts to control executive appointments, the custom of senatorial courtesy became firmly established by the late 19th century. In 1906, two years prior to his run for president, William Howard Taft observed that presidents were “naturally quite dependent on . . . advice and recommendation” of senators, such that “the appointing power is in effect in their hands subject only to a veto by the President.” When considering a nomination in executive session—held behind closed doors until 1929—senators merely had to rise and announce that a nominee was “personally obnoxious” or “personally objectionable” to them, without any further explanation. They could depend on the deference of Senate colleagues in rejecting the nominee. The Senate Judiciary Committee formalized a version of senatorial courtesy through use of the “blue slip,” a blue sheet of paper on which a senator could register support for or opposition to a judicial nominee to serve in his or her state. In 1960 William Proxmire of Wisconsin called senatorial courtesy “the ultimate senatorial weapon,” a “nuclear warhead intercontinental ballistic missile of Senate nomination action.” While there have been changes to the rules and customs governing Senate advice and consent over the past half century—for example, senators no longer announce on the floor that a nominee is “personally obnoxious” to them—individual senators continue to exert a great deal of power over the nomination and confirmation process.9

Notes

1. Robert C. Byrd, The Senate, 1789-1989: Addresses on the History of the United States Senate, vol. 2, ed. Wendy Wolff, S. Doc. 100-20, 100th Cong., 1st sess. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1991), 31; Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 66, quoted in George H. Haynes, The Senate of the United States: Its History and Practice (Cambridge: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1938), 2:736.

2. Mitchel A. Sollenberger, “Georgia’s Influence on the U. S. Senate: A Reassessment of the Rejection of Benjamin Fishbourn and the Origin of Senatorial Courtesy,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 93, no. 2 (2009): 182–90; “From George Washington to Benjamin Fishbourn, 23 December 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0148. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 24 September 1788 – 31 March 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987), 198–200.]; “To George Washington from Anthony Wayne, 10 May 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-02-02-0189. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 2, 1 April 1789 – 15 June 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987), 261–64.]

3. Joanne B. Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the Early Republic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); George R. Lamplugh, “The Importance of Being Truculent: James Gunn, the Chatham Militia, and Georgia Politics, 1782–1789,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 80, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 228–29; Sollenberger, “Georgia’s Influence,” 185–87.

4. Sollenberger, “Georgia’s Influence,” 187; Lamplugh, “Importance of Being Truculent,” 232.

5. Fergus M. Bordewich, The First Federal Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2016), 132; Lamplugh, “Importance of Being Truculent,” 240–43.

6. “From George Washington to Benjamin Fishbourn, 23 December 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0148. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 198–200.] Washington’s visit to the Senate was recounted years later by the son of Washington aide Tobias Lear. Notably, William Maclay was absent on that day, but he committed to his diary the comments of a fellow senator about Washington’s intemperate response to the rejection, though it is not clear if that occurred in person in the Senate chamber. Kenneth R. Bowling and Helen E. Veit, eds., Diary of William Maclay and Other Notes on Senate Debates, vol. 9 of Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, eds. Linda Grant De Pauw et al. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 121.

7. “To George Washington from Anthony Wayne, 30 August 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-03-02-0330. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 3, 15 June 1789–5 September 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 569–70.]

8. “To George Washington from Benjamin Fishbourn, 25 September 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-04-02-0054 [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 4, 8 September 1789 – 15 January 1790, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), 81–83; fn1.] This was quite a change in tone from December 1788, when Washington wrote in a letter to Fishbourn: “For you may rest assured, Sir, that, while I feel a sincere pleasure in hearing of the prosperity of my army acquaintances in general, the satisfaction is of a nature still more interesting, when the success has attended an officer with whose services I was more particularly acquainted.”; “From George Washington to Benjamin Fishbourn, 23 December 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed June 22, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0148 [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 198–200.]

9. William Howard Taft, Four Aspects of Civic Duty (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 98–99, quoted in Haynes, Senate of the United States, 1:736; Congressional Record, 86th Cong., 2nd Sess., April 19, 1960, 8159; Michael J. Gerhardt, The Federal Appointments Process (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), 143–53.

|