| 202409 17Constitution Day 2024: The Senate’s Power of Advice and Consent on Nominations

September 17, 2024

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled this important responsibility. This selection of historical documents relates to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

To encourage Americans to learn more about the Constitution, Congress designated September 17—the date in 1787 when delegates to the federal convention signed the Constitution—as Constitution Day.

Throughout the summer of 1787, the framers of the Constitution debated where to place the power to make executive and judicial appointments. Eventually, they settled on the concept of a shared power—the president would make appointments with the “advice and consent” of the Senate. Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution provides that the president "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for.”

The president nominates all federal judges in the judicial branch and specified officers in cabinet-level departments, independent agencies, the military services, the Foreign Service, and uniformed civilian services, as well as U.S. attorneys and U.S. marshals. The vast majority are routinely confirmed, while a small but sometimes highly visible number of nominees fail to receive action or are rejected by the Senate. In its history, the Senate has confirmed 128 Supreme Court nominations and well over 500 cabinet nominations.

The following is a selection of historical documents related to the establishment and exercise of the Senate’s power of advice and consent on nominations.

John Adams’s Thoughts on Government, 1776

Written in the spring of 1776, John Adams’s Thoughts on Government was first drafted as a letter to North Carolina’s William Hooper, a fellow congressman in the Continental Congress, who had asked Adams for his views on forming a plan of government for North Carolina’s constitution. Adams developed several additional drafts for other colleagues in the following months, and the letter was ultimately published as a pamphlet. Adams’s plan called for three separate branches of government (including a bicameral legislature), which operated within a system of checks and balances, including a shared appointment power. Drawing from similar language in a 1691 Massachusetts’s colonial charter, and referencing a part of the legislative body he called the “Council,” Adams recommended that “The Governor, by and with and not without the Advice and Consent of the Council should nominate and appoint all Judges, Justices, and all other officers civil and military, who should have Commissions signed by the Governor.” Several years later, in 1780, Adams drew from his plan as he helped to write Massachusetts's constitution, which would include the shared appointment power and the phrase “advice and consent.”

In 1787, during the Constitutional Convention, the appointment or nomination clause split the delegates into two factions—those who wanted the executive to have the sole power of appointment, and those who wanted the national legislature, and more specifically the Senate, to have that responsibility. The latter faction followed precedents established by the Articles of Confederation and most of the state constitutions, which granted the legislature the power to make appointments, while the Massachusetts Constitution, with its divided appointment power, provided an alternative model, which was ultimately selected for the U.S. Constitution.

Report of the Grand Committee, September 4, 1787

After debating the appointment clause over the course of several weeks during the Constitutional Convention, the framers eventually settled on the concept of a shared power. Initially, the delegates granted the president the power to appoint the officers of the executive branch and, given that judges’ life-long terms would extend past the authority of any one president, allowed the Senate to appoint members of the judiciary. On September 4, 1787, however, as the proceedings of the convention were nearing conclusion, the Committee of Eleven (also known as the “Grand Committee”)—a special committee consisting of one delegate from each represented state that regularly met to resolve specific disagreements—reported an amended appointment clause. Unanimously adopted on September 7 and based on the Massachusetts constitutional model, which had been recommended earlier during the course of the debates by Massachusetts delegate Nathaniel Gorham, the clause provided that the president shall nominate and, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint the officers of the United States.

Nomination of Alexander Hamilton to be Secretary of the Treasury, 1789

On September 11, 1789, the new federal government under the Constitution took a large step forward. On that day, President George Washington sent his first cabinet nomination to the Senate for its advice and consent. Minutes later, perhaps even before the messenger returned to the president’s office, senators approved unanimously the appointment of Alexander Hamilton to be secretary of the treasury.

Hamilton’s place in history as the Senate’s first consideration and confirmation of a cabinet nominee is fitting as he had participated in the creation of this shared power. At the Constitutional Convention, and in the subsequent campaign to ensure the Constitution’s ratification, Hamilton was convinced that Senate confirmation of nominees would be a welcome check on the president and supported provisions that divided responsibility for appointing government officials between the president and the Senate. Defending the structure of the appointing power in Federalist 76, Hamilton wrote that the “cooperation of the Senate” in nominations “would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from State prejudice, from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity.”

Report of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary Concerning the Nomination of Joseph L. Smith to be Judge of the Superior Court of the Territory of Florida, 1822

The way in which the Senate has exercised its power of advice and consent on nominations has evolved over the course of its history. Before the 1860s, the Senate considered most presidential nominations without referring them to a committee for review or investigation. There were a few exceptions, however, including Joseph L. Smith (nominated by President James Monroe in 1822 to be judge of the Superior Court for the Territory of Florida), who was investigated by the Judiciary Committee, as shown by this report. “It was suggested to the committee that this gentleman had been a colonel in the Army of the United States, and had been lately cashiered upon charges derogatory to his moral character,” the report begins. Subsequently laid out in the report, the committee’s investigation revealed that charges against Smith were refuted by credible witnesses, and he was restored to his rank. “On a full view of all the facts and circumstances,” the report concluded, “the committee could see no objection that ought to operate against the appointment of Col. Smith, and therefore respectfully recommend…that the Senate do advise and consent to the appointment.” Persuaded by the findings of the committee, the full Senate confirmed Smith’s nomination.

Nomination Withdrawal, George H. Williams to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1874

In 1868 the Senate adopted rules to provide for more routine referral of nominations to "appropriate committees," but investigations of judicial nominees typically took place only in cases where the committee received credible allegations of wrongdoing on the part of a nominee. For example, in 1873 the Judiciary Committee, led by Chairman George Edmunds of Vermont, investigated allegations of financial misconduct against Attorney General George H. Williams, who had been nominated to be chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States by President Ulysses S. Grant. After an investigation, the committee informed the president that Williams would likely not be confirmed and Williams asked that his name be withdrawn.

The Senate’s formal order of Williams’s withdrawal begins with, “In Executive Session.” The confirmation of presidential nominations is one of the Senate’s executive (rather than legislative) constitutional duties. This task is therefore performed in executive session, separate from the Senate’s legislative proceedings. Prior to 1929, the Senate rules stipulated that nominations be debated in closed session. These closed executive proceedings were made open on occasion when the Senate voted to ”remove the injunction of secrecy,” and reports of these proceedings were often leaked to the press.

Senator Wilkinson Call to the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on the Nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida, 1890

In its first decade, the Senate established the practice of senatorial courtesy in which senators expected to be consulted on all nominees to federal posts within their states and senators deferred to the wishes of a colleague who objected to an individual nominated to serve in his or her state. If a president insisted on nominating an individual without consultation with or over the objections of a senator, senators merely had to announce in committee or before the full Senate that a nominee was “personally obnoxious” or “personally objectionable” to them without any further explanation. They could depend on the deference of Senate colleagues in rejecting the nominee. While the custom of senatorial courtesy was firmly established by the late 19th century, senatorial objections did not always doom the nomination, especially if a senator was of the opposing party from the president or the Senate majority. In 1890, with Senate Republicans in the majority and Republican Benjamin Harrison in the White House, Judiciary Committee chairman George Edmunds used this form letter to solicit the opinion of Florida Democratic senator Wilkinson Call about the nomination of Charles Swayne to be U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Florida. “I do not consider him to be qualified either mentally or morally for the office of judge,” Call replied. Despite Call’s objection, and the objection of his fellow Florida senator Samuel Pasco (also a Democrat), Swayne’s nomination cleared the Senate.

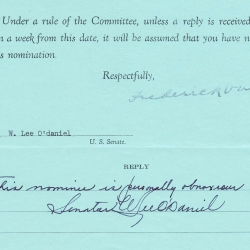

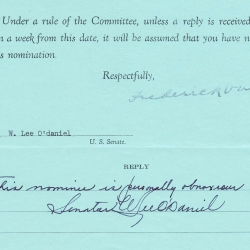

Blue Slip, Signed by Senator W. Lee O’Daniel, 1943

The Judiciary Committee formalized a version of senatorial courtesy through use of the “blue slip,” a blue sheet of paper on which a senator could register support for or opposition to a judicial nominee to serve in his or her state. The process has varied over the years, with different committee chairs giving varied weight to a negative or non-returned blue slip, but the system has endured, providing home-state senators the opportunity to be heard by the Judiciary Committee. During a nomination debate on the Senate floor in 1960, William Proxmire of Wisconsin called senatorial courtesy “the ultimate senatorial weapon,” a “nuclear warhead intercontinental ballistic missile of Senate nomination action.” While there have been changes to the rules and customs governing Senate advice and consent over the past half century—for example, senators no longer announce in the Senate Chamber that a nominee is “personally obnoxious” to them—individual senators continue to influence the nomination and confirmation process.

Hearings on the Nomination of Sandra Day O’Connor to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1981

During the 20th century, Senate committees hired staff to handle nominations and formalized procedures and practices for scrutinizing nominees. In 1939 Felix Frankfurter became the first nominee to appear before the Judiciary Committee to answer questions in a public hearing, and Dean Acheson became the first nominee for secretary of state to testify in open session before the Foreign Relations Committee 10 years later. By the 1950s, committees began routinely holding public hearings and requiring nominees to appear in person. By the 1990s, Judiciary Committee staff included an investigator who worked on nominations. In 1981 Sandra Day O’Connor of Arizona appeared before the Judiciary Committee as the first woman nominated to the serve on the Supreme Court. O’Connor’s nomination hearing was the first to be televised, and today all committee nomination hearings are broadcast or live-streamed on the Internet.

Today, committees have the option of reporting a nominee to the full Senate with a recommendation to approve ("reported favorably"), with a recommendation to not approve ("reported adversely"), or with no recommendation. Reporting adversely—sometimes because senatorial courtesy was not observed—has become rare. Since the 1970s, committees have on occasion, though still infrequently, voted not to report a nominee to the full Senate, effectively killing the nomination. More frequently, committees do not act on nominations that do not have majority support to move forward.

Through its power of advice and consent on nominations, the Senate serves a pivotal role in the complex system of check and balances established by the framers of the Constitution in 1787. While the way in which the Senate has exercised that power has evolved over the course of its history, it has consistently fulfilled its constitutional responsibility of advice and consent, playing a role both in the selection and confirmation of nominees.

|

| 202105 03Senate Progressives vs. the Federal Courts

May 03, 2021

In the early 20th century, a group of progressive senators from midwestern and western states arrived in Washington committed to expanding the role of the federal government to address the economic and social challenges of industrialization. To accomplish these goals, they had to tackle another challenge—the power of the federal judiciary.

In the early 20th century, a group of progressive senators from midwestern and western states arrived in Washington committed to expanding the role of the federal government to address the economic and social challenges of industrialization. To accomplish these goals, they had to tackle another challenge—the power of the federal judiciary. Senate progressives like Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, William Borah of Idaho, George Norris of Nebraska, and Robert Owen of Oklahoma viewed the federal courts as a growing obstacle to their reformist agenda and worked to limit their power.1

Their top target was the United States Supreme Court. Under a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and its guarantee of “due process of law,” the Supreme Court, beginning in the 1890s, used judicial review to an unprecedented extent in order to declare state laws unconstitutional. The Court weakened the power of state governments to regulate the rates of railroads and other public utilities. It struck down state laws regulating the wages and hours of workers, most famously in the 1905 case Lochner v. New York, in which the Court ruled that a law limiting the number of hours a baker could work was an infringement on a worker’s “liberty of contract.”2

The Supreme Court struck down federal laws as well. When Congress passed a law in 1916 banning child labor—a bill co-sponsored in the Senate by Robert Owen—the Court declared it unconstitutional two years later in the case of Hammer v. Dagenhart. In 1923 the Court also invalidated a federal law establishing a minimum wage for women in the District of Columbia.3

The progressives also had concerns about the actions of lower courts. When corporations challenged state regulations, federal district judges issued injunctions barring state officials from enforcing the laws. Federal judges handed down injunctions to stop labor unions from engaging in boycotts and certain strike tactics. District judges ordered the arrest of those who violated their injunctions for contempt of court. Labor leaders and progressive politicians denounced “government by injunction” and what they saw as an abuse of judicial power.4

Progressives, including those in the Senate, responded with proposals to make federal judges more accountable to the people. In 1911 Robert Owen proposed that a majority of both houses of Congress have the power to recall a judge and remove him from office. “The Federal judiciary has become the bulwark of privilege,” he stated in a 1911 speech, “and ought to be made immediately subject to legislative recall by the representatives of the people.” In 1918, after the Court struck down the federal ban on child labor in a 5-4 decision, Owen rejected the notion that a single judge could be the determining factor in nullifying “the matured public opinion of the country as expressed by Congress.” He introduced a new bill to reinstate the ban and included a provision to ban the Court from striking it down.5

Owen was not alone in his attacks on the Court. Similarly, William Borah saw closely divided decisions as “a matter of deep regret.” He introduced legislation in 1923 that would have required the support of at least seven of the nine justices on the Court to invalidate a statute. When the Court once again struck down a federal anti–child labor law in 1922, Robert La Follette condemned these “judicial usurpations” and called for a constitutional amendment to allow Congress to override the Supreme Court by simply re-passing any laws declared unconstitutional.6

Progressives made up a small coalition within the Senate in the 1920s, and while they did not have enough congressional support to pass their court proposals, they asserted what power they could. Progressive Republicans like Senators La Follette, Borah, and Hiram Johnson of California represented a small portion of the Senate’s Republican caucus and were often at odds with the caucus’s more powerful Old Guard members. This division became apparent by 1921 in the relationship between Senate progressives and Chief Justice William Howard Taft.

La Follette had already battled with Taft while he was president and had helped to defeat Taft’s campaign for a second term in 1912. Subsequently, La Follette, Borah, and Johnson were three of the four senators to vote against Taft’s appointment to the Court in 1921. Along with Progressive Democrats like Owen and Thomas Walsh of Montana, they continued to frustrate Taft during his tenure as chief justice.

Taft, who had served as a federal circuit judge in the 1890s and later defended the power of the courts as president of the American Bar Association in 1914, had his own goals for the federal judiciary. In his view, the problem with the courts was not judicial review or injunctions—he praised both as indispensable tools to protect property rights from political majorities. Rather, he believed that the federal courts needed to become more efficient in handling their rising caseloads, and this meant giving the chief justice “executive authority” over the lower courts. In 1922 Taft drafted a bill with Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty, introduced in the Senate by Taft ally Albert Cummins of Iowa, to create a conference of federal circuit judges headed by the chief justice that would gather caseload information from the lower courts. The legislation also proposed appointing a new group of at-large judges and giving the conference the power to send them to districts across the country with backlogs of cases.7

Progressive Republicans, along with many Democrats, were in no rush to strengthen the power of the chief justice over the judiciary, especially not that of the conservative Taft. George Norris even opposed the idea of judges gathering in Washington to be influenced by the chief justice. Norris used his time during the Senate debate over Taft’s bill to call for abolishing the lower federal courts altogether and returning jurisdiction to the state courts.8

The progressive Republicans joined forces with southern Democrats to oppose Taft’s plan. Senators jealously protected the influence they had in presidential nominations of district and circuit judges who would preside in their states. Southern senators argued that the chief justice would have power to send northern “carpet-bagging” judges to southern courts, possibly to enforce a proposed federal anti-lynching law under consideration in 1922. Tennessee Democrat John Shields—who resented Taft’s role in drafting the legislation in the first place—argued that the creation of at-large judges and the power to assign them to any district represented an infringement on the independence of district courts. Thaddeus Caraway of Arkansas objected to “giving to the Chief Justice the power to send out a horde of judges all over this country to designated places, concentrating in his power the whole judiciary system.” In the end, Taft got his Conference of Senior Circuit Judges but not the power to reassign what he called a “flying squadron” of judges.9

Taft chafed at Senate opposition, especially from those opponents who were members of his own party. He bemoaned that “being attacked by progressives” was “the penalty one has to pay for trying to reform matters.” Taft went so far as to lobby Republican Leader Henry Cabot Lodge to get senators more sympathetic to his proposals onto the Senate Judiciary Committee to counter Borah and Norris. He wrote to a fellow judge that the “yahoos of the West . . . were Republicans in getting on committees but not Republicans after they have succeeded.” Lodge, while sympathetic to the challenges posed by insurgents within the Republican ranks, politely rebuffed Taft.10

Senate progressives continued their efforts to curb the courts into the 1920s and even after Taft left the Court in 1930, winning victories with anti-injunction laws and defeating or delaying other elements of Taft’s plans. Norris was able to exert particular influence when he became chairman of the Judiciary Committee in 1926. Progressives also succeeded in defeating the nomination of Judge John J. Parker to the Supreme Court in 1930 after raising objections to his anti-labor rulings and to his opposition to African American voting rights. Such victories were short-lived, however, as the flurry of legislation passed during the Great Depression ensured that the battle between Congress and the courts would continue for years to come.

Notes

1. William G. Ross, A Muted Fury: Populists, Progressives, and Labor Unions Confront the Courts, 1890–1937 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994).

2. Paul Kens, The Lochner Era: Economic Regulation on Trial (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998).

3. Adkins v. Children’s Hospital, 261 U.S. 525 (1923).

4. William Forbath, Law and the Shaping of the American Labor Movement (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991).

5. Judicial Recall, Address by Senator Robert L. Owen, S. Doc. 62-249, 62nd Cong., 2nd sess., January 11, 1912; Congressional Record, 65th Cong., 2nd sess., June 6, 1918, 7432–33.

6. William E. Borah, “Five to Four Decisions as Menace to Respect for Supreme Court,” New York Times, February 18, 1923, 21; Report of the Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Convention of the American Federation of Labor (Washington, D.C.: Law Reporter, 1922), 234–43; Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co., 259 U.S. 20 (1922).

7. William Howard Taft, “The Selection and Tenure of Judges,” Report of the 36th Annual Meeting of the American Bar Association (1913), 420–26; Daniel S. Holt, ed., Debates on the Federal Judiciary: A Documentary History, Volume 2, 1875–1939 (Washington, D.C.: Federal Judicial Center, 2013), 180–96.

8. Congressional Record, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., April 6, 1922, 5107–14.

9. Congressional Record, 67th Cong., 2nd sess., March 31, 1922, 4848–49, 4855–65,; William Howard Taft, “Possible and Needed Reforms in Administration of Justice in Federal Courts,” American Bar Association Journal 8, no. 10 (October 1922): 601.

10. Taft to Hiscock, April 12, 1922, Taft to Lodge, January 17, 1922, Taft to Judge Baker, January 22, 1922, Taft to Robert Taft, April 5, 1924, Lodge to Taft, January 18, 1922, William Howard Taft Papers, Series 3: General Correspondence, 1877–1941, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

|